Trade obstacles

to SME participation

in trade

Section D investigates the major trade-related impediments to

SMEs’ participation in trade. A key finding in this section is that all

types of trade costs, whether they are fixed or variable, adversely

affect the ability of SMEs to participate in trade, to a greater extent

than large enterprises. Since SMEs are more sensitive to trade

barriers than large firms, removing obstacles to trade benefits SMEs

disproportionately. It is therefore important to understand what

these major obstacles are.

D

Contents

1. SME perceptions of barriers to access international markets 78

2. Trade policy and SMEs 83

3. Other major trade-related costs 91

4. ICT-enabled trade: benets and challenges for SMEs 98

5. SME access to GVC-enabled trade 102

6. Conclusions 106

Some key facts and findings

•• Tariffs•and•non-tar iff•restrictions•af fect•the•ability•to•participate•in•trade•of•

SMEs•more•adversely•than•that•of•la rge•enterprises.•

•• Trade•facilitation•promotes•the•entry•of•SMEs•into•export•markets.•Small•

expo rting•firms•profit•relatively•more•when•trade•facilitation•improvements•

relate•to•information•avail ability,•advance•rulings•and•appea l•procedures.

•• Services•SMEs•are•relatively•m ore•impacted•by•barriers•on•“establishment”•

than•by•barriers•on•“operations”,•notably•when•these•concern•mode•4•trade.

•• Logistics•tend•to•cost•more•for•SMEs•than•for•large•enterprises.•For•example,•

in•Latin•America,•domestic•logistics•costs•can•add•up•to•more•t han•42•per•

cent•of•total•sa les•for•SMEs,•a s•compared•to•15-18•p er•cent•for•large•firms.•

•• SMEs•face•more•credit•rationing,•higher•“screening”•costs•and•higher•interest•

rates•th an•larger•enterprises.•SMEs•are•also•the•most•credit•c onstrained.•It•is•

est imated•that•half•of•their•requests•for•trade•finance•are•re jected,•compared•

to•only•7•per•cent•for•multination al•corporations.

•• The•benefits•from•the•ICT•revolution•are•particularly•high•for•SMEs.•However,•

there•are•some•unique•costs•of•online•trade,•such•as•the•costs•of•access ing•

ICTs•and•the•need•for•certainty•and•pr edictability•in•regimes•governing•global•

data•transfers.•Small•f irms•in•LDCs•only•attain•22•per•cent•of•the•conn ectivity•

score•of•large•firms•in•LDCs,•compared•to•64•per•cent•in•developed•

countries.•

•• GVCs•help•SMEs•to•overcome•some•of•the•difficulties•they•face•in•accessing•

intern ational•markets.•However,•l ack•of•skills•and•technology,•together•with•

poor•access•to•finance,•logistics•and•in frastructure•costs•and•regulatory•

uncertainty•make•it•difficult•for•SMEs•to•partic ipate•in•GVCs.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

78

Section D.1 identifies the obstacles to trade that

firms perceive as major challenges for their access to

international markets.

1

Sections D.2 and D.3 provide a

sense of the magnitude of these barriers to trade and

their effects on SMEs, looking at tariff and non-tariff

barriers and other trade-related barriers, respectively.

Sections D.4 and D.5 explain how SMEs can overcome

some of these barriers through trade, particularly

online trade and global value chains (GVCs). These

subsections also explore the obstacles faced by SMEs

as they exploit the opportunities offered by online trade

and GVCs to access international markets.

1. SME perceptions of barriers to

access international markets

One way to get a sense of the main obstacles to trade

for SMEs is through survey data. The United States

International Trade Commission (USITC), the European

Commission, the World Bank, the International Trade

Centre (ITC) and the Organisation for Economic

Co-operation and Development (OECD), in conjunction

with the WTO, have conducted a number of surveys that

allow firms to be classified by their size. The results of

these surveys help to identify some of the SME-specific

obstacles that are explored in this chapter.

It is important to stress at the outset that the results of

surveys are very sensitive to the design of the survey

itself. A survey designed to identify trade costs should

typically ask the firm surveyed to indicate what costs,

out of a predefined set of options, the firm perceives

as a major obstacle to trade. If a cost is not included

in the predefined multiple choice set of costs, it will

not appear as a major trade cost. For this reason,

different surveys are not really comparable. However,

ranking the listed trade costs in each survey may still

help to understand which trade costs are the most and

the least significant for firms, and, more importantly

for the purpose of this report, which trade costs are

relatively more important for SMEs relative to large

enterprises.

Most of the information on obstacles to trade as

perceived by SMEs in developing countries does not

allow a comparison between the relative importance

of obstacles to trade between small and large firms,

because studies tend to focus on SMEs only.

2

One

notable exception is the series of business surveys on

non-tariff measures (NTMs) undertaken by the ITC,

3

which suggests that SMEs are more affected by NTMs

than large firms.

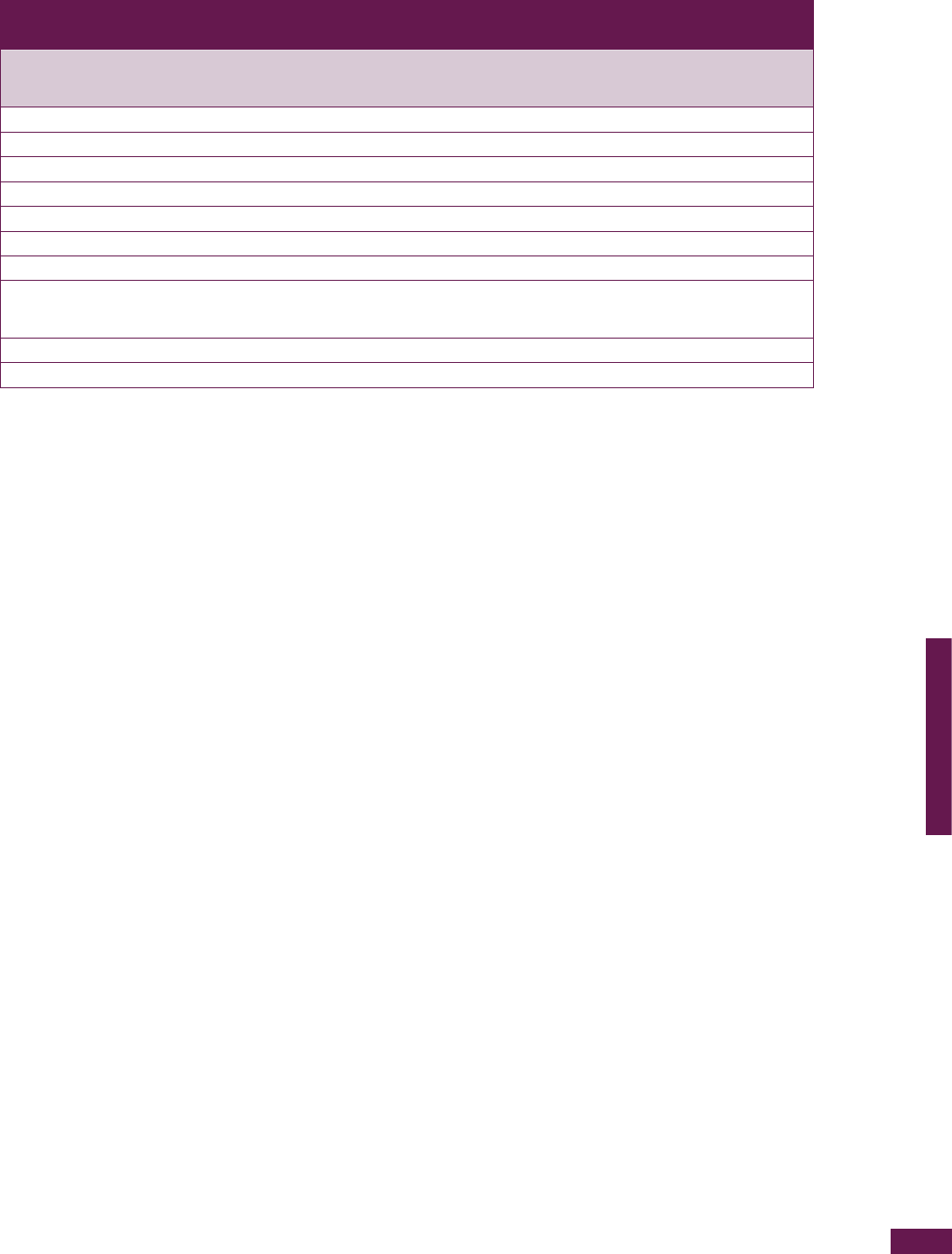

All these studies point us to some of the major perceived

obstacles to trade. Table D.1 offers a review of selected

empirical investigations conducted in developing

countries. The main obstacles to international trade

emerging from this review are:

(i) limited information about the working of the foreign

markets, and in particular difficulties in accessing

export distribution channels and in contacting

overseas customers;

(ii) costly product standards and certification

procedures, and, in particular, a lack of information

about requirements in the foreign country;

(iii) unfamiliar and burdensome customs and

bureaucratic procedures; and

(iv) poor access to finance and slow payment

mechanisms.

In order to get a sense of the relative importance of

the obstacles to trade for small and large firms in

developing countries, the database of the Fourth

Global Review of Aid for Trade (OECD and WTO,

2013) is used. This survey looks at a slightly different

question: that is, obstacles to enter and move up value

chains rather than the obstacles to trade. However,

as discussed in Section B, internationalization of

SMEs mostly takes place through indirect channels,

through the contribution that SMEs make to exports

as upstream producers in value chains. Direct exports

are almost exclusively done by large firms. In developed

and developing countries alike, the top 5 per cent of

firms account on average for 80 per cent of exports.

Therefore, the perceived obstacles to participating in

a supply chain provide important clues into the more

general question of what are the major obstacles to

trade.

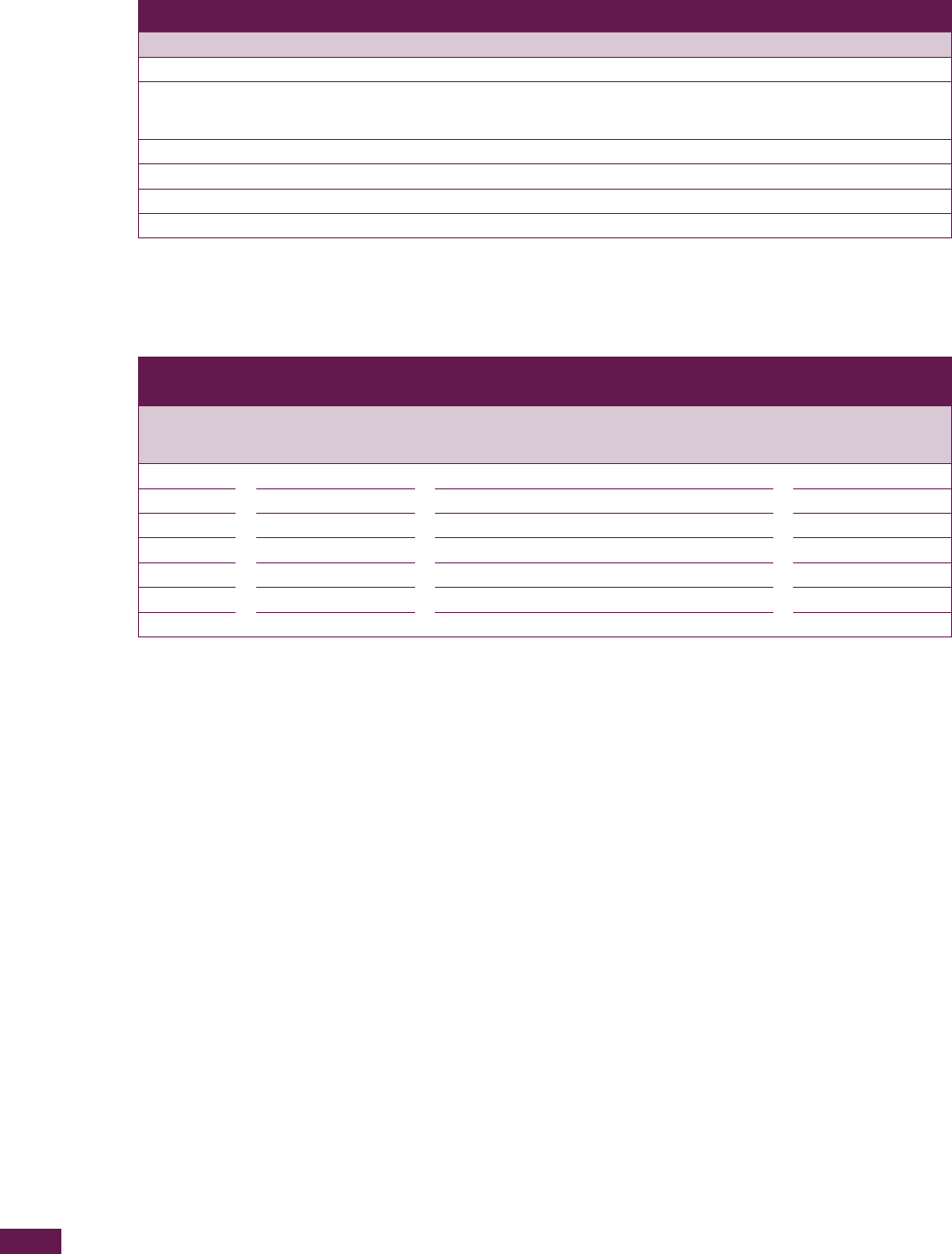

Table D.2 reports the ranking of the major obstacles

to enter and move up value chains as perceived by

interviewed firms by sectors. In the OECD and WTO

(2013) publication, a survey of 122 questions was

completed by 524 firms and business associations in

developing countries, presenting the binding constraints

these firms face in entering, establishing or moving up

value chains.

