UNITED STATES TRADE REPRESENTATIVE

2022 National Trade Estimate Report on

FOREIGN TRADE

BARRIERS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) is responsible for the preparation of this

report. U.S. Trade Representative Katherine C. Tai gratefully acknowledges the contributions of all USTR

staff to the writing and production of this report and notes, in particular, the contributions of Mitchell

Ginsburg, David Oliver, Russell Smith, and Spencer Smith.

Thanks are extended to partner Executive Branch members of the Trade Policy Staff Committee (TPSC).

The TPSC is composed of the following Executive Branch entities: the Departments of Agriculture, State,

Commerce, Defense, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Interior, Justice,

Transportation, and Treasury; the Environmental Protection Agency; the Office of Management and

Budget; the Council of Economic Advisers; the Council on Environmental Quality; the U.S. Agency for

International Development; the Small Business Administration; the National Economic Council; the

National Security Council; and, the Office of the United States Trade Representative; as well as non-voting

member the U.S. International Trade Commission. In preparing the report, substantial information was

solicited from U.S. Embassies.

Office of the United States Trade Representative

Ambassador Katherine C. Tai

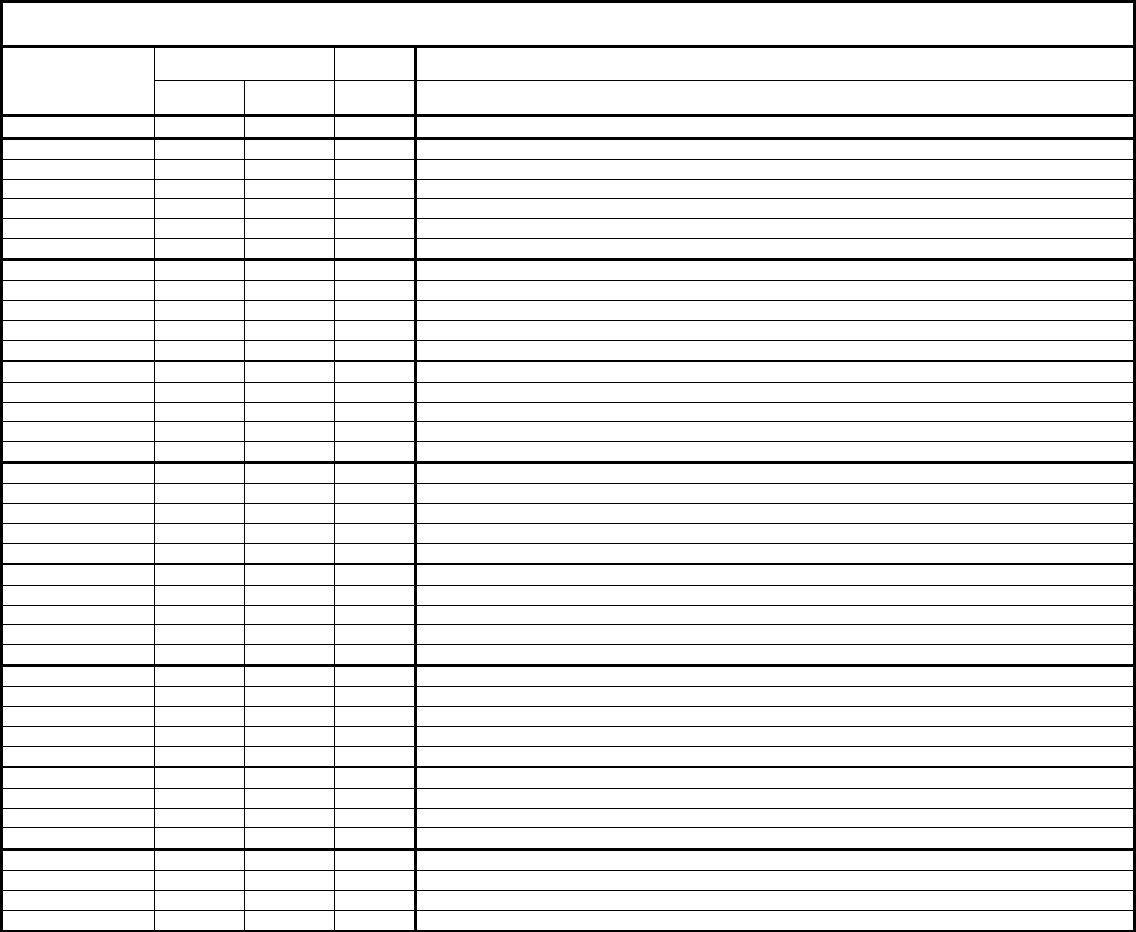

LIST OF FREQUENTLY USED ACRONYMS

APHIS……………………………………...………… Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service,

U.S. Department of Agriculture

CVA ............................................................................. WTO Customs Valuation Agreement

DOL ............................................................................. U.S. Department of Labor

EU

1

............................................................................... European Union

FTA…………………………………………………... Free Trade Agreement

GATT ........................................................................... General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

GATS ........................................................................... General Agreement on Trade in Services

GI ................................................................................. Geographical Indication

GPA ............................................................................. WTO Agreement on Government Procurement

HS ................................................................................ Harmonized System

HTS .............................................................................. Harmonized Tariff Schedule

ICT ............................................................................... Information and Communication Technology

IP .................................................................................. Intellectual Property

MFN ............................................................................. Most-Favored-Nation

MOU ............................................................................ Memorandum of Understanding

MRL ............................................................................. Maximum Residue Limit

SBA .............................................................................. U.S. Small Business Administration

SME ............................................................................. Small and Medium-Sized Enterprise

SPS ............................................................................... Sanitary and Phytosanitary

TBT .............................................................................. Technical Barriers to Trade

TFA .............................................................................. Trade Facilitation Agreement

TIFA ............................................................................. Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

TRQ ............................................................................. Tariff-Rate Quota

USAID ......................................................................... U.S. Agency for International Development

USDA ........................................................................... U.S. Department of Agriculture

USTR ........................................................................... United States Trade Representative

VAT………………………………………………….. Value-Added Tax

WTO ............................................................................ World Trade Organization

1

Unless specified otherwise, all references to the European Union refer to the EU-27.

