1

Practice Manual: Labor-Based Deferred Action

1

March 24, 2023

I. Introduction _____________________________________________________________ 2

II. Applying for Labor-Based Deferred Action ____________________________________ 3

A. What is Deferred Action? _______________________________________________________ 3

B. Who is Eligible for Labor-Based Deferred Action? __________________________________ 5

1. Identifying and Reporting Labor and Employment Law Violations ____________________________ 7

2. Obtaining a Labor or Employment Agency Statement of Interest _____________________________ 10

C. Screening & Counseling for Labor-Based Deferred Action __________________________ 13

1. Immigration Screening Interview ______________________________________________________ 13

2. Understanding Immigration and Criminal History—FOIAs & Other Record Requests ____________ 15

3. Counseling _______________________________________________________________________ 17

D. Preparing a Labor-Based Deferred Action Application _____________________________ 20

1. Contents of Deferred Action and Employment Authorization Packet __________________________ 21

2. Jurisdiction Over the Deferred Action Application—USCIS vs. ICE __________________________ 26

3. Timing & Expedite Requests _________________________________________________________ 27

4. Follow-Up & Troubleshooting ________________________________________________________ 28

5. Responding to Requests for Evidence (RFE) _____________________________________________ 29

6. Approval of Labor-Based Deferred Action ______________________________________________ 29

7. Denials __________________________________________________________________________ 29

E. Special Circumstances _________________________________________________________ 30

1. Labor-Based Deferred Action Applicants with Significant Negative Equities (Criminal/Immigration

History) _______________________________________________________________________________ 30

2. Applying for only Labor-Based Deferred Action, without Applying for Work Authorization _______ 30

1

The manual is intended for authorized immigration practitioners and is not a substitute for independent

legal advice provided by immigration practitioners familiar with a client’s case. Practitioners should

independently confirm whether the law has changed since the date of this publication. The authors of this

practice manual are Mary Yanik (Tulane Immigrant Rights Clinic), Jessica Bansal (Unemployed Workers

United), Ann Garcia (National Immigration Project (NIPNLG)), and Lynn Damiano Pearson (National

Immigration Law Center). The authors would like to thank Bliss Requa-Trautz (Arriba Las Vegas

Workers Center), Cal Soto (National Day Laborer Organizing Network), Debbie Smith and Claudia

Lainez (Service Employees International Union), Shelly Anand, Elizabeth Zambrana, and Alessandra

Stevens (Sur Legal Collaborative), Angel Graf (Immigration Center for Women and Children), Stacy

Tolchin (Law Offices of Stacy Tolchin), Audrey Richardson (Greater Boston Legal Services), Anna Hill

Galendez (Michigan Immigrant Rights Center), Michelle Lapointe (National Immigration Law Center),

Lisa Palumbo (Legal Aid Chicago), Kristen Shepherd (University of Georgia School of Law Community

Health Partnership Clinic), Laura Garza (Arise Chicago), and Christina Maloney (Centro de los Derechos

del Migrante, Inc.) for their review and contributions to the practice manual.

2

III. Subsequent Requests for Deferred Action after Initial Approval (Renewals) _______ 32

IV. Other Types of Immigration Relief Stemming from Labor Disputes______________ 33

A. Prosecutorial Discretion in Removal Proceedings __________________________________ 33

B. Parole in Place _______________________________________________________________ 34

C. Requests for Noncitizens Presently Outside the United States ________________________ 36

D. Other related relief–T & U Nonimmigrant Visas ___________________________________ 38

1. Identifying Labor Trafficking & Eligibility for T Nonimmigrant Status ________________________ 40

2. Identifying Labor-Based Qualifying Crimes for Eligibility for U Nonimmigrant Status ___________ 40

V. Frequently Asked Questions _______________________________________________ 42

A. Advance Parole & Travel Outside the United States ________________________________ 42

B. Civil Rights Cases & Private Rights of Action _____________________________________ 43

VI. Appendices ___________________________________________________________ 44

Appendix 1: Timeline of Prior DHS Guidance on Labor Disputes _________________________ 44

Appendix 2: Template Request for a Statement of Interest from Labor or Employment Agency47