4

In addition, 173 lead firms, mostly from

OECD countries, also completed the questionnaire

to highlight the obstacles they face in integrating

developing country firms into their value chain.

5

The questionnaire focused on businesses integrated

into value chains in five key sectors: agrifood,

information and communication technology (ICT),

textiles and apparel, tourism, and transport and

logistics.

6

The original questionnaire divided responses

into five categories: micro firms with less than 10

employees; small firms, with 10 to 49 employees;

medium-sized firms, with 50 to 250 employees; large

79

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

Table D.1: A review of export barriers as emerging in selected studies on developing countries

Ethiopia Iran Jordan Mauritius Nigeria Sri Lanka

Lakew and Chiloane-

Tsoka (2015)

surveyed nine SMEs

based in Addis Ababa

producing leather

and leather products.

Kabiri and

Mokshapathy (2012)

surveyed 76 SMEs

producing fruit and

vegetables in Tehran.

Al-Hyari et

al.(2012) surveyed

135 Jordanian

manufacturing SMEs.

Dusoye et al.(2013)

surveyed 41

SMEs exporters in

Mauritius.

Okpara (2009)

surveyed 72

manufacturing SMEs

in Nigeria

Gunaratne (2009)

undertook a postal

questionnaire survey

of SMEs in Sri Lanka.

MAJOR TRADE BARRIERS

– Lack of finance

– Tariff and non-

tariff barriers

– Unfamiliar with

export procedures

– Slow collection

of payment from

abroad

– Foreign

distribution

– Complex export

document

– Political instability

in foreign markets

– Foreign exchange

rate

– Exporting

procedures/

documentation

– Communication

with foreign

customers

– Collection of

payments from

abroad

– Export restrictions

– Political instability

in foreign markets

– Tariff and

non-tariff barriers

– Unfamiliar foreign

business practices

– Sociocultural

differences

– Language

– Lack of

information on

foreign market

– Distribution

channels

– Logistic cost

– Transportation

costs

– Government

regulations and

rules

– Foreign rules and

regulations

– Collection of

payments from

abroad

– Cost of capital to

finance export

– Foreign currencies

risk

– Insufficient

information about

overseas markets

– Currency

fluctuations

– High

transportation cost

– Cost of

establishing an

office abroad

– Currency

fluctuations

– Lack of finance

– Government

bureaucracy

– Obtaining

reliable foreign

representation

– Exchange rate

policies

– Lack of export

market knowledge

– Lack of export

finance

– Difficulty in

handling export

documentation

requirement

– Transportation and

insurance costs

– Language

differences

– Lack of finance

– Corrupt

bureaucratic

practices in the

home country

– Tariff and non-

tariff barriers

– Language

– Lack of reliable

data on foreign

market

– Difficulty in

managing

advertising and

promotion

OECD and APEC countries ALADI countries CBI

7

Export Coaching Programmes

OECD (2008) surveyed 978 SMEs’ perception

of the barriers to their internationalization

across 47 countries.

A report by the OECD (2005) presents the

findings of a study on 30 SMEs in 12 ALADI

(Asociación Latinoamericana de Integración

– Latin American Integration Association)

countries on the barriers to accessing

foreign markets perceived by firms in ALADI

countries.

Vonk et al. (2015) evaluated five of CBI’s

Export Coaching Programmes (ECPs).

These programmes aim to increase exports

from developing countries into Europe. The

evaluation was conducted through interviews

and questionnaires submitted to selected

SMEs. Thirty-three responses were received

(24 were Indian firms) indicating “the most

important reason for not exporting (more) to

the EU”.

TRADE BARRIERS

– Identifying foreign business opportunities

– Limited information with which to locate/

analyse markets

– Inability to contact potential overseas

customers

– Obtaining reliable foreign representation

– Lack of managerial time to deal with

internationalization

– Inadequate quantity of personnel and/or

untrained personnel for internationalization

– Excessive transportation costs

– Lack of information and requirements

– Customs and bureaucratic procedures

– Finance and payment mechanisms

– Non-tariff barriers

– Transportation: costs, frequency, and

insecurity; inadequate logistics

– Marketing regulations and regional

agreements

– SPS and heterogeneous technical

measures

– Asymmetric physical and technological

infrastructure of countries

– Political and economic instability

– Subsidies

– Lack of business contact

– Lack of market information

Notes: These studies looked at obstacles to trade both internal and external to the firm, the table however only reports trade barriers. For example,

difficulty in obtaining information on rules and regulations in a foreign market is a barrier to export because it involves extra costs that the firms

have to meet in order to export. Lack of personnel to look into the rules and regulation in the foreign market is an internal problem of the firm.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

80

firms, with more than 250 employees; and multinational

firms, with more than 250 employees and operating

in more than one country. In Appendix Figures D.1-3,

the survey data from large and multinational firms is

combined and presented as “large firms” whereas

“MSMEs” represents the combined data from micro,

small and medium-sized firms.

A c c e s s t o f i n a n c e a n d t r a d e f i n a n c e , l a c k o f t r a n s p a r e n c y

in the regulatory environment and customs paperwork,

and delays are among the major obstacles to enter

and move up the value chains for SMEs in developing

countries. Certification costs for SMEs in agriculture

and inadequate telecommunication networks in ICT

also prevent SMEs from entering supply chains and

upgrading.