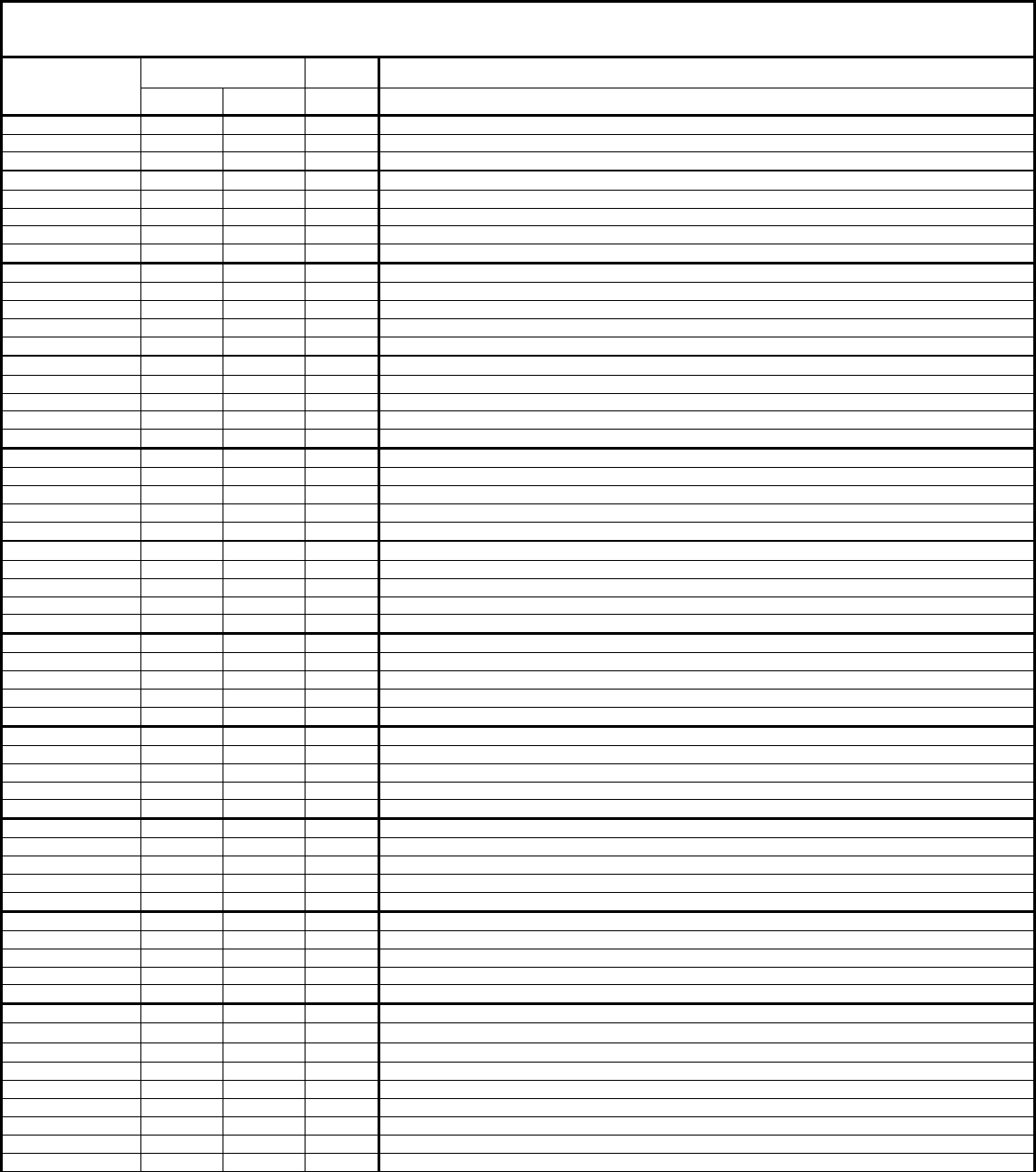

TABLE OF CONTENTS

FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................ 1

ALGERIA ..................................................................................................................................................... 5

ANGOLA ...................................................................................................................................................... 9

ARAB LEAGUE ........................................................................................................................................ 15

ARGENTINA ............................................................................................................................................. 21

AUSTRALIA .............................................................................................................................................. 35

BAHRAIN .................................................................................................................................................. 39

BANGLADESH ......................................................................................................................................... 43

BOLIVIA .................................................................................................................................................... 53

BRAZIL ...................................................................................................................................................... 57

BRUNEI DARUSSALAM ......................................................................................................................... 69

CAMBODIA ............................................................................................................................................... 73

CANADA ................................................................................................................................................... 77

CHILE ......................................................................................................................................................... 85

CHINA ........................................................................................................................................................ 89

COLOMBIA ............................................................................................................................................. 129

COSTA RICA ........................................................................................................................................... 135

COTE D’IVOIRE ..................................................................................................................................... 141

DOMINICAN REPUBLIC ....................................................................................................................... 147

ECUADOR ............................................................................................................................................... 151

EGYPT ...................................................................................................................................................... 161

EL SALVADOR ....................................................................................................................................... 167

ETHIOPIA ................................................................................................................................................ 173

EUROPEAN UNION ............................................................................................................................... 179

GHANA .................................................................................................................................................... 227

GUATEMALA ......................................................................................................................................... 235

HONDURAS ............................................................................................................................................ 239

HONG KONG .......................................................................................................................................... 243

INDIA ....................................................................................................................................................... 245

INDONESIA ............................................................................................................................................. 267

ISRAEL .................................................................................................................................................... 285

JAPAN ...................................................................................................................................................... 287

JORDAN ................................................................................................................................................... 305

KENYA .................................................................................................................................................... 309

KOREA ..................................................................................................................................................... 317

KUWAIT .................................................................................................................................................. 329

LAOS ........................................................................................................................................................ 333

MALAYSIA ............................................................................................................................................. 337

MEXICO ................................................................................................................................................... 345

MOROCCO .............................................................................................................................................. 357

NEW ZEALAND ...................................................................................................................................... 361

NICARAGUA........................................................................................................................................... 363

NIGERIA .................................................................................................................................................. 371

NORWAY................................................................................................................................................. 379

OMAN ...................................................................................................................................................... 383

PAKISTAN ............................................................................................................................................... 387

PANAMA ................................................................................................................................................. 395

PARAGUAY ............................................................................................................................................ 399

PERU ........................................................................................................................................................ 403

THE PHILIPPINES .................................................................................................................................. 407

QATAR ..................................................................................................................................................... 417

RUSSIA .................................................................................................................................................... 421

SAUDI ARABIA ...................................................................................................................................... 443

SINGAPORE ............................................................................................................................................ 451

SOUTH AFRICA...................................................................................................................................... 455

SWITZERLAND ...................................................................................................................................... 463

TAIWAN .................................................................................................................................................. 467

THAILAND .............................................................................................................................................. 477

TUNISIA .................................................................................................................................................. 487

TURKEY .................................................................................................................................................. 491

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES ................................................................................................................... 501

UKRAINE................................................................................................................................................. 509

UNITED KINGDOM ............................................................................................................................... 517

URUGUAY............................................................................................................................................... 525

VIETNAM ................................................................................................................................................ 527

APPENDIX I: REPORT ON PROGRESS IN REDUCING TRADE-RELATED BARRIERS TO THE

EXPORT OF GREENHOUSE GAS INTENSITY REDUCING TECHNOLOGIES

APPENDIX II: U.S. TRADE DATA FOR SELECT TRADE PARTNERS IN RANK ORDER OF U.S.

EXPORTS, 2020-2021

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 1

FOREWORD

SCOPE AND COVERAGE

The 2022 National Trade Estimate Report on Foreign Trade Barriers (NTE) is the 37th report in an annual

series that highlights significant foreign barriers to U.S. exports, U.S. foreign direct investment, and U.S.

electronic commerce. This document is a companion piece to the President’s 2022 Trade Policy Agenda

and 2021 Annual Report, published by the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) on

March 1, 2022.

In accordance with section 181 of the Trade Act of 1974, as amended by section 303 of the Trade and Tariff

Act of 1984 and amended by section 1304 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, section

311 of the Uruguay Round Trade Agreements Act, and section 1202 of the Internet Tax Freedom Act,

USTR is required to submit to the President, the Senate Finance Committee, and appropriate committees

in the House of Representatives, an annual report on significant foreign trade barriers. The statute requires

an inventory of the most important foreign barriers affecting U.S. exports of goods and services, including

agricultural commodities and U.S. intellectual property; foreign direct investment by U.S. persons,

especially if such investment has implications for trade in goods or services; and U.S. electronic commerce.

Such an inventory enhances awareness of these trade restrictions, facilitates U.S. negotiations aimed at

reducing or eliminating these barriers, and is a valuable tool in enforcing U.S. trade laws and strengthening

the rules-based system.

The NTE Report is based upon information compiled within USTR, the Departments of Commerce and

Agriculture, other U.S. Government agencies, and U.S. Embassies, as well as information provided by the

public in response to a notice published in the Federal Register

.

This Report discusses key export markets for the United States, covering 60 countries; the European Union;

Taiwan; Hong Kong, China; and, the Arab League. As always, omission of particular countries and barriers

does not imply that they are not of concern to the United States.