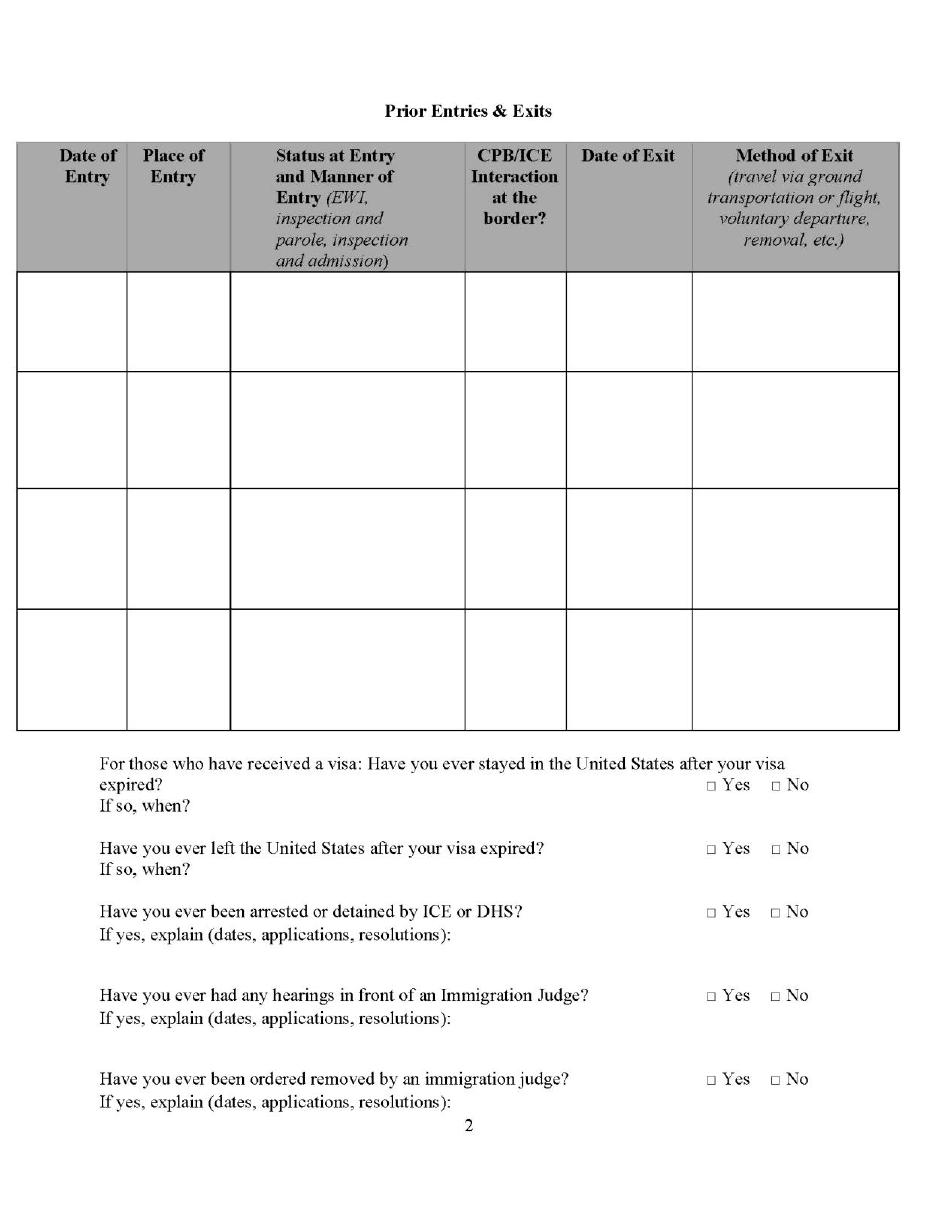

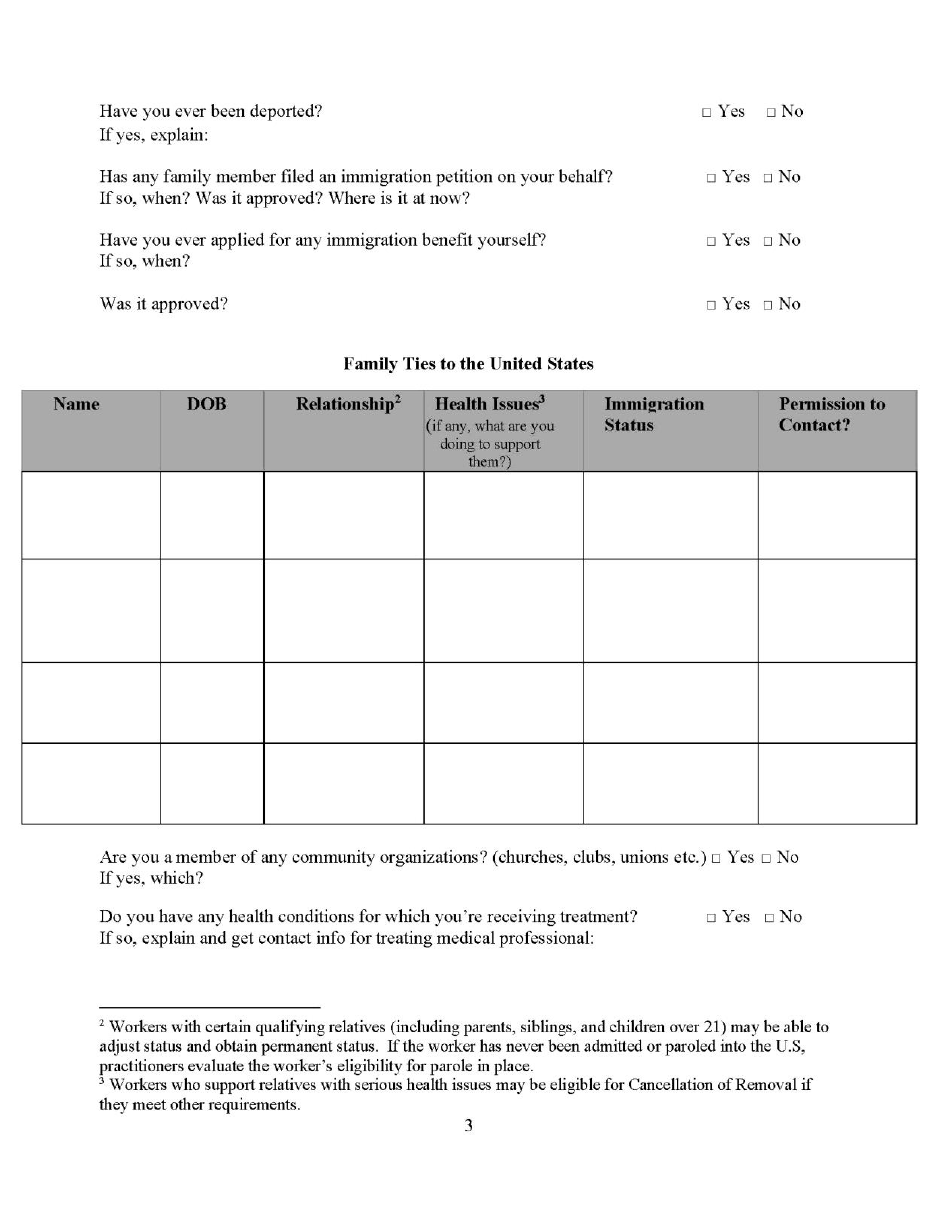

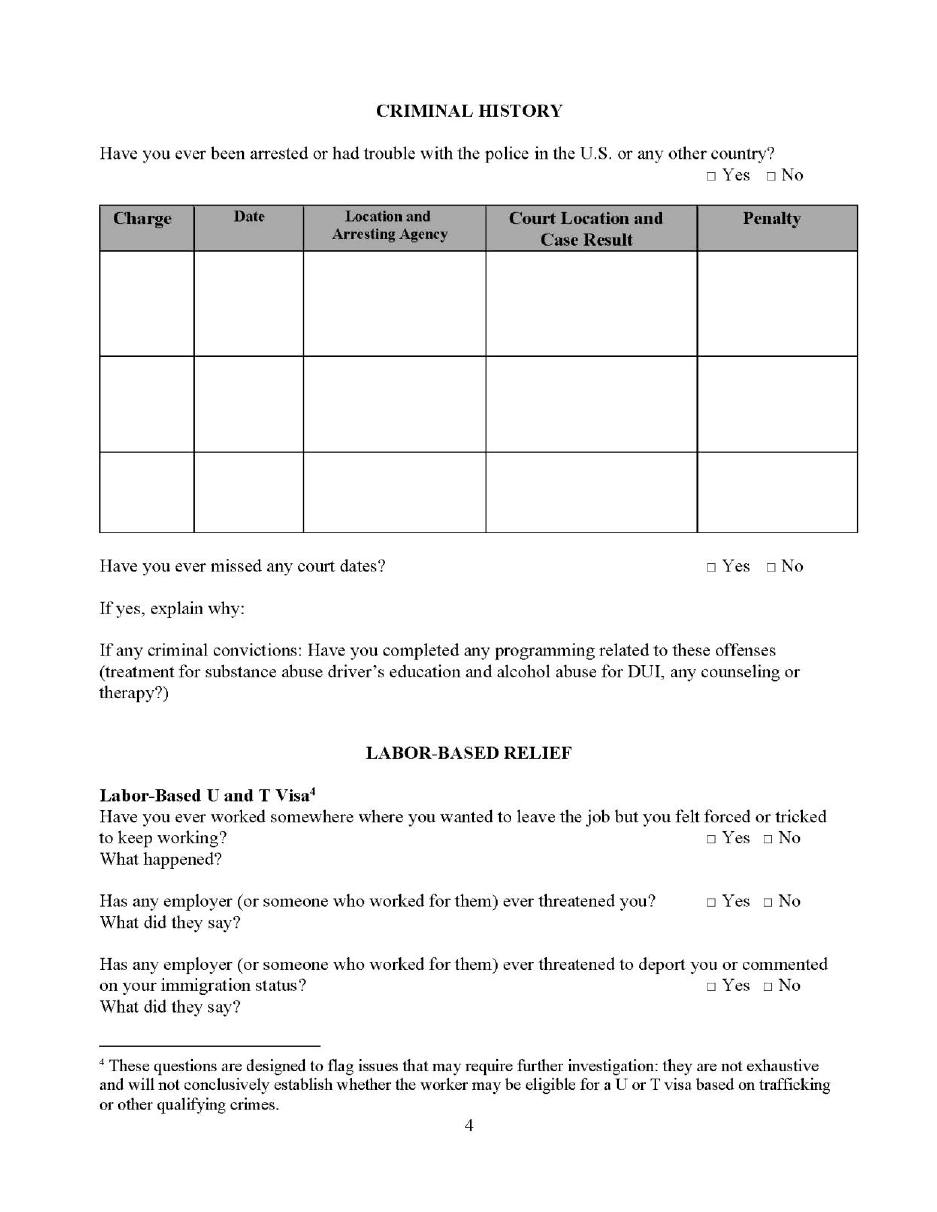

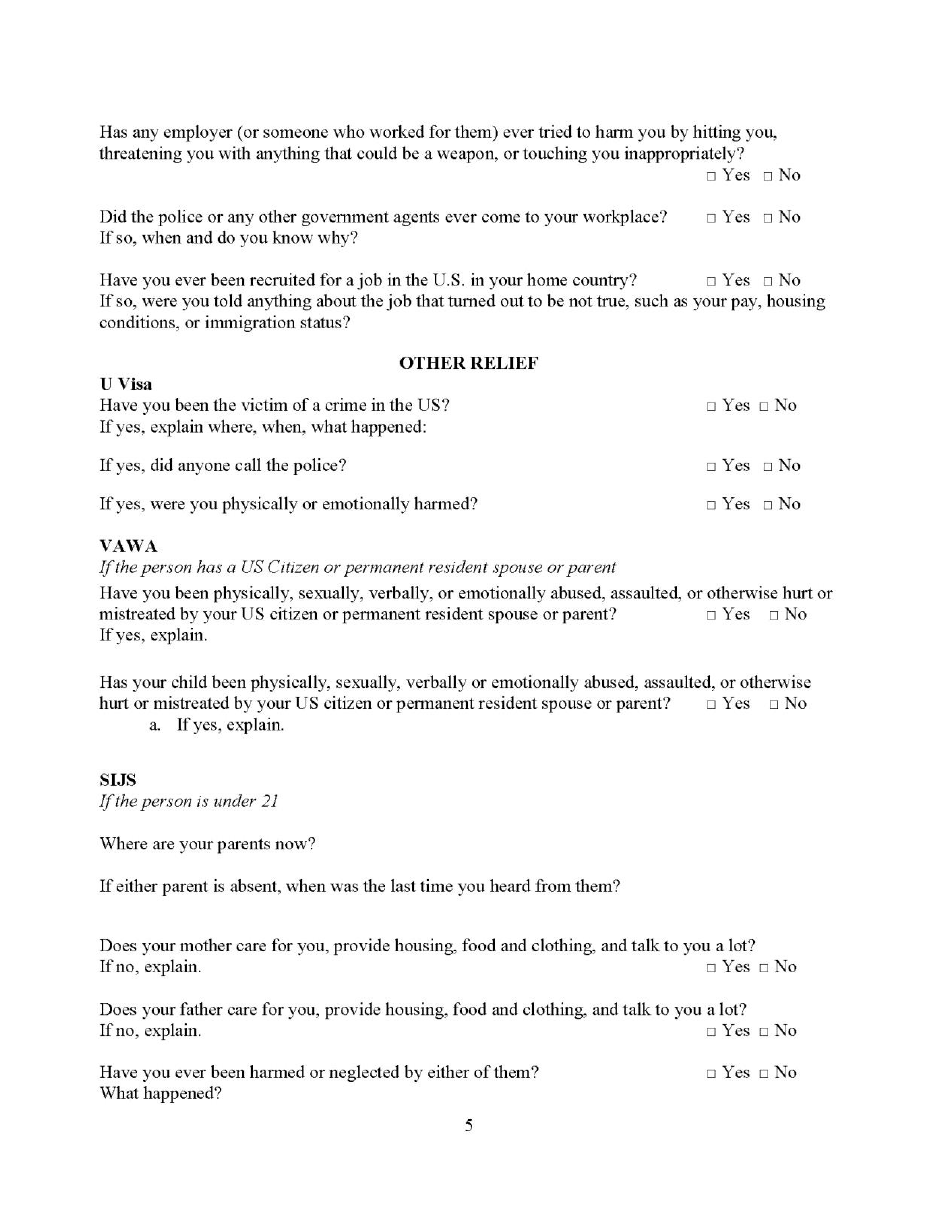

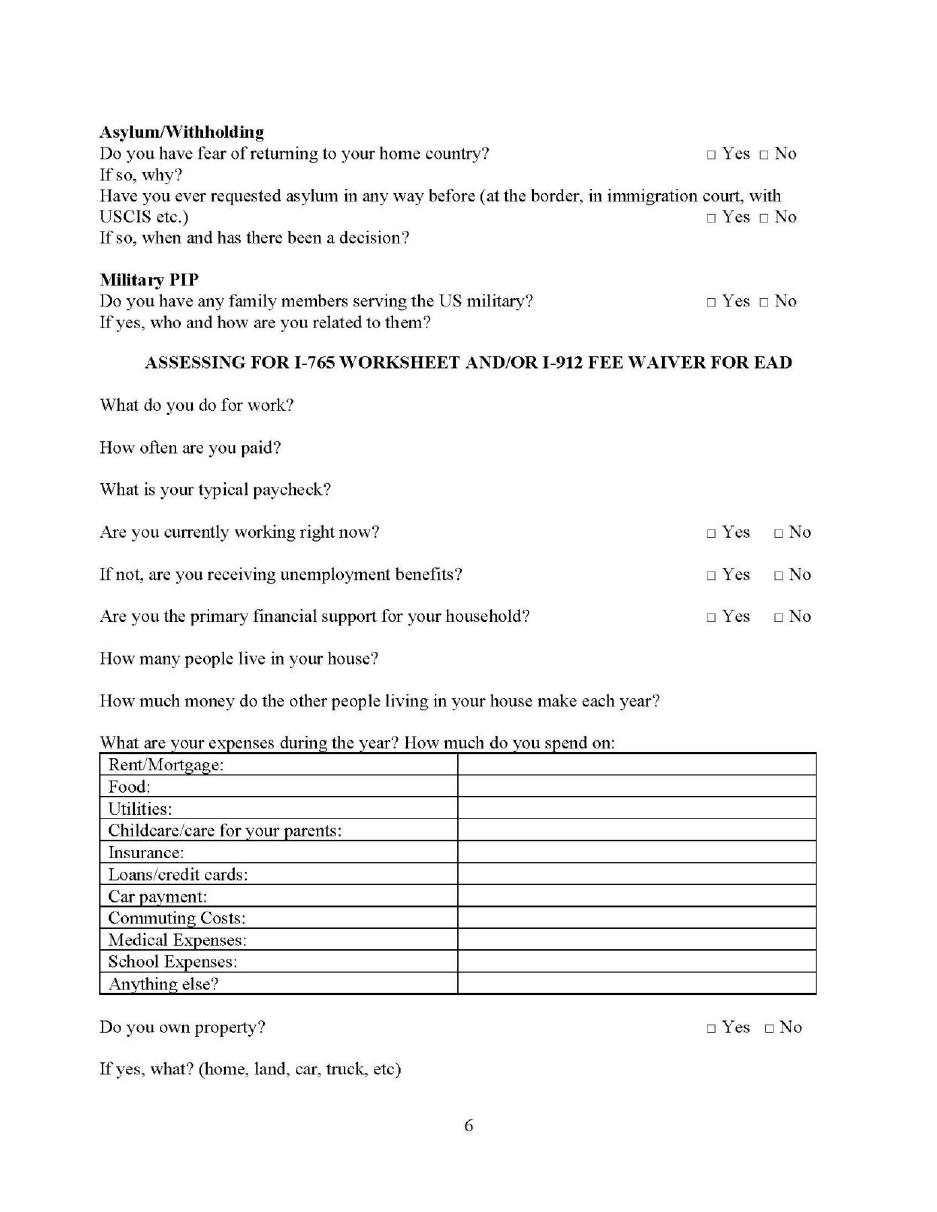

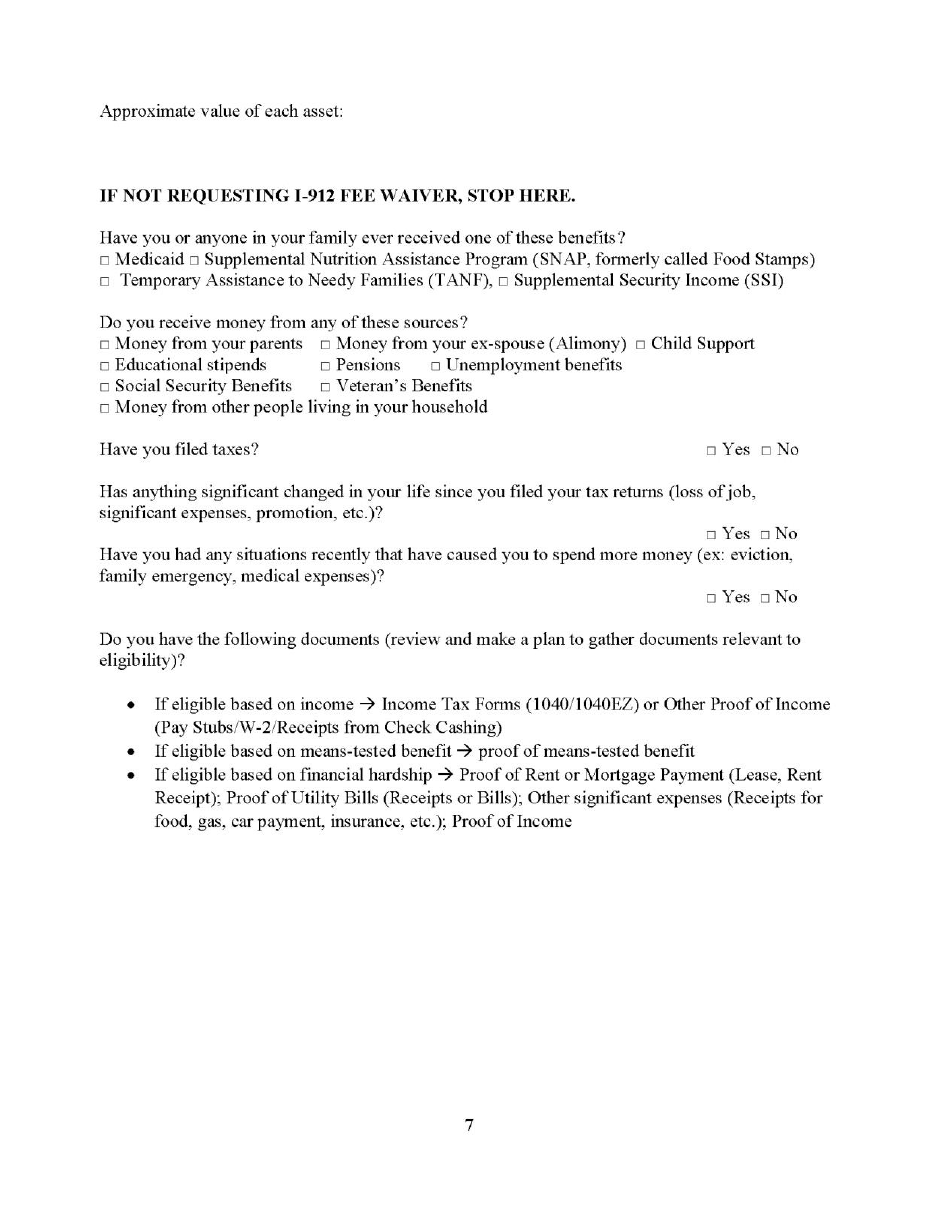

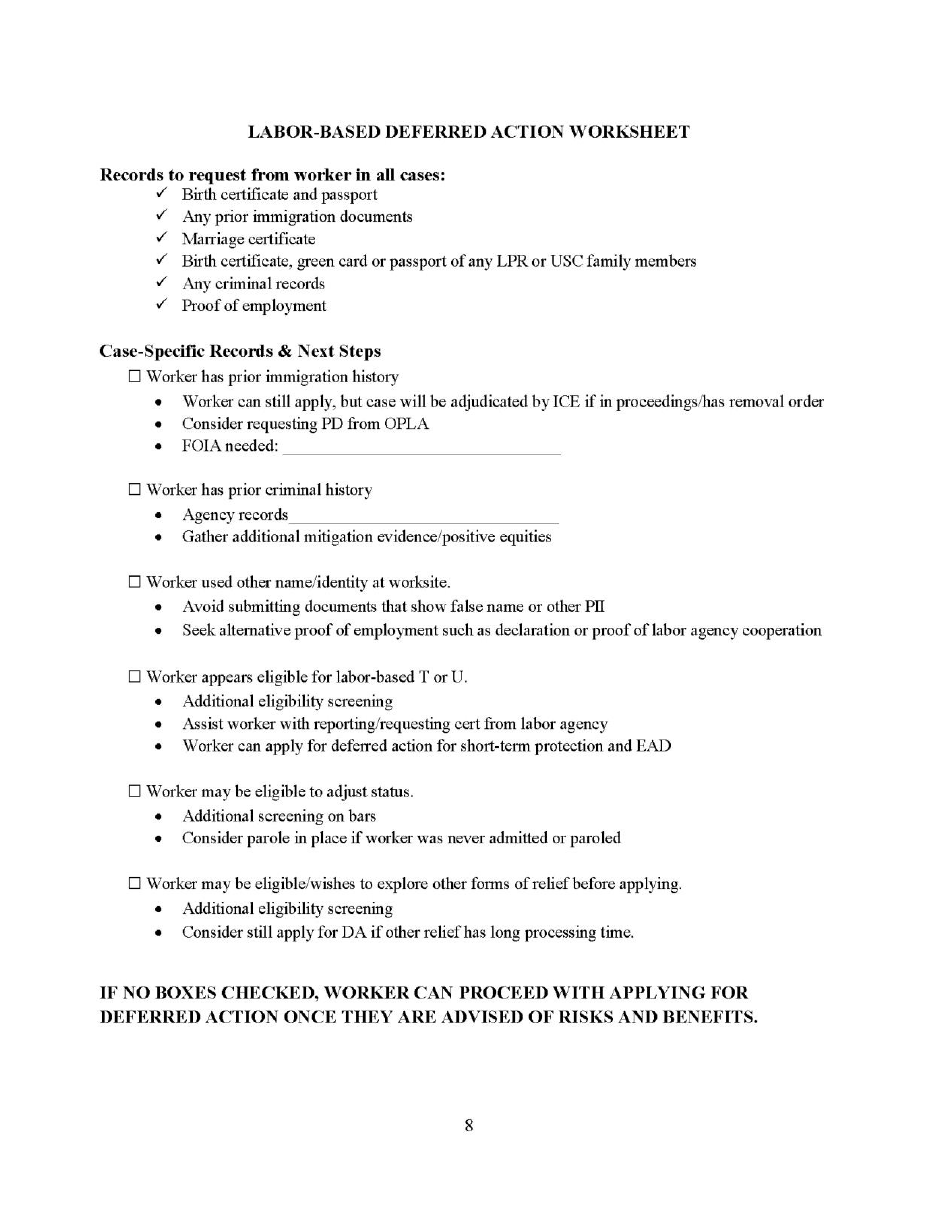

Appendix 3: Intake Form for Labor-Based Deferred Action and Employment Authorization __ 49

Appendix 4: Sample Labor Agency Statements of Interest _______________________________ 57

Appendix 5: Sample Cover Letter Requesting Labor-Based Deferred Action _______________ 57

Appendix 6: Sample Declaration Regarding Employment and Request from Labor-Based

Deferred Action Applicant _________________________________________________________ 57

Appendix 7: Sample I-765 Worksheet ________________________________________________ 57

Appendix 8: Redacted Labor-Based Deferred Action Approval Letter _____________________ 57

I. Introduction

On January 13, 2023, the Department of Homeland Security announced “a streamlined and

expedited deferred action request process” for non-citizen workers who experience or witness

labor rights violations [hereinafter, “Labor-Based Deferred Action”].

2

Guidance on the process

emphasizes DHS’s role in supporting federal, state, and local labor and employment agency

efforts to enforce labor and employment law and hold abusive employers accountable. Labor-

Based Deferred Action confers deferred action and work authorization for a two-year period.

Those approved may make subsequent requests for additional two-year grants of Labor-Based

Deferred Action if supported by the labor or employment agency. Labor-Based Deferred Action

represents the culmination of over a decade of worker-led organizing to demand concrete

protections against immigration-based retaliation by exploitative employers. It is a testament to

the courage of immigrant workers who have stood up for workers’ rights in the face of retaliatory

immigration enforcement.

2

Press Release, U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., DHS Announces Process Enhancements for Supporting

Labor Enforcement Investigations (Jan. 13, 2023), https://www.dhs.gov/news/2023/01/13/dhs-announces-

process-enhancements-supporting-labor-enforcement-investigations [hereinafter “DHS Announcement”].

3

This Practice Manual is intended for immigration practitioners representing workers applying for

Labor-Based Deferred Action. Part II describes who is eligible and explains the application

process, including components of the application packet and practice advice. Part III addresses

subsequent requests (renewals) after the initial two-year period. Part IV describes related relief,

such as prosecutorial discretion in removal proceedings, parole, and U and T Visas. Finally, Part

V answers frequently asked questions. Publicly available appendices begin with a timeline of key

DHS memoranda and agreements that incrementally addressed the conflict between immigration

and labor enforcement, laying the groundwork for the January 13 guidance, and also include a

template request for a Statement of Interest from a labor or employment agency and an intake

form. Practitioners may view the five additional appendix documents referenced throughout this

practice manual by completing the following form:

https://tulane.co1.qualtrics.com/jfe/form/SV_3TYmLAhHX5k2hBY.

For immigration-related technical assistance questions on Labor-Based Deferred Action,

practitioners may contact: Mary Yanik (myanik@tulane.edu), Lynn Damiano Pearson

(daforworkers@nilc.org), and Ann Garcia (members of the National Immigration Project

(NIPNLG) only, ann@nipnlg.org).

II. Applying for Labor-Based Deferred Action

A. What is Deferred Action?

Deferred action is a discretionary determination by DHS to defer removal as an act of

prosecutorial discretion.

3

The legacy Immigration and Naturalization Service formally

recognized deferred action as a form of prosecutorial discretion in 1975, indicating that deferred

action was warranted when “adverse action would be unconscionable because of the existence of

appealing humanitarian factors.”

4

While DHS has therefore long held authority to consider

deferred action for a variety of humanitarian reasons, the application process has been obscure.

DHS has not published information on how to apply for deferred action generally, although it has

sometimes provided policy guidance on how the agency will consider requests from certain

applicants, such as families of U.S. Armed Forces members.

5

3

See U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., DHS Support of the Enforcement of Labor and Employment Laws,

https://www.dhs.gov/enforcement-labor-and-employment-laws (last updated Feb. 3, 2023) [hereinafter

“DHS FAQ”]. While the DHS guidance issued on January 13, 2023 specifically references both deferred

action and parole-in-place as forms of prosecutorial discretion available to the agency, the Labor-Based

Deferred Action Process relies exclusively on deferred action. Id. For more on parole in place, see infra

Part IV Section B.

4

(Legacy) Immigration and Naturalization Service, Operating Instructions, O.I. § 103.1(a)(1)(ii) (1975).

5

See Memorandum from Jeh Johnson, Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., to León Rodriguez, Dir.,

U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Families of U.S. Armed Forces Members and Enlistees (Nov. 20,

2014),

https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/14_1120_memo_parole_in_place.pdf; see also U.S.

Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Discretionary Options for Military Members, Enlistees, and their Families,

https://www.uscis.gov/military/discretionary-options-for-military-members-enlistees-and-their-families

(last updated Apr. 25, 2022).

4

DHS makes determinations to grant or deny deferred action on a case-by-case basis and a grant

of deferred action can be terminated at any time at the agency’s sole discretion. There is no

statutory or regulatory limit to the length of time for which deferred action can be granted.

However, historically, deferred action has been granted for periods of two to three years.

6

Individuals with deferred action are eligible for an employment authorization document with a

basic showing of economic necessity.

7

Through applying for employment authorization, or

separately, deferred action recipients can also apply for a Social Security card.

8

Social Security

cards issued to deferred action recipients state, “Valid for Work Only with DHS Authorization,”

because they do not establish employment eligibility on their own, so they must be presented

with evidence of employment authorization when used for employment eligibility verification.

9

Only noncitizens residing in the U.S. can seek deferred action. Deferred action does not

authorize entry into the U.S. Therefore, noncitizens who receive deferred action will not be able

to travel and re-enter the country without separate authorization.

10

A grant of deferred action authorizes the noncitizen’s presence in the United States. Therefore,

while deferred action does not cure unlawful presence already accrued for the purposes of the 3-

and 10-year bars, time spent in the U.S. under deferred action will not count toward the

accumulation of unlawful presence.

11

6

See Ben Harrington, Cong. Research Serv. R45158, An Overview of Discretionary Reprieves from

Removal: Deferred Action, DACA, TPS, and Others (2018),

https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45158; but see U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs.,

National Engagement - U Visa and Bona Fide Determination Process - Frequently Asked Questions,

https://www.uscis.gov/records/electronic-reading-room/national-engagement-u-visa-and-bona-fide-

determination-process-frequently-asked-questions (last updated Sept. 23, 2021) (stating that the initial

Bona Fide Determination Deferred Action grant is valid for four years).

7

8 C.F.R. § 274a.12(c)(14). While USCIS is not permitted to waive the employment authorization

application fee for applicants for DACA, 8 C.F.R. § 274a.12(c)(33), that provision does not prohibit fee

waiver for other types of deferred action, including Labor-Based Deferred Action.

8

The Social Security Administration and USCIS have now streamlined the process for requesting a SSN

such that relevant questions are included in the I-765. A SSN is automatically sent if employment

authorization is approved. For more on this streamlined process, as well as what to do if your client does

not receive the SSN, see Soc. Sec. Admin., Apply For Your Social Security Number While Applying For

Your Work Permit and/or Lawful Permanent Residency, https://www.ssa.gov/ssnvisa/ebe.html (last

visited March 10, 2023).