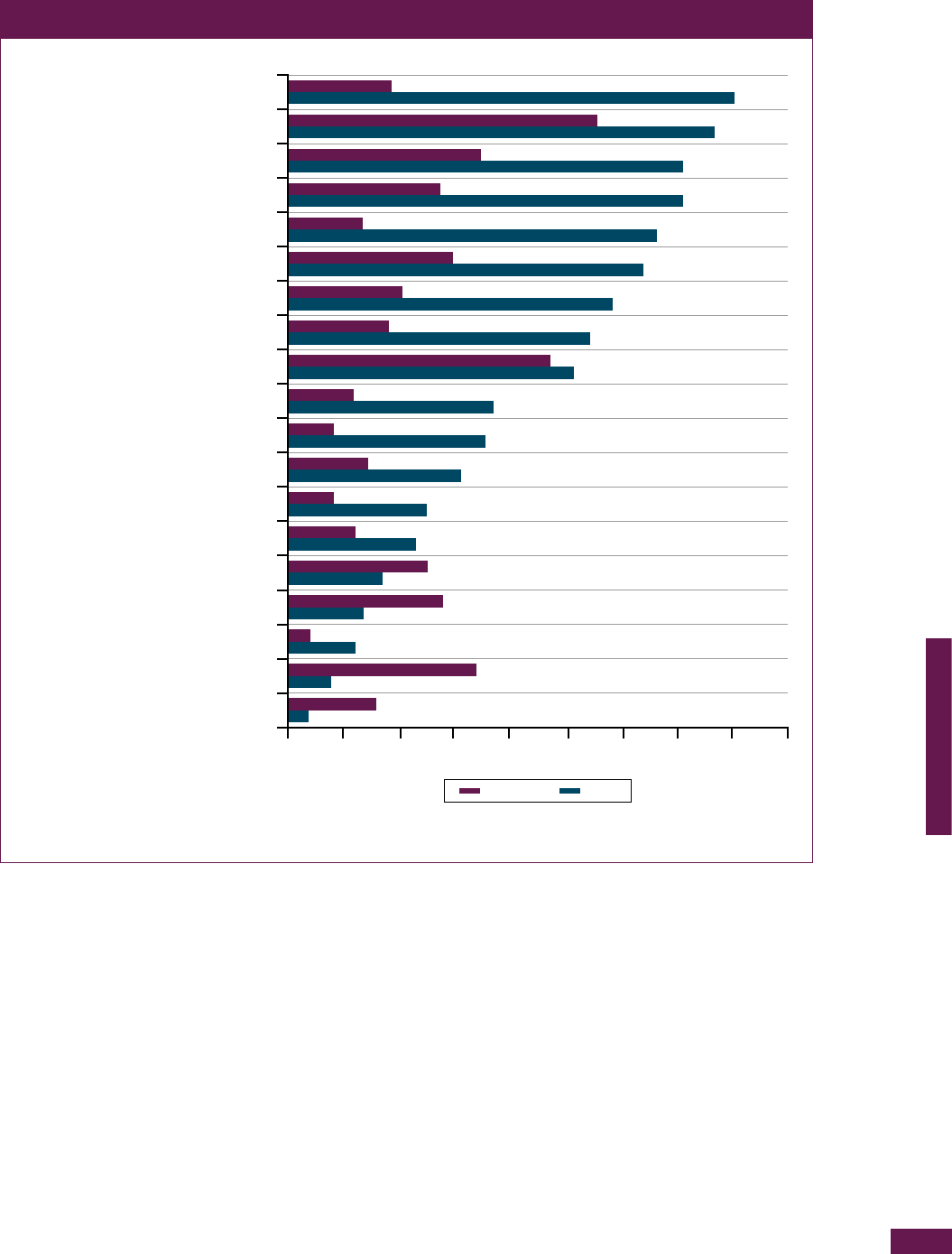

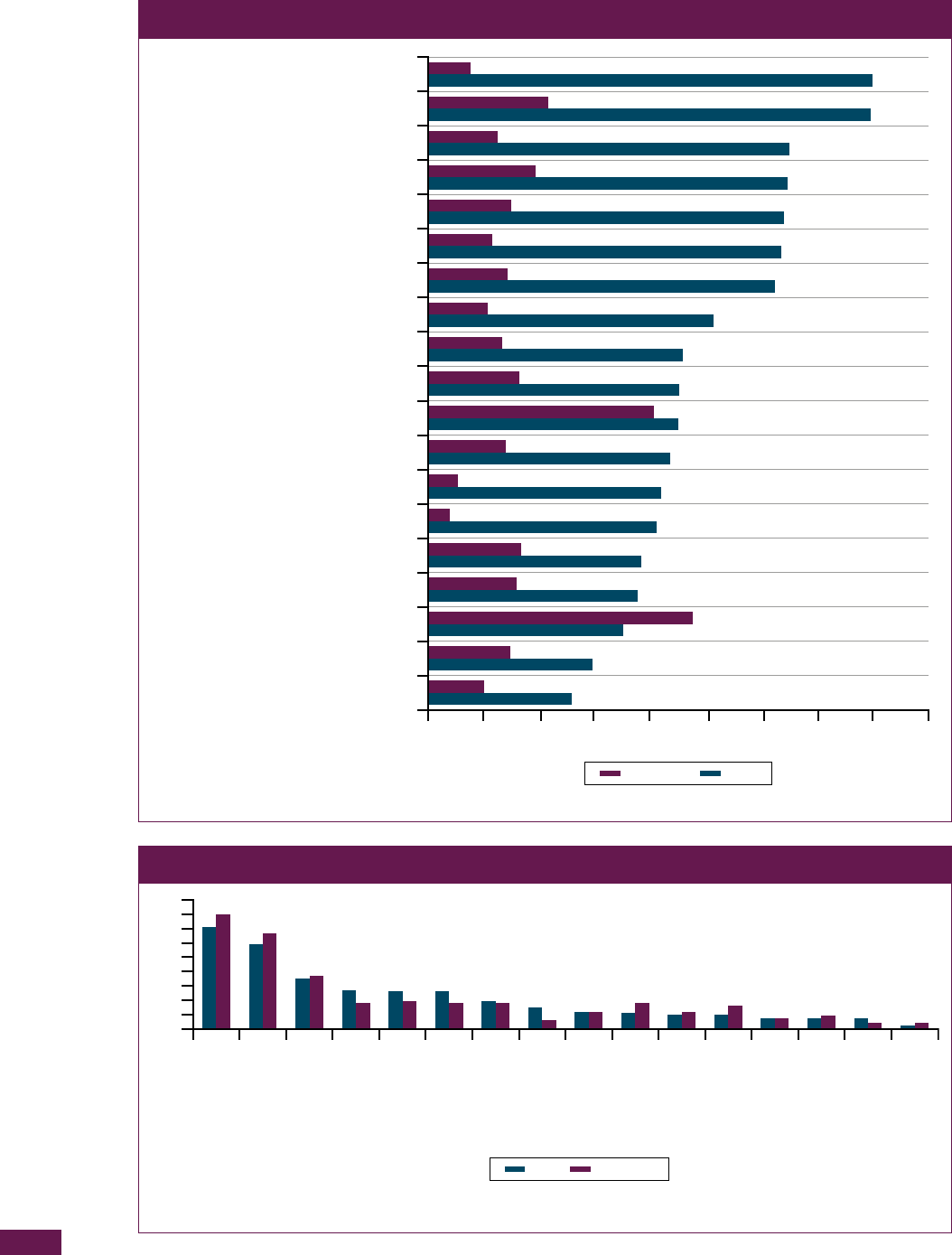

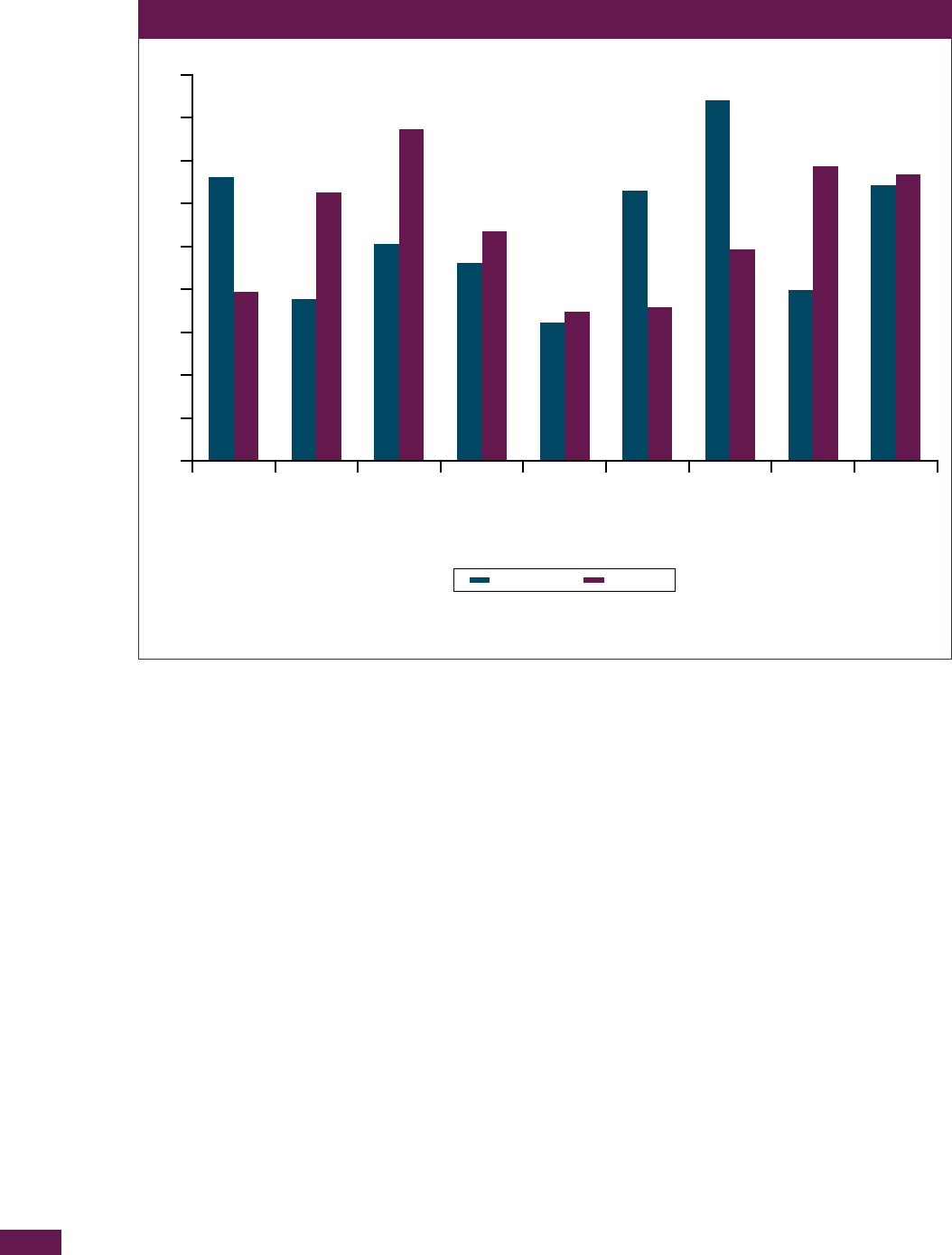

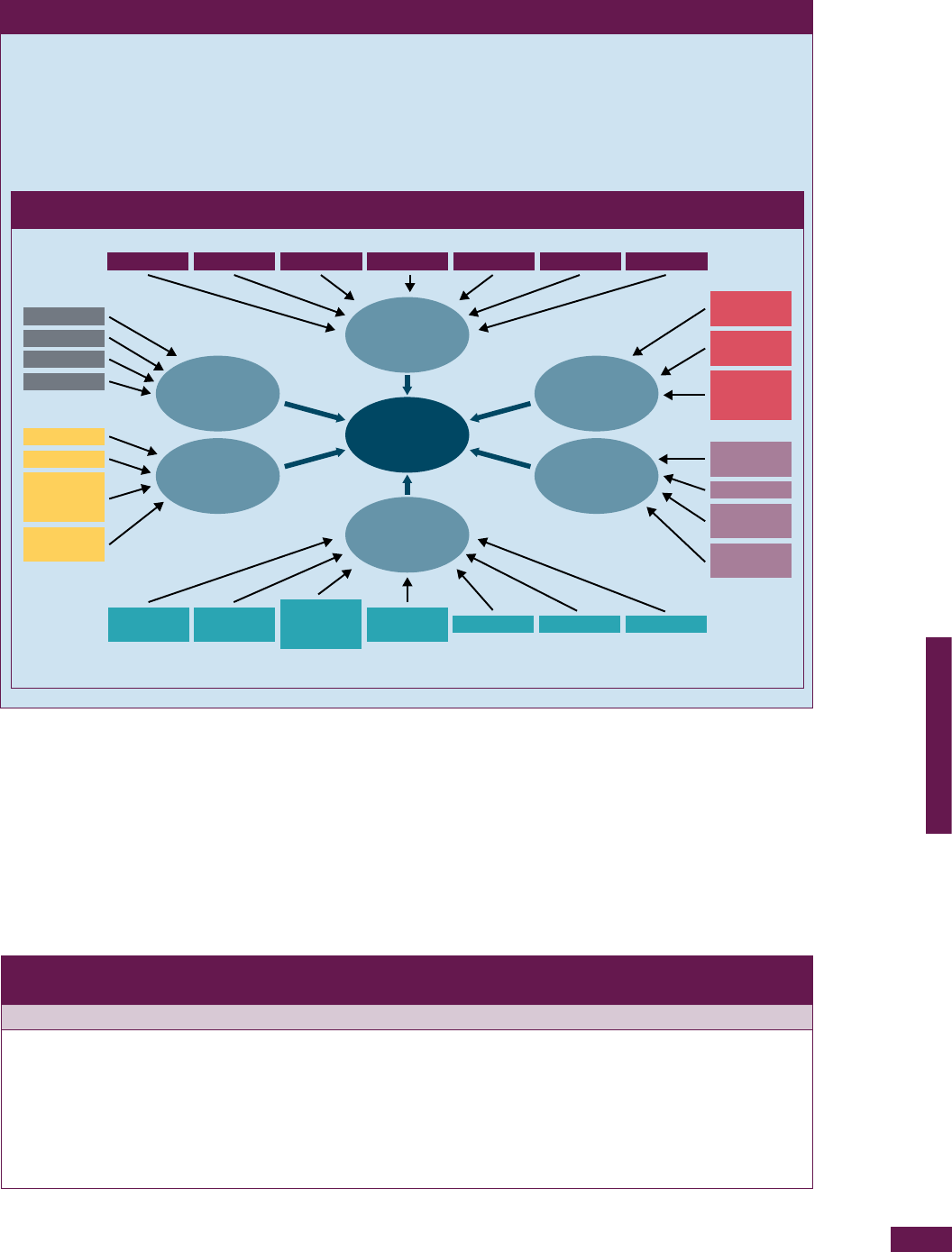

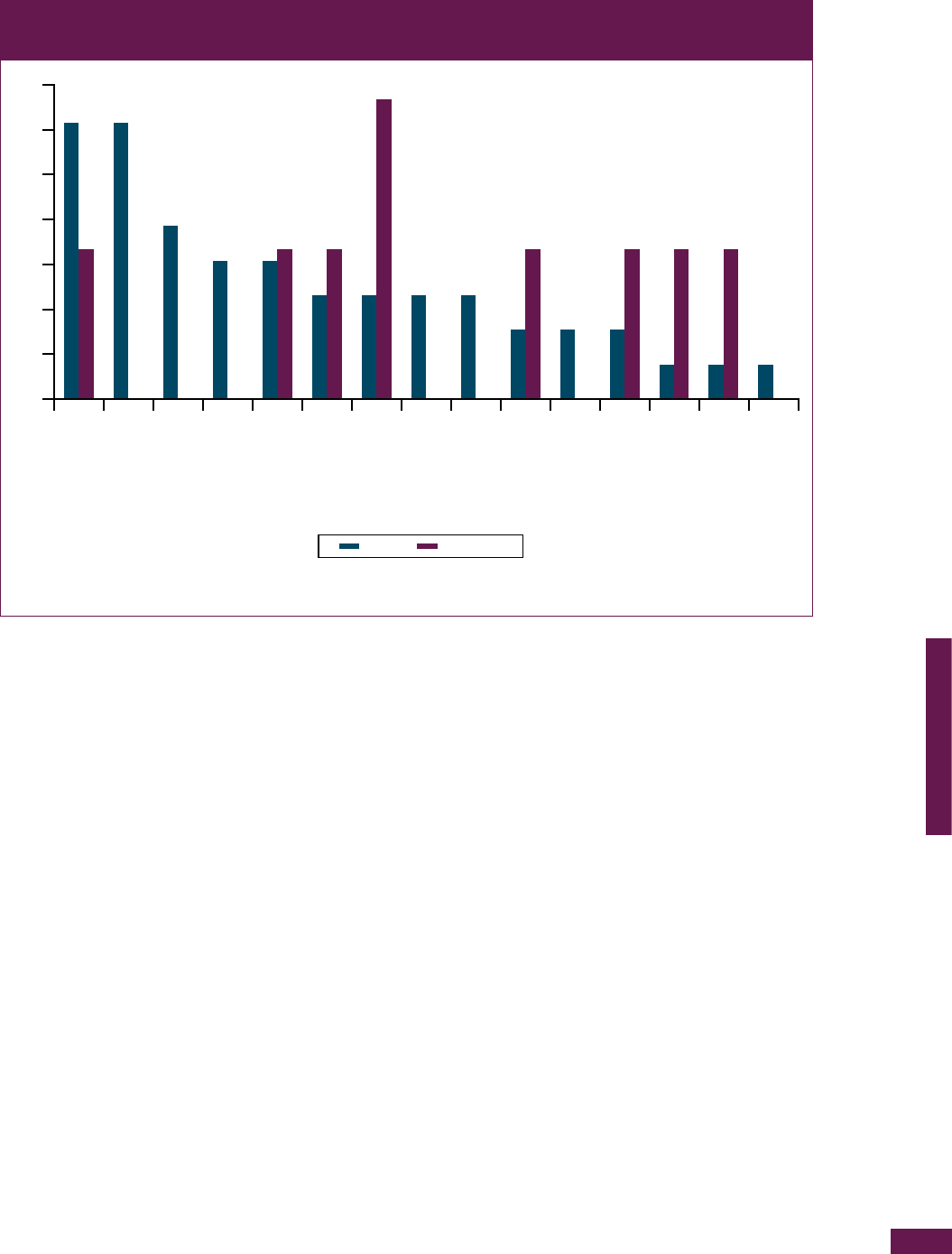

Figures D.1 and D.2 show the main perceived obstacles

to trade in manufacturing and services based on a

survey of US firms (USITC, 2010). The questionnaire

concerning the leading impediments to engaging

in global trade employs a stratified random sample

to survey more than 8,400 US firms. The results are

weighted on the basis of the proportion of firms in the

overall population and the response rates of various

categories of firms. Firms with between 0 and 499

employees in the United States are categorized as

SMEs whilst those with 500 or more employees are

categorized as large firms. Responding firms rated the

severity of 19 impediments on a 1-to-5 scale, with 1

indicating no burden and 5 indicating a severe burden.

Figures D.1 and D.2 show responses of 4 or 5 on the

1 to 5 scale, illustrating the share of SMEs and large

firms rating impediments as burdensome.

8

Interestingly, access to a foreign country’s distribution

network is perceived as the major obstacle by US

SMEs in the manufacturing sector. Conversely, this is

perceived as a relatively minor obstacle by large firms.

Similarly, high tariffs and difficulties in accessing

finance and processing payments appear to be

relatively more important obstacles for SMEs’ trade

than for large firms’ trade.