The NTE Report covers significant barriers, whether they are consistent or inconsistent with international

trading rules. Tariffs, for example, are an accepted method of protection under the General Agreement on

Tariffs and Trade 1994. Even a very high tariff does not violate international rules unless a country has

made a commitment not to exceed a specified rate, i.e., a tariff binding. Nonetheless, it would be a

significant barrier to U.S. exports, and therefore covered in the NTE Report. Measures not consistent with

international trade agreements, in addition to serving as barriers to trade and causes of concern for policy,

are actionable under U.S. trade law as well as through the World Trade Organization and free trade

agreements. Since early 2020, there were significant trade disruptions as a result of temporary trade

measures taken directly as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Trade barriers elude fixed definitions, but may be broadly defined as government laws and regulations or

government-imposed measures, policies, and practices that restrict, prevent, or impede the international

exchange of goods and services; protect domestic goods and services from foreign competition; artificially

stimulate exports of particular domestic goods and services; fail to provide adequate and effective

protection of intellectual property rights; unduly hamper U.S. foreign direct investment or U.S. electronic

commerce; or impose barriers to cross-border data flows. The recent proliferation of data localization and

other such restrictive technology requirements is of particular concern to the United States.

2 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

The NTE Report classifies foreign trade barriers in 14 categories, as follows:

• Import policies (e.g., tariffs and other import charges, quantitative restrictions, import

licensing, pre-shipment inspection, customs barriers and shortcomings in trade facilitation or

in valuation practices, and other market access barriers);

• Technical barriers to trade (e.g., unnecessarily trade restrictive or discriminatory standards,

conformity assessment procedures, labeling, or technical regulations, including unnecessary or

discriminatory technical regulations or standards for telecommunications products);

• Sanitary and phytosanitary measures (e.g., measures applied to protect food safety, or animal

and plant life or health that are unnecessarily trade restrictive, discriminatory, or not based on

scientific evidence);

• Government procurement (e.g., closed bidding and bidding processes that lack transparency);

• Intellectual property protection (e.g., inadequate patent, copyright, and trademark regimes;

trade secret theft; and inadequate enforcement of intellectual property rights);

• Services barriers (e.g., prohibitions or restrictions on foreign participation in the market,

discriminatory licensing requirements or standards, local presence requirements, and

unreasonable restrictions on what services may be offered);

• Digital trade and electronic commerce (e.g., barriers to cross-border data flows, including data

localization requirements, discriminatory practices affecting trade in digital products,

restrictions on the provision of Internet-enabled services, and other restrictive technology

requirements);

• Investment barriers (e.g., limitations on foreign equity participation and on access to foreign

government-funded research and development programs, local content requirements,

technology transfer requirements, export performance requirements, and restrictions on

repatriation of earnings, capital, fees and royalties);

• Subsidies, especially export subsidies (e.g., subsidies contingent upon export performance and

agricultural export subsidies that displace U.S. exports in third country markets) and local

content subsidies (e.g., subsidies contingent on the purchase or use of domestic rather than

imported goods);

• Competition (e.g., government-tolerated anticompetitive conduct of state-owned or private

firms that restricts the sale or purchase of U.S. goods or services in the foreign country’s

markets or abuse of competition laws to inhibit trade; fairness and due process concerns by

companies involved in competition investigatory and enforcement proceedings in the country);

• State-owned enterprises (e.g., subsidies to and from industrial state-owned enterprises involved

in the manufacture or production of non-agricultural goods or in the provision of services, as

well as industrial state-owned enterprises that could contribute to overcapacity, or

discriminating against foreign goods or services, acting inconsistently with commercial

considerations in the purchase and sale of goods and services);

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 3

• Labor (e.g., concerns with failures by a government to protect internationally recognized

worker rights, including through failure to eliminate forced labor, or failures to eliminate

discrimination in respect of employment or occupation);

• Environment (e.g., concerns with a government’s levels of environmental protection,

unsustainable stewardship of natural resources, and harmful environmental practices); and

• Other barriers (e.g., barriers that encompass more than one category, such as bribery and

corruption, or that affect a single sector).

The prevalence of corruption is a consistent complaint from U.S. firms that trade with or invest in other

economies. Corruption takes many forms and affects trade and development in different ways. In many

countries and economies, it affects customs practices, licensing decisions, and the award of government

procurement contracts. If left unchecked, bribery and corruption can negate market access gained through

trade negotiations, frustrate broader reforms and economic stabilization programs, and undermine the

foundations of the international trading system. Corruption also hinders development and contributes to

the cycle of poverty. The Foreign Corrupt Practices Act prohibits U.S. companies from bribing foreign

public officials, and numerous other domestic laws discipline corruption of public officials at the State and

Federal levels. The United States continues to play a leading role in addressing bribery and corruption in

international business transactions and has made real progress over the past quarter century building

international coalitions to fight bribery and corruption.

Pursuant to Section 1377 of the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988, USTR annually reviews

the operation and effectiveness of U.S. telecommunications trade agreements to make a determination on

whether any foreign government that is a party to one of those agreements is failing to comply with that

government’s obligations or is otherwise denying, within the context of a relevant agreement, “mutually

advantageous market opportunities” to U.S. telecommunication products or services suppliers. The NTE

Report highlights both ongoing and emerging barriers to U.S. telecommunication services and goods

exports from the annual review called for in Section 1377.

TRADE IMPACT OF FOREIGN BARRIERS

Trade barriers or other trade distorting practices affect U.S. exports to a foreign market by effectively

imposing costs on such exports that are not imposed on goods produced in the importing market. Estimating

the impact of a foreign trade measure on U.S. exports of goods requires knowledge of the additional cost

the measure imposes on them, as well as knowledge of market conditions in the United States, in the foreign

market imposing the measure, and in third country markets. In practice, such information often is not

available.

In theory, where sufficient data exist, an approximate impact of tariffs on U.S. exports could be derived by

obtaining estimates of supply and demand price elasticities in the importing market and in the United States.

Typically, the U.S. share of imports would be assumed constant. When no calculated price elasticities are

available, reasonable postulated values would be used. The resulting estimate of lost U.S. exports would

be approximate, depend on the assumed elasticities, and would not necessarily reflect changes in trade

patterns with third country markets. Similar procedures might be followed to estimate the impact of

subsidies that displace U.S. exports in third country markets.

The estimation of the impact of non-tariff measures on U.S. exports is far more difficult, since no readily

available estimate exists of the additional cost these restrictions impose. Quantitative restrictions or import

licenses limit (or discourage) imports and thus are likely to raise domestic prices, much as a tariff does.

However, without detailed information on price differences between markets and on relevant supply and

4 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

demand conditions, it would be difficult to derive the estimated effects of these measures on U.S. exports.

Similarly, it would be difficult to quantify the impact on U.S. exports (or commerce) of other foreign

practices, such as government procurement policies, nontransparent standards, or inadequate intellectual

property rights protection.

The same limitations apply to estimates of the impact of foreign barriers to U.S. services exports.

Furthermore, the trade data on services exports are extremely limited in detail. For these reasons, estimates

of the impact of foreign barriers on trade in services also would be difficult to compute. With respect to

investment barriers, no accepted techniques for estimating the impact of such barriers on U.S. investment

flows exist. The same caution applies to the impact of restrictions on electronic commerce.

To the extent possible, the NTE Report endeavors to present estimates of the impact on U.S. exports, U.S.

foreign direct investment, or U.S. electronic commerce of specific foreign trade barriers and other trade

distorting practices. In some cases, stakeholder valuations estimating the effects of barriers may be

contained in the NTE Report. The methods for computing these valuations are sometimes uncertain.