9

U.S. employers fill out Form I-9 for each person they hire to verify the employee’s identity and

employment authorization based on the documents they present. For more information about the I-9 form

and the list of acceptable documents, see U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., I-9: Employment Eligibility

Verification (Dec. 20, 2022), https://www.uscis.gov/i-9.

10

It is not yet clear how USCIS will adjudicate requests for advance parole for travel from Labor-Based

Deferred Action recipients. For further discussion of advance parole, see infra Part V Section A.

11

Adjudicator’s Field Manual, U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., ch. 40.9(b)(3)(J); Arizona Dream Act

Coal. v. Brewer, 855 F.3d 957, 974 (9th Cir. 2017) (en banc); Texas v. United States, 809 F.3d 134, 147–

48 (5th Cir. 2015) (explaining that deferred action recipients are “lawfully present” based on agency

memoranda); see also DHS FAQ, supra note 3 (“a noncitizen granted deferred action is considered

lawfully present in the United States for certain limited purposes while the deferred action is in effect”).

5

Those who receive deferred action, employment authorization, and a Social Security number are

eligible to receive valid state identification, including driver’s licenses, in every state.

12

Deferred

action grantees can receive Social Security benefits if they are otherwise entitled to them.

13

However, deferred action grantees are not considered “qualified aliens” for purposes of receiving

federal public benefits.

14

B. Who is Eligible for Labor-Based Deferred Action?

15

Labor-Based Deferred Action is available to “[n]oncitizen workers who are victims of, or

witnesses to, the violation of labor rights.”

16

As a threshold matter, to establish eligibility,

workers must provide “[a] letter or Statement of Interest from a [federal, state, or local] labor or

employment agency addressed to DHS supporting the request.”

17

[hereinafter, “Statement of

Interest”]. Applications submitted without a Statement of Interest will be rejected. Generally,

labor and employment agencies will issue Statements of Interest only in connection with agency

investigations or enforcement efforts (including, in some cases, closed investigations).

12

DHS Guidance on DACA makes clear that those with DACA or other deferred action are considered

lawfully present. See U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Consideration of Deferred Action for Childhood

Arrivals (DACA) Frequently Asked Questions (Nov. 3, 2022),

https://www.uscis.gov/humanitarian/consideration-of-deferred-action-for-childhood-arrivals-

daca/frequently-asked-questions#miscellaneous (see questions Q4, explaining that DACA is identical to

any other grant of deferred action, and Q5, explaining that those with deferred action are lawfully present

for the purposes of certain public benefits). This means that deferred action recipients can receive

federally recognized driver’s licenses or identification that are valid under the REAL ID Act. See Nat’l

Immigr. Law Ctr., REAL ID and Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) (Jan. 2023),

https://www.nilc.org/issues/daca/real-id-and-daca/. While some states have attempted to deny licenses to

noncitizens with deferred action, those efforts have been stymied by litigation or legislative action and all

states are currently issuing state identification to deferred action grantees. For information on further

developments in this area, see Nat’l Immigr. Law Ctr., Access to Driver’s Licenses for Immigrant Youth

Granted DACA (Jul. 22, 2020) https://www.nilc.org/issues/drivers-licenses/daca-and-drivers-licenses/.

13

Noncitizens in the U.S. must be in lawfully present to receive Social Security Benefits. See 42 U.S.C.

§ 402(y).

14

Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act of 1996 (PRWORA), Pub. L. No.

104–193, 110 Stat. 2105 (Aug. 22, 1996), § 431(b). For more information on benefit eligibility, see Tanya

Broder, Gabrielle Lessard, & Avideh Moussavian, Nat’l Immigr. Law Ctr., Overview of Immigration

Eligibility for Federal Programs (Oct. 2022), https://www.nilc.org/issues/economic-support/overview-

immeligfedprograms/ - _ftnref1.

15

This Section includes a cursory overview of labor and employment aspects of the Labor-Based

Deferred Action process. A separate practice resource is forthcoming that will specifically focus on the

labor and employment issues involved in Labor-Based Deferred Action. It will be co-authored by Jobs

with Justice, the National Employment Law Project (NELP), and the National Immigration Law Center

(NILC).

16

DHS Announcement, supra note 2.

17

DHS FAQ, supra note 3.

6

To be eligible for Labor-Based Deferred Action, a worker must therefore: (1) Witness or

experience a violation of labor or employment law or other labor dispute;

18

(2) File a complaint

with a federal, state, or local labor or employment agency or identify an existing agency

investigation related to the violation;

19

and (3) Obtain a Statement of Interest.

Labor and employment agency complaint and Statement of Interest request processes are

generally intended to be accessible to workers proceeding pro se. However, in practice,

assistance from experienced attorney or non-attorney advocates is often necessary to ensure a

strong complaint, thorough investigation, and successful request.

20

Workers centers, unions,

labor organizers, and labor and employment attorneys are often experts in this area. Immigration

practitioners are not typically involved unless they are experienced in labor and employment law

or partner with others who are. Accordingly, in most cases, immigration practitioners will

become involved in the case after the worker has requested or obtained a Statement of Interest

from the labor agency.

21

18

Department of Labor (DOL) guidance on the process for requesting DOL support for Labor-Based

Deferred Action describes workers who experience or witness violations of labor or employment law as

“workers involved in labor disputes.” U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Process for Requesting Department of Labor

Support for Requests to the Department of Homeland Security for Immigration-Related Prosecutorial

Discretion During Labor Disputes (Jul. 6, 2022),

https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/files/Process-For-Requesting-Department-Of-Labor-

Support-FAQ.pdf [hereinafter “DOL FAQ”]. The term “labor dispute” is broadly defined as “a labor-

related dispute between the employees of a business of organization and the management or ownership of

the business or organization concerning the following employee rights: the right to be paid the minimum

legal wage, a promised or contracted wage, and overtime; the right to receive family medical leave and

employee benefits to which one is entitled; the right to have a safe workplace and to receive

compensation for work-related injuries; the right to be free from unlawful discrimination; the rights to

form, join or assist a labor organization, to participate in collective bargaining or negotiation, and to

engage in protected concerted activities for mutual aid or protection; the rights of members of labor

unions to union democracy, to unions free of financial improprieties, and to access to information

concerning employee rights and the financial activities of unions, employers, and labor relation

consultants; and the right to be free from retaliation for seeking to enforce the above rights.”

U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec. and U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Revised Memorandum of Understanding between

the Departments of Homeland Security and Labor Concerning Enforcement Activities at Worksites (Dec.

7, 2011), https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/DHS-DOL-MOU_4.19.18.pdf.

19

Note that some labor and employment agencies allow anonymous and/or third-party complaints.

20

This is particularly true where workers face barriers to navigating agency processes (such as fear of

government officials in the U.S., literacy, and language).

21

Immigration practitioners are nonetheless encouraged to screen potential clients for labor abuses as they

may identify potential eligibility for Labor-Based Deferred Action or other types of labor-based

immigration relief. Practitioners should consider identifying labor rights organizations in their

communities where they can refer workers who need assistance reporting labor and employment law

violations and potentially requesting Statements of Interest. For further discussion of screening best

practices, see infra Section II Part C.

7

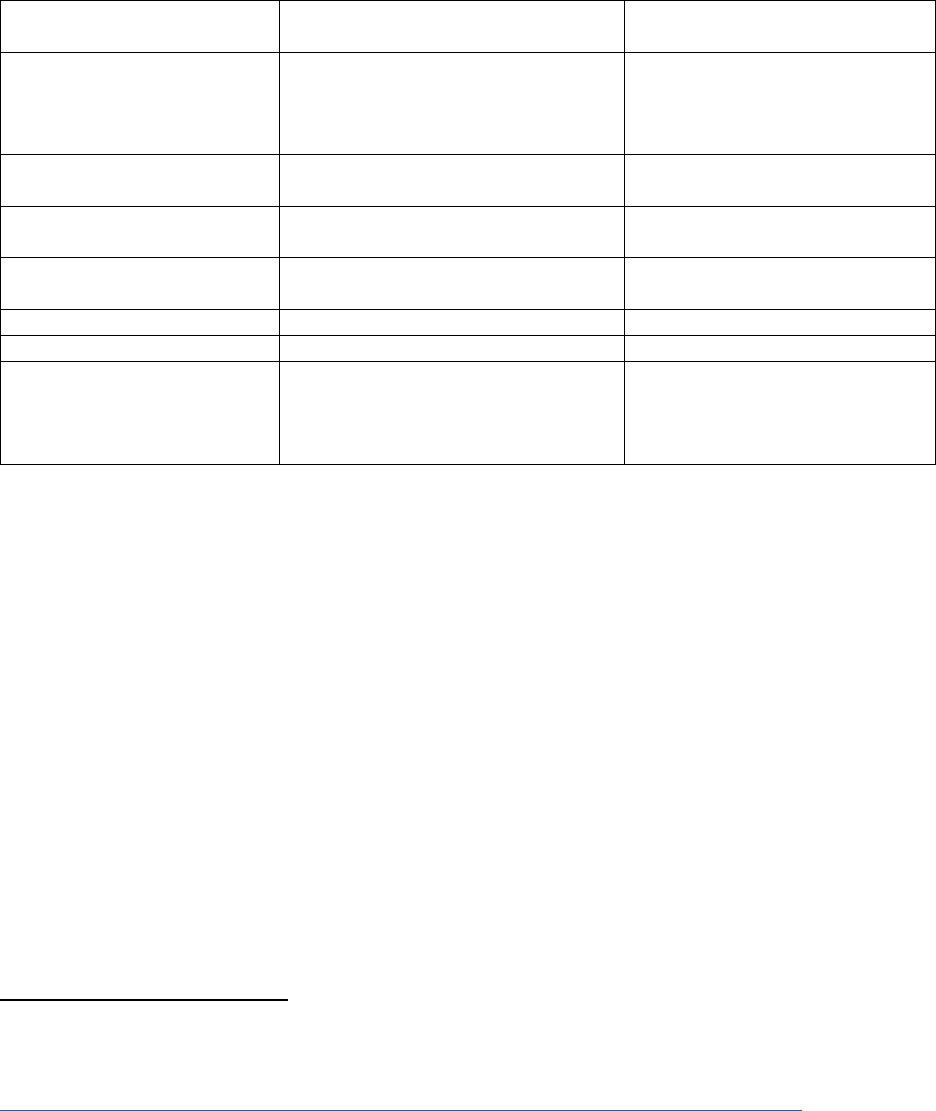

1. Identifying and Reporting Labor and Employment Law Violations

Generally, labor and employment agencies issue Statements of Interest only in connection with

agency investigations or enforcement efforts. If a worker has experienced or witnessed a

violation that relates to an existing agency investigation or enforcement effort, the worker does

not need to file a new complaint with the agency before requesting a Statement of Interest.

Rather, as described below in Part II Section B, the worker can simply describe how their

experience relates to the agency’s existing investigation or enforcement effort.

22

If a worker has

experienced or witnessed a violation that is not already the subject of an agency investigation or

enforcement effort, the worker may be able to initiate an investigation by filing their own

complaint.

23

While a full discussion of labor and employment law is beyond the scope of this Practice

Manual, Table 1 provides a very basic overview of some of the principal federal laws enforced

by key federal labor and employment agencies, with links to agency complaint processes.

Practitioners should be aware that coverage varies from law to law and is sometimes limited to

employers with a certain number of employees or volume of business, and/or employees with a

22

See U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, EEOC’s Support for Immigration-Related

Deferred Action Requests to the DHS Frequently Asked Questions, https://www.eeoc.gov/faq/eeocs-

support-immigration-related-deferred-action-requests-dhs (last visited Mar. 10, 2023) [hereinafter “EEOC

FAQ”].

23

Often, the best way to determine whether there is already a pending investigation is to ask the worker if

they are aware of anyone else filing a complaint about the violation. In addition, it may be helpful to

search publicly available case databases maintained by the NLRB, Nat’l Labor Relations Bd., Cases &

Decisions, https://www.nlrb.gov/cases-decisions (last visited Mar. 10, 2023), and the DOL, U.S. Dep’t of

Labor, Data Enforcement, https://enforcedata.dol.gov/views/search.php (last visited Mar. 10, 2023). For a

general guide on intake to screen for labor disputes relevant to prosecutorial discretion, see Screening for

Civil and Labor Rights Violations in Support of Prosecutorial Discretion (Aug. 5, 2021),

https://www.nelp.org/wp-content/uploads/Intake-Guide-Screening-Civil-and-Labor-Rights-Violations-in-

Support-of-Prosecutorial-Discretion-8-5-2021.pdf.