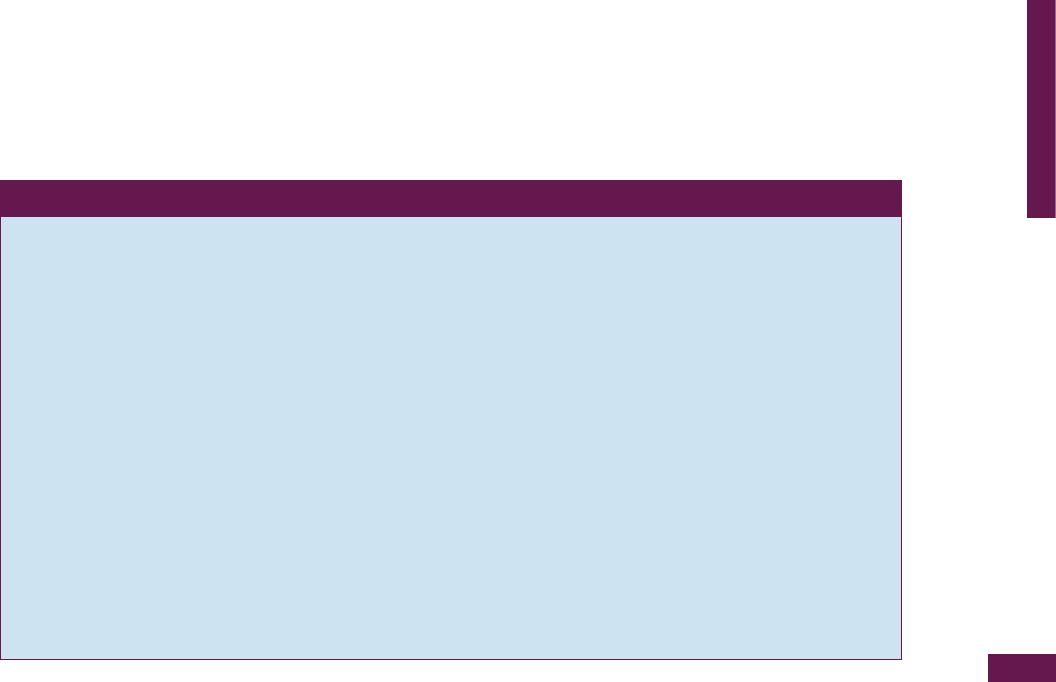

In the services sector, US SMEs reported insufficient

IP protection as the major obstacle to export. For

example, exporters of film and television programming

reported that seeking remedies to IP infringement was

often too expensive for SME producers (Independent

Film & Television Alliance, 2010).

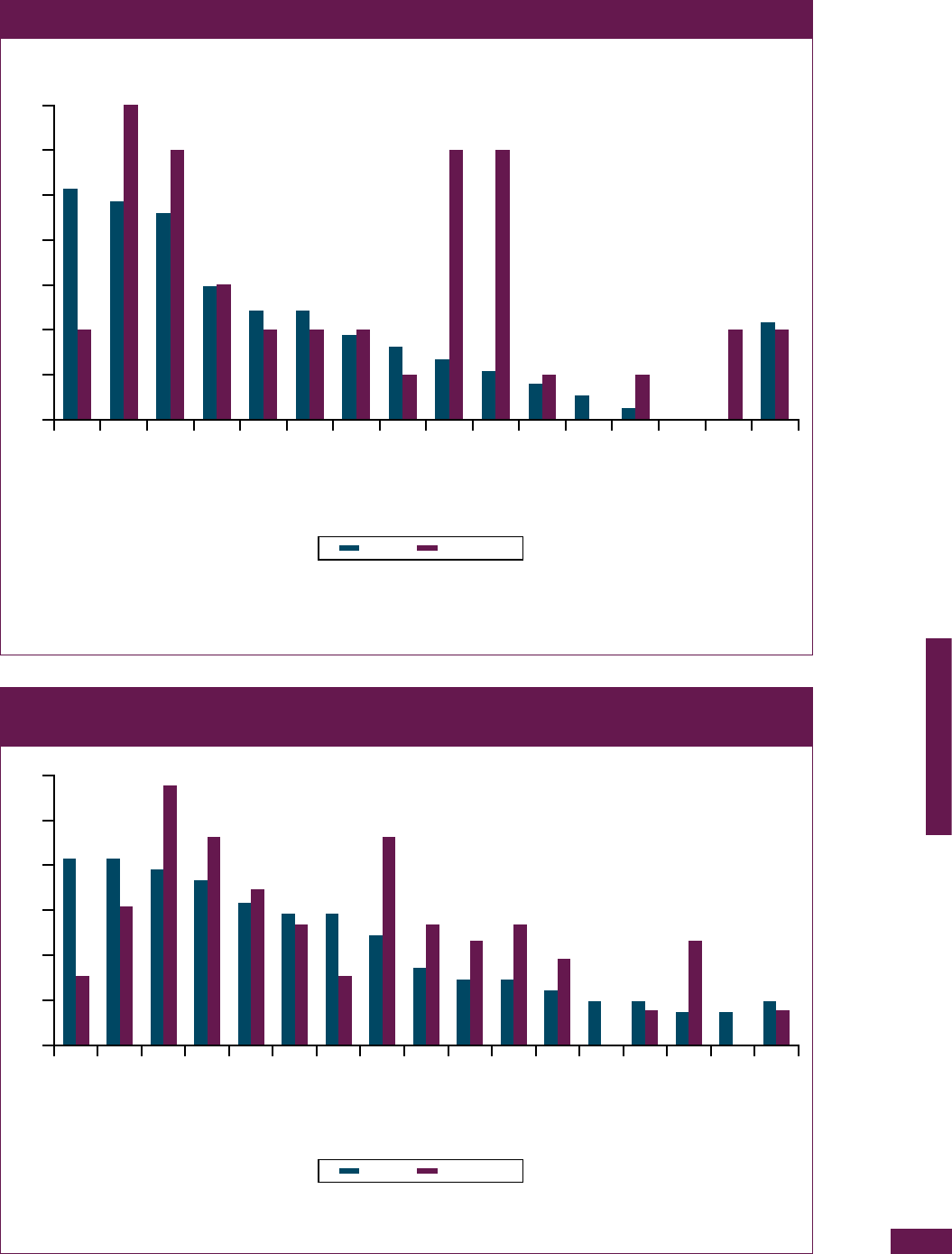

Figure D.3 from the European Commission’s

Report Small and Medium Sized Enterprises and the

Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership reports

the main obstacles to trade for EU firms exporting to

the United States (European Commission, 2014b). The

figure presents the results of an online survey of 869

European companies carried out with the support of

the Enterprise Europe Network from July 2014 until

January 2015.

The companies were asked whether they felt they

faced barriers in the US market and to identify the

nature of those barriers based on a standard list of

non-tariff measures. The respondents included micro

firms employing one to nine people, small firms with

10 to 50 employees, medium-sized firms with 51 to

250 employees, and big firms with more than 250

employees. This survey provides a broad view of the

issues that are most important for SMEs, such as

compliance with regulation and standards, customs

procedures, and restrictions on the movement of

people and of distribution channels. It also suggests

that many of these issues represent larger barriers for

SMEs than for larger firms, given that small companies

have to spread fixed costs of compliance over smaller

revenues than those of larger firms.

Regulations, i.e. sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS)

and technical barriers to trade (TBT) measures, are

perceived to be the most important obstacle to trade

for all firm sizes. More than 50 per cent of firms

Table D.2: SMEs’ top five perceived constraints in entering, establishing or moving up

value chains

Agriculture ICT Textile

Access to business finance

Transportation costs

Certification costs

Access to trade finance

Customs paperwork and delays

Access to trade finance

Lack of transparency in regulatory

environment

Unreliable and/or low band internet access

Inadequate national telecommunications

networks

Customs paperwork or delays

Access to trade finance

Customs paperwork or delays

Shipping costs and delays

Supply chain governance issues

(e.g. anti-competitive practices)

Other border agency paperwork or delays

Note: The specific question for Agriculture, ICT and Textile sectors is: “What difficulties do you face in entering, establishing or moving up the value

chains? Please select up to 5 from the following list.”

Source: OECD and WTO (2013).

81

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

identified regulation as the main obstacle to accessing

foreign markets. Border procedures are next with 30

to 40 per cent of SMEs. Price, licences and quantity

controls, as well as measures on competition are next

with 20 to 30 per cent of SMEs perceiving these to

be major barriers to access the US market. These

measures are also relatively more important obstacles

for SMEs than for large firms. Interestingly, standards

and regulations are also listed by US SMEs as major

trade barriers for accessing the EU market according to

USITC (2014). The report highlights that the different

regulatory approaches, the lack of participation of US

firms in development of EU standards, and the costs

of compliance with standards and procedures, as well

as the lack of national treatment of US certification

bodies, are all significant barriers encountered by the

US SMEs.

In sum, drawing from the existing evidence, the costs of

accessing a foreign distribution network, transportation

costs, high tariffs, access to finance and trade finance,

customs procedures, and foreign regulations, both in

goods and in services, appear to be the major obstacles

to trade for SMEs. The next subsections will explore

in more depth the reasons why these costs matter

particularly for SMEs and how e-commerce and

participation in GVCs can help to overcome some of

these costs.

Figure D.1: Leading impediments to engaging in global trade in manufacturing, US firms survey

Unable to find foreign partners

Transportation/shipping costs

Preference for local goods in foreign market

High tariffs

Difficulty in receiving or processing payments

Obtaining financing

Lack of government support programs

Customs procedures

Foreign regulations

Difficulty establishing affiliates in foreign markets

Language/cultural barriers

Lack of trained staff

US taxation issues

Difficulty locating sales prospects

Foreign sales not sufficiently profitable

Insufficient IP protection

Visa issues

Foreign taxation issues

US regulations

Large firms SMEs

0.00 0.05 0.10 0.15 0.20 0.25 0.30 0.35 0.40

0.45

Source: US International Trade Commission (2010).

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

82

Figure D.2: Leading impediments to engaging in global trade in services, US firms survey

Insufficient IP protection

Foreign taxation issues

Obtaining financing

Foreign sales not sufficiently profitable

US regulations

Difficulty establishing affiliates in foreign markets

Difficulty in receiving or processing payments

Language/cultural barriers

Visa issues

High tariffs

Foreign regulations

Transportation/shipping costs

US taxation issues

Lack of government support programs

Unable to find foreign partners

Preference for local goods/services in

foreign market

Difficulty locating sales prospects

Lack of trained staff

Customs procedures

Large firms SMEs

0.0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5

0.6

Source: US International Trade Commission (2010).

Figure D.3: Trade barriers in accessing US goods markets reported by EU firms by firm size

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

SPS measures*

TBT measures

Border procedures

Price-control measures

Licences and quantitative

controls (including quotas)

Measures on competition

Finance measures

Distribution restrictions

Intellectual property

Export-related measures

Government procurement

restrictions

Rules of origin

Restrictions on post-sales

Subsidies

Anti-dumping, countervailing

and safeguards

Investment measures

SME Large firms

*Only for exporters of food, drink, animal feed and products that come into contact with food (e.g. packaging, cooking utensils).

Source: Authors’ calculation based on European Commission (2014b).

83

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

2. Trade policy and SMEs

This subsection looks at tariff and non-tariff obstacles

to trade, their magnitude and their effects on SME

participation in trade in goods. It also discusses

barriers that may be particularly burdensome for SMEs

operating in the service sector.

(a) Tariff barriers may matter more

for SMEs

As shown in Figure D.1, SMEs in the manufacturing

sector consider high tariffs to be a greater obstacle

to exporting than large manufacturing firms do. What

explains this perception?

One explanation is the effect that higher tariffs have

on the participation of SMEs in trade. Higher tariffs

in destination markets make it more difficult for firms

to profitably export. Only the more productive firms

will export in such an environment, whilst smaller and

less productive firms will not. As tariffs are reduced,

smaller firms progressively enter in the market. Using

firm-level information for Ireland, Fitzgerald and Haller

(2014) estimate that reducing tariffs from 10 per cent

to zero increases participation of medium-sized firms

(firms with 100-249 employees) from 11.5 per cent to

14.2 per cent. But they do not find significant effects

on firms of smaller size.

A second explanation is provided by the effect that

higher tariffs have on the volume of exports of a firm.

A growing body of theoretical literature emphasizes

how the impact of trade policy depends on firm

characteristics such as size and productivity.

9

Small

firms are more sensitive to tariff changes because

they produce goods whose demand is more sensitive

to price changes or they pay lower costs to reach

additional consumers than large firms (see Box D.1 for

a more detailed explanation).

Heterogeneous effects of tariffs across firms of

different sizes can also be explained by the presence

of non-ad valorem tariffs. Specific tariffs (per unit

tariffs) and tariff rate quotas (through the imposition

of a quota licence price) act as additive trade costs,

that is a cost that is independent of the unit price of

the good. An additive trade costs has systematically a

different impact between firms that produce low-priced

and high-priced good. Clearly, adding a US$ 1 tariff on

a good for which the price is US$ 1 is a much more

restrictive measure than adding US$ 1 tariff on a good

for which the price in the market is US$ 100. If low-

priced firm are small firms, the prevalence of additive

trade costs can also explain the perceived importance

of high tariffs as barriers to trade for small firms

(Irarrazabal et al., 2015).