Hence, their inclusion in the NTE Report should not be construed as a U.S. Government endorsement of

the estimates they reflect. Where government-to-government consultations related to specific foreign

practices were proceeding at the time of this NTE Report’s publication, estimates were excluded, in order

to avoid prejudice to these consultations.

March 2022

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 5

ALGERIA

TRADE AGREEMENTS

The United States–Algeria Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

The United States and Algeria signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) on July 13,

2001. This Agreement is the primary mechanism for discussions of trade and investment issues between

the United States and Algeria.

IMPORT POLICIES

Tariffs and Taxes

Tariffs

Algeria is not a Member of the World Trade Organization (WTO). Goods imported into Algeria currently

face a range of tariffs, from zero percent to 200 percent.

Algeria’s average Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) applied tariff rate was 18.9 percent in 2019 (latest data

available). Algeria’s average MFN applied tariff rate was 23.6 percent for agricultural products and 18.2

percent for non-agricultural products in 2019 (latest data available). Nearly all finished manufactured

products, dried distillers grains, and corn gluten feed entering Algeria are subject to a 30 percent tariff rate,

but some limited categories are subject to a 15 percent rate. Goods facing the highest rates are those for

which equivalents are currently manufactured in Algeria. In January 2019, citing the need to encourage

local production and ease pressure on the country’s foreign exchange reserves, Algeria implemented new

temporary additional safeguard duties (DAPs) of 30 percent to 200 percent (the higher rate applies only to

ten cement tariff lines under the Harmonized System heading 25.23) on a list of more than 1,000

manufactured and agricultural goods. The few items that remain duty free are generally European Union

(EU)-origin goods that are used in manufacturing and are exempt from tariffs under the 2006 EU–Algeria

Association Agreement. The original DAP list was revised in April 2019 to exempt a number of food- and

agriculture-related products including tree nuts, peanuts, butter, dried fruits, and fresh or chilled beef. That

list remains in effect, though the government announced in January 2022 that it would double it (details to

be released separately), while still describing it as ‘temporary.’

Taxes

Most imported goods are subject to the 19.0 percent value-added tax (VAT), and an additional 0.3 percent

tax is levied on a good if the applicable customs value exceeds Algerian dinars (DZD) 20,000

(approximately $148).

Non-Tariff Barriers

Import Bans and Import Restrictions

Since January 2009, Algeria’s Ministry of Health has restricted the import of a number of generic

pharmaceutical products and medical devices. In 2015, the Ministry of Health published the most recent

list of 357 generic pharmaceutical products whose importation is prohibited. Since 2007, the Algerian

Government has banned the import of used medical equipment without a special exception. Algeria has

applied the regulation broadly to block the re-importation of machinery sent abroad for maintenance under

6 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

warranty, even for equipment owned by state-run hospitals. In May 2020, Algeria issued a decree to exempt

customs duties and VAT for medical devices, pharmaceutical products, and testing equipment imported to

combat the COVID-19 pandemic. Algeria renewed the decree in May 2021.

Beyond medical devices, Algeria bans most types of used machinery from entry, except for refurbished

assembly line equipment used in domestic industries.

In February 2021, the Ministry of Commerce issued a new schedule for 2021 that established a separate

seasonal ban for each agricultural product. The new schedule adjusted a year-round restriction on almond

imports to a seasonal ban from June to August 2021. In September 2021, the Algerian Government

restricted the import of animal products such as tuna, yogurt, ice cream, liquid egg yolks, lamb’s wool and

camel hair, corned beef, live bait for fishing, and non-food products such as baseball bats. In October 2021,

Algeria restricted the import of products falling under the tariff heading of “other,” which includes products

that are not classified within a certain category and products for which there is minimal demand. Algeria

justified these decisions as necessary to reduce the country’s import bill and combat fraud.

The Ministry of Finance instructed banks, in August 2021, to suspend the processing of accounts for

importers of products intended for resale starting at the end of October 2021 unless importers complied

with a March 2021 decree requiring them to update their import registration to include only one category

of product per company. The Ministry subsequently communicated implementation instructions to the

Ministry of Commerce’s National Center of Commerce Registry (CNRC), but not to importers themselves.

Importers must approach individually to seek guidance regarding their particular situation, rather than rely

on publicly available information. The stated goal of this process is to reduce the number of importers from

15,000 to 9,000, according to the Minister of Commerce in October 2021.

Quantitative Restrictions

In August 2020, Algeria released a new Book of Specifications concerning the automotive industry,

replacing the previous automotive regulatory regime established in 2017. As of March 2022, the Algerian

Government has not granted any company authorization to import under the new regime. The new Book

of Specifications covers automobiles, buses, trucks, and construction equipment, and establishes an import

quota of up to 200,000 vehicles per year, with an annual cap of $2 billion. Due to customs, VAT, and other

taxes, vehicles cost more than double the market rates when purchased by individuals overseas and

imported. While the import quota on automobile kits for assembly of passenger vehicles is currently set at

zero, the new regulation indicated that the Algerian Government would set a new quota for automotive

companies that receive authorization to engage in local assembly or manufacturing. No new cars for sale

in dealerships have been imported into Algeria since the 2020 regime was announced. A provision in the

June 2021 Complementary Finance Law permits Algerians to import used cars which are three years old or

less, though purchasers will be required to use their own foreign currency.

Algeria has established a maximum import volume of four million metric tons of bread (common) wheat,

accounting for nearly two-thirds of annual average imports. The Algerian President announced in August

2021 that moving forward, the state grains agency (OAIC) will be the country’s exclusive wheat importer,

so as to counteract alleged “illicit practices” by private importers. However, the Algerian Government had

not implemented this policy as of March 2022.

Customs Barriers and Trade Facilitation

Clearing goods through Algerian Customs is the most frequently reported problem facing companies.

Delays can take weeks or months, in many cases without explanation. In addition to a certificate of origin,

the Algerian Government requires all importers to provide certificates of conformity and quality from an

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 7

independent third party. Algerian Customs requires shipping documents be stamped with a “Visa Fraud”

note from the Ministry of Commerce, indicating that the goods have passed a fraud inspection before the

goods are cleared. Many importations also require authorizations from multiple ministries, which

frequently causes additional bureaucratic delays, especially when the regulations do not clearly specify

which ministry’s authority is being exercised. Storage fees at Algerian ports of entry are high and the fees

double when goods are stored for longer than 10 days.

Regulations introduced in October 2017 require importers to deposit with a bank a financial guarantee equal

to 120 percent of the cost of the import 30 days in advance, which especially burdens small and medium-

sized importers that often lack sufficient cash flow.

SANITARY AND PHYTOSANITARY BARRIERS

Algeria bans the production, importation, distribution, or sale of seeds that are the products of

biotechnology. There is an exception for biotechnology seeds imported for research purposes.

In 2020, U.S. and Algerian authorities finalized export certificates for chicken-hatching eggs, day-old

chicks, and bovine embryos. U.S. and Algerian veterinary authorities continue to engage in negotiations

on export certificates to allow for the importation of U.S. bovine semen, beef cattle, dairy breeding cattle,

and beef and poultry meat and meat products.

Algeria maintains strict animal health certificates for animals and animal products, dairy and dairy products,

as well as processed products of animal origin.

GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT

Algeria announced in August 2015 that all ministries and state-owned enterprises would be required to

purchase domestically manufactured products whenever available. It further announced that the

procurement of foreign goods would be permitted only with special authorization at the ministerial level

and if a locally made product could not be identified. Algeria requires approval from the Council of

Ministers for expenditures in foreign currency that exceed DZD 10 billion (approximately $74 million).