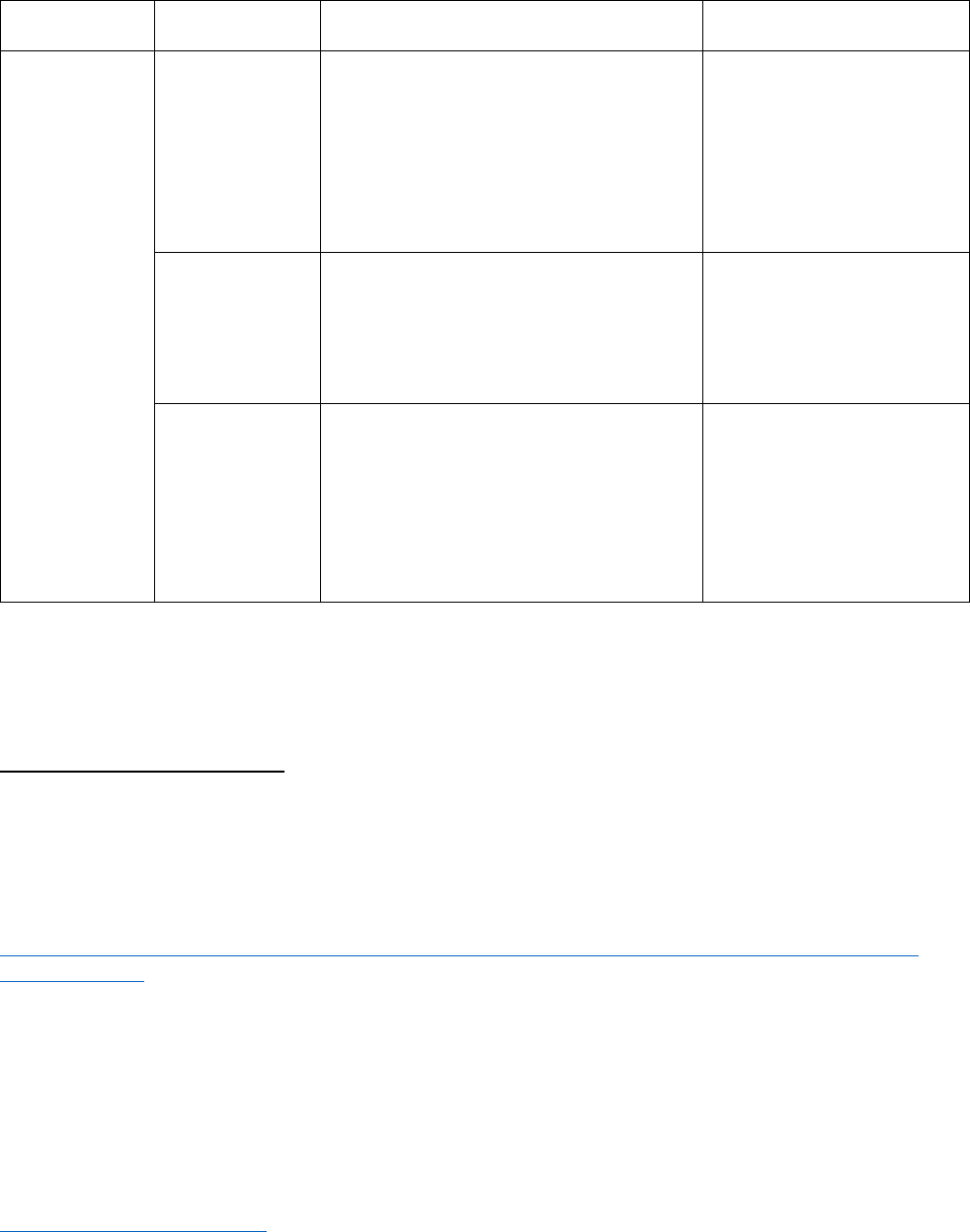

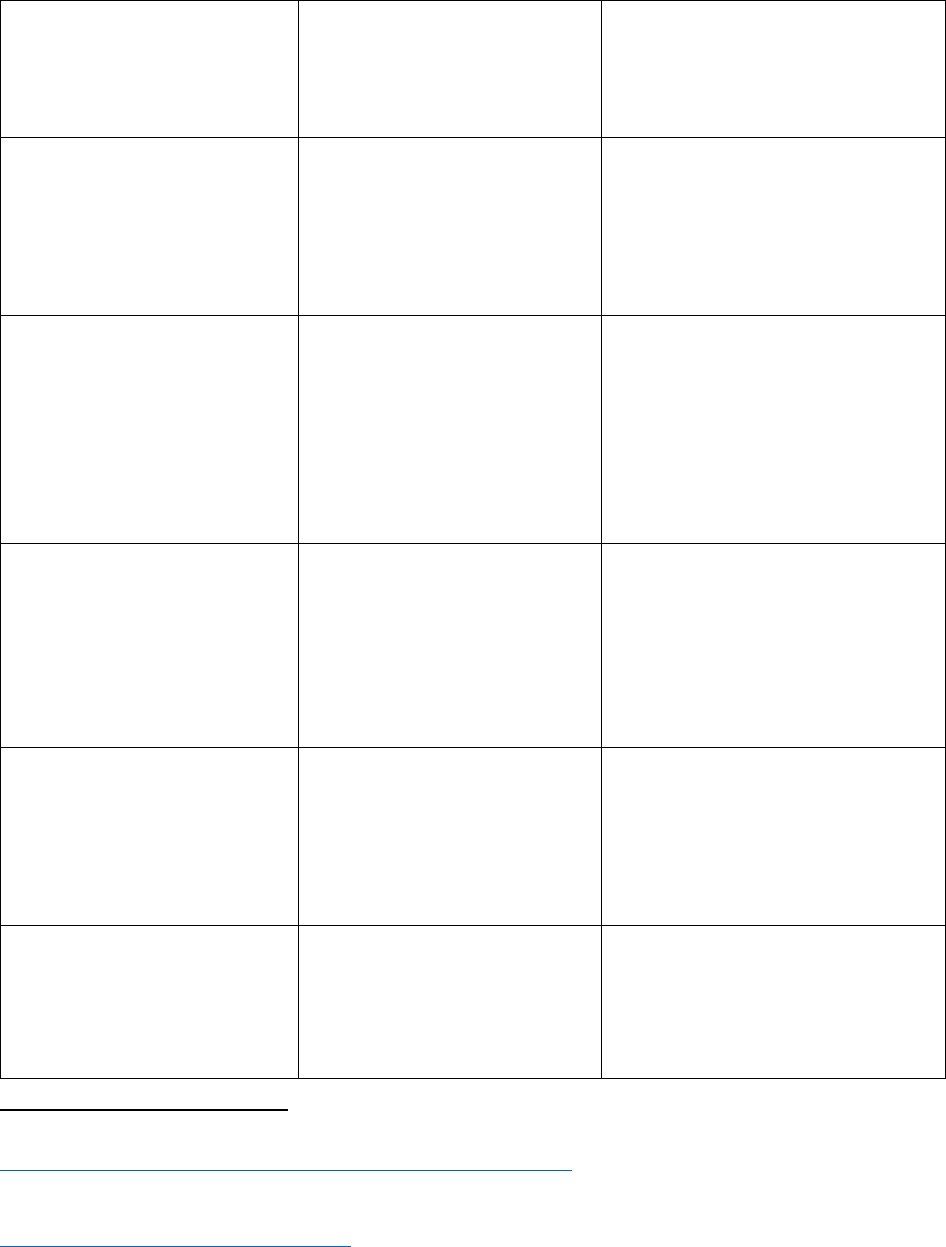

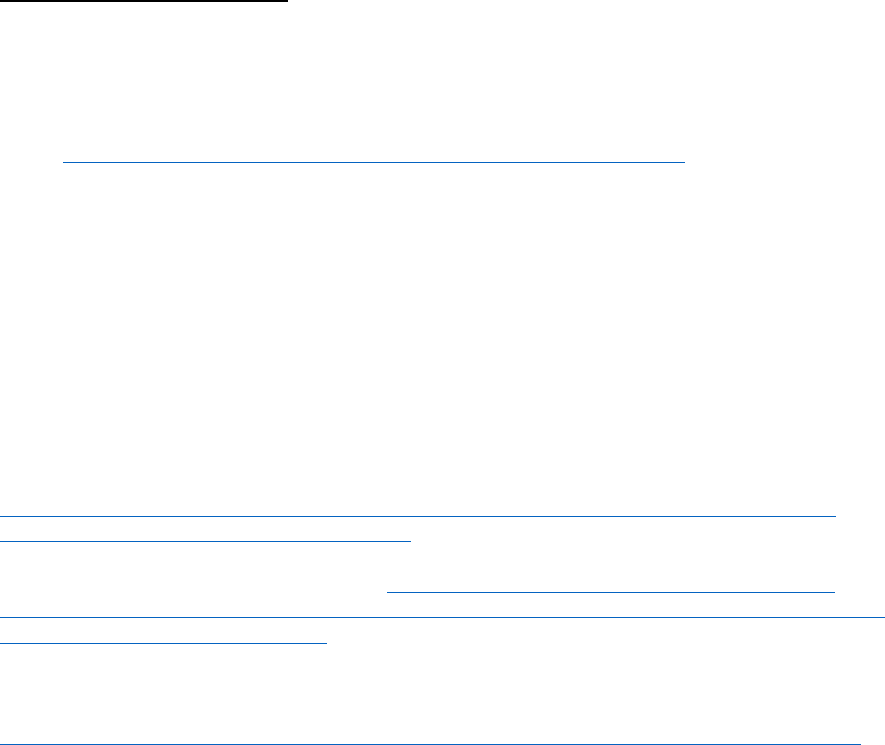

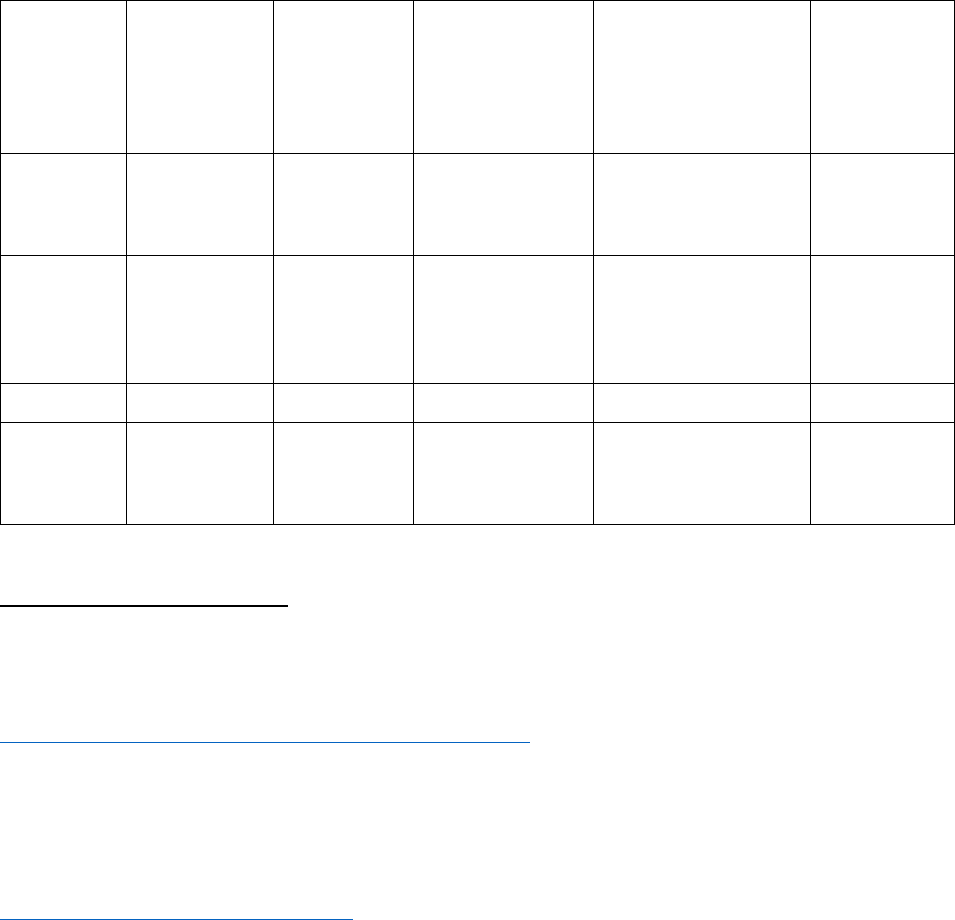

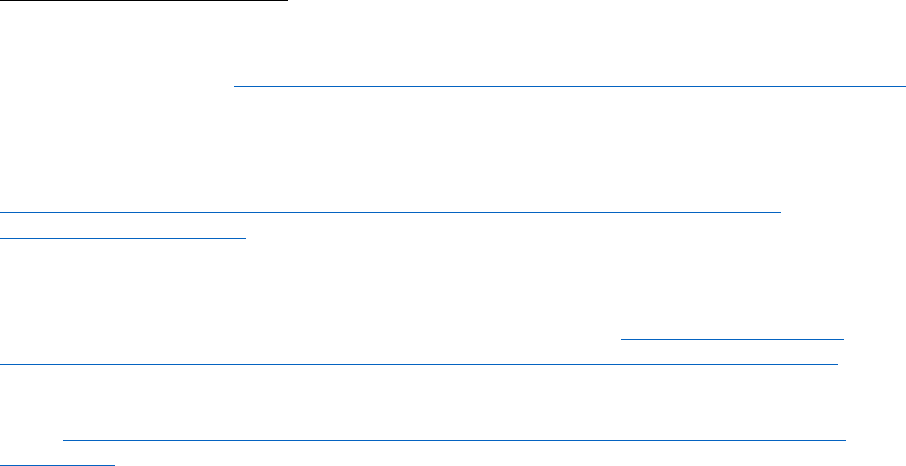

1. Witness or

Experience a

Labor Violation or

Participate in a

Labor Dispute

2. File Labor

Agency Complaint

3. Obtain Labor

Agency Statement

of Interest

4. Screening &

Counseling for

Individual

Workers Within

Scope of Labor

Agency Statement

5. File Individual

Application(s) for

Deferred Action &

Work Permit

6. File Subsequent

Requests for

Deferred Action &

Work Permit

8

certain amount of time worked.

24

State and local labor laws may provide more expansive labor

protections than federal law, and state and local labor agencies often have their own complaint

processes.