10

A third explanation behind small firms’ perception that

tariffs affect them disproportionately could actually be

that there is an anti-SMEs-bias in conditions of market

access. That is, SMEs face higher tariffs on average in

their export market destinations than large firms, and

this is why SMEs perceive tariffs to be a major barrier

to trade. Political economy provides some arguments

that explain this potential outcome.

In a world where governments negotiating agreements

are influenced by strong lobbying powers, large firms

Box D.1: Firms’ responses to higher tariffs

Spearot (2013) explains the differential effects across firms of a given tariff increase (reduction) with the fact

that firms face different demand elasticities. In particular, low revenue goods exhibit a higher demand elasticity.

For this reason, the traditional negative effect of higher trade costs on trade flows is amplified for low-revenue

varieties (firms with a low value of exports prior to the new restrictive measure).

11

The opposite is true when

tariffs are cut. In fact, Spearot finds that after 1994, following the Uruguay Round, for the same tariff cut, US

imports of low revenue varieties increased disproportionally more than imports of high revenue varieties. In some

cases, imports of high revenue varieties fall after liberalization.

Another study (Arkolakis, 2011) explains the differential impact of higher tariffs between small and large firms

on the basis of differences in market penetration costs. Paying higher costs allows firms to reach an increasing

number of consumers in a country. But the cost of reaching more consumers increases when a firm has already

reached a high volume of sales. That is, reaching more and more consumers becomes increasingly more difficult.

In this set-up, all firms lose from an increase in tariffs, but firms differ in their supply response depending on the

costs they face in reaching more consumers. These additional costs are large for large firms and small for small

firms. Exports of small firms grow more following tariff liberalization than do those of large firms, because small

firms face lower costs than large firms to reach additional consumers; and vice versa, large firms respond less to

tariff increases, because for each unit of export reduction they save more than small firms in terms of the costs

to reach consumers.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

84

are more likely to engage in lobbying than small firms.

Large firms have more resources and are better able

than SMEs to engage in lobbying. Moreover, sectors

with few large firms are likely to be more effective

than sectors with many small firms in influencing trade

policy outcomes. Therefore, a country’s sectoral tariff

profile is likely to depend on the size of firms in that

sector. While in a unilateral set-up, this would lead

to higher tariffs in sectors dominated by large firms

(Olson, 1965; Bombardini, 2008), when tariffs are set

in a cooperative environment, export–oriented large

firms will lobby for trade liberalization and will succeed

in lowering tariffs (Plouffe, 2012).

12

Therefore, to the

extent that large firms are present in the same sectors,

they are likely also to face lower tariffs.

Available data does not allow for a systematic

assessment of tariffs faced by individual firms in their

destination market. Ideally, in order to calculate the

average tariff faced by small firms, one would need to

know what product small firms export in each market

and average the tariff faced across markets. This type

of data is not publicly available for all countries.

To get a sense of the tariffs firms face in their export

markets, Figure D.4 shows the distribution of tariffs

faced by French manufacturing exporting firms.

Interestingly, the figure shows that (i) the bulk of both

small and large firms exporting manufacturing goods

from France face tariffs lower than 10 per cent, and that

(ii) small firms are more concentrated in sectors facing

relatively higher tariffs (the blue line is above the red line

in the figure), while large firms are more concentrated

in sectors facing relatively lower tariffs. The difference

between tariffs faced by small and large firms in France

is not all that large and, as discussed in Section C,

causality may be reversed. That is, it may actually be

the case that firms operating in sectors facing lower

tariffs grow faster. Nevertheless, these findings do

raise the question of the potential importance for some

countries to look at whether tariffs faced by firms in the

export market are particularly harsh for SMEs.

One can attempt to get a sense of a potential anti-SMEs

bias in tariff profiles for a large sample of countries

using firm-level trade flows from the OECD’s Trade by

Enterprise Characteristics (TEC) database. However,

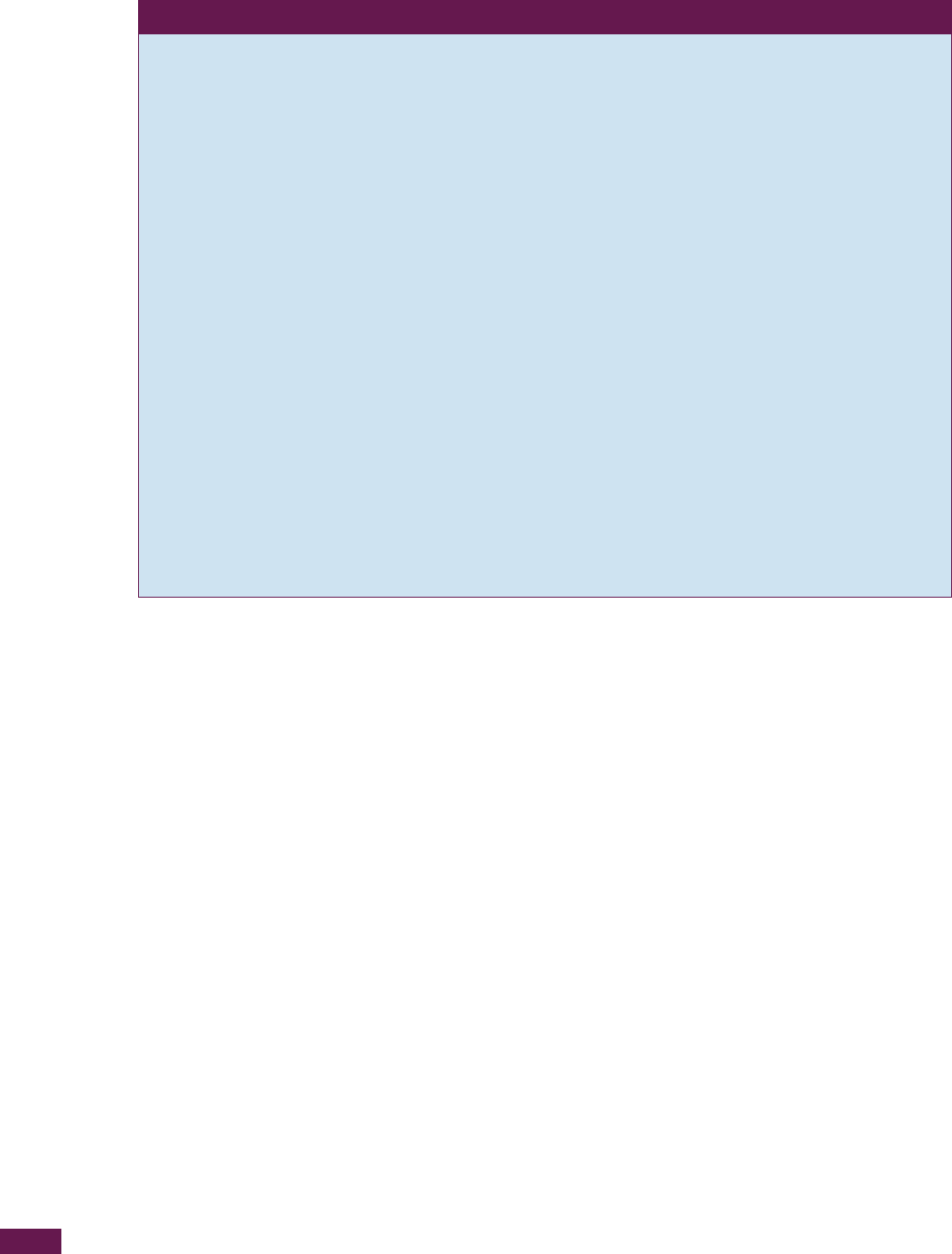

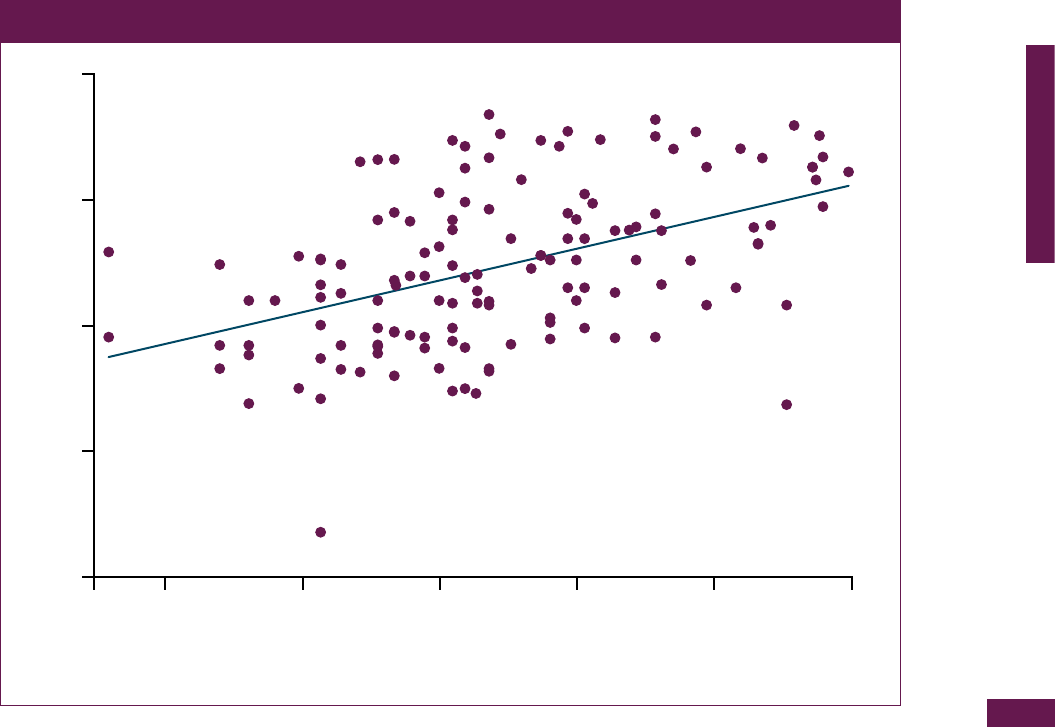

Figure D.4: French firms’ distribution by size and tariff faced in the exporting country

Density

Tariff (log scale)

20

15

10

5

0

0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5

Small firms Large firms

Note: Small firms are defined as firms falling below the 25

th

percentile in terms of their volume of exports. Large firms are those with a volume

of export above the 7

th

percentile.

Source: Extracted from background work in Fontagné et al. (2016).

85

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

note that the TEC database provides information

on total trade flows by firm size (according to five

categories: 1-9 employees, 10-49 employees, 50-249

employees, 250+ employees and unknown) and not

by individual firm. Furthermore, sectoral information is

aggregated at the 2-digit level (ISIC Rev. 4) and trade

flows are not simultaneously broken down by sector

and partner. This significantly limits the precisions of

the estimations of tariff faced by firms’ size.

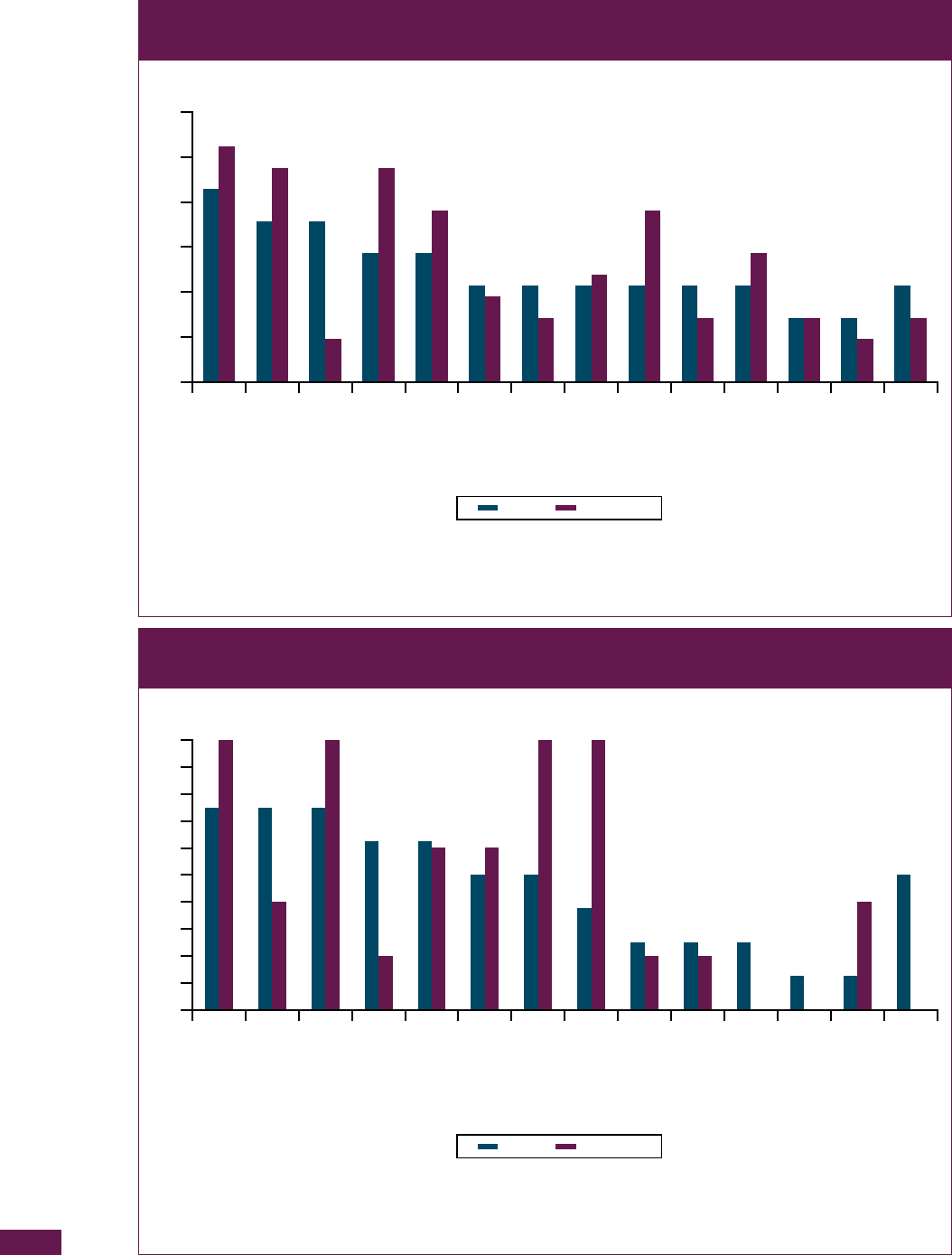

Notwithstanding these limitations, Figure D.5 shows

the weighted average effectively applied tariff that

SMEs face in their export markets for a subset of OECD

countries. In order to calculate the average tariff faced by

firms by size, data on firm-level trade flows from the TEC

database were combined with tariff data from UNCTAD’s

Trade Analysis Information System (TRAINS). Data from

2011 are used because of better data availability for this

year. The figure does not show a clear monotonic trend

between size and tariffs, but in 17 out of the 23 countries

in the sample, large firms face lower average tariffs than

at least one of the other three categories of firms of

smaller size (micro, small or medium enterprises).

(b) Non-tariff measures hinder SMEs trade

in goods

NTMs are perceived to be a major obstacle to trade by

both small to medium and large firms,

13

and appear to

be the most relevant obstacle for EU firms wanting to

access the US market (Figure D.3), as well as being

a major obstacle for US firms (Figure D.1). According

to a study by the ITC (International Trade Center (ITC),

2015c), small firms in developing countries appear to

be hit the hardest. The ITC survey, based on responses

from 11,500 exporters and importers in 23 developing

countries, shows that small firms are perceived to be

most affected by NTMs. Conformity and pre-shipment

requirements in the export market, and weak inspection

or certification procedures at home, appear to be the

major hurdles. In agriculture, certification costs are

among the hardest obstacles to move up the value

chain in developing countries, particularly for SMEs

(Table D.2). Box D.2 provides some examples – drawn

from the CBI technical assistance experience – of what

type of obstacles SMEs face in dealing with non-tariff

barriers.

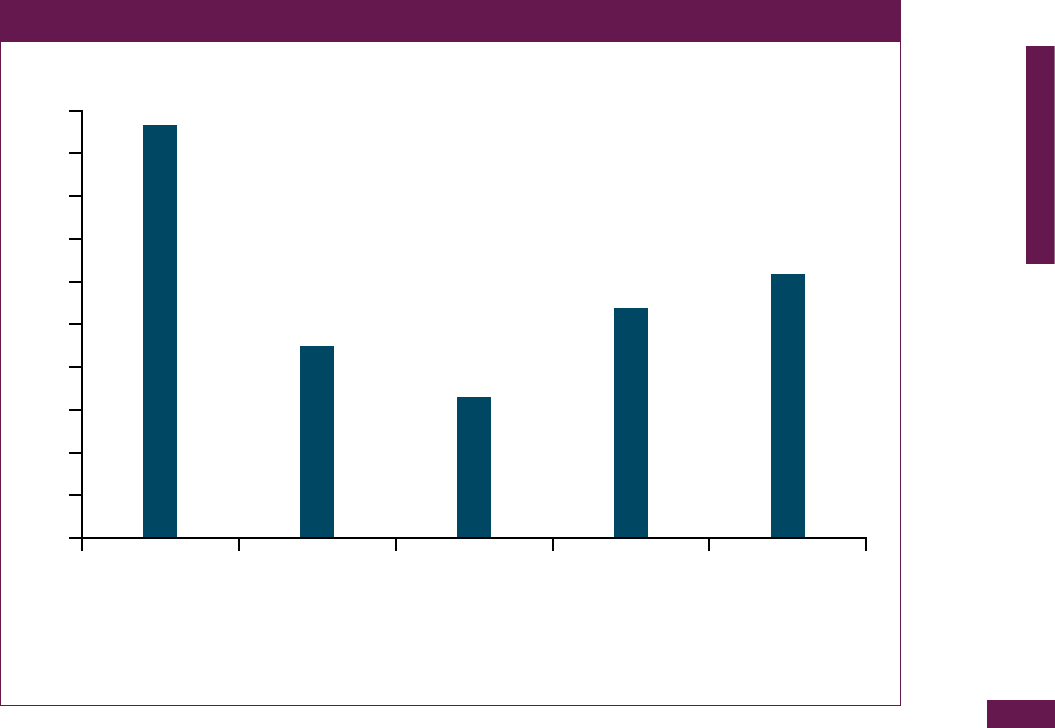

Figure D.5: Average applied tariff faced by firm size (excluding intra-EU trade), 2011

Tariff rate (%)

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

Austria

Canada

Belgium

Finland

Estonia

France

Germany

Greece

Hungary

Ireland

Italy

Mexico

Latvia

Netherlands

Poland

Slovak Republic

Slovenia

Portugal

Spain

Sweden

Turkey

United States

United Kingdom

SMEs Large firms

Note: Trade weighted averages by firm size are calculated aggregating sectoral (firm-size) tariffs across sectors using as weights firm-size

level’s export distribution across sectors. For EU countries, tariff figures refer to tariffs faced in non-EU markets.

Source: Authors’ calculations based on TEC database and UNCTAD’s Trade Analysis Information System.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

86

Very few studies provide an indication as to how NTMs

affect exporters of different sizes. Yet, the trade impact

of SPS/TBT measures is likely to depend on the size of

the exporter. NTMs are commonly regarded as having

an important fixed cost component, which significantly

differentiates them from tariffs. For example, a large

initial investment may be required for a firm to comply

with a certain foreign standard, but once the new

technology is acquired there may be no additional

variable costs.

14

Similarly, a qualification or certification

requirement for service-providing personnel may

involve an initial cost of obtaining the qualification or

certification, but no additional variable costs. Fixed

costs, independent of the volume/value of trade, are

relatively more burdensome for SMEs because they

represent a higher share of their volume of affairs.

Evidence shows that tighter TBT/SPS measures are

particularly costly for smaller firms. Focusing on the

electronics sector, Reyes (2011) examines the response

of US manufacturing firms to the harmonization of

European product standards to international norms. He

finds that harmonization increases the entry of non-

exporting firms to the EU market, and that the effect is

stronger for US firms that already export to developing

countries but not to the EU. These firms are on average

smaller than firms exporting to the EU. Focusing on

Senegal, Maertens and Swinnen (2009) show that

vegetable exports to the European Union have grown

sharply between 1991 and 2005 despite increasing

SPS requirements, resulting in important income gains

and poverty reduction. But tightening food regulation

has induced a shift from small farmers to large-scale

integrated estate production.

When a new restrictive SPS measure is introduced

in a foreign market, smaller exporting firms are those

exiting the foreign market as well as those that lose

more in terms of volumes of trade. The paper by

Fontagné et al. (2016) is the only one to provide some

evidence on how markets adjust to the introduction of

more restrictive SPS measures. Using individual export

data on French firms provided by the French Customs,

Fontagné et al. find that restrictive SPS measures (as

measured by specific trade concerns) negatively affect

both small firms’ participation in trade and their volume

of trade. In particular, they estimate that restrictive SPS

measures that have triggered the exporting country to

raise a concern at the WTO SPS Committee, reduce

on average a firm’s probability to export by 4 per cent.

The mean effect of a restrictive SPS measure on the

value of exports (the intensive margin) is approximately

18 per cent. However, this negative impact of restrictive

SPS is reduced for larger players.

Box D.2: SMEs and non-tariff barriers: the importance of transparency and predictability

Each year, the CBI (Centre for the Promotion of Imports from developing countries, part of the Netherlands

Enterprise Agency and commissioned by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands) provides trade-

related technical support to over 700 SME exporters in developing countries. An important lesson from SMEs in

CBI programmes concerns the predictability and transparency of standards and regulations.

In Kenya’s tea sector, for example, CBI has supported the product and market diversification into value-added

teas with special flavours and processed into tea bags. As CBI Expert Phoebe Owuor says: “Whereas market

access barriers in the EU markets are often high and costly to comply with for the tea-exporting SMEs, the

exports to regional and emerging markets have proved more difficult as a result of lack of information about

actual conditions”.

CBI’s experience in company-level technical assistance has shown that exporting SMEs from developing

countries increasingly invest in staff skills and knowledge pertaining to market access requirements. Increasingly,

exporting SMEs also establish clear internal processes and guidelines to ensure compliance with domestic as

well as internationally agreed regulations.

Conducting market research is key for SMEs wishing to target new markets, by looking at worldwide and local

demand, competitors, and market access conditions (including both tariff and non-tariff barriers). Useful tools

include paid services (often with a sector focus), as well as “global public goods” such as those offered by

ITC Market Access tools (including Trademap, Macmap and Standardsmap), as well as BI’s Market Intelligence

platform on the European markets, which contains content based on a combination of quantitative and qualitative

research, including inputs from 24 sectoral sounding boards consisting of experts and entrepreneurs from

European importing industries (www.cbi.eu/market-information). But SME exports continue to be hampered by

changing regulations, lack of clarity, and unpredictability.

Source: Schaap and Hekking (2016).

87

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

As shown in Fontagné et al. (2016), larger firms

lose less than smaller firms from the introduction

of restrictive SPS measures into the export market

because they are able to absorb part of the higher

costs.

15

Prices increase follow the introduction of a

restrictive measure in the export market, but this is

less the case for larger firms. This is because large and

potentially more efficient firms are likely to comply with

more stringent requirements more easily and at lower

cost. Large exporters with higher market shares and

lower demand elasticities also pass less of the cost

increase on to the consumer.

There is also some case-specific evidence that the

impact of NTMs on trade depends on the size of the

exporters. The impact of certification on the sourcing

strategy of firms in asparagus exports from Peru is an

example of the potential negative impact that NTMs can

have on small firms. Peru is the largest exporter of fresh

asparagus worldwide and the sector has significantly

increased in the last decade both in terms of volumes

of exports and number of exporters. This happened at

the same time that the number of private standards

in the sector multiplied. This success story, however,

goes together with the evidence that the proliferation

of private standards has affected the sourcing strategy

of firms, at the expense of small producers. Certified

export firms currently source less from smallholder

producers (1.5 per cent) than do non-certified firms

(25 per cent). Before becoming certified (in 2001),

instead, export firms sourced more from smallholder

producers (20 per cent) (Maertens and Swinnen, 2015).

(c) Customs procedures

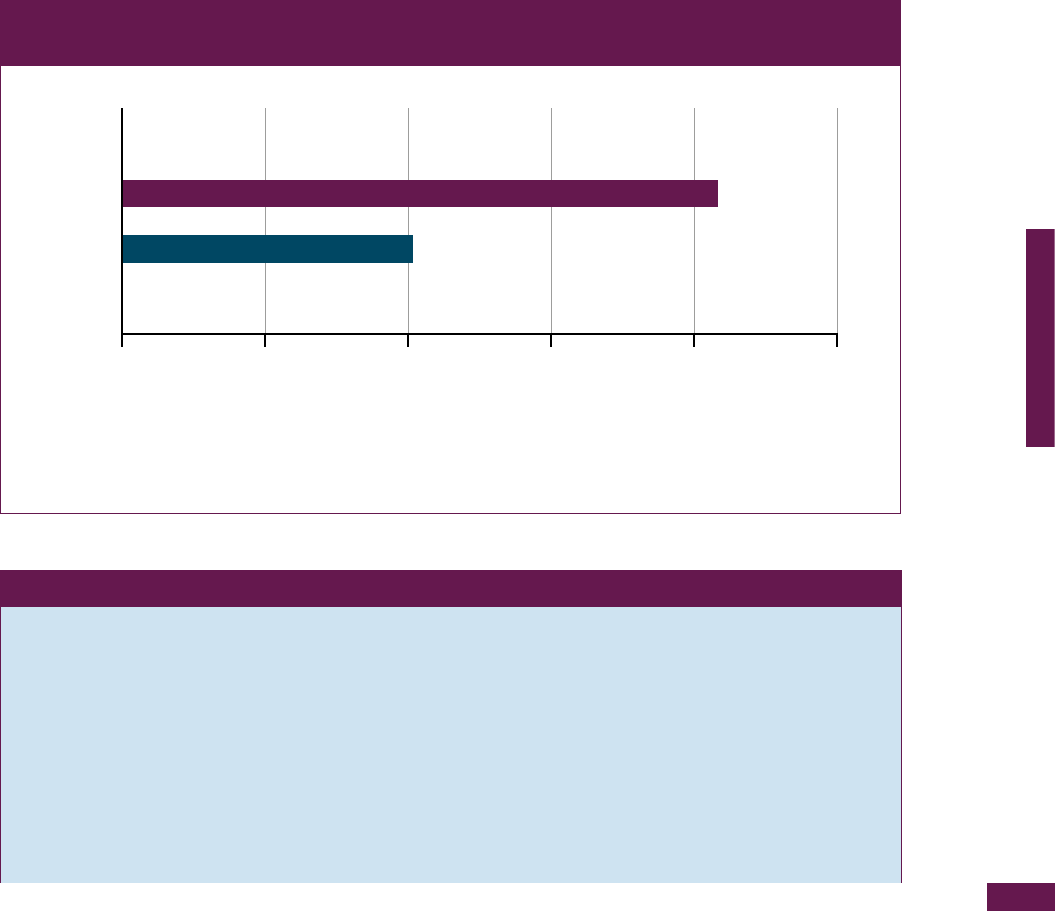

Gains from trade facilitation are likely to be larger

for SMEs. As trade costs fall, more and more firms,

increasingly less productive, will start to export (see

Section C). Trade facilitation can, therefore, promote

the entry of SMEs into export markets. The simple

correlation between the minimum size of exporting

firms by country and export time support this

possibility. As shown in Figure D.6, the lower time to

export is associated with smaller exporting firms. But

empirical evidence on the heterogeneous effect of

trade facilitation on trade by firm size is limited.

Existing econometric evidence on the impact of trade

facilitation on exports at the firm level supports the

view that both large firms and small firms benefit from

Figure D.6: Relationship between minimum export sale (per country) and time to export

2

0

5

10

15

20

2.5 3

ln(time to export) in days

ln(minimum export sale) in US$

3.5 4 4.5

Source: WTO (2015).

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

88

trade facilitation, and that, in particular, small firms

benefit the most in term of exports, when the effect

of trade facilitation on fostering the entry of new firms

in the export market is also taken into account. Using

the World Bank Enterprise Surveys database, Han

and Piermartini (2016) show that the effect of trade

facilitation on trade depends on a firm’s size. When both

exporting and non-exporting firms are included in the

sample of analysis, micro, SMEs profit more than large

firms from reduced time to export. Han and Piermartini

estimate that trade facilitation measures that reduced

export time for all firms at the median regional level may

boost the share of SME exports by nearly 20 per cent

and that of large firms by 15 per cent. This is because

small firms are more likely to start exporting. When only

exporting firms are taken into account, (Hoekman and

Shepherd, 2015) find, however, that reduced time to

export does boost firms’ export shares, but it does this

equally for small and large firms.

There is also evidence that different provisions of the

Trade Facilitation Agreement affect small and large

firms differently. Using the firm-level customs data of

French exports, and looking at the effects on a firm’s

export of improving trade facilitation in the importing

country rather than in the exporting country itself,

Fontagné et al. (2016) show that while, in general, all

exporting firms gain from improved trade facilitation

in the importing country, the relative effects on small

and large firms vary according to the type of facilitation

measure.

The study finds that small exporting firms profit

relatively more when trade facilitation improvements

relate to information availability, advance rulings and

appeal procedures. For example, if all East Asian and

Pacific countries adopted the region’s best practices

in measures that improve information availability, small

exporting firms would export 48 per cent more than

they currently do and medium-sized firms would export

25 per cent more (there would be no significant effect

for big firms). Large exporting firms profit relatively

more when the importing country’s facilitation reforms

relate to the simplification of formalities. One possible

explanation, provided by the authors, is that the

simplification of formalities reduces corruption at the

border and that this, in turn, has a positive effect on the

propensity of large firms to trade. Large firms are, in

fact, empirically found to be more sensitive than small

firms to corruption.

(d) Trade policy and services SMEs

Assessing which trade barriers are particularly

burdensome for SMEs’ services exports presents

a number of challenges. First, services trade as

defined in the GATS is multimodal: it encompasses

not only cross-border transactions (mode 1), but also

consumption of a service in a foreign territory (mode

2) and the movement of the supplier abroad, either

to establish a commercial presence (mode 3) or in

person (mode 4).

16

Most services may be traded via

more than one mode of supply. As such, the impact

of barriers to trade in one particular mode is likely to

depend on whether or not the mode in question is a

service supplier’s preferred export avenue. Second,

there are no theoretical analyses and few empirical

studies directly addressing this question. Third, little is

known about the characteristics of services exporting

SMEs, and what information exists is largely based on

experiences in developed countries.

Nevertheless, available empirical literature on the

export behaviour of services SMEs (Lejárraga and

Oberhofer, 2013) provides a useful background against

which to assess this question. Service SMEs that export

employ relatively more highly skilled workers, pay higher

wages and are more innovative, but are not necessarily

always larger. The positive relationship between firm

size and export likelihood is in fact inconclusive in the

case of services, whereas it is firmly established for

manufacturing.

Using firm-level data for France, Lejárraga and Oberhofer

(2013) find that firm size has a positive effect on the export

probability for suppliers of financial, ICT and professional

services, but no impact for travel service providers, for

instance. Importantly, as already discussed in Section

B.1 and evidenced by the survey results presented in

Section D.1, the one element that emerges strongly

from available research is the substantial heterogeneity

in traders’ characteristics across services industries

(Lejárraga et al., 2015). Drawing firm conclusions about

“service-exporting SMEs” as one monolithic category is,

therefore, rather difficult.

In terms of how to export, services SMEs’ choice of

mode of supply depends on the comparative cost and

expected revenue involved. They may choose one

mode, or may wish, or need, to rely on several modes

to serve foreign markets. Mode 1 trade in ICT services,

for instance, will be facilitated by associated mode 4

movements that enable the supplier to be physically

close to its customers. Moreover, not all modes are

equally feasible ways of exporting services: hotel

services can be supplied essentially via mode 2 only,

for instance, while exports of construction services are

hardly possible cross-border.

Persin (2011) argues that service SMEs tend to lean

towards “soft” forms of internationalization, because of

size constraints, and export essentially via mode 1 and

mode 4. Kelle et al. (2013) analyse firms’ choices of

exporting across borders or through the establishment

89

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

of a commercial presence. Relying on firm-level data for

Germany, they empirically confirm SMEs’ preferences

for mode 1. In a study by Henten and Vad (2001), Danish

SMEs are also found to export services by relying more

on cross-border trade than on the establishment of a

commercial presence, except in the case of financial

services.

In addition to direct exports, SMEs have recourse also

to indirect forms of internationalization. These include

indirect exports through intermediaries, which were

discussed as part of the GVC analysis in Section B.2,

technological cooperation with foreign enterprises or

non-equity contractual modes such as franchising and

licensing. Nordås (2015) observes that manufacturers

often rely on franchises with services SMEs, such as

car dealerships, petrol stations, pubs or hairdressers, to

distribute their goods.

Barriers to services trade are virtually all of a regulatory

nature, but some are likely to affect SMEs more than

others. A useful distinction in this sense is between

measures that affect firms’ ability to enter or become

established in a foreign market (“establishment”

measures), and those that have an impact on their

operations once they are present in that market

(“operation” measures) (see WTO, 2012 for a fuller

discussion). As the former usually designate fixed

costs, whereas the latter are more likely to imply

variable costs, it may be assumed that, for SMEs,

“establishment” measures will be relatively more

burdensome (Deardorff and Stern, 2008).

Given how heterogeneous traders are across services

industries, differences in the openness of regimes in

different sectors need to be considered. Figure D.7,

which is based on the World Bank’s Services Trade

Restrictiveness Index (WB STRI), provides information

about the restrictiveness of services policies across five

sectors. It shows that the steepest barriers are found

in professional services and transportation and, to a

slightly lesser extent, in telecommunication services.

In light of the discussion above, it is useful to

differentiate further, across different sectors, between

measures that restrict firms’ ability to establish in a

foreign market and those that affect their operations

once abroad. Using the data underlying the OECD

Services Trade Restrictiveness Index (OECD STRI),

Figure D.8 presents the relative importance of such

Figure D.7: Restrictiveness of services trade policy by sector, 2009

Restrictiveness of services trade policy

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

Professional

Retailing

Financial

Telecom

Transport

Source: Authors’ calculations based on World Bank STRI data for 2009.

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

90

measures for the sectors and economies covered by

the index in 2015. It should be noted that, although

the titles of the World Bank and OECD indices are the

same, the two are different in scope, methodology and

country coverage. The OCED STRI is more recent and

covers a greater number of sectors, while the World

Bank STRI is much wider in terms of country coverage

but does not offer a ready-made distinction between

“operation” and “establishment” measures.

17

As Figure D.8 illustrates, “establishment” barriers are

most important for professional services, followed

by audiovisual, transport and financial services. This

would suggest that, in these sectors, SMEs will find it

relatively more challenging to export.

Trade barriers impact the mode(s) of supply which firms

rely on to serve foreign markets. As discussed, SMEs

depend more on cer tain mode s than on others. Although

no empirical analysis exists that can disentangle the

specific impact of trade policies on SMEs’ choice of

export mode, obstacles in those modes clearly affect

SMEs’ participation in services trade more severely,

relative to large companies in the same situation.

Still, one may assume that, as least as far as small

and micro enterprises are concerned, mode 3 would

not be viable even in the absence of any meaningful

restrictions, in light of the significant costs involved in

establishing a commercial presence abroad. Barriers

to mode 3 may therefore affect the smallest firms

relatively less than barriers to other modes of supply.

Indeed, most of the discussion of the measures that

affect the export ability of services SMEs focuses on

trade via modes 1 and 4, and, to a much more limited

extent, mode 3 (see, for instance, Adlung and Soprana,

2012; Nordås, 2015).

18

When it comes to mode 3, SMEs are impacted in

particular by measures that prescribe commercial

presence in the form of a subsidiary. As it is cheaper and

administratively less burdensome if firms are allowed

to become established through representative offices

or branches, SMEs are likely to be significantly more

impacted by requirements to be locally incorporated.

Other measures that can be assumed to have similar

effects include minimum capital requirements, training

obligations, residency requirements and the granting of

subsidies to domestic SME suppliers only.

Figure D.8: Average OECD STRI by type of measure, by sector, 2015

0

0.02

0.04

0.06

0.08

0.10

0.12

0.14

0.16

0.18

Audiovisual

Courier services

Construction

Distribution services

Computer services

Financial services

Professional services

Telecommunications

Transport

Establishment Operation

Note: The value of the OECD STRI ranges from 0 to 1, where 0 is completely open and 1 is completely closed.

Source: Author’s calculations based on the OECD STRI data for 2015.

91

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

The most relevant barriers, as far as mode 1 is

concerned, are measures requiring firms to establish

a commercial presence in the host market in order

to supply cross-border services. Similarly, measures

imposing data localization requirements in foreign

markets are bound to impose a higher burden on SMEs.

Finally, barriers to mode 4 trade would appear to be

of particular relevance for SMEs. For starters, the

mode 4 category of “independent professionals” (i.e.

self-employed individuals supplying a service abroad)

concerns SMEs by definition. As such, all barriers to

the movement of independent professionals impose a

burden wholly, and solely, on SMEs. This is especially

crucial when considering the relevance that mode 4

is likely to have for exports from these “ultra-micro”

enterprises, and in view of the higher probability that,

given their relatively more highly skilled workforce,

smaller services firms may be contracted to supply

services internationally.

Barriers applicable to the mode 4 category of

“contractual service suppliers” can also be particularly

burdensome for SMEs. Contractual service suppliers

are employees of a service firm who enter the export

market pursuant to a contract concluded between their

employer and a local consumer. Similarly to independent

professionals, services exported by contractual service

suppliers are not contingent on the establishment of

a commercial presence, and are, therefore, less costly

to provide. Therefore, market access limitations such

as quotas or economic needs tests, as well as any

relevant discriminatory measures such as residency

requirements, non-eligibility under subsidy schemes,

discriminatory tax treatment or obligations to train

domestic workers that are applicable to these two

mode 4 categories, disproportionately affect SMEs.

There are a number of other services measures that,

although not trade barriers per se (i.e. not falling under

the six measures that are defined as market access

limitations under the GATS and not violating the GATS

national treatment disciplines), may nevertheless restrict

trade opportunities for SMEs in particular. Amongst

these are licensing and qualification requirements and

procedures, and technical standards, to the extent

that these are particularly costly or administratively

complex to fulfil and, as such, significantly increase

the fixed cost of entering a foreign market. It should be

noted, however, that, provided that these measures are

non-discriminatory, their effect is not only felt only by

foreign SMEs, but also by domestic ones. By raising the

cost of serving the domestic market, such measures

disproportionately affect small firms of any origin.

Still, it is true that, for those firms that export, domestic

regulatory measures are a cost to be borne in each

individual foreign market. SMEs are therefore less

likely than larger firms to export to multiple markets,

thus potentially reducing the extensive margin of trade.

This seems to be corroborated by empirical research.

Lejárraga and Oberhofer (2013) and Lejárraga et

al. (2014) find that SMEs’ export decisions are very

persistent, i.e. firms which enter a foreign market are

likely to continue to export services to that market over

the years. Their research also shows that, once they sell

abroad, services SMEs tend to export a higher share

of their total output compared to larger firms. As such,

they are disproportionally affected by trade-restricting

measures.

Lack of recognition of foreign work experience,

education or qualifications is also likely to prove a

relatively more burdensome hurdle for SMEs wishing to

export regulated services. In the absence of recognition

arrangements that “fast-track” the authorization to

supply a service in a foreign market, suppliers of

regulated services are required to embark in costly

and lengthy processes to demonstrate that they are

qualified to supply the service in question. Again,

suppliers will need to so for every market they wish to

enter. To the extent that firms have the resources to

set up a commercial presence abroad, they may obviate

this obstacle by hiring locally qualified professionals,

but this is likely to prove prohibitively expensive for

SMEs.

Visa and work permit requirements and procedures can

also be assumed to impose a relatively higher burden

on SMEs, in light of the greater relevance mode 4 has

for their exports. This is likely to be especially true for

developing country SMEs, as their employees (who are

usually nationals) tend to be subjected to comparatively

more stringent visa requirements, particularly so

when they are seeking to access other developing

country markets.

19

The introduction of programmes to

streamline entry formalities for businesses accredited

as “premium visa traders”, i.e. usually large concerns, is

also likely to put SMEs at further relative disadvantage

compared to bigger firms.

3. Other major trade-related costs

This section focuses on those firm-perceived obstacles

to trade identified in Section D.1 that go beyond the

strict definition of trade policies (tariff, non-tariff and

regulatory barriers discussed in Section D.2). Many

of the trade costs discussed in this section are those

arising from the services needed to do trade, such

as distribution costs, transportation costs and cost to

finance trading activity. In this respect, the analysis

here differs from the discussion in Section D.2(d),

which discussed obstacles to trade in services and not

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

92

the costs related to the use of services necessary to

the trading activity.

(a) Information and distribution channels

Beyond market access and regulator y barriers for goods

and services, additional trade costs that are higher

for SMEs can be identified in relation to information

and distribution channels. There are intermediary

companies, besides producers and consumers of goods

and services, which participate in creating the structure

of a distribution network, with a specific function to

fulfil. Distribution channels can, therefore, take various

forms: (i) direct sales of producers to clients; (ii) sales

through a retailer; (iii) sales through wholesaler(s)

and retailer, or (iv) sales using an agent working on

a commission basis (who can eventually bridge gaps

between producers and wholesalers/retailers or

clients). There are also some important functions that

support an efficient distribution network which may or

may not be fulfilled by these intermediaries, e.g. market

analysis, advertising, transport/logistics or after-sales

services.

For SMEs, having access to distribution networks may

be a crucial component to develop their business, in

particular for diversifying their customers within a

region or worldwide. As shown in Section D.1, reaching

clients in other economies may be challenging

for SMEs without access to relevant distribution

channels and related functions. This is reflected in

the high proportion of responses citing trade-related

impediments for SMEs in Figure D.1 (“Unable to find

foreign partners” and “Transportation/shipping costs”)

for the goods trade. For services, this can to a certain

extent be illustrated by the number of responses citing

“Difficulty establishing affiliates in foreign markets” in

Figure D.2, which reflects the need in many cases for

proximity with the client given the intangibility of the

products being traded and, in some instances, adapt

to the culture/language of the destination market.

Access to information by potential SME exporters on

distribution channels and destination markets can,

therefore, also be related to all that is described above.

Items in the distribution channel that can be identified

as hurdles for SME exporters are: having and choosing

goods or services fit for the export market, whether

targeting specific countries, regions or worldwide;

making their products known to potential clients;

delivery of products and associated risks (e.g. transport

and physical delivery of goods and services; online

delivery of products, ensuring that eventual property

rights are not at threat). In that context, it is important to

note that some intermediaries, such as those engaged

in e-commerce, may themselves be SMEs. In addition,

SME exporters also need to face the cost of gathering

market information, as well as access to regulatory

information in export destinations.

A firm that wants to export goods or services needs to

know about the regulations in the economy to which

it intends to export (for example, technical regulations

about the characteristics that a product needs to

meet, rules and regulations relating to trade). That

firm also needs information about export opportunities

in the destination market. Lack of knowledge about

regulations could result in the product not complying

with the importing country regulations, which, in turn,

could cause the firm to face the costs of the product’s

rejection at the border of the target country. Lack of

knowledge about the demand in the export market

may also induce profit losses. Gathering information

is costly. Anderson and van Wincoop (2004) estimate

that approximately 6 per cent of total trade barriers are

information costs. These are broadly defined to include

information flows generated by migration networks

Rauch and Trindade (2002), volume of telephone traffic

and number of branches of the importing country’s

banks located in the exporting country.

Gathering information is a crucial factor in determining

export decisions, but it bears a cost. This cost is to

a large extent independent of how much a firm will

export. Therefore, it is a cost that affects especially

small firms that are less capable than large firms of

spreading information costs across output. A recent

survey by the Conférence permanente des chambres

consulaires africaines et francophones (CPCCAF),

asking “When exporting, what are the main types of

information you need?”, shows that trade contacts

and business opportunities are the most significant

information barrier faced by small firms in Africa,

followed by information on relevant regulations, and on

export support measures (see Table D.3).

Delivery and logistical aspects are also an issue in

trade, in particular for SMEs, whether as producers

or intermediaries. SMEs often have to rely on

existing solutions to have their products delivered

to clients. These include services offered by postal

systems, express delivery services, cloud services, or

Table D.3: Main information barriers faced

by SMEs in Africa

Information on Average %

Trade contacts and business opportunities 69

Relevant regulations 41

Export support measures 41

Target markets 34

Others 2

Source: Adapted from WTO and ITC (2014), based on CPCCAF survey

data.

93

D. TRADE OBSTACLES

TO SMEs’ PARTICIPATION

IN TRADE

LEVELLING THE TRADING FIELD FOR SMES

downloading platforms through licensing arrangements.

For this reason, it is important to ensure that an effective

solution is chosen. Alternatively, SMEs may decide to

be creative. For example, in e-commerce “while larger

businesses like the online retailer Ozon.ru may choose

to build their own distribution networks, this option is

out of reach for micro and small businesses that may

need to explore other innovative solutions, e.g. the

motorbike delivery system used in Viet Nam. Out-of-

home delivery – involving collection points, delivery

at work, parcel lockers and in-store pickup – is one

option to increase the attractiveness of e-commerce in

developing countries” (UNCTAD, 2015).

The support of intermediaries in a distribution channel

is most often used by companies that cannot sell

products by themselves. Although direct contact with

clients helps to establish prices, the participation of an

intermediary ensures that the product will be provided

more efficiently by means of their networks, contacts,

experience, specialization or lower costs borne by the

intermediary. For example, some intermediaries hold

directories of potential clients and/or (specialized)

distribution firms, conduct in-country market research,

help to address language barriers (e.g. via translation

services), or offer assistance for travel arrangements or

follow-up support. For SMEs, direct contact with clients

has traditionally been seen as more effective than use

of intermediaries in the distribution channel, and this

is particularly true for services, with which exclusive

distribution strategies, a single product, clearly defined

clients and episodic sales are the rule. When it comes

to exporting its products, this “direct” model may be

more difficult to implement for SMEs, in particular if

they want to reach a wider set of clients. For SMEs,

using go-between services reduces the portion of

tasks that they would do themselves if they decided not

to use such intermediaries.

20

It also reduces part of the

associated risks or clients’ fears, by providing advice/

interactivity, trust with payments, or the perception

that purchases are not so complex. In addition, using

intermediaries may be a lighter solution for SMEs than

establishing affiliates in services (or eventually goods)

export markets, unless the size of business is big

enough to justify such an establishment.

In the context of distribution networks, marketing

through the Internet (e.g. through the use of search

engines) or email, social networking platforms (e.g.

Facebook) and e-commerce have had an important

role in recent years. Whether using the direct channel

(i.e. direct sales of producers to clients) or indirect

means (i.e. intermediaries), these distribution network

instruments have enabled a greater participation of

SMEs in international trade by increasing the visibility

of their products and allowing the establishment of

links with clients in potential overseas markets (see

Section D.4 below). They have also helped enterprises,

in particular SMEs, to obtain information more easily on

foreign markets (e.g. analytical solutions such as those

offered by search engines or e-commerce companies),

as well as to access information on regulatory matters

or standards. Finally, these distribution networks have

assisted SMEs to obtain information on the network

itself, to understand how best they can approach clients

(i.e. via the ideal agent/dealer/distributor, payment

systems, marketing resources, shipping and receiving

logistics, etc.).

(b) Transport and logistics

Trade logistics goes beyond shipping goods across

borders; it covers a wide range of services from

the pick-up of goods, consolidation of shipment,

procurement of transportation, customs clearance,

warehousing and distribution, to the delivery of goods

to final consumers. SMEs often lack international

freight shipment experiences, and their cargos are

usually smaller and of more irregular frequency. SMEs’

imports and exports therefore rely on services provided

by logistics providers.

Compared to big firms, SMEs face particular logistics

challenges arising from higher logistics costs and the

inability of accessing efficient logistics services, which

are two sides of the same coin. This is even more the

case for SMEs in developing countries, due to poor

logistics infrastructure and underdeveloped logistics

markets. The World Bank Logistics Performance

Index consistently shows that logistics costs in low-

performance countries (mainly developing countries)

are higher than in high-performance countries (mainly

developed countries). Logistics challenges constitute

an important impediment to SMEs’ participation in

trade.

SMEs trade smaller quantities than big enterprises do.

This implies that fixed trade costs, including logistics

costs, often make up a greater share of the unit cost

of their goods when compared to rivals exporting

larger volumes. In other words, logistics tend to cost

more for SMEs than for large enterprises. For example,

in Latin America, domestic logistics costs, including

stock management, storage, transport and distribution,

can add up to more than 42 per cent of total sales for

SMEs, as compared to 15-18 per cent for large firms.

In Nicaragua, logistics costs for small beef producers,

from farm to abattoir, are more than double of what they

are for large producers. For a small exporter to move a

kilogramme of tomatoes from a Costa Rican farm to

the final point of sale in Managua, Nicaragua, transport

represents the main cost, at almost a quarter of the total

cost (23 per cent), followed by customs (11 per cent)

and taxes (6 per cent). In contrast, for large exporters,

WORLD TRADE REPORT 2016

94

the main costs are customs (10 per cent), followed by

transport (6 per cent) and taxes (5 per cent) (OECD,

2014). Hence, reducing logistics costs is crucial for the

improvement of SMEs’ trade opportunities.

Geographical distance clearly affects SMEs’

participation on export. Evidence shows that, compared

to large firms, SMEs are discouraged from entering

distant markets. For instance, research conducted

on French firms indicates that small firms export on

average 3.7 per cent less to export destinations that

are 10 per cent further away from France. For those

SMEs exporting to distant markets, the average

shipments per product and per firm are greater in order

to overcome the transportation costs.

According to a study undertaken by the USITC (USITC,

2014), the low reliability and high costs of shipping

represent significant barriers for US-based SMEs’

exporting to the European Union. Cost and reliability

problems of EU postal systems have forced companies to

use private couriers for shipping, which results in higher

costs that are harder for small businesses to absorb.

Shipping costs are also a major obstacle for EU SMEs’

exports to the United States, “because of the distance

to the US market, business owners are concerned that

the cost of transportation will increase the price of their

products to a point where they can no longer compete

with products manufactured locally” (UPS, 2014).

In order to reduce logistics costs, firms (especially

big manufacturers or big retailers) tend to outsource

logistics functions (transport, warehousing, inventory

management, freight forwarding, etc.) to specialized

providers, i.e. providers of “third-party logistics” (3PL).

“Outsourcing in logistics is a sign of strong logistics

performance and of a mature logistics market, and

is often a direct marker of logistics sophistication”

(World Bank, 2014). Partnerships with 3PL providers

not only allow firms to focus on their core business;

it also means access to advanced logistics services

and supply chain management. Advanced logistics

services are ICT-intensive and adapt quickly to new

technologies, which often require the integration of

supply chain management platforms with customers’

internal systems. Due to resource constraints, SMEs

often lag behind in adapting to technological advances

and are reluctant to tap into the 3PL market. The small

size of their businesses is also a disadvantage for SMEs

wishing to negotiate affordable contracts with 3PL.

21

SMEs face disproportionally high logistics costs

(Straube et al., 2013). For manufacturing firms with

less than 250 employees, on average their logistics

costs account for 14.7 per cent of their overall revenue.

Conversely, firms with more than 1,000 employees

state that the logistics costs only account for 6.7 per

cent of their total revenue. This figure is similar for firms

with 250 to 1,000 workers, which report that logistics

costs account for 6.4 per cent of their total revenue.

The research includes 113 industrial firms across the

world, and the break-up figures on regional or national

levels affirm the above findings. For example, in China,

SMEs reported spending 15 per cent of their overall

revenue on logistics costs, whereas large firms (more