In 2017, this requirement delayed payments to at least one U.S. company.

As Algeria is not a Member of the WTO, it is neither a Party to the WTO Agreement on Government

Procurement nor an observer to the WTO Committee on Government Procurement.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION

Algeria was moved from the Priority Watch List to the Watch List in the 2021 Special 301 Report

. Algeria

has taken some positive steps to improve intellectual property (IP) protection and enforcement, including

by increasing coordination on IP enforcement and engaging in capacity building and training efforts.

However, concerns remain, including regarding the lack of an effective mechanism for the early resolution

of potential pharmaceutical patent disputes, inadequate judicial remedies in cases of patent infringement,

the lack of administrative opposition in Algeria’s trademark system, and the need to increase enforcement

efforts against counterfeiting and piracy. In addition, Algeria does not provide an effective system for

protecting against the unfair commercial use, as well as unauthorized disclosure, of undisclosed test or other

data generated to obtain marketing approval for pharmaceutical products.

8 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

BARRIERS TO DIGITAL TRADE AND ELECTRONIC COMMERCE

In May 2018, Algeria enacted a law requiring electronic commerce platforms conducting business in

Algeria to register with the government and to host their websites from a data center located in Algeria.

Such localization requirements impose unnecessary costs on service suppliers by requiring redundant

storage systems. Such requirements are disproportionately burdensome for small firms.

Algeria permits citizens to purchase goods from outside the country using international credit cards, with a

maximum value per transaction of DZD100,000 (approximately $740). Algerian foreign exchange

regulations prohibit the use of certain online payment processors to transfer money from one account to

another.

INVESTMENT BARRIERS

Prior to 2020, Algeria’s investment law required Algerian ownership of at least 51 percent in all projects

involving foreign investments (known as the 51/49 rule). This restriction was lifted in 2020. However, the

2021 Finance Law re-imposed the 51 percent requirement––with retroactive application to foreign

companies already established in Algeria and owning more than 49 percent of operations––on activities

involving raw materials; products and goods imported for resale in the same condition (subsequently these

products have been exempted from the requirement); as well as for companies in the strategic sectors of

mining, upstream energy activities, industries related to the military, transportation infrastructure, and

pharmaceutical production. As there is no single process for registering foreign investments, prospective

investors must work with the ministry or ministries relevant to a particular project to negotiate, register,

and set up their businesses. U.S. businesses have commented that the process is subject to political

influence and that a lack of transparency in the decision-making process makes it difficult to determine the

reasons for any delays.

The 2020 Book of Specifications for the automotive industry increased domestic content requirements in

production. Minimum domestic content integration rates for domestic assembly plants are now 30 percent

in the first year, 35 percent after three years, 40 percent after four years, and 50 percent after five years.

Additionally, the Book of Specifications mandates that automotive importers be 100 percent Algerian-

owned, and retroactively excludes foreign companies from holding ownership stakes in importation

companies and dealerships.

STATE-OWNED ENTERPRISES

State-owned enterprises (SOEs) comprise about two-thirds (by market value) of the Algerian economy.

The national oil and gas company Sonatrach is the most prominent SOE, but SOEs are present in all sectors

of the economy. SOEs leverage their position in the market to gain advantage over privately-owned

competitors. For example, state-owned telecommunications provider Algerie Telecom holds a monopoly

over all undersea data cable traffic in and out of Algeria, offering services at a considerable advantage over

private companies operating in the telecommunications sector.

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 9

ANGOLA

TRADE AGREEMENTS

The United States–Angola Trade and Investment Framework Agreement

The United States and Angola signed a Trade and Investment Framework Agreement (TIFA) on May 19,

2009. This Agreement is the primary mechanism for discussions of trade and investment issues between

the United States and Angola.

IMPORT POLICIES

Tariffs and Taxes

Tariffs

Angola’s average Most-Favored-Nation (MFN) applied tariff rate for all products was 10.2 percent in 2019

(latest data available). Angola’s average MFN applied tariff rate was 19.3 percent for agricultural products

and 8.7 percent for non-agricultural products in 2019 (latest data available). Angola has bound 100 percent

of its tariff lines in the World Trade Organization (WTO), with an average WTO bound tariff rate of 59.1

percent, and average bound rates of 52.7 percent for agricultural products, and 60.1 percent for non-

agricultural products.

Revised customs measures entered into force in August 2018. These measures exempt imports of

household products, medicines, and hospital equipment from tariffs. They assign minimum tax and customs

duty rates for the import of essential goods and other goods not locally manufactured. Medicines,

educational materials (i.e., schoolbooks), and automotive parts imported by automotive assembly investors

in Angola remain exempted from customs duties under this regime.

In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, Angola has allowed all medicines and biosafety material to be

imported duty free.

Taxes

In October 2019, Angola introduced a 14 percent value-added tax (VAT) and revoked a 10 percent

consumer tax previously imposed on all products, domestic and imported, albeit with numerous product

and service exemptions. In August 2020, the Government of Angola decreased the VAT for certain

agricultural products.

Law No. 42/20, approving the 2021 State Budget, entered into force January 1, 2021. The law introduced

a new VAT – the Simplified VAT Regime – which applies to taxpayers whose annual turnover and import

operations for the previous 12 months was approximately $580,000 or less.

The law also increased the taxable basis of some imported goods, especially luxury products, by specifying

that the VAT will be charged based on an amount that includes duties, taxes, and ancillary expenses, among

others. Separately, the law reduced from 14 percent to 5 percent the VAT applied to the import and supply

of certain goods, including food stuffs, detergents, and agricultural seeds and raw materials, the latter two

to boost local agricultural production.

10 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

On October 28, 2021, Angola approved the reduction of VAT from 14 percent to 7 percent for additional

items of the basic food basket not covered in Law 42/20. The measure was intended to lower the cost of

28 regularly consumed items that comprise the basic food basket, as well as the cost of industrial and

agricultural production equipment and small- to medium-sized fishing boats, with the goal of boosting

agricultural and fisheries production.

Non-Tariff Barriers

Import Licensing

The importation of certain goods requires authorization from specific government ministries, which can

result in delays and extra costs. Importers must be registered with the Ministry of Commerce for the

category of product they are importing. Only registered companies can apply for an import license, which

is required for imports of sensitive products such as food, medical devices, pharmaceuticals, and

agricultural inputs.

Importers who possess a valid general import license issued by the Ministry of Commerce and a specific

import license issued by the Ministry of Health may import pharmaceuticals products.

Import Restrictions

Presidential Decree No. 23/19, which entered into force in January 2019, appears aimed to restrict the

importation of certain products unless the importer can demonstrate the product is not available

domestically. The Decree currently includes more than 54 products, mainly agricultural goods and applies

to any imports that compete with goods produced in the Luanda-Bengo special economic zone. Impacted

products include poultry, maize flour, and diapers. The United States continues to raise concerns about this

decree with Angola bilaterally and at the WTO Council for Trade in Goods, the WTO Committee on Market

Access, and the WTO Committee on Agriculture.

In 2020, Angola announced that it would stop providing treasury funds for the import of products of high

domestic consumption which Angola has the capacity to produce. However, as of March 2022, the measure

has not been put into effect. The Ministry of Industry and Trade stated this measure, part of the Program

to Support Production, Diversification of Exports and Import Substitution, aims to protect national

production and promote local economic development. The measure focuses on 11 products: sorghum,

millet, beans, peanuts, carrots, garlic, onions, tomatoes, sweet potatoes, bottled water, and dishwashing

soap. Importers may import these items provided they have access to their own sources of foreign

exchange. (For further information see Foreign Exchange section.)