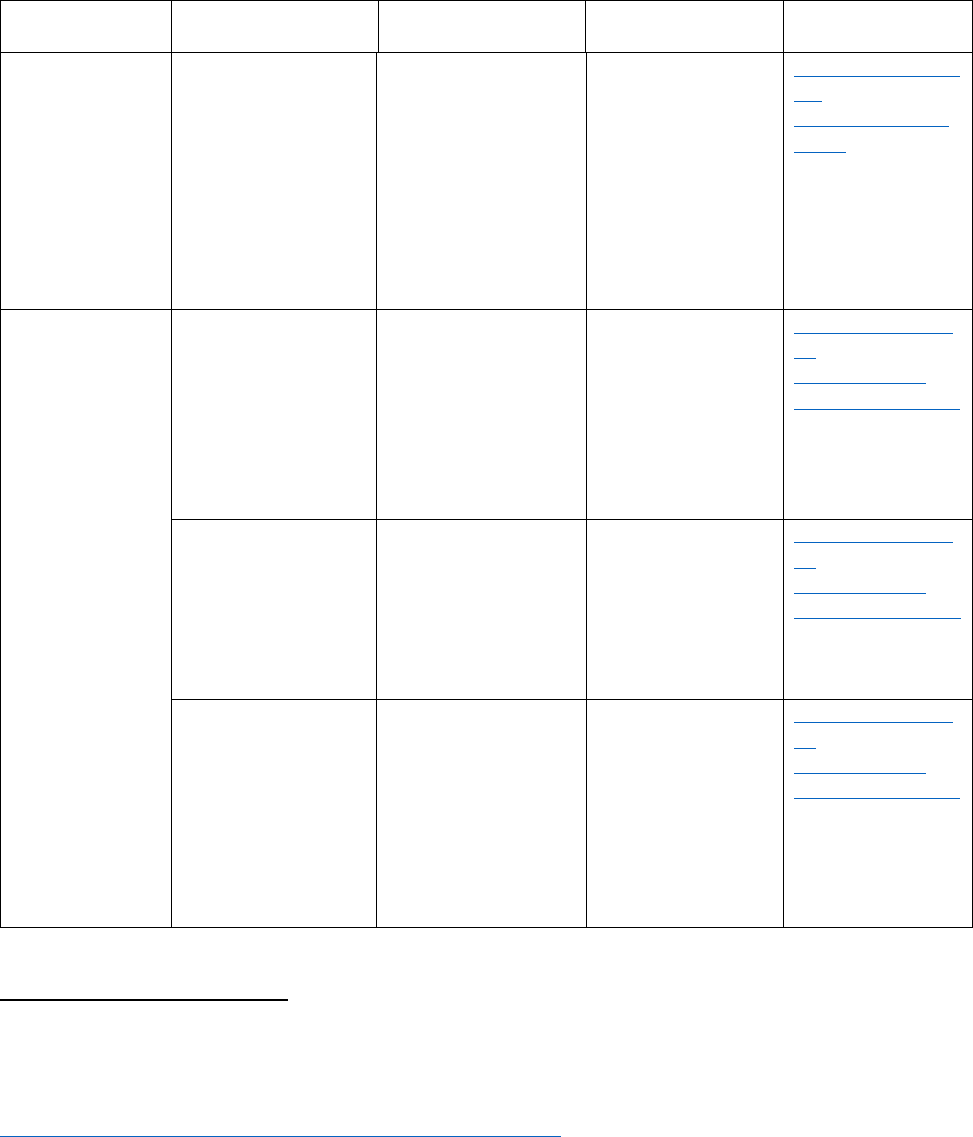

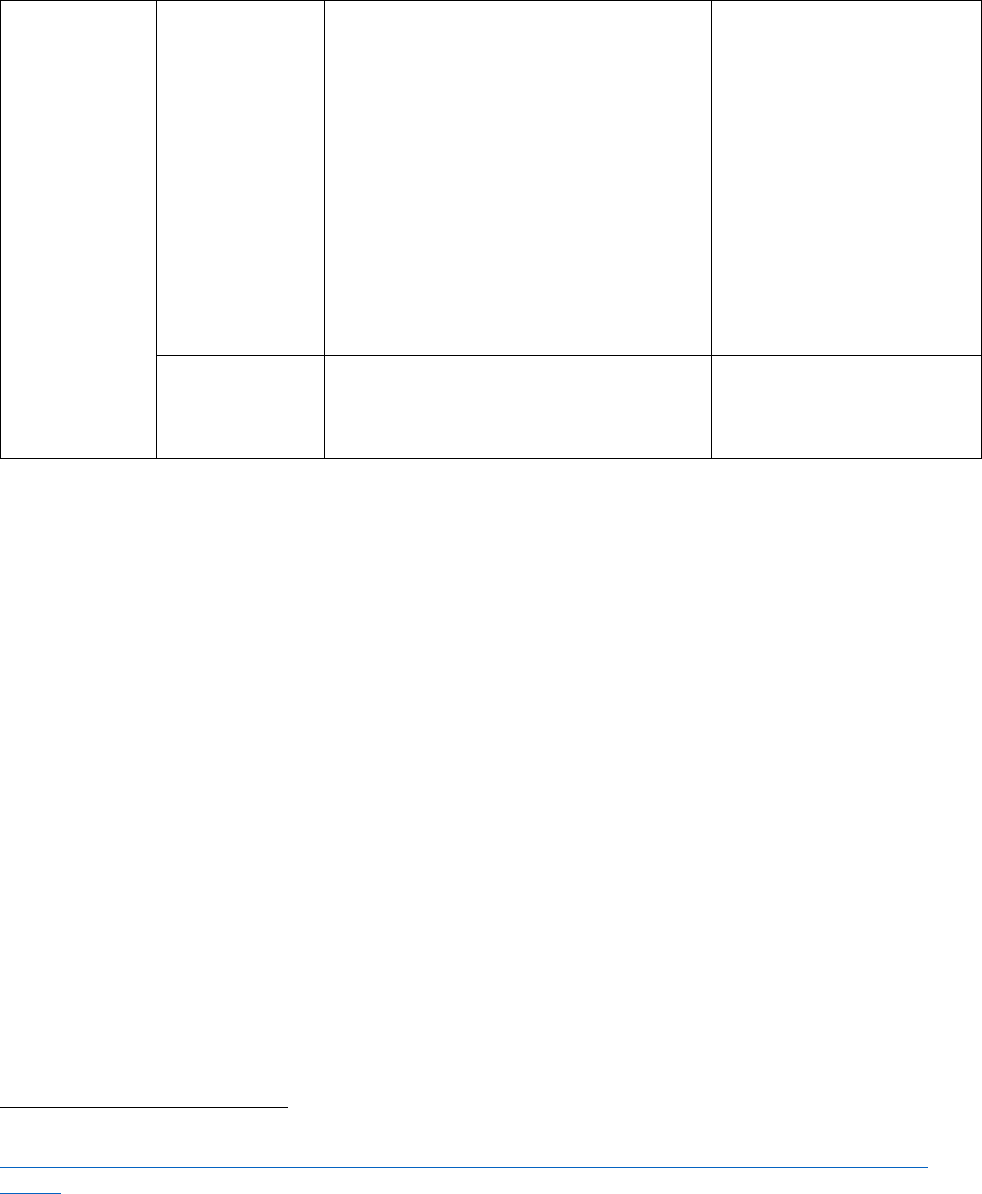

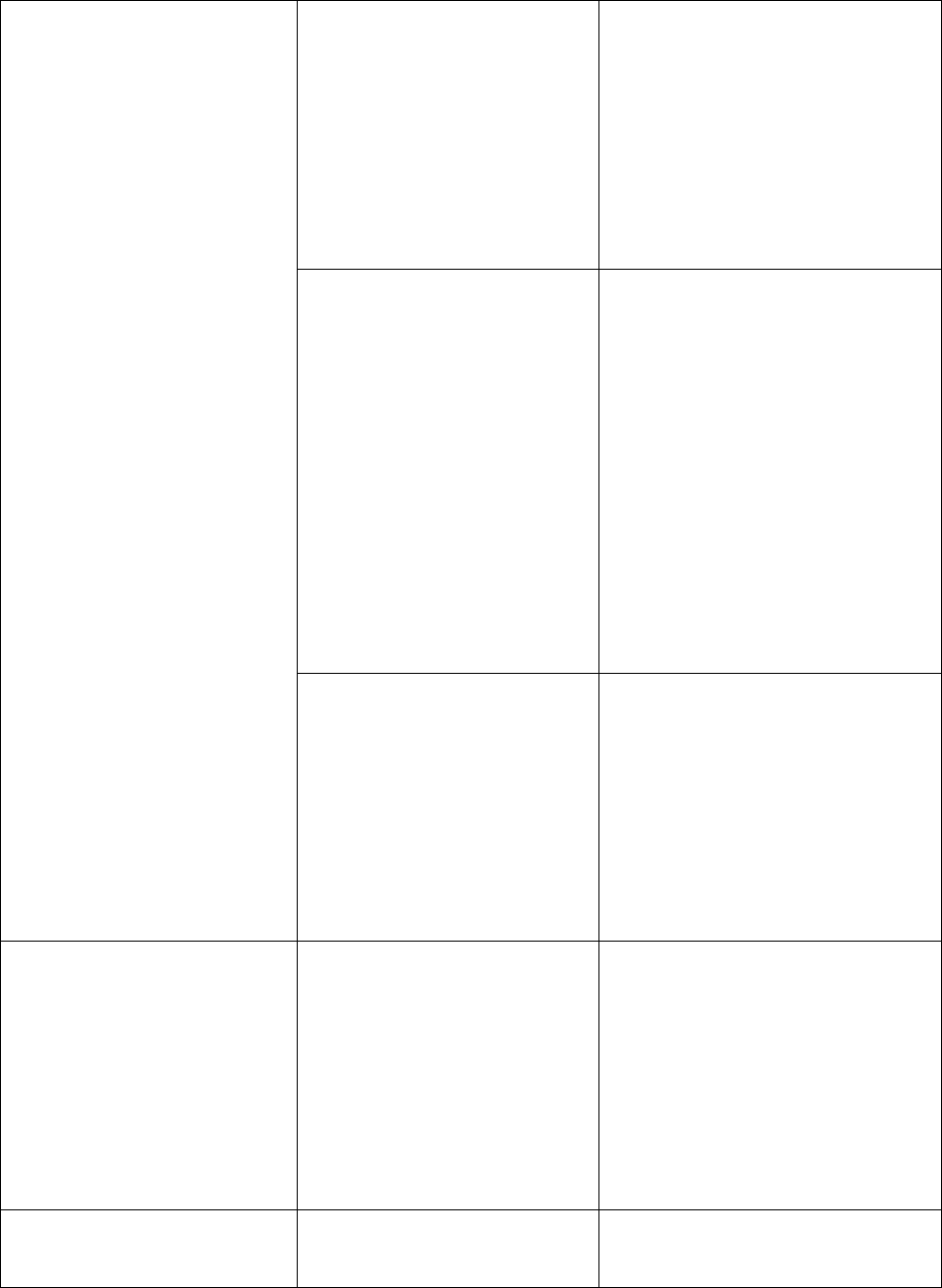

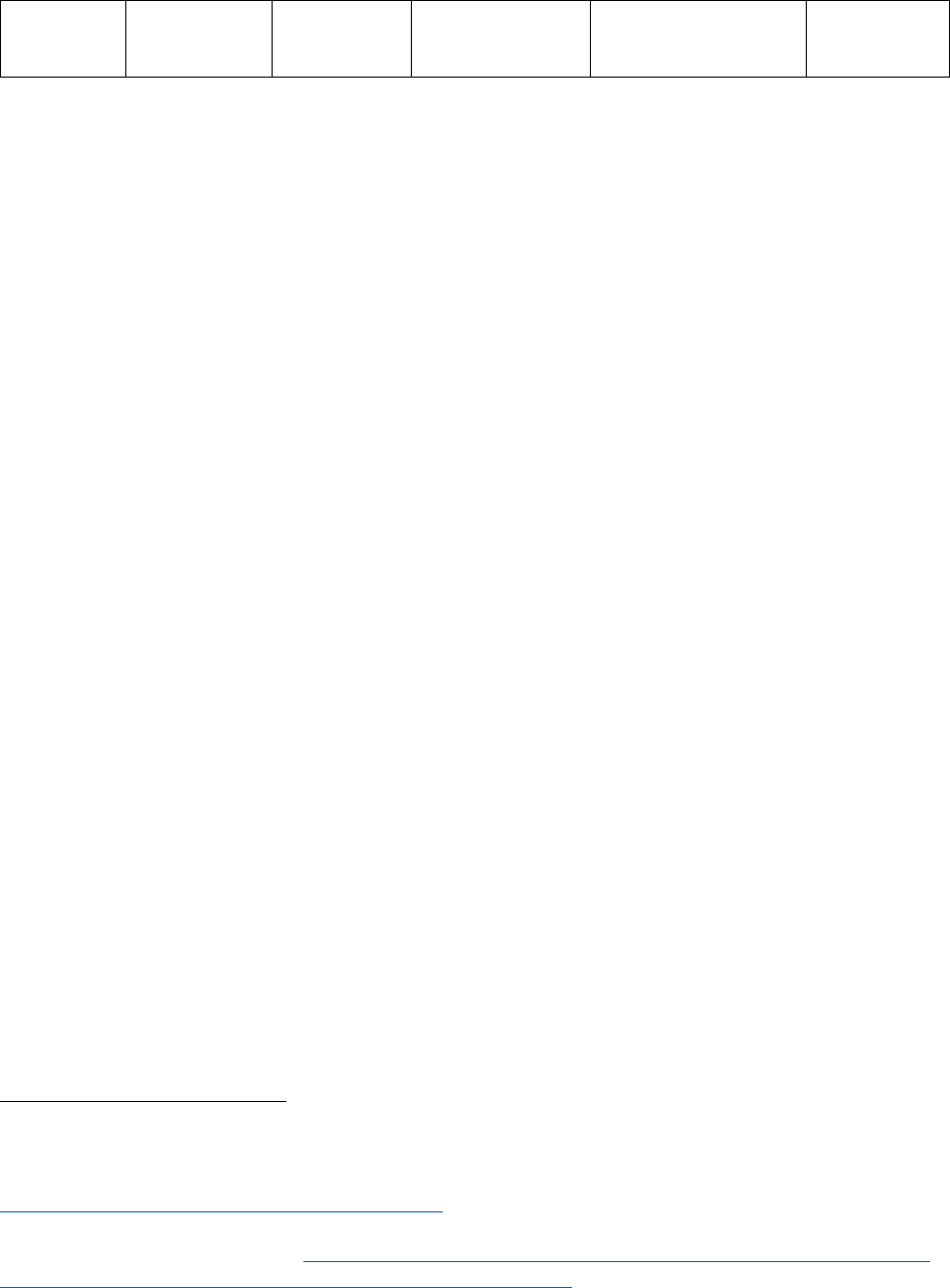

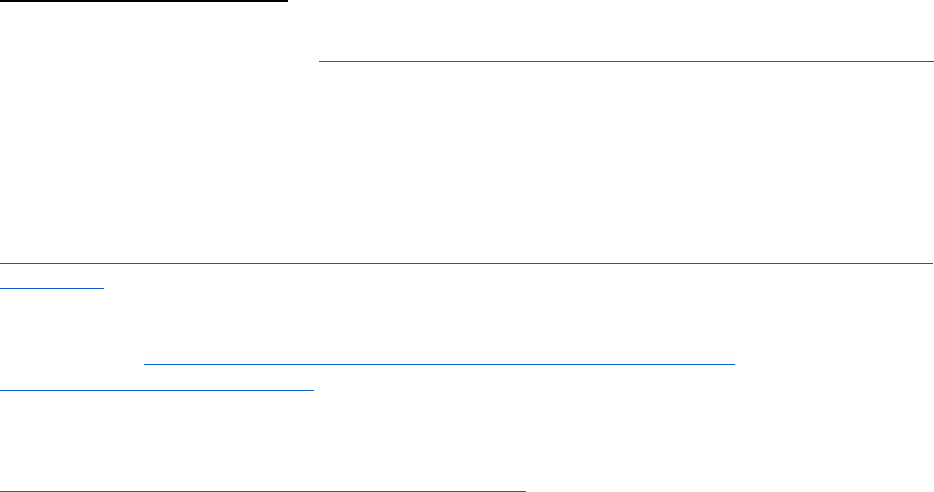

Table 1: Overview of Principal Federal Labor and Employment Laws and Enforcing Agencies

AGENCY

LAWS ENFORCED

EXAMPLES OF

VIOLATIONS

TYPICAL STATUTE

OF LIMITATIONS

COMPLAINT

PROCESS

National Labor

Relations

Board (NLRB)

National Labor

Relations Act

• Right to

unionize

• Right to

organize and

engage in

“protected

concerted activity,”

free of retaliation

An employer cuts a

worker’s hours for

talking to co-workers

about poor working

conditions.

An employer fires a

worker for

supporting the union.

6 months

https://www.nlrb.g

ov/

guidance/fillable-

forms

USDOL Wage

and Hour

Division

(WHD)

Fair Labor

Standards Act

(FLSA)

• Minimum wage

• Overtime

• Child labor

• Retaliation

Workers work over

40 hours in a

workweek but do not

receive overtime

pay.

2 years (3 years for

willful violations)

https://www.dol.g

ov

/agencies/whd/

contact/complaints

Family Medical

Leave Act

• Unpaid, job-

protected leave for

certain family and

medical needs

A new parent is fired

for requesting 12

weeks off to care for

their newborn.

2 years (3 years for

willful violations)

https://www.dol.g

ov

/agencies/whd/

contact/complaints

Labor standards

protections of H-2A,

H-2B, and H-1B

programs

• Wage, housing,

transportation, and

disclosure standards

An employer pays

their H-2A

agricultural workers

by piece rate, and the

resulting wage is

below the local

prevailing wage for

U.S. workers in the

same occupation.

Best to file as soon

as possible, and

within 2 years,

because of legal

ambiguity on the

statute of

limitations

https://www.dol.g

ov

/agencies/whd/

contact/complaints

24

For example, the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) applies only to employees who: (1) are involved in

interstate commerce; (2) work for a business that has at least two employees and does an annual business

of at least $500,000; or (3) work for hospitals or certain businesses providing medical or nursing care.

U.S. Dep’t of Labor, Fact Sheet #14: Coverage Under the Fair Labor Standards Act (July 2009),

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fact-sheets/14-flsa-coverage.

9

USDOL

Occupational

Safety and

Health

Administration

(OSHA)

Occupational Safety

and Health Act

• Health and

safety standards

• Whistleblower

protections

A construction

worksite fails to

provide proper fall

protection training.

An employer gives a

worker a less

favorable job

assignment because

they filed an OSHA

complaint.

6 months for health

and safety

violations

30-180 days for

whistleblower

violations,

depending on type

of violation

https://www.osha.

gov/

workers/file-

complaint

USDOL Office

of Federal

Contract

Compliance

Programs

(OFCCP)

Executive Order

11246 and other

anti-discrimination

laws and regulations

applicable to federal

contractors and

subcontractors

• Prohibiting

discrimination based

on race, color, sex,

sexual orientation,

gender identity,

religion, national

origin, or veteran

status

• Prohibiting

retaliation for

inquiring about or

disclosing

compensation

Note that OFCCP

refers complaints

alleging individual

discrimination based

on race, color,

religion, sex, or

national origin to

EEOC.

A business with

federal government

contracts fires a

worker for talking

with co-workers

about how much she

is paid.

A business with

federal government

contracts

discriminates against

workers based on

sexual orientation.

180 days for

discrimination

based on race,

color, religion, sex,

sexual orientation,

gender identity,

national origin, or

compensation

inquiries/disclosure

300 days for

discrimination

based on disability

or protected veteran

status

https://www.dol.g

ov/agencies/ofccp/

contact/file-

complaint

10

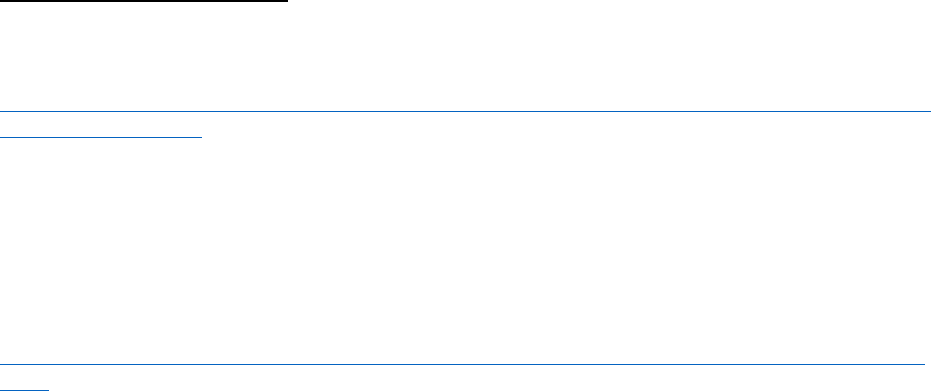

Equal

Employment

Opportunity

Commission

(EEOC)

Federal Anti-

Discrimination Laws

(inc. Title VII and

the ADA)

• Prohibiting

discrimination based

on race, color,

religion, sex, gender

identity, sexual

orientation, national

origin, age, or

disability

An employer uses

racial slurs, creating

a hostile work

environment.

180 or 300 days

depending on

state/locality

https://www.eeoc

.gov/

filing-charge-

discrimination

2. Obtaining a Labor or Employment Agency Statement of Interest

a) What is a Labor or Employment Agency Statement of Interest?

A labor or employment agency Statement of Interest is a written request from a federal, state, or

local labor or employment agency “asking DHS to consider exercising its discretion on behalf of

workers employed by companies identified by the agency as having labor disputes related to

laws that fall under its jurisdiction.”

25

Importantly, Statements of Interest generally identify a

workplace or employer, rather than specific worker(s). A Statement of Interest typically asks

DHS to use its discretion to protect workers who are or were employed at a particular worksite(s)

or by a particular employer during a time relevant to an agency investigation (and who are

therefore potential victims or witnesses). For example:

Example 1: The EEOC is investigating charges from several workers that, from

November 2021 through the present, their employer subjected them to harassment due to

their race and national origin. The EEOC issues a Statement of Interest requesting a

favorable exercise of prosecutorial discretion for workers employed by the employer at

any time from November 2021 through the present.

Example 2: DOL’s Wage and Hour Division is investigating violations of the Fair Labor

Standards Act’s minimum wage and overtime provisions by a company with worksites

throughout the state of Ohio. DOL issues a Statement of Interest requesting a favorable

exercise of prosecutorial discretion for workers employed by the company at any

worksite in Ohio over the past three years.

Example 3: The NLRB is investigating unfair labor practice charges filed by several

employees. The NLRB issues a Statement of Interest requesting a favorable exercise of

prosecutorial discretion for workers employed by the employer from January 2021

through the present, the time-period during which the employer allegedly engaged in the

unlawful practices.

25

See DHS Announcement, supra note 2.

11

Redacted Statements of Interest from each federal labor agency are available by request only in

Appendix 4.

Practitioners should note that Labor-Based Deferred Action does not currently provide any

means for family members to receive deferred action as derivatives of the principal beneficiary.

In the vast majority of cases so far, Statements of Interest covered only workers, not family

members.

26

b) How to Obtain a Statement of Interest

Labor and employment agency processes to request Statements of Interest vary.

To request a Statement of Interest from the NLRB, workers or their advocates or representatives

should send a written request to the Board Agent assigned to their case, the Regional Director,

and the Immigration Coordinator (if known).

27

To request a Statement of Interest from the U.S. DOL (including the Wage and Hour Division,

the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and the Office of Federal Contract

Compliance Programs), workers or their advocates or representatives should send an email to

state[email protected] describing: (1) “the labor dispute and how it is related to the laws

enforced by DOL;” (2) related retaliation the workers witnessed or experienced, if any; and (3)

how the chilling effect of potential immigration consequences may deter workers from reporting

violations or otherwise cooperating with DOL. Note that while workers should include

information about retaliation where applicable, there is no requirement that worker have

witnessed or experienced retaliation in order to qualify for a Statement of Interest. DOL’s

Frequently Asked Questions provides further details and requirements.

28

To request a Statement of Interest from the EEOC, workers or their advocates or representatives

should contact the District Director and Regional Attorney at their local EEOC Field Office.

Requests should: (1) “[I]dentify the workplace involved in the relevant EEOC investigation or

litigation;” (2) provide “information about retaliation, whether immigration-related or otherwise,

or fear of such retaliation, that is likely to deter employees from reporting to the EEOC or

26

The only exception was in a case involving deceased workers whose family members were potential

witnesses in the agency investigation. There is a strong argument that labor and employment agencies

should issue Statements of Interest covering workers’ family members whenever needed for workers to

feel safe reporting violations, participating in agency investigations, or otherwise exercising their labor

rights. The DOL appears to acknowledge this by recognizing that “undocumented workers who

experience labor law violations may fear that cooperating with an investigation will result in the

disclosure of their immigration status or that of family members, or that it will result in immigration-based

retaliation from their employers and adverse immigration consequences for themselves or their family.”

DOL FAQ, supra note 18 (emphasis added).

27

See Jennifer A. Abruzzo, Gen. Counsel, Nat’l Labor Relations Bd., Ensuring Rights and Remedies for

Immigrant Workers under the NLRA, Memo 22-01, (Nov. 8, 2021),

https://apps.nlrb.gov/link/document.aspx/09031d45835cbb0c; Joan Sullivan, Assoc. Gen. Counsel, Nat’l

Labor Relations Bd., Ensuring Safe and Dignified Access for Immigrant Workers to NLRB Processes,

OM 22-09 (May 2, 2022), https://apps.nlrb.gov/link/document.aspx/09031d458375a553.

28

See DOL FAQ, supra note 18.

12

participating in its investigations or litigation;” and (3) include the Requestor’s contact

information.

29

The EEOC’s Frequently Asked Questions provide further details and

requirements.

30

A template Statement of Interest request is included in Appendix 2. Note that the request need

not name specific workers and should not disclose any worker’s immigration status or contain

sensitive personally identifiable information. The request should, however, frame the time period

relevant to the labor or employment law violation, worksite(s), and employer(s) as broadly as

possible to cover all current and former employees who could potentially be victims of, or

witnesses to, the violation. Specifically, the request should list all relevant employers (including

any possible joint employers and subcontractors), all relevant worksites, and the relevant time

period (including the earliest date of evidence of a labor violation through the filing of the

agency complaint and anticipated further proceedings, including compliance and monitoring).

These details will define the scope of workers who are eligible to file for Labor-Based Deferred

Action, and so the request is a key opportunity to ask for the class of affected workers to be as

broad as possible. If the agency may be inclined to limit the scope of the Statement of Interest in

any way that might exclude potential witnesses, the request should explicitly address why the

Statement of Interest should be broad to prevent or counteract retaliation and facilitate the

participation of all potential witnesses.

As of the publication of this Practice Manual, no state and or local labor or employment agency

has yet published guidance for seeking a Statement of Interest. The absence of published

guidance does not mean an agency will not issue a Statement of Interest. In fact, a number of

state labor agencies have already issued Statements of Interest. A worker seeking a Statement of

Interest from a labor or employment agency without published guidance should contact the

agency to ask how it wishes to receive Statement of Interest requests. They may also wish to put

the agency in touch with DHS. DHS has indicated that labor and employment agencies seeking

more information about Statements of Interest and Labor-Based Deferred Action may contact

laborenforceme[email protected].

When a labor or employment agency decides to issue a Statement of Interest, it will submit the

Statement to DHS and allow DHS up to three days to review before distributing to the

requestor.

31

If the labor or employment agency decides not to issue a Statement of Interest, then

the agency should not communicate with DHS about that request.

32

c) A Note on Worker Organizing and Information Sharing

Practitioners representing workers applying for Labor-Based Deferred Action should be aware

that workers may have invested (or be prepared to invest) significant effort and courage,

potentially as part of collective organizing efforts, in coming forward to report labor and

employment law violations. Particularly where Statements of Interest cover many workers,

practitioners may be asked to coordinate with unions, workers centers, and other advocates and

29

See EEOC FAQ, supra note 22, at Q5.

30

Id.

31

DHS FAQ, supra note 3.

32

See DOL FAQ, supra note 18, at Q11; EEOC FAQ supra note 22, at Q7.

13

organizers in assisting workers applying for Labor-Based Deferred Action. Practitioners are

encouraged to see Labor-Based Deferred Action as an opportunity not only to assist individual

workers, but also to contribute to a larger effort, decades in the making, to build power for

immigrant workers, including via the powerful DALE campaign.

33

Labor and employment

attorneys, non-attorney advocates, and organizers may be instrumental in the labor agency

process and can serve as important resources for the immigration practitioner. Workers may have

longstanding relationships of trust with these advocates and may seek their support in making

significant decisions and navigating the process of seeking Labor-Based Deferred Action.

Because of these considerations, practitioners should discuss with each worker their preferences

for sharing information with other advocates working on the matter, making sure to explain all

relevant confidentiality considerations, and respect the worker’s preferences.

C. Screening & Counseling for Labor-Based Deferred Action

Once a Statement of Interest has been, or is likely to be, issued, the next step is for an

immigration practitioner to conduct a thorough screening.

1. Immigration Screening Interview

As with any other client seeking an immigration benefit, it is critical to individually assess the

worker’s complete history to evaluate their eligibility for Labor-Based Deferred Action and other

forms of immigration relief, and to consider the prospects of success as well as any risks in

applying. Workers may have questions about deferred action or other immigration paths and they

should have the opportunity to receive counseling tailored to their case.

Through the intake, practitioners should assess:

1) whether the noncitizen falls within the scope of the Labor Agency Statement of

Interest (i.e., whether the worker worked at the covered worksite(s) and/or for the

covered employer(s) during the covered time period);

2) complete immigration history, as relevant to equities for discretion, and whether

USCIS or ICE would have jurisdiction to adjudicate deferred action;

3) criminal history, as relevant to equities for discretion;

4) biographic information and family ties; and

5) ability to pay the Employment Authorization application fee or eligibility for a fee

waiver.

Although a standard immigration intake form, such as the example provided by ILRC, will

generally suffice,

34

a form tailored to this Labor-Based Deferred Action process is available in

Appendix 3, which aims to gather all the information needed to fill out the forms required for

this process (including a fee waiver, if needed). As detailed in the chart below, the information

33

See Nat’l Day Laborer Organizing Network, DALE: Desde Abajo Labor Enforcement,

https://ndlon.org/dale-campaign/ (last visited Mar. 10, 2023).

34

Immig. Legal Res. Ctr., Sample Client Intake Form,

https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default/files/resources/ilrc_sample_intake_form_-_sept_2019_0.pdf (last

updated Sep. 2019).

14

gathered in the interview (especially with regard to criminal or immigration history) can inform

whether the practitioner will advise the client to file record requests before proceeding to apply

for deferred action. These are the key areas where practitioners should screen workers in order to

advise on Labor-Based Deferred Action eligibility, flag any issues that may complicate the case

or pose risks, and identify other potential forms of relief (each of which is discussed in greater

detail in subsequent sections).

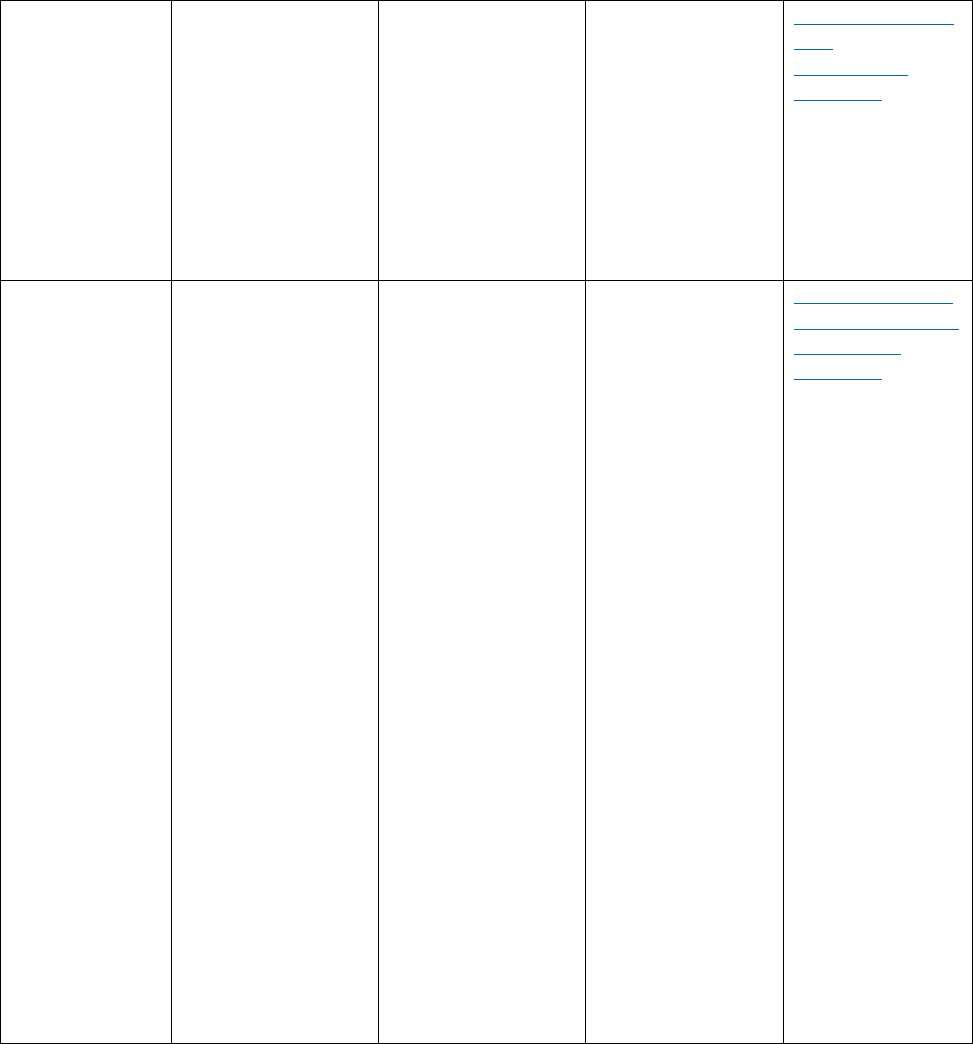

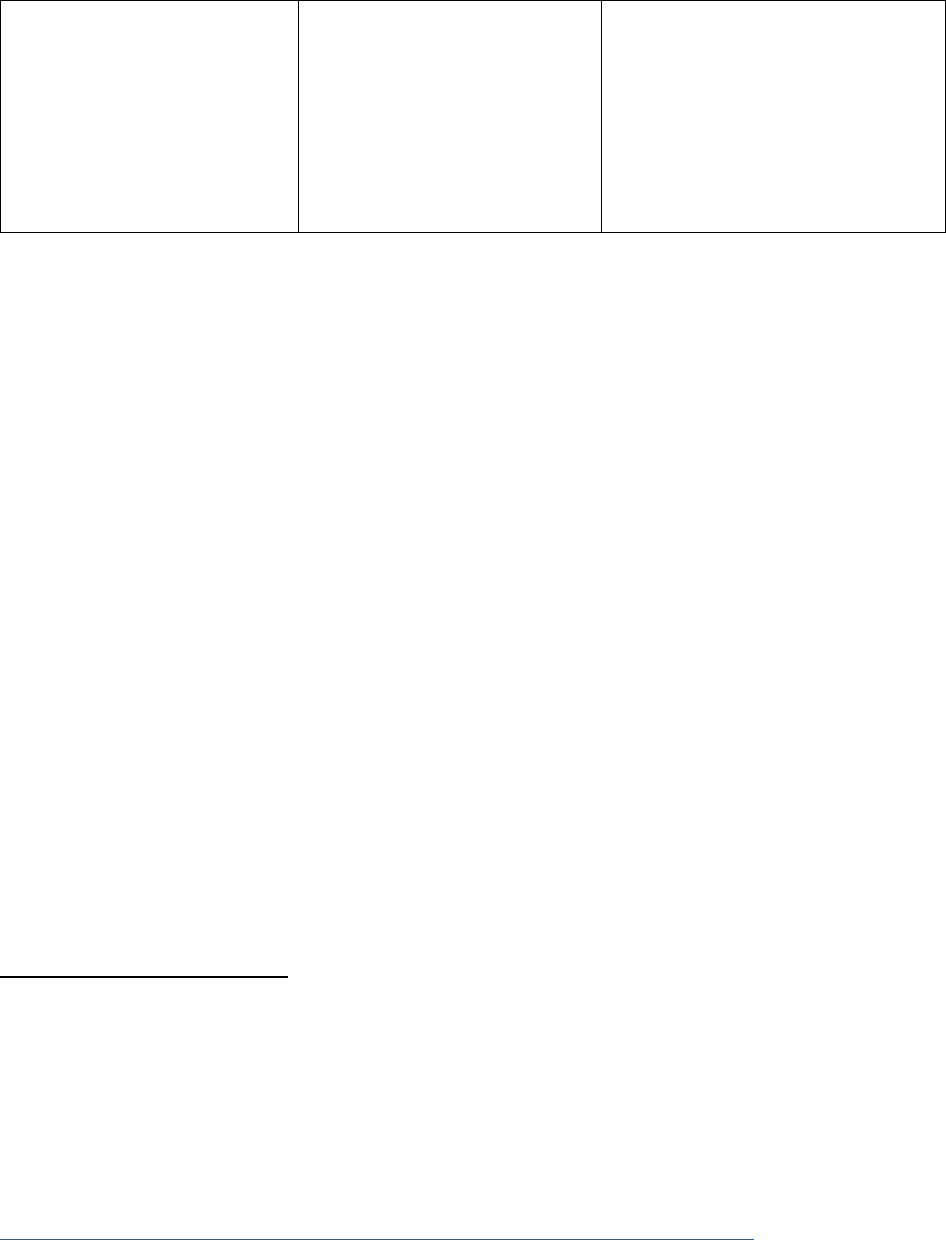

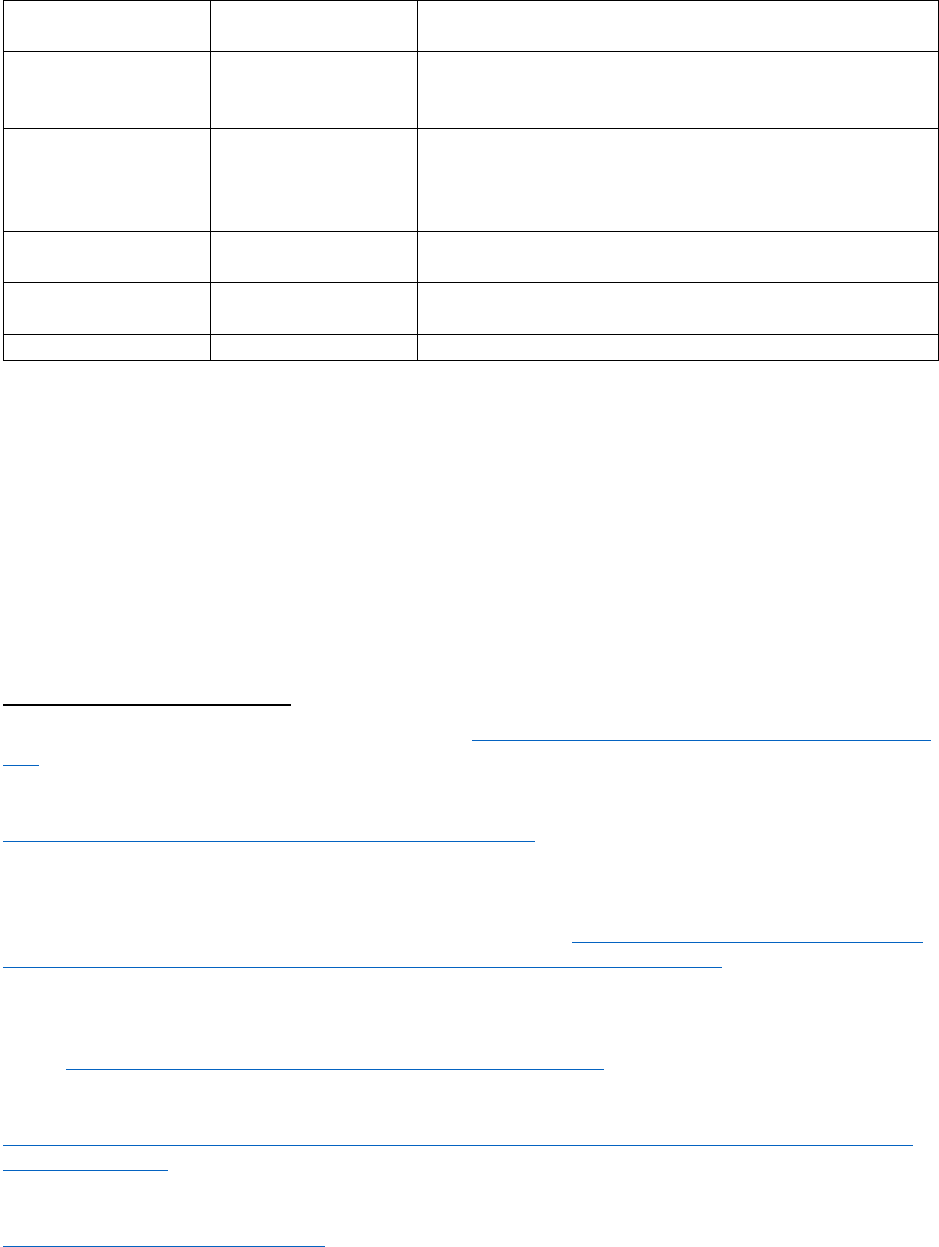

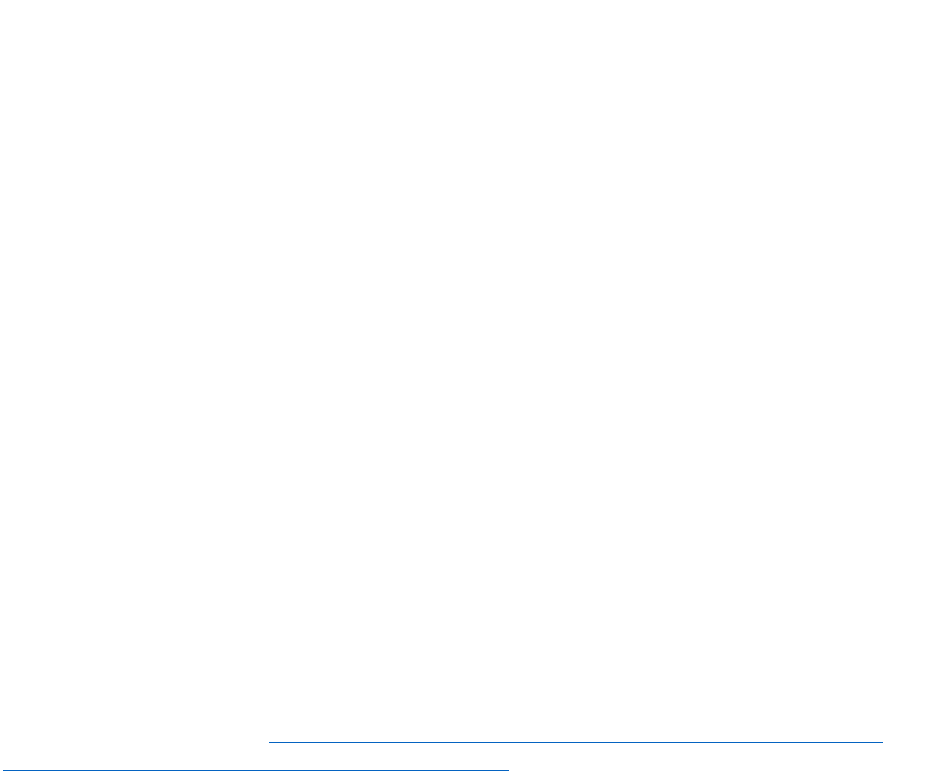

Table 2: Immigration Screening Criteria for Labor-Based Deferred Action

ISSUE

RELEVANCE TO THIS PROCESS

CONSIDERATIONS FOR

COUNSELING & CASE STRATEGY

Immigration

History

• The new guidance states that in cases

where workers are in removal proceedings

or have prior orders of removal, USCIS

will “forward” their applications to ICE for

review. It is not yet known if the ICE

forwarding processing will cause delays in

adjudication.

• As a discretionary form of relief, USCIS

may deny deferred action based on

negative immigration history. Therefore,

negative history may require additional

evidence of positive equities to support the

worker’s application. See infra Part II

Section E.1.

• Advocates should consider filing a FOIA

for prior immigration records, or FBI/State

background check to adequately assess risk.

• Advocates should advise client about

information being shared with ICE if

application will be forwarded to ICE for

review.

• Advocates should counsel clients about

risks of applying and need for positive

equities evidence if there is substantial

negative immigration history (including

multiple removals or re-entries, or prior

denials of affirmative applications). Workers

in removal proceedings or with prior removal

orders may need to separately request

prosecutorial discretion from OPLA to

terminate (or reopen and terminate

proceedings).

Criminal

History

• Although there is no specific criminal

bar to applying for Labor-Based Deferred

Action, criminal history that is undisclosed

in the initial request may result in a

Request for Evidence (RFE). The

immigration agencies may also request

additional records for even disclosed

history through RFEs.

• As a discretionary form of relief, USCIS

may deny deferred action based on

negative criminal history. Therefore,

negative history may require additional

evidence of positive equities to support the

worker’s application and should prompt

practitioners to engage in a thorough

assessment of application risks. See infra

Part II Section E.1.

• Advocates should request records from the

jurisdiction of conviction and/or a state or

FBI background check.

• Advocates should advise workers,

depending on their individual criminal

history, about the possibility of a denial, as

well as whether they are generally

removable—apart from this application—

because of their criminal history.

• Advocates should affirmatively submit

criminal dispositions with additional

evidence of positive equities.