Customs Barriers and Trade Facilitation

Administration of Angola’s customs service has improved in the last few years but remains a barrier to

accessing the market. Importers still express concerns regarding the turnaround time between customs

clearance and market delivery, which averages 38 days. Traders often contract voluntarily for pre-shipment

inspection services from private inspection agencies.

Angola has not yet notified its customs valuation legislation to the WTO, nor has it responded to the

Checklist of Issues that describes how the Customs Valuation Agreement is being implemented.

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 11

TECHNICAL BARRIERS TO TRADE / SANITARY AND PHYTOSANITARY BARRIERS

Technical Barriers to Trade

In January 2021, Angola announced that it will start requiring imports of basic food basket products in bulk

rather than pre-packaged purportedly to save foreign exchange and support the local packaging industry.

On March 17, 2021, Angola published Executive Decree No. 63/21 and it took effect on June 17, 2021.

The decree requires that imports of 15 agricultural and food products be imported in containers of 25-50 kg

and the packaging into retail denominations must be performed in Angola. The decree applies to sugar,

rice, wheat and corn flour, beans, powdered milk, cooking oil, animal feed, coarse and refined salt, wheat

semolina, pork and beef, margarine, and soap, with some exceptions. Industry stakeholders have raised

concerns over the lack of advance consultation with importers or notification to the WTO and have

expressed concern the measure may lead to monopolies in packaging and labeling as well as shortages. The

United States requested Angola to notify the decree to the WTO via the Angola TBT Enquiry Point to allow

for stakeholder comments. However, Angola did not notify the decree, and it went into effect on June 17,

2021. The United States will continue to monitor the implementation of the decree.

Sanitary and Phytosanitary Barriers

Angola has not introduced a risk management scheme for veterinary and sanitary control purposes.

Therefore, consignments of imports classified in Chapters 2 to 23 of the Harmonized System (including

animal and vegetable products and foodstuffs) must be laboratory tested prior to entry into Angola and

accompanied by a health certificate.

Agricultural Biotechnology

Angola does not allow the use of agricultural biotechnology in production, and imports containing

genetically engineered (GE) components are limited to food aid and scientific research. Angola also

prohibits the importation of viable GE grain or seed. The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries requires

importers to present documentation certifying that their goods do not include biotechnology products.

Importation of GE food is permitted when it is provided as food aid, but the product must be milled before

it arrives in Angola. The Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries allows, subject to regulations and controls,

biotechnology imports for scientific research.

GOVERNMENT PROCUREMENT

According to investors, the bidding process for government procurement remains deficient in terms of

transparency and objectivity, and information about government projects and tenders is often not readily

available from authorities. In February 2021, an international port services company filed an appeal at the

Supreme Court of Angola challenging a 20-year multipurpose terminal service contract awarded to a

different company in January 2021. The complainant cited irregularities and changes to the tender

conditions throughout the bidding process.

In an effort to address investor concerns, on December 23, 2020, the Angolan National Assembly approved

Law No. 41/20, revising its Public Procurement Law (PPL) and revoking Law 9/16 of June 2016. The

revised PPL entered into force on January 22, 2021. The revised law seeks to increase transparency in

public resources utilization and to simplify procedures in public works and public services procurement, in

addition to the acquisition of goods by public entities. The most important changes in the law include

encouraging administrative concessions regarding the granting of rights, land or property related to public

works, public services, and exploration of the public domain. The law calls for such contracts to be carried

out though public-private-partnerships. The law also provides that public procurement contract values in

12 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

the amount of at least 500 million Kwanzas (approximately $770,000) or more be approved by the President

of the Republic and submitted to the Tribunal de Contas (Supreme Audit Institution) for oversight.

The law introduced two new procurement procedures. The first is the Dynamic Electronic Procedure, which

provides for the public acquisition of standard goods and services using an electronic platform. Any

interested party that is properly registered may participate. The second spells out the procedure for

emergency procurement, such as those required during a state of calamity or during a pandemic. A punitive

clause for the most serious breaches of contract by an individual or corporation party to such contracts

contains fines ranging from $1,650 to $3,300 for individuals, and $6,600 to $15,300 for corporations.

Through the revised and simplified PPL, Angola seeks to expand local investment and attract more foreign

direct investment. Angola also expects that the PPL will reduce corruption, nepotism, and fraud, while

increasing competitiveness and improving the Angolan business environment. The United States will

monitor implementation and enforcement of the law in light of the continued weak state of institutions and

the lack of necessary technical capacity to implement and enforce laws.

Angola is neither a Party to the WTO Agreement on Government Procurement, nor an observer to the WTO

Committee on Government Procurement.

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY PROTECTION

Although the Angolan National Assembly continues to work to strengthen existing intellectual property

(IP) legislation, the protection and enforcement of IP remains weak. Trade in counterfeit and pirated goods

is widespread. The Ministry of Commerce tracks and monitors the seizures of counterfeit and pirated goods,

but publishes these statistics only on an ad hoc basis. Stakeholders continue to have concerns regarding

delays in the processing of patent applications.

INVESTMENT BARRIERS

The Angolan Government enacted a private investment law in 2018 aimed at facilitating investment. The

law removed the previous requirement that foreign investors identify a local partner with a 35 percent stake

prior to investing in priority sectors, thereby allowing foreign investors to own investments in their entirety.

The law also eliminated minimum levels of foreign direct investment and established firm sunset clauses

for tax incentives. In addition to changes to the legal framework for investment, the government created

the Agency for Private Investment and Exports Promotion, a state-run agency with the goal of facilitating

investment and export processes.

The law, however, does not apply to investment in the petroleum, diamond, and financial sectors, which

remain governed by sector-specific legislation, including requirements to form joint venture partnerships

with local companies and to use Angola-domiciled banks for many services.

Reforms around improving the investment climate for investors are encouraging; however, investors report

that the regulatory and judicial framework of enforcement institutions remains challenging. Reports

indicate that a lack of local judicial capacity to resolve investment disputes is a challenge for foreign

investors.

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 13

OTHER BARRIERS

Bribery and Corruption

Corruption remains prevalent in Angola for reasons including an inadequately trained civil service, a highly

centralized bureaucracy, a lack of funding to improve capacity, and a lack of uniform implement action of

anticorruption laws. “Gratuities” and other facilitation fees often are requested to secure quicker service

and approval. It is common for government officials to have substantial private business interests that are

not publicly disclosed. Likewise, it is difficult to determine the ownership of some Angolan companies

and the ownership structures of banks. Access to investment opportunities and public financing continues

to favor those connected to the government and the ruling party. Laws and regulations regarding conflicts

of interest, though now codified, are yet to be widely implemented or enforced. Some investors report

pressure to form joint ventures with specific Angolan companies believed to have connections to political

figures.

While levels of corruption and bribery have declined, they still exist. The new Criminal Law and Criminal

Procedure Codes (Law No. 38/20 and Law No. 39/20) entered into force in February 2021. Notable changes

include corporate criminal liability, harsh penalties for corruption of public officials, criminalization of

private corruption, and provisions for seizure of proceeds of a crime, among others. The law also contains

provisions that criminalize bribery of national and foreign public officials; seek an appropriate balance

between immunities and the ability to effectively investigate, prosecute, and adjudicate offences; enhance

cooperation within local law enforcement authorities; and designate a central anticorruption authority.

Enforcement of anticorruption laws remains poor. The United States and the international community have

engaged in anticorruption initiatives to help Angola attain its anticorruption objectives. For instance, on

February 16, 2021, the U.S. Department of State opened a competition for a project that supports Angolan

civil society and independent media to increase public awareness and support for anticorruption and

transparency reform.

Export Taxes

In December 2019, a revised customs tariff code entered into force, which among other things eliminated

the five percent export tax on crude ores.