Other

Immigration

Relief

• Workers should receive a full

immigration screening, both to determine

• Workers can apply for both Labor-Based

Deferred Action and U/T visa, either at the

15

U/T visa eligibility arising from the labor

dispute,

35

as well as any other forms of

immigration relief that may provide a

viable path to permanent status.

• Workers who have qualifying U.S.

citizen relatives (or are Cuban nationals)

may wish to apply for parole in place to be

eligible to adjust status if the worker

previously entered without inspection. See

infra Part IV Section B for a discussion of

applying for parole in place in labor cases.

same time or in sequence. Practitioners

should advise workers on other potential

benefits stemming from these visa programs,

such as Continued Presence (for victims of

trafficking) and Bona Fide Determination/4-

year Deferred Action status for U visa

applicants. See infra Part IV, Section D.

• The new guidance offers no specific

process for applying for parole in place in

labor cases. Consequently, parole in place

applications will be filed at local USCIS field

offices and may be subject to existing

backlogs and/or to additional filing

requirements and fees. See infra Part IV

Section B. Thus, advocates should advise

workers of the greater uncertainty of filing

for parole in place.

2. Understanding Immigration and Criminal History—FOIAs & Other Record Requests

Depending on what a worker discloses in their screening interview, practitioners should submit

FOIA or other record requests to various government agencies to review any negative

immigration and criminal history. Depending on the agency or sub-agency, responses to these

record requests vary from 30 days to many months. FOIA requests to USCIS’s National Records

Center for the A File currently have short processing times, and the A File should generally

contain most relevant immigration history. Practitioners should weigh the potential delay as well

as potential uncertainty of any negative immigration or criminal history based on what worker

discloses during the screening interview and then discuss any risks with the worker so they can

make an informed decision to either proceed with filing or wait for records. Table 3 below offers

guidance on when to request certain records and what to expect to receive from each agency.

36

35

See infra Part IV Section D.

36

For detailed instructions how to file FOIA requests to DHS sub-agencies, see Immig. Legal Res. Ctr., A

Step-by-Step Guide to Completing FOIA Requests with DHS (Dec. 2021),

https://www.ilrc.org/sites/default/files/resources/new_foia_dhs_practice_advisory_-_2021.pdf.

16

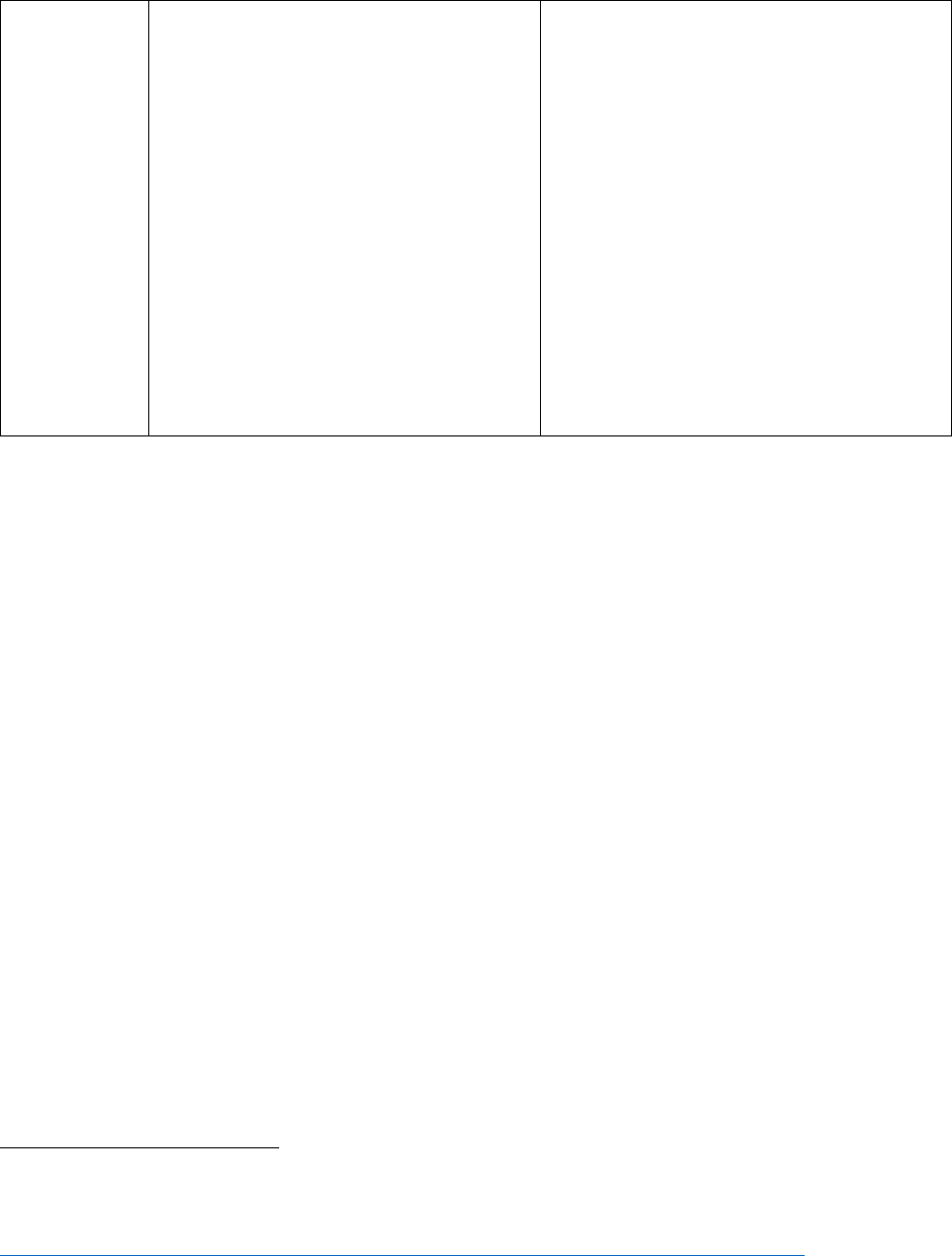

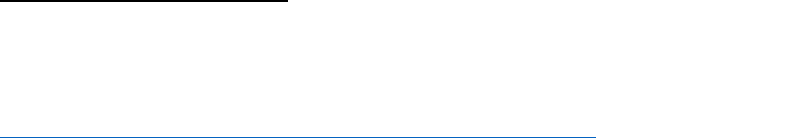

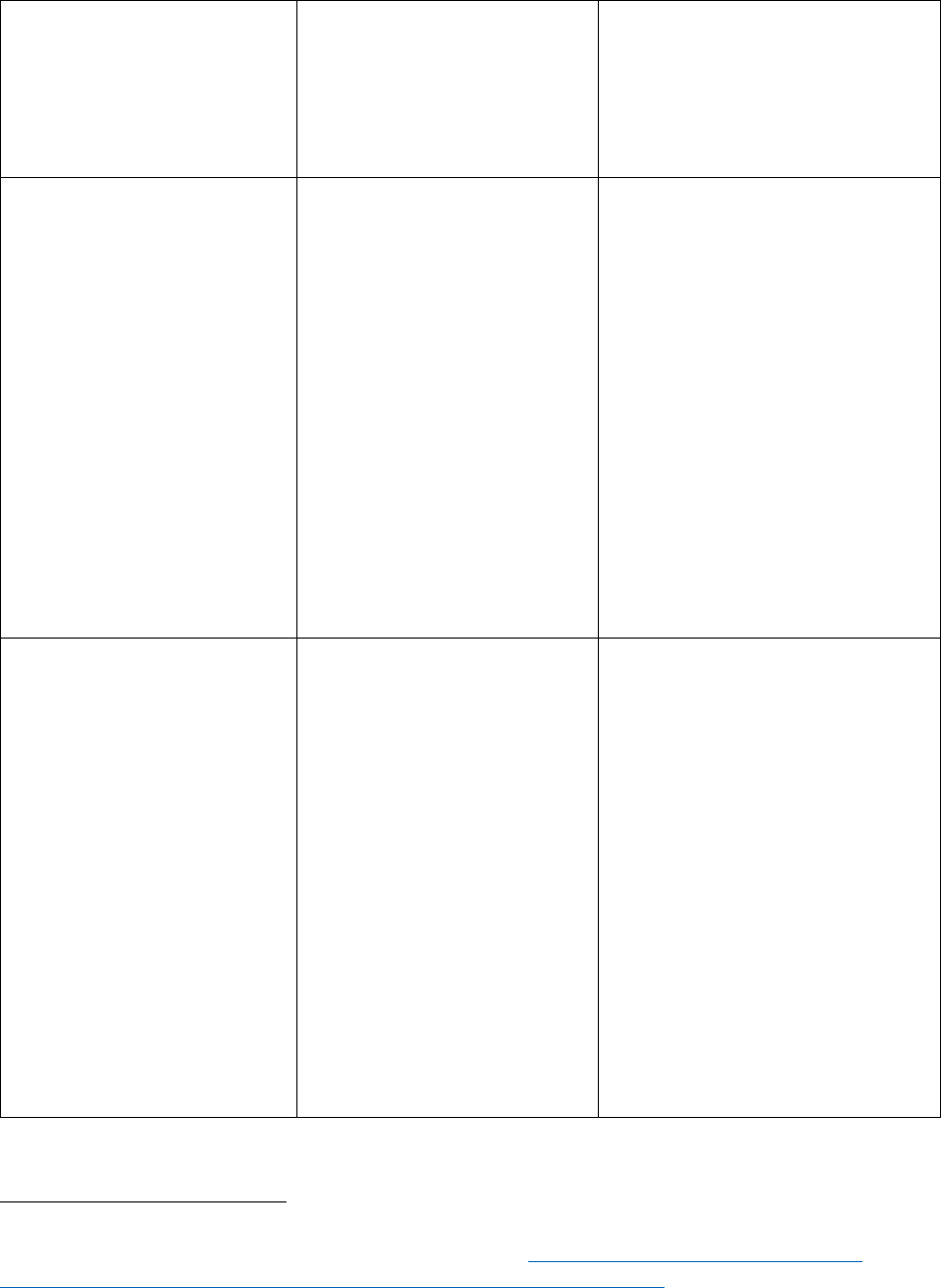

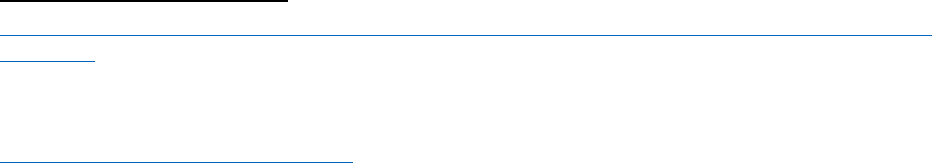

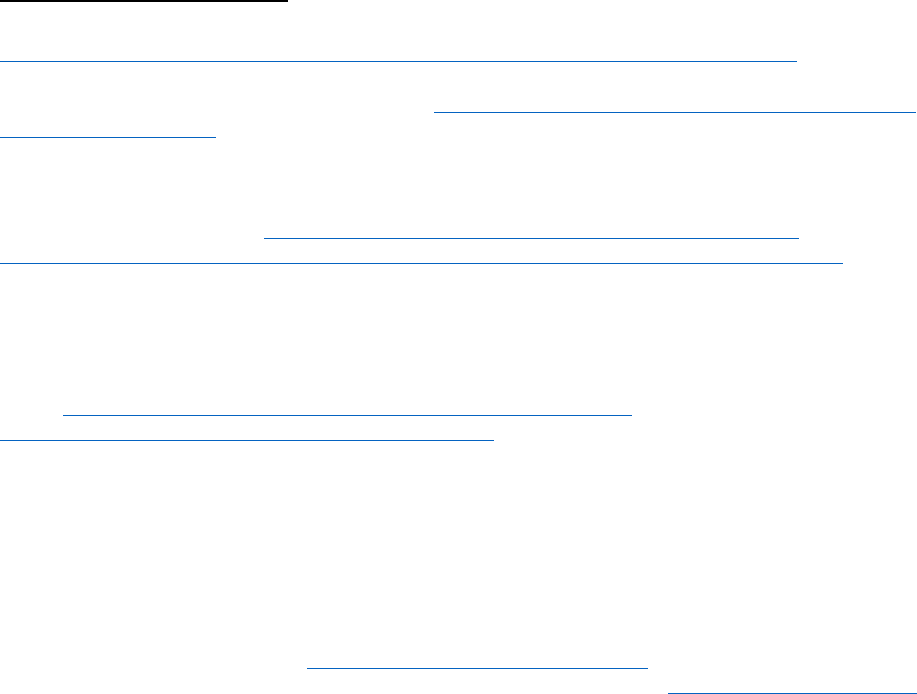

Table 3: Records Requests

RECORDS

TYPE

AGENCY

CONSIDER FILING IF…

RESULTS

Immigration

History

37

USCIS

… worker reports any prior immigration

history that suggests they may have a

removal order, even if they never went to

court, and/or interaction with border

officials.

This request should provide

the worker’s “A-File”

containing some but not all

records of immigration

history. A-File requests are

currently processed in

approximately 30 business

days if filed online.

38

CBP

39

… worker reports any interactions with

border agents, “border police,” etc. as

they entered the U.S. that may have

resulted in a removal order including

“turn backs” and/or voluntary returns.

This request should reveal

any border arrests, border

interrogations, entries/exits,

and expedited orders of

removal issued by Customs

& Border Protection.

EOIR

… worker reports receiving a Notice to

Appear in immigration and/or appearing

before immigration court. If the client

was detained at the border and released

with paperwork, they may have a

removal or deportation proceeding

before immigration court.

40

This file should contain all

records from removal

proceedings in immigration

court.

37

If the client does not have an A-number, be sure to include all spellings and versions (including past

misspellings) of a worker’s name to better ensure all their records are located in requests to immigration

agencies.

38

For more information on FOIA requests for A-files, see Nat’l Immig. Litig. All., Am. Immig. Council,

Nw. Immig. Rts. Project, and Law Offs. of Stacy Tolchin, Nightingale v. USCIS and FOIA Requests for

Immigration Case Files (A-Files) (Jan. 18, 2023),

https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/sites/default/files/practice_advisory/nightingale_foia_advis

ory_updated.pdf.

39

Practitioners can also file a FOIA request to OBIM in conjunction with a request to CBP. OBIM

requests will return records of any biometrics taken pursuant to a border arrest. See ILRC guide, supra

note 36.

40

Practitioners should probe whether the worker ever received a 9-digit A-number. Many individuals are

not aware they received one but may have paperwork from being processed at the border or a Notice to

Appear—either of which will include the A-number. With an A-numbuther, practitioners can easily use

EOIR’s online case portal to confirm whether the worker is in removal proceedings or has a final order of

removal (including in absentia order, but not expedited removal orders). A-Numbers may be searched on

Executive Office of Immigration Review (EOIR), Automated Case Information,

https://acis.eoir.justice.gov/en/ (last visited Mar. 10, 2023).

17

Criminal

History

FBI

Background

Check

… worker reports arrest(s) or

conviction(s), federal charges, and/or

does not know the jurisdiction of

conviction to request them directly.

Practitioners should inquire about

various scenarios including traffic stops,

being handcuffed, or taken to a police

station, and/or appearing before a judge.

This report should include

state and federal arrests and

convictions, including

border arrests (though is

often incomplete). This

requires submitting

fingerprints in addition to a

form, which can be filed

online and are typically

processed faster than

FOIAs. FBI reports also

frequently contain

information on border

arrests.

41

State/County

Records

… worker reports prior criminal history

and knows the local jurisdiction where

the arrest or conviction occurred,

including traffic violations.

These records should

include arrest and court

records including final

dispositions.

42

3. Counseling

a) Benefits of Approval, Prospects of Success, and Limitations of

Temporary Status

Practitioners should review with workers the benefits of deferred action, including work

authorization, a Social Security number, access to apply for state identification or a driver’s

license, and the tolling of unlawful presence, as described in more detail above, see Part II

Section A.

Practitioners should also note that, although DHS should show deference to the labor agency’s

enforcement interest and statement of interest in the case, the agency will still use its discretion

to balance individual positive and negative equities. Accordingly, workers with significant

negative immigration or criminal history may receive requests for more evidence, or even denial,

even with the significant positive equity of their involvement in the labor dispute. In some of the

early cases—processed in various USCIS Field Offices without the benefit of trained, specialized

adjudicators—workers with some negative criminal or immigration history were approved for

deferred action. Practitioners should assess and advise each client based on the equities of their

individual case.

41

Fed. Bureau of Investigations, FBI: How Can We Help You, Identity history Summary Checks,

https://www.fbi.gov/how-we-can-help-you/more-fbi-services-and-information/identity-history-summary-

checks (last visited Mar. 10, 2023).

42

Every state has a law that mirrors FOIA, often referred to as Public or Open Records Requests or other

names. If the county of conviction is known, there may be an online system to request criminal records.

Practitioners may want to consult local criminal defense attorneys or public defender’s officers, where

they exist, for help in quickly locating state or country criminal records and deciphering them.

18

b) Sharing Information and Possible Future Immigration Enforcement

Practitioners should counsel each individual client on the risks of providing their personal

information to DHS through an application for Labor-Based Deferred Action according to the

specific facts of their case.

DHS has not made any formal guarantee that information in an application for Labor-Based

Deferred Action will not be used against a worker in a future proceeding or action. However,

current USCIS Guidance on the Referral of Cases and Issuance of Notices to Appear provides

that USCIS will refer denied cases to ICE for the purpose of initiating removal proceedings only

under limited circumstances, including in cases involving substantiated fraud, “egregious public

safety” cases involving arrests or convictions for certain enumerated offenses, or national

security cases.

43

It is important to be familiar with this guidance in order to advise workers

whether they are currently at risk of being referred for removal if their applications are denied. It

is also important to note, however, that agency guidance could change, especially in the event of

an administration that harbors an anti-immigrant sentiment.

Practitioners should advise workers who are in removal proceedings or have final removal orders

that their applications will be adjudicated by ICE, rather than USCIS, which may entail different

risks. USCIS has provided a centralized filing location, regardless of workers’ current

immigration status. However, where USCIS determines that an applicant is in removal

proceedings or has a final removal order, USCIS will “forward” the request to ICE for

adjudication.

44

It is our understanding that Homeland Security Investigation’s Parole and Law

Enforcement Programs Unit (HSI PLEPU) unit will adjudicate these cases, in consultation with

the relevant ERO and OPLA offices. Practitioners should consider whether ICE already has

access to a worker’s current address and personal information in assessing the risk of providing

that information via a Labor-Based Deferred Action Application. Practitioners should explain the

involvement of ICE and its subagencies in these cases so that clients can make an informed

decision to proceed or not in submitting an application. Practitioners should also note that it is

unclear what legal standard ICE will apply in determining whether to pursue enforcement against

those who are denied deferred action.

45

43

Policy Memorandum, U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs, Revised Guidance for the Referral of Cases

and Issuance of Notices to Appear (NTAs) in Cases Involving Inadmissible and Removable Aliens, PM-

602-0050 (Nov. 7, 2011),

https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/memos/NTA%20PM%20%28Approved%20as%20fin

al%2011-7-11%29.pdf.

44

See DHS FAQ, supra note 3 (“USCIS and ICE, as appropriate, will consider and make a case-by-case

determination of the deferred action request and USCIS will consider all related Forms I-765, if

submitted.”).

45

Because the September 30, 2021 Mayorkas general priorities memo remains under litigation, see

Appendix 1, individual ICE officials currently have wide discretion in enforcement decisions. DHS

officials have attempted to reassure that ICE officials should make decisions “in a way that best protects

against the greatest threats to the homeland.” Ellen M. Gillmer, Immigrant Arrests Targets Left to

Officers With Biden Memo Nixed, BLOOMBERG LAW (Jul. 26, 2022),

https://news.bloomberglaw.com/immigration/immigrant-arrest-targets-left-to-officers-with-biden-memo-

nixed.

19

c) Fears of Employer Retaliation

Neither USCIS nor ICE will contact an applicant’s employer when adjudicating an application

for Labor-Based Deferred Action. If an employer learns that a worker is seeking immigration

protection from another source, such as from another worker or a news article discussing the

case, it is unlikely that the employer will be able to gain access to the Labor-Based Deferred

Action application via a FOIA request.

46

Some labor rights advocates have expressed concern that an employer could use a worker’s

request for immigration relief against them if there is litigation of their labor case, such as when

the employer contests the labor agency’s fines and/or if worker files a private civil action against

the employer. For example, an employer may try to intimidate a worker by seeking aggressive

discovery into their requests for immigration relief or, in the rare cases that proceed to

depositions or trial, an employer may try to cast doubt on a worker’s testimony by suggesting the

worker is exaggerating or fabricating labor law violations to obtain immigration relief. In either

situation, there are potentially effective strategies to respond, including using standard strategies

to rehabilitate witness credibility, seeking a protective order against immigration-related

discovery, or filing motions in limine to exclude such evidence at trial.

47

Strategies will vary

depending on the type of case being investigated or litigated, and the role of the labor agency

involved. However, these strategies are not foolproof. In particular, the availability of protective

orders may vary across different jurisdictions, and employers may serve broad discovery

requests that encompass workers’ request for immigration relief even if employers were not

previously aware workers made such requests. Accordingly, in an abundance of caution,

practitioners should advise workers about the possibility their employer may try to obtain

information about their request for immigration relief and/or use that request to discredit them in

their labor case. Practitioners may also want to advise workers that keeping their requests for

immigration relief confidential will decrease the likelihood their employer will raise these

arguments in litigation, so that workers may make an informed decision about whether and with

whom to share the fact that they have applied for Labor-Based Deferred Action.

d) Fears of Criminal Consequences of Applying

Immigration practitioners should note that a range of state and federal laws prohibit the use of—

and sometimes specifically working under—false names or Social Security numbers, and that

negative immigration consequences could accrue from this practice.

48

Although disclosing “other

46

USCIS generally does not release records to third parties absent the subject’s consent unless the

requestor can show “there is no privacy interest in the records, or . . . there is a public interest in the

records that outweighs the subject’s privacy interests.” U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Form G-639,

Freedom of Information/Privacy Act Request, 8 (Nov. 3, 2022),

https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/forms/g-639.pdf. Applications for Labor-Based

Deferred Action may also be exempt from disclosure under FOIA Exemption 7.

47

See, e.g., Rivera v. Nibco, Inc., 364 F.3d 1057 (9th Cir. 2004).

48

It is a federal felony to use a false Social Security Number with the intent to deceive and obtain

something of value. See 42 U.S.C. 408(a)(7)(B). There is a circuit split on the immigration consequences

of this crime. Compare Munoz-Rivera v. Wilkinson, 986 F.3d 587 (5th Cir. 2021) (holding that conviction

for using a false SSN is a crime involving moral turpitude because it involves dishonesty) with Beltran-

20

names used” on immigration forms does not itself carry immigration or criminal consequences,

where possible applicants should seek to establish proof of employment during the period of the

labor dispute without using evidence that could expose them to criminal liability or immigration

consequences.

e) Counseling Clients on Paying Work Authorization Application Fee or

Seeking a Fee Waiver

There is no cost to request deferred action. However, the streamlined process for applying for

Labor-Based Deferred Action requires that workers simultaneously apply for employment

authorization. These streamlined applications must be accompanied by the appropriate fee for the

I-765 application or a fee waiver, Form I-912.

49

Without a fee waiver, the application costs $410

as of this writing.

50

The form to request a fee waiver is lengthy, and advocates report that USCIS

is generally exercising increased scrutiny of fee waiver applications. To be successful, an

applicant will often need to submit significant accompanying documentation, depending on the

grounds for their eligibility. While applicants who receive a means-tested benefit can generally

just submit proof of their eligibility, applicants seeking waiver of fees on the ground that their

income is at or below 150 percent of the Federal Poverty Guidelines will generally be expected

to produce tax returns, paystubs, and/or other documentation of their low income. As discussed

in the preceding section, practitioners should not submit evidence that could expose applicants to

criminal liability or immigration consequences (such as a paystub showing the use of a fake

Social Security number that could constitute identity fraud). Practitioners should counsel the

noncitizen on the time to fill out the fee waiver application and the expected supporting

documentation, as some applicants may choose to pay the application fee rather than delay filing

their application and still risk possible denial of the fee waiver, resulting in rejection and return

of the underlying application.

51

D. Preparing a Labor-Based Deferred Action Application

Once a worker who falls within the scope of an agency Statement of Interest has decided that

they would like to proceed with applying for Labor-Based Deferred Action, the practitioner can

assemble the full application packet. This section describes the components of the application

packet, including both the forms and evidence, in general. Specific strategies to address

significant negative equities are addressed in more detail in Part II Section E.1.

Tirado v. I.N.S., 213 F.3d 1179 (9th Cir. 2000) (holding that conviction under 42 U.S.C. 408(a)(7)(B) is

not a crime involving moral turpitude because legislative history of Section 408 shows Congress did not

believe using a false Social Security number to work constituted moral turpitude).

49

U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Form I-912, Instructions for Request for Fee Waiver (Sept. 3, 2021),

https://www.uscis.gov/sites/default/files/document/forms/i-912instr.pdf.

50

U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Form I-765, Application for Employment Authorization,

https://www.uscis.gov/i-765.

51

If the need to apply for work authorization is caused by an underlying labor violation, then the labor

agency (specifically the NLRB) may seek reimbursement of the filing fee from the employer through the

labor agency adjudication as part of a consequential damages award. Even in compelling cases that the

NLRB is pursuing zealously, that reimbursement will likely take months or years.

21

Practitioners preparing these cases should remember that the Statement of Interest is a significant

positive equity for the worker that speaks to the enforcement interests of a sister government

agency that is enforcing labor and employment law under its statutory mandate.

52

Therefore, in

uncomplicated cases, additional positive equities are not necessarily required. Practitioners

should also keep in mind that deferred action does not require a specific finding of substantial

abuse, as for U nonimmigrant status, nor does it require a finding of extreme hardship, as for T

nonimmigrant status or cancellation of removal. Finally, practitioners should consider that while

adjudicators for these applications have received some specialized training, they are still

immigration adjudicators who do not have the same expertise as labor agency officials in labor

and employment law. Therefore, practitioners should describe the labor agency proceeding in

accessible language, with reference to the Statement of Interest, but should refrain from either

briefing the merits or severity of the labor violation, a factor which is not at issue before the

adjudicator, or submitting voluminous labor agency records that will be difficult for an

immigration adjudicator to decipher. Rather, practitioners should argue and present evidence that

shows that the worker falls within the scope of the Statement of Interest.

In early Labor-Based Deferred Action cases—processed in various USCIS Field Offices that did

not have the benefit of trained, specialized adjudicators—many workers with uncomplicated

cases were approved without a declaration from the worker, without community support letters,

and without evidence documenting individual harm or hardship from the labor violation.

53

1. Contents of Deferred Action and Employment Authorization Packet

The newly announced guidance includes a short list of requirements for a request for Labor-

Based Deferred Action and work authorization. In addition to these components, practitioners

should prepare a short cover letter, see Appendix 5, available by request only. The letter should

generally be under five pages. In the letter, practitioners should address which sub-agency

(USCIS or ICE) should adjudicate the case, with a brief discussion of relevant immigration

history or lack thereof (including entries and exits). Practitioners should also briefly demonstrate

that the worker falls within the scope of the Statement of Interest and highlight the labor

agency’s interest in the case, citing to the Statement. Practitioners should then address the

compelling government interest served by granting the request, with emphasis on the labor

agency interest as well as a short discussion of any relevant individual equities. Finally, if

practitioners are requesting the application be expedited or a fee waiver, the letter should address

the USCIS Expedite Criteria, see Part II Section D, or fee waiver criteria.

52

See Alejandro N. Mayorkas, Sec’y, U.S. Dep’t of Homeland Sec., Worksite Enforcement: The Strategy

to Protect the American Labor Market, the Conditions of the American Worksite, and the Dignity of the

Individual (Oct. 12, 2021),

https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/memo_from_secretary_mayorkas_on_worksite_enfor

cement.pdf (directing DHS component agencies, in considering case-by-case requests for deferred

actions, that “the legitimate enforcement interests of a federal government agency should be weighed

against any derogatory information to determine whether a favorable exercise of discretion is merited).

53

Before the centralized adjudication of these applications, there was some regional variation in

adjudication, with a few USCIS Field Offices issuing RFEs for significant evidence beyond the short list

of components in the new DHS guidance.

22

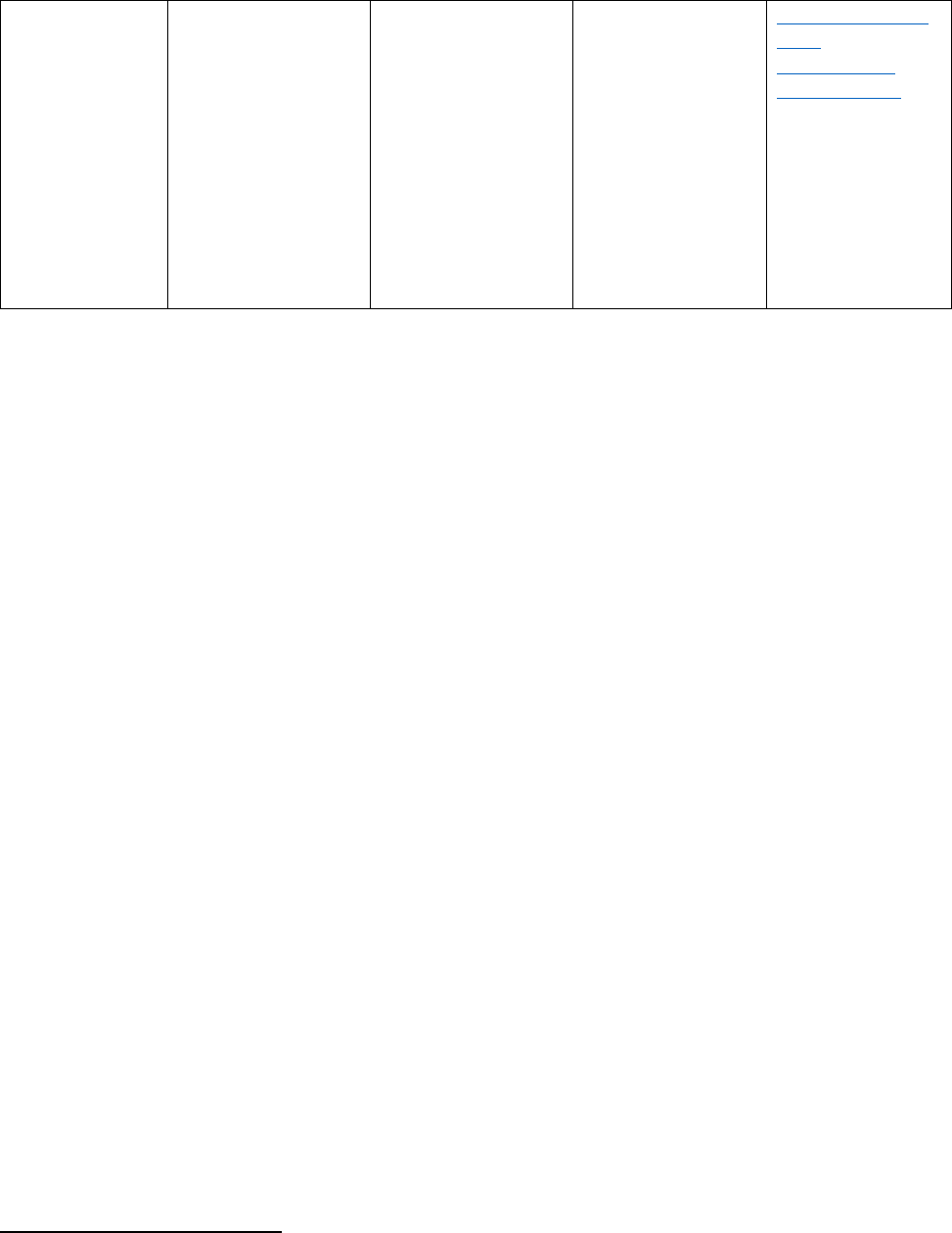

Table 4: Contents of Labor-Based Deferred Action and Employment Authorization Packet

REQUIREMENT

SUGGESTED EVIDENCE

OR ATTACHMENTS (see

sample exhibits in cover

letter in Appendix 5,

available by request only)

ADDITIONAL NOTES

Form G-28 (if represented)

None.

The applicant must physically sign

this and all immigration forms, and

electronic signatures (such as

through Adobe PDF) are not

accepted. USCIS continues to

accept photocopies or scans of

signatures.

54

Form G-325A: Biographic

Information (for Deferred

Action)

None.

Applicants should fill out all fields

with accurate information, including

disclosing any “other names used”

as well as their residences for the

past five years. Because this form

specifically requests residence

addresses, practitioners should not

substitute an office mailing address

for the client residence address.

Form I-765, Application for

Employment Authorization

None. While the form

instructions list passport-size

photos as supporting evidence,

no passport-size photos are

required for submissions to

Montclair because photos will

be taken at the biometrics

appointment.

See additional notes for G-325A.

In Part 2, Item 27, the Eligibility

Category is (c)(14) for noncitizen

granted deferred action.

Form I-765WS, Worksheet

None.

Form I-765WS is submitted as part

of DACA applications and in that

context, work authorization has

been routinely approved without

additional documentary evidence in

support of the noncitizen’s

statement in this worksheet.

$410 Fee

55

or Form I-912

For fee, money order, personal

check, cashier’s check, or Form

G-1450 to pay by credit card.

If submitting fee waiver, then

submit evidence in support of

the reason for which the

54

See Policy Manual, U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Volume 1, Part B, Chapter 2: Signatures,

https://www.uscis.gov/policy-manual/volume-1-part-b-chapter-2 (last visited Mar. 10, 2023).

55

This is the current filing fee for the I-765. Practitioners can confirm the current filing fee for form I-765

on the USCIS website. See U.S. Citizenship & Immig. Servs., Filing Fees,

https://www.uscis.gov/forms/filing-fees (last visited Mar. 10, 2023).

23

noncitizen seeks to waive the

fee (proof of receiving means-

tested benefit, proof of income

such as tax returns or W-2s, or

proof of financial hardship such

as medical bills and

outstanding debt).

56

A written request signed by the

noncitizen stating the basis for

the deferred action

Cover letter requesting deferred

action signed by applicant (see

example in Appendix 5,

available by request only).

OR

Short separate statement signed

by the applicant submitted as

an exhibit (see example in

Appendix 6, available by

request only).

Some advocates have satisfied this

requirement by asking the applicant

to sign the cover letter. Others have

preferred to have the applicant

submit a separate short statement

(relating their assent to the

practitioner’s filing of the

application to seek immigration

protection) that is attached as an

exhibit, to allow the advocate to

make last minute revisions to the

cover letter. Note that the written

request must be signed but does not

need to be sworn to under penalty

of perjury.

Statement of Interest from a

labor or employment agency

supporting the request

Statement of Interest from

labor or employment agency

requesting prosecutorial

discretion for workers in a

workplace during the time

period of the labor dispute.

This letter should serve as evidence

for establishing the labor agency’s

interest in the case. We suggest that

you do not submit voluminous

documents from the labor agency

proceeding, because USCIS is not

expert in determining if a labor

violation has occurred and should

be deferring to the labor agency’s

articulation of its enforcement

interests. It is also not necessary to

demonstrate individual harm or

hardship from the labor violation,

and so medical records or an

individual declaration are not

needed. Practitioners may include,

however, a docket sheet from the

case establishing that the case is

pending.

56

For more on this, see Am. Immig. Lawyers Assoc., Practice Pointer: Best Practices for Preparing and

Filing Form I-912, Request for Fee Waiver (Oct. 26, 2021), https://www.aila.org/advo-media/aila-

practice-pointers-and-alerts/practice-pointer-best-practices-preparing-filing.

24

Evidence to establish the

worker falls within the scope

of the Statement of Interest

Typically, this means proof of

employment during time period

of the labor dispute mentioned

in the letter, such as:

• W-2s

• Pay stubs

• Timecards

• Contracts or other

documentary evidence

• Labor agency records

that list affected

workers

• Short declaration

describing employment

terms (dates, position,

work site) (see example

at Appendix 6,

available by request

only)

Note that the standard for this

requirement is whether the worker

falls within the scope identified in

the Statement of Interest, and the

individual worker does not need to

demonstrate that they individually

suffered the labor violation nor that

they have offered any specific form