Foreign Exchange

For many years, a leading business challenge in Angola has been the scarcity of foreign exchange, and the

resulting difficulty of foreign investors to repatriate profits and Angolan companies to pay foreign suppliers.

International and domestic companies operating in Angola face significant delays in securing foreign

exchange approval for remittances to cover key operational expenses, including to import goods and

expatriate salaries. Profit and dividend remittances are even more problematic for most companies.

However, since January 2020, oil companies with Angolan exploration and production rights have been

permitted to sell foreign exchange directly to Angolan commercial banks. The decision ended a five-year

policy that ensured that the international oil companies sold $240 million in foreign exchange monthly to

the BNA, which in turn resold to commercial banks in monthly and eventually daily auctions.

In addition, in August 2020, the National Bank of Angola (BNA) issued Notice 17/20, which implemented

new rules and procedures governing foreign exchange transactions applicable to individuals. Among other

amendments, as of September 2020, foreign employees working in Angola must open a local bank account

into which income from their employer will be deposited in local currency; employers may no longer

transfer remunerations to foreign employees’ accounts abroad. However, a foreign employee may purchase

14 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

foreign currency upon presentation of a valid employment agreement and work permit. Under the notice,

Angolan banking institutions should also verify that the employee’s income was transferred by a tax

compliant employer.

In 2021, the BNA issued two notices intended to regulate foreign exchange transactions and procedures.

Notice 4/21 took effect on April 14, 2021, and provides that: (i) import operations are no longer subject to

licensing by the BNA regardless of the relevant settlement period; (ii) the maximum period allowed for

advance payments in import operations is 90 days (reduced from 180 days); and (iii) regardless of the

method of payment, commercial banks will only debit the relevant amount in the importer’s bank account

when the funds are ready to be transferred abroad. The new notice provides greater flexibility in export

operations, and may allow exporters to dispose more freely of revenues from their export operations. This

contrasts with the previous regime, which contained burdensome requirements on the sale and disposition

of foreign currency.

Notice 5/21 took effect on May 14, 2021, and introduces generally more restrictive rules and procedures

for individuals carrying out foreign exchange transactions, with the goal of combating money-laundering

and terrorist financing. Under this notice, foreign exchange transactions may only be carried out: (1) at

the request of customers who have properly opened accounts; (2) if the financial capacity of the originator

is confirmed, to ensure the legitimacy of the possession of the funds used to purchase the foreign currency;

and (3) if the total amount of the requested transaction and the transactions already carried out in the

calendar year are compatible with the originator’s financial capacity. The notice also more than doubles

the cumulative annual limit on foreign exchange transactions carried out by residents, from $120,000 to

$250,000. The BNA may approve exceptions to this limit on a case-by-case basis. Several types of

transactions are not subject to the annual $250,000 limit, including payments for health care, education,

accommodation, transport, and legal services, and certain transfers of funds of foreign exchange residents.

Foreign workers who are not residents are required to deposit their income into an account at a financial

institution registered in Angola. However, the notice establishes an exception for foreign workers in the

oil sector, who may have their remunerations transferred abroad by their employers.

Business Licensing

In October 2021, the National Assembly approved Law No. 26/21, which revoked the Law of Commercial

Activities No. 1/07 of May 2007. Under Law No. 26/21, the authority to license business activity, which

previously rested with the Ministry of Commerce and since July 2021 with provincial governments and

municipal administrations, was transferred to the President. The law also expands business licensing

eligibility. Commercial stakeholders have expressed concern that the transfer of authority could create

dependence on higher governmental powers to authorize commercial activity.

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 15

ARAB LEAGUE

The 22 Arab League members are the Palestinian Authority and the following countries: Algeria, Bahrain,

Comoros, Djibouti, Egypt, Iraq, Kuwait, Jordan, Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania, Morocco, Oman, Qatar,

Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates, and Yemen. The effect of the

Arab League’s boycott of Israeli companies and Israeli-made goods (originally implemented in 1948) on

U.S. trade and investment in the Middle East and North Africa varies from country to country. On occasion,

the boycott can pose a barrier (because of potential legal restrictions) for individual U.S. companies and

their subsidiaries doing business in certain parts of the region. However, efforts to enforce the boycott have

for many years had an extremely limited practical effect overall on U.S. trade and investment ties with

many key Arab League countries. About half of the Arab League members are also Members of the World

Trade Organization (WTO), and are thus obligated to apply WTO commitments to all current WTO

Members, including Israel. To date, no Arab League member, upon joining the WTO, has invoked the right

of non-application of WTO rights and obligations with respect to Israel.

In 2020, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Morocco, and Sudan announced normalization agreements

with Israel. The normalization agreements include an intent to expand formal trade and investment ties,

among other economic operations, between these Arab League countries and Israel. Egypt and Jordan,

having earlier signed peace treaties with Israel, have long engaged in formal bilateral trade with Israel and

publish official statistics regarding that trade. Currently, such statistics from other Arab League members

either are not published at all or are not regularly updated.

The United States has long opposed the Arab League boycott, and U.S. Government officials from a variety

of agencies frequently have urged Arab League member governments to end it. The U.S. Department of

State and U.S. embassies in relevant Arab League host capitals take the lead in raising U.S. concerns related

to the boycott with political leaders and other officials. The U.S. Departments of Commerce and Treasury

and the Office of the United States Trade Representative (USTR) monitor boycott policies and practices of

Arab League members, and, aided by U.S. embassies, lend advocacy support to firms facing boycott-related

pressures.

The Arab League boycott of Israel was the impetus for the creation of U.S. antiboycott authorities during

the 1970s. U.S. antiboycott laws (the 1976 Tax Reform Act (TRA) and the Anti-boycott Act of 2018, Part

II of the Export Control Reform Act of 2018, 50 U.S.C. Sections 4801-4852 (ECRA)), prohibit U.S. firms

from taking certain actions with the intent to comply with foreign boycotts that the United States does not

sanction. As a practical matter, foreign countries’ boycotts of Israel, as reflected in government directives,

laws, and regulations, continue to be the principal boycotts with which U.S. companies are concerned. The

ECRA’s antiboycott provisions are implemented by Part 760 of the Export Administration Regulations, 15

CFR Parts 770-774 (EAR). The Department of Commerce’s Office of Antiboycott Compliance (OAC)

oversees enforcement of Part 760, which prohibits certain types of conduct by U.S. persons (including

businesses) undertaken in support of any unsanctioned foreign boycott maintained by a country against a

country friendly to the United States. Prohibited activities include, inter alia, agreements by U.S.

companies to refuse to do business with a boycotted country, furnishing by U.S. companies of information

about business relationships with a boycotted country, and implementation by U.S. companies of letters of

credit that include boycott terms. The TRA’s antiboycott provisions, administered by the Department of

the Treasury and the Internal Revenue Service, deny certain foreign tax benefits to companies that agree to

requests from boycotting countries to participate in certain types of boycotts.

The U.S. Government’s efforts to oppose the Arab League boycott include alerting appropriate officials in

the boycotting countries to the presence of prohibited boycott requests and the adverse impact of those

requests on U.S. firms and on Arab League members’ ability to expand trade and investment ties with the

16 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

United States. In this regard, OAC officials periodically visit Arab League members to consult with

appropriate counterparts on antiboycott compliance issues. These consultations provide technical

assistance to those counterparts to identify language in commercial documents that may constitute or be

related to prohibited and/or reportable boycott requests under Part 760 of the EAR.

Boycott activity can be classified according to three categories. The primary boycott prohibits the

importation of goods and services from Israel into the territory of Arab League members. This prohibition

may conflict with the obligation of Arab League members that are also Members of the WTO to treat

products of Israel on a Most-Favored-Nation basis. The secondary boycott prohibits individuals, companies

(both private and public sector), and organizations in Arab League members from engaging in business

with U.S. firms and firms from other countries that contribute to Israel’s military or economic development.

Such foreign firms may be placed on a boycott list maintained by the Central Boycott Office (CBO), a

specialized bureau of the Arab League. In the past, the CBO has often provided this list to Arab League

member governments for their use in implementing national boycotts. The tertiary boycott prohibits

business dealings with U.S. and other firms that do business with companies on the boycott list.

Individual Arab League member governments decide whether, or to what extent, to implement boycotts

against Israel through national laws or regulations. Enforcement of such boycotts varies widely among

them. Some Arab League member governments, in particular Syria and Lebanon, have consistently

maintained that only the Arab League as a whole can entirely revoke the boycott it called for. Other member

governments support the view that adherence to a boycott of Israel is a matter of national discretion; thus,

a number of governments have taken steps to dismantle various aspects of their national boycotts. The U.S.

Government has on numerous occasions indicated to Arab League member governments that their officials’

attendance at periodic CBO meetings is not conducive to improving trade and investment ties with the

United States and within the region. Attendance of Arab League member government officials at CBO

meetings varies; a number of governments have responded to U.S. officials that they only send

representatives to CBO meetings in an observer capacity or to push for additional discretion in national

enforcement of the CBO-drafted company boycott list.

The current situation in individual Arab League members is as follows:

ALGERIA: Algeria does not maintain diplomatic, cultural, or direct trade relations with Israel, although

indirect trade reportedly takes place. The country has legislation in place that in general supports the Arab

League boycott, but there are no specific provisions relating to the boycott and government enforcement of

the primary aspect of the boycott is reportedly sporadic. Algeria appears not to enforce any element of the

secondary or tertiary aspects of the boycott. However, regulations issued by individual government

agencies have at times banned contact with Israeli companies and entities, effectively barring the entry of

Israeli products.

COMOROS, DJIBOUTI, AND SOMALIA: None of these countries have taken steps to effectively

enforce a boycott against Israel.

EGYPT: Egypt has not enforced any aspect of the boycott since 1980, pursuant to its peace treaty with

Israel. In past years, Egypt has included boycott language drafted by the Arab League in documentation

related to tenders funded by the Islamic Development Bank.

IRAQ: As a matter of policy, Iraq does not adhere to the Arab League boycott. Most Iraqi ministries and

state-owned enterprises have agreed not to comply with or have rescinded regulations enforcing the boycott,

following a 2009 Council of Ministers decision to cease boycott-related implementation practices.

However, individual Iraqi Government officials and ministries continue to violate that policy. As a result

of U.S. Government engagement with the Iraqi Government, the overall number of boycott-related requests,

FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS | 17

of which the U.S. Government is aware, issued by Iraqi entities declined slightly from 47 in 2019 to 37 in

2020; in 2021, the number rose slightly to 39. The Ministry of Health’s procurement arm (Kimadia) was

among the government entities that still issued boycott-related requests.

Officials from the State Department, Commerce Department, and USTR continue to engage with their

respective interlocutors to ensure Iraqi officials are committed to investigating instances of boycott-related

language in contracts and tenders.

JORDAN: Jordan formally ended its enforcement of any aspect of the boycott when it signed the

Jordanian-Israeli peace treaty in 1994. Jordan signed a trade agreement with Israel in 1995 and later an

expanded trade agreement in 2004. While some elements of Jordanian society continue to oppose

improving political and commercial ties with Israel as a matter of principle, government policy has sought

to enhance bilateral commercial ties.

LEBANON: Since June 1955, Lebanese law has prohibited all individuals, companies, and organizations

from directly or indirectly contracting with Israeli companies and individuals, or buying, selling, or

acquiring in any way products produced in Israel. This prohibition is by all accounts widely adhered to in

Lebanon. Ministry of Economy officials have reaffirmed the importance of the boycott in preventing Israeli

economic penetration of Lebanese markets.

LIBYA: Prior to its 2011 revolution, Libya did not maintain diplomatic relations with Israel and had a law

in place mandating adherence to the Arab League boycott. The Qadhafi regime enforced the boycott and

routinely inserted boycott-related language in contracts with foreign companies and maintained other

restrictions on trade with Israel. The Libyan Government of National Accord has not articulated a stance

on the Arab League boycott, and the status of pre-2011 revolution laws requiring local firms to comply

with the boycott is unclear.

The United States will continue to monitor Libya’s treatment of boycott-related issues.

MAURITANIA: Mauritania does not enforce any aspect of the boycott despite freezing diplomatic

relations with Israel in March 2009 in response to Israeli military engagement in Gaza.

MOROCCO: Morocco agreed to normalize relations with Israel in August 2020. Morocco and Israel

signed a Joint Declaration re-establishing diplomatic relations on December 22, 2020. In January 2021,

Morocco and Israel agreed to establish joint working groups to promote cooperation in a variety of areas,

including investments, transportation, environment, energy, and tourism. Prior to the normalization

agreement, Morocco did not enforce the boycott consistently. Moroccan law contained no specific

references to the Arab League boycott and the government did not enforce any aspect of it. In recent years,

Morocco reportedly has been Israel’s third largest trading partner in the Arab world, after Jordan and Egypt.

U.S. firms have not reported boycott-related obstacles to doing business in Morocco. Moroccan officials

do not appear to attend CBO meetings.

PALESTINIAN AUTHORITY: All foreign trade involving Palestinian producers and importers must be

managed through Israeli authorities. The Palestinian Authority agreed not to enforce the boycott in a 1995

letter to the U.S. Government, and the Palestinian Authority has adhered to this commitment. Various

groups in different countries that advocate for Palestinian interests continue to call for boycotts and other

actions aimed at restricting trade in goods produced in Israeli West Bank settlements.

SUDAN: Sudan and Israel announced a normalization agreement in October 2020 that would include

Sudan renouncing the boycott. In 2021, Sudan repealed the boycott, publishing the repeal in the Sudan

Registry. This move ends Sudan’s official adherence to the boycott.

18 | FOREIGN TRADE BARRIERS

SYRIA: Traditionally, Syria was diligent in implementing laws to enforce the Arab League boycott. The

country maintained its own boycott-related list of firms, separate from the CBO list. Syria’s boycott

practices have not had a substantive impact on U.S. businesses due to U.S. economic sanctions imposed on

the country since 2004. The ongoing and serious political unrest within the country since 2011 has further

reduced U.S. commercial interaction with Syria.

TUNISIA: Upon the establishment of limited diplomatic relations with Israel, Tunisia terminated its

observance of the Arab League boycott. Since the 2011 Tunisian revolution, there has been no indication

that Tunisian Government policy has changed with respect to the boycott.

YEMEN: Although Yemen renounced observance of the secondary and tertiary aspects of the boycott in

1995, in the years since, Yemen has continued to enforce the primary boycott and certain aspects of the

secondary and tertiary boycotts. Ongoing political turmoil in the country has made it impossible to ascertain

current official Yemeni attitudes toward the boycott.

GULF COOPERATION COUNCIL: In September 1994, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) member

countries (Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, and the United Arab Emirates) announced that

they would no longer adhere to what they consider to be the secondary and tertiary aspects of the boycott,

eliminating a significant trade barrier to U.S. firms. In December 1996, the GCC countries recognized the

total dismantling of the boycott as a necessary step to advance peace and promote regional cooperation in

the Middle East and North Africa. Despite this commitment to dismantle the boycott, commercial

documentation containing boycott-related language continues on occasion to surface in certain GCC

member countries and to impact business transactions.

The situation in individual GCC member countries is as follows: