NBER WORKING PAPER SERIES

INTERMEDIARIES IN INTERNATIONAL TRADE:

DIRECT VERSUS INDIRECT MODES OF EXPORT

Andrew B. Bernard

Marco Grazzi

Chiara Tomasi

Working Paper 17711

http://www.nber.org/papers/w17711

NATIONAL BUREAU OF ECONOMIC RESEARCH

1050 Massachusetts Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

December 2011

The present work has been possible thanks to a research agreement between the Italian Statistical Office

(ISTAT) and the Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna. Grazzi and Tomasi gratefully acknowledge financial

support from the European Commission 6th FP (Contract CIT3-CT-2005-513396), Project: DIME

- Dynamics of Institutions and Markets in Europe. Tomasi gratefully acknowledges financial support

by the Marie Curie Program Grant COFUND Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Bernard acknowledges

support from the European University Institute and the Tuck School of Business. The views expressed

herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Bureau of Economic

Research.

NBER working papers are circulated for discussion and comment purposes. They have not been peer-

reviewed or been subject to the review by the NBER Board of Directors that accompanies official

NBER publications.

© 2011 by Andrew B. Bernard, Marco Grazzi, and Chiara Tomasi. All rights reserved. Short sections

of text, not to exceed two paragraphs, may be quoted without explicit permission provided that full

credit, including © notice, is given to the source.

Intermediaries in International Trade: Direct versus indirect modes of export

Andrew B. Bernard, Marco Grazzi, and Chiara Tomasi

NBER Working Paper No. 17711

December 2011

JEL No. D22,F12,F14,L22,L23

ABSTRACT

This paper examines the factors that give rise to intermediaries in exporting and explores the implications

for trade volumes. Export intermediaries such as wholesalers serve different markets and export different

products than manufacturing exporters. In particular, high market-specific fixed costs of exporting,

the (lack of) quality of the general contracting environment and product-specific factors play important

roles in explaining the existence of export intermediaries. These underlying differences between direct

and intermediary exporters have important consequences for trade flows. The ability of export intermediaries

to overcome country and product fixed costs means that they can more easily respond along the extensive

margin to external shocks. Intermediaries and direct exporters respond differently to exchange rate

fluctuations both in terms of the total value of shipments and the number of products exported as well

as in terms of prices and quantities. Aggregate exports to destinations with high shares of indirect

exports are much less responsive to changes in the real exchange rate than are exports to countries

served primarily by direct exporters.

Andrew B. Bernard

Tuck School of Business at Dartmouth

100 Tuck Hall

Hanover, NH 03755

and NBER

Marco Grazzi

LEM Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna

Piazza Martiri della Liberta', 33

56127 Pisa, Italy

Chiara Tomasi

University of Trento

Via Inama, 5

38122 Trento, Italy

and LEM Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna

Intermediaries in International Trade

1 Introduction

The growing availability of firm-level international trade data has contributed to th e blooming

of both theoretical and empirical literatures highlighting the importance of firm heterogeneity

in aggregate trade flows. Since the initial empirical papers of Bernard and Jensen (1995, 1999),

Roberts and Tybout (1997) and the theoretical models of Melitz (2003) and Bernard et al. (2003),

a major f ocus in international trade has been on the relationship between the characteristics of pro-

ducing firms, most notably productivity, and their participation in international trade. An emerging

stream of research has examined differences among trading firms (Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott;

2010b; Ahn et al.; 2011; Antr`as and C ostinot ; 2011). These papers emphasize that exporters in-

clude both manufacturing firms that organize the production and distribution of their goods abroad

as well as intermediaries that specialize in distribution in foreign markets.

In this paper, we examine the underlying factors that give rise to exports by intermediaries

and the consequences in terms of trade volumes and the margins of adjustment to external shocks.

Existing theoretical and empirical work on intermediaries in exporting emphasizes the importance

of country-sp ecific fi x ed export costs and the variation of intermediary export shares across desti-

nations. We extend that focus to include both broader country-level fi x ed costs as well as charac-

teristics of the produ cts themselves.

More importantly, this paper also considers additional implications of the lower fixed costs for

wholesale exporters. If export intermediaries do indeed face lower fixed costs of exporting then

they should also more easily enter and exit export markets in the face of changing profitability.

Firm-level export volumes shou ld respond differently for wholesale exporters and manufacturing

exporters. Aggregating to the country-level, th is firm-level variation implies differential changes in

exports between destinations served primarily by direct and indirect exporters.

Using Italian firm-level trade data, we investigate the importance of intermediaries (wholesalers)

in exports across destinations and products and examine how they differ from manufacturing firms

that export directly. More than one quarter of all exporters are intermediaries and they account

for over 10 percent of Italian exports. However, there is substantial variation in the importance of

intermediaries across countries and products. New Zealand and China have intermediary export

shares near 9 percent (25th percentile) while Paraguay and Malawi are at the 75th percentile with

shares above 23 percent.

Intermediary exporters differ in a number of dimensions from manufacturing firms that export

directly. They are smaller in terms of exports, sales and especially emp loyment as would be

expected since they are only involved in the cross-border distribution of the products and not the

production. However, wholesale exporters display h igher sales per emp loyee and comparable exports

per employee. On average, intermediary exporters reach fewer countries and ship more products

1

Intermediaries in International Trade

than do direct exporters. One important difference between wholesalers and manufacturers lies in

their tendency to ad d and drop products. Intermediaries add and drop prod ucts at much higher

rates than direct exporters. These firms face lower sunk costs of exporting and thus are able to

adjust their extensive margin more easily.

The existence of intermediaries suggests that they overcome barriers to international trade at a

lower cost than manufacturers for some range of goods and for some countries. We examine the role

of both countr y and product characteristics in the choice of the mode of export and the magnitude

of country-product exports. The finding of previous studies that country-specific fixed export costs

are corr elated with the u se of export intermediaries is confirmed in the Italian data. In addition, the

quality of the general contracting environment is related to the choice of mode of export. Exports

through an intermediary are more likely when the quality of the general contracting environment

of the country is weak. Product characteristics also play a role in determining the choice of export

mode. Lower contract intensity, greater product homogeneity, and higher produ ct-level sunk costs

of exporting are associated with a greater reliance on intermediaries in exporting.

The differences in fixed costs across destinations and products give rise to variation in response

to common external shocks to profitability such as exchange rates. Total exports by wholesalers

are less responsive to exchange rate changes precisely because wholesalers are better able to adjust

along the extensive margin. Given the big difference in the share of intermediated exports across

countries and products, these firm-level results suggest that there are potentially large, predictable

differences in how aggregate exports will respond to changes in the value of th e domestic currency.

We indeed find that the responsiveness of aggregate exports is much greater in destinations served

primarily by direct exporters.

Existing theoretical and empirical work on exporting intermediaries is reviewed in S ection 2.

Section 3 describes the firm and country level data. Section 4 documents differences between direct

exporters and wholesalers. The r ole of country and product fixed costs on the choice of export

mode and export values are examined in Section 5. Section 6 explores the response of exports both

at the firm level and in the aggregate to exchange rates shocks. Section 7 concludes.

2 Theoretical frameworks

Recent models of international trade emphasize the role that heterogeneity in productivity plays in

explaining the s tructure of international commerce. According to these models an d a large q uan-

tity of associated empirical work, more productive firms are more likely to engage in exporting and

foreign direct investment. While these frameworks have been extended to examine multiple desti-

nations and multiple products, they generally assume that trade occurs directly between producers

in one country and final consumers in another and do not account for the activity of intermediary

firms in trade.

2

Intermediaries in International Trade

Early theoretical work on the role of intermediaries in international trade, e.g Rauch and Watson

(2004) and more recently Petropoulou (2007), models international trade as an outcome of search

and networks. Several new papers in the theoretical literature on intermediaries in exporting have

taken a more technological pers pective based on models of heterogeneous firms (Ahn et al.; 2011;

Akerman; 2010; Felb er mayr and Jung; 2011).

New models of trade, in particular Akerman (2010) and Ahn et al. (2011), extend the heteroge-

neous firm tr ad e model of Melitz (2003) by introducing an intermediation technology which allows

wholesalers to exploit economies of scope in exporting. While all active firm s serve the domestic

market, manufacturers have a choice of how to potentially serve a foreign market. Domestic man-

ufacturing firms are allowed to choose between direct exports to a consumer in the foreign market

and the use of an intermediary firm who controls the goods as they cross the international border.

1

While the details of the models vary, the general framework is similar. Exporting directly incur s

a fixed cost and a variable cost. Indirect exporting takes place thr ou gh an intermediary firm, or

using intermediary ‘techn ology’. The intermediary is assumed to be able to lower the fixed costs of

exporting while possibly incurring additional variable costs. This choice means that a number of

manufacturing firms may export indirectly through a wholesaler, rather than managing their own

distribution networks. These firms pay an intermediary fixed cost which is smaller than their own

fixed cost of direct export. In this more realistic setting, firms choose to serve the foreign market

either directly or through domestically-based export intermediaries.

Firms sort according to produ ctivity into different export channels. As in the standard model of

Melitz (2003), the least productive firms ser ve only the domestic market while the most p roductive

firms can export directly by incurring the fixed cost of export and any variable trade costs. A

third category of firms chooses to export indirectly through wholesalers. This third group, which

looks like non-exporters in the data, includes some firms who would not have been exporters in

the absence of intermediaries an d some firms who would be marginal exporters in the absence of

intermediaries.

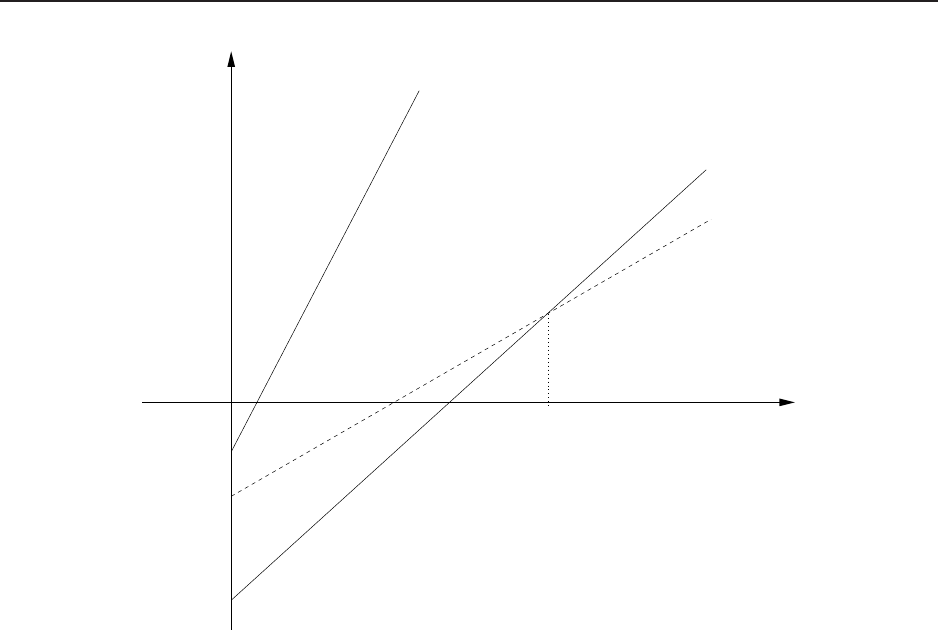

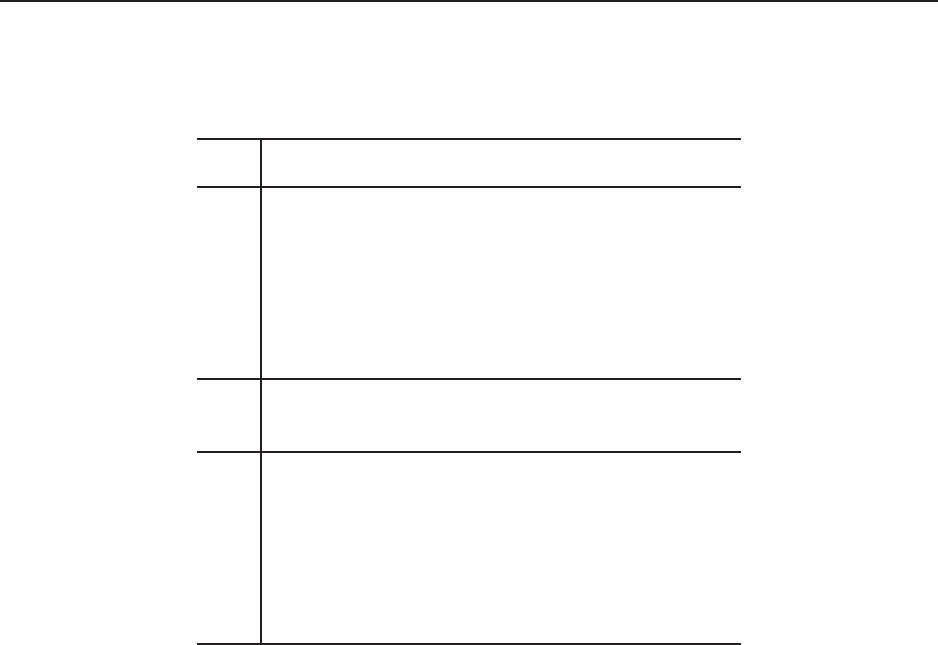

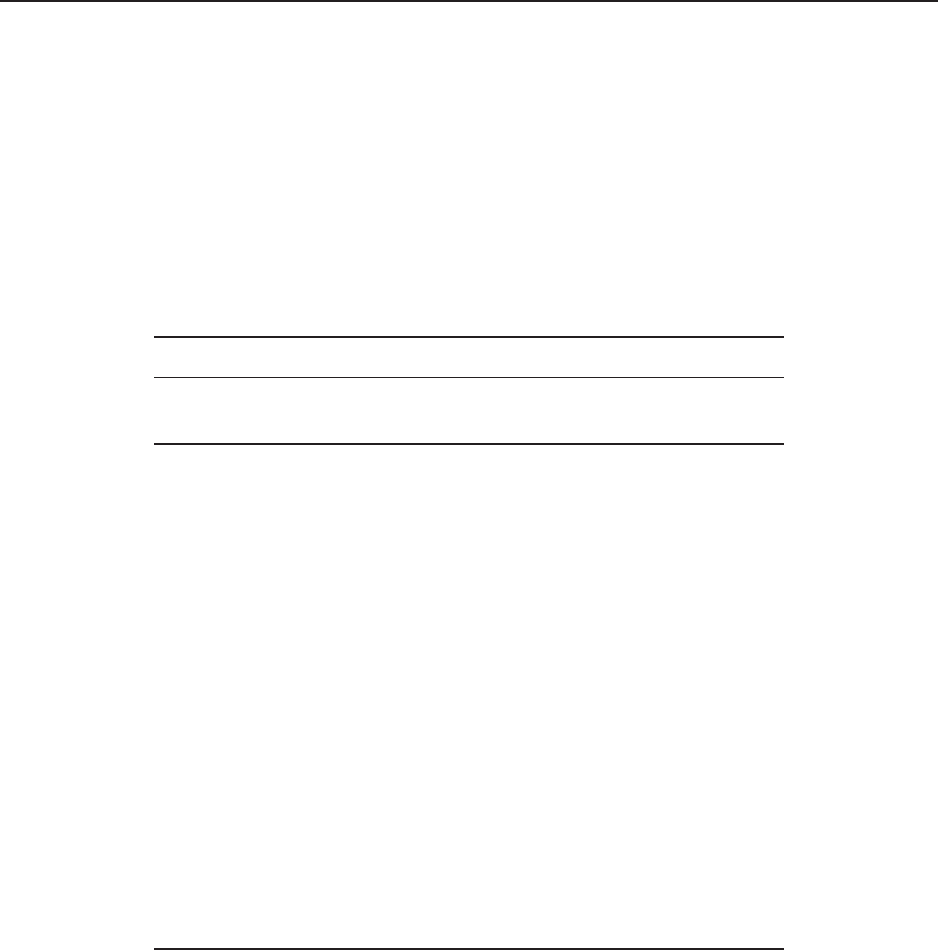

Analogous to Helpman et al. (2004), we can compare graphically the profits generated by each

type of activity for firms with different productivity.

2

The two solid lines in Figure 1 depict profits

from the domestic market (π

d

) and additional profits f or fi rms that export d irectly (π

xd

). The

profit functions are increasing in productivity (α) as more productive firms are able to charge a

1

Blum et al. (2011) and Blum et al. (2010) look the role of intermediaries largely from the perspective of the

imp orting country while Rauch and Watson (2004) discuss when intermediary firms actually take possession of the

goods.

2

In this example we assume that the firm itself has access to the intermediation technology. Akerman (2010)

mod els intermediaries explicitly in a monopolistic competition setting. Intermediaries face fixed costs of exporting

that are increasing in the number of varieties handled by the exporter and their variable costs per variety include

tariffs and the domestic price of the variety. Producing firms view intermediaries as identical to any other domestic

consumer and thus only face domestic fixed costs of production. The resulting pictures an d cutoffs are similar

although his framework allows for a richer set of predictions on the size and scope of intermediaries.

3

Intermediaries in International Trade

α

αα

d

xd

α

xdxi

α

d

π

i

f

d

f

i

f

x

π

π

π

Figure 1: Profits from domestic sales, indirect and direct exports

lower price, capture a large market share and generate larger profits. The intercept of the domestic

curve is smaller in absolute value than that of exports because the fixed costs that are incurred for

selling on the domestic market (f

d

) are lower than what a fir m must pay to export directly abroad

(f

x

). Moreover, since there is a per unit variable cost of export, the slope of the profit function

for direct exports is flatter than the slope of the profit function for domestic production. These

relationships introduce two productivity cut-offs (α

d

and α

x

), that in turn indicate which ranges

of productivity determine exit, domestic sales only, or dir ect exports.

With the possibility of exporting through intermediaries, firms now have also an additional

option of using the intermediation ‘technology’ to export. By assumption the fix ed costs in the

intermediation technology are lower than the fixed costs of direct exporting and are greater than or

equal to the fixed costs of domestic sales; f

i

is between f

d

and f

x

in Figure 1. Th e degree to which

the intermediation fixed costs are lower than those of direct exporting depends on the combination

of country, industr y and country-variety fixed costs of selling in the foreign market as discussed

further below.

The dotted curve drawn in Figure 1 depicts profits for firms that export indirectly (π

i

) through

an intermediary. If using an intermediary does not raise the variable costs of exporting then all

manufacturers would employ the intermediation technology and export indirectly, π

i

(α) > π

d

(α)

4

Intermediaries in International Trade

∀α. To allow for both direct and indirect exporting, the intermediary exporter faces additional

variable costs. In Akerman (2010), the intermediary sets the export price of each variety as a

standard mark-up over its own marginal cost, where its marginal cost includes both variable trade

costs an d the domestic p urchase price of the variety, which is itself a mark-up over the variable

cost of production. In Ahn et al. (2011), it is assumed that intermediaries face no fixed costs of

exporting but charge a variable cost to transport the good s.

The combination of lower fixed costs an d higher variable costs at intermediaries introduces a

third productivity cut-off, α

i

, which is the zero-profit cutoff for exporting through an intermediary.

3

If α

d

< α

i

< α

x

then there will be an equilibrium with ‘pure’ domestic producers and both direct

and indirect exporting. Firms with productivity levels below α

d

earn negative profits and exit the

industry. Firms with productivity levels between α

d

and α

i

, produce only for the d omestic market.

Firms with productivity between α

i

and α

xd

now can profitably access the foreign market thr ou gh

wholesalers. Finally, firms with productivity levels above α

xd

produce for th e domestic market

and export directly. Note that the group of firms with indirect exports includes some firms with

productivity too low to find it profitable to export directly, α

i

≤ α < α

x

and some firm s of higher

productivity that prefer indir ect to direct exporting, α

x

≤ α < α

xd

.

A firm’s decision regarding the mode of export is determined by variable and fixed trade costs,

which in turn also depends on country and product characteristics. The degree to which fixed costs

are reduced using intermediaries depends on the nature of the fix ed cost, e.g. the combination of

country, industry and country-variety components. We can write the fixed costs of direct exporting

of variety k in industry j to country c as

f

x

= f

c

+ f

j

+ f

kc

where f

c

is a fixed export cost common to all varieties exported to country c, f

j

is a fixed export

cost common to all varieties in industry j regardless of the number of destinations, and f

kc

is a fixed

export cost s pecific to the variety and country. The greater the share of idiosyncratic fix ed costs,

f

kc

, in total fixed costs, f

x

, the lower the possibility for economies of scope and the lower the share

of exports handled by intermediaries. Both country and industry-specific fixed costs allow for the

possibility of indirect exporting. Ex porting intermediaries may arise because they are able to share

the country-specific fixed cost of exporting across many industr ies and varieties and/or they may

exist because they are able to spread industr y -specific fixed costs across varieties and destinations.

Existing theoretical frameworks typically ignore the possibility of industry-specific fixed costs but it

remains an empir ical question as to whether intermediaries are country- or industry-specific relative

to direct exporters.

3

It is possible that no produ cer will choose to export through an intermediary if the increase in variable cost is

sufficiently large.

5

Intermediaries in International Trade

The simple framework provides some clear predictions for th e variation of direct and indirect

trade across countries. To the extent that intermediaries solve only the country-specific fixed costs

of exporting, e.g. each variety exported faces indirect fixed costs f

i

= f

c

/n + f

kc

, where n is the

number of varieties handled by the intermediary, the difference between direct an d indirect fixed

costs will be increasing as country fixed costs rise.

The role of variable trade costs is less clear-cut in these models. A rise in variable trade costs that

affects both direct and intermediary exporters, such as tariffs or tran sportation costs, can increase,

decrease or leave un changed the share of exports handled by intermediaries. In the empirical work

we examine the role of variable trade costs including distance and tariffs in determining the share

of exports handled by intermediaries.

The existing theoretical frameworks emphasize the interaction of producer firm heterogene-

ity and fix ed export costs in th e decision to export directly or indirectly. While these models

are all static models of single-prod uct fir ms, it is relatively easy to envision a dynamic exten-

sion where firms potentially make multiple p roducts and their profitability evolves over time (see

Bernard, Redding and Schott; 2010; Bernard et al.; 2011). In a dynamic environment, variation in

the sunk cost of exporting across firm types would lead to predictable variation in product adding

and product dropping in the export market. Firms facing lower s unk costs would be more likely

to both add and drop products in steady state and in the face of exogenous shocks to profitability.

As intermediary exporters have lower entry costs they should be more likely to churn their export

product mix.

2.1 Related empirical literature

Recent papers by Ahn et al. (2011), Akerman (2010) and Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott

(2010b) examine various aspects of intermediaries in exports for China, Sweden and the US, re-

spectively. None of the papers uses exactly the same defi nition of an exporting intermediary so the

results are not directly comparable to each other or those presented below.

4

Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott (2010b) docu ment the role of intermediaries in US ex-

ports. They find th at 35 percent of US exporters are wholesalers accounting for 10 percent of

US exports by value. Their work emphasizes the differences in the attributes between exporters

of different types. Among exporting firms, pure wholesalers are much smaller than ‘producer-

consumer’ firms in terms of employment, but only slightly smaller in terms of exports per worker

4

Specifically, Ahn et al. (2011) define an intermediary as a firm with certain Chinese characters in its

name, Akerman (2010) uses the main activity of the firm and includes both wholesalers and retailers and

Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott (2010b) distinguish between pure wholesalers, pure retailers and two types

of firms that mix manufacturing with wholesaling and retailing. As discussed below we only consider firms with

wholesaling as their main activity as intermediaries.

6

Intermediaries in International Trade

and domestic sales per worker.

5

Other differences include the types of products exported and the

destinations served, wholesalers are more likely to export food-related sectors and export to lower

income countries.

Akerman (2010) reports slightly more exporting intermediaries than manufacturers and signif-

icant differences between the two types of exporters. Intermediaries are sm aller in terms of total

turnover, much smaller in terms of export value, but export more products and ship to more desti-

nations. Akerman (2010) regresses country-sector intermediary export sh ares on gravity variables

and proxies for country fixed export costs. Intermediary export shares increase in distance and

measures of fixed costs and fall with destination GDP.

In contrast with the other studies, Ahn et al. (2011) find much higher exports per fir m and

unit values for intermediaries than for direct exporters. Interm ediaries are also active in m any

more products than direct exporters. Regressions of p roduct-country intermediary export shares

on country characteristics s how positive relationships for distance, tariffs and a measure of fixed

costs and a negative r elationship with destination GDP.

This paper builds on this growing empirical literature and extends it in a number of directions.

First, it documents the differences between produ cing exporters and intermediary exporters in

terms of their firm characteristics, destination and product m ixes, product churning and export

values and quantities. We then examine export participation and levels by direct and intermediary

exporters across countries and products and their relation to country and product characteristics.

Finally the underlying s ou rces of intermediated trade are shown to cause intermediaries to differ

in terms of their responses to aggregate shocks, both in terms of export value and th e margins of

adjustment.

3 Data

3.1 Trade and Firm data

The analysis of dir ect versus indirect modes of export is based upon two firm-level datasets collected

by the Italian statistical office (ISTAT), namely S tatistiche del Commercio Estero (COE) and

Archivio Statistico Imprese Attive (ASIA).

6

The COE dataset consists of all cross-border trans actions performed by Italian firms and it

covers the period 2000-2007. COE includes the annual value and quantity of export tr an sactions

by the firm for product-country destination pairs.

7

A product is defined as a six digit category in

5

‘Producer- consumer’ firms in Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott (2010b) include any firm with no reported

employment in wholesaling or retailing and thus include both manufacturers and other service firms.

6

The database has been made available for work after careful screening to avoid disclosure of individual information.

The data were accessed at the ISTAT facilities in Rome.

7

ISTAT, collects data on exports based on transactions. The European Union sets a common framework of rules

but leaves some flexibility to member states. A detailed description of requirements for data collection on exports in

Italy is provided in the Appendix .

7

Intermediaries in International Trade

the Harmonized System (HS6).

Using the unique identification code of th e firm, we link the firm-level export data to ISTAT’s

archive of active firms, ASIA. In ASIA, firms are classified according to their main activity, as iden-

tified by ISTAT’s standard codes for sectoral classification of business (5-digit ATECO). This infor-

mation allows us to distinguish between four broad categories of firms: manufacturers, wholesalers,

retailers, and a residual group including the remaining sectors.

8

ASIA also contains information on

firms’ operations including the number of employees and total turnover.

9

The combined dataset

used for the analysis is not a sample but rather includes all active firms.

3.2 Country level data

Firm-level trade data are complemented by country characteristics including proxies for market size

and variable and fixed trade costs.

10

For market size we use total GDP from the World Bank World

Development Indicators database. Variable trade costs may be either due to policy barriers, such as

tariffs and non-tariff barriers, or to the cost of moving goods across borders, such as transportation

costs. Following the large gravity literature, transportation costs are proxied by geographic distance

calculated using the great circle formula (Mayer and Zignago; 2005).

As emphasized in the literature on firms and exporting (Roberts and Tybout; 1997; Melitz;

2003; Bernard and Jensen; 2004; Bernard et al.; 2007; Eaton et al.; 2011), firms incur fixed entry

costs in order to enter foreign markets. These fixed costs can be related to the establishment of a

foreign distribution network, difficulties in enforcing contractual agreements, or the uncertainty of

dealing with foreign bureaucracies. We create two measures of country-level fixed costs. To generate

a proxy for the market-specific fixed costs of exporting to a country, we u se information from three

measures from the World Bank Doing Business dataset: number of documents for importing, cost

of importing and time to import (Djankov et al.; 2011). Given the high level of correlation between

these variables, we use the primary factor (Market Costs) derived from pr incipal component analysis

as that factor accounts for most of the variance contained in the original indicators (see Table A1

in Appendix).

Data on the contracting environment are available from a variety of sources, e.g. World Bank,

Heritage Foundation, an d Transparency I nternational. To proxy for institutional quality we use

information from the six variables in the World Bank’s Governance dataset (Kaufman et al.; 2009):

Voice and Accountability, Political Stability and Absence of Violence/Terrorism, Government Ef-

fectiveness, Regulatory Quality, Rule of Law, and Control of Corruption. As these six measures are

highly correlated, we follow Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott (2010a) and use the primary fac-

8

In particular, we classify firms in sectors from 151 to 372 as manufacturers, and firms in sectors from 501 to 519

(with the exclusion of 502 which concerns the activity of repair of motor vehicles) as wholesalers. Retailers are firms

in sectors 521 to 527, and Others contains the remaining sectors.

9

Information on total turnover are available only for two years, 2000 & 2003.

10

More details on the country-level variables are available in the Appendix.

8

Intermediaries in International Trade

tor obtained from principal component analysis, Governance, as the proxy for country governance

quality.

11

If fir ms must invest in fixed resources to export to countries w ith weaker contracting

environments, one would expect better Governance to be associated with lower intermediary export

shares.

Finally, in order to account for the effect of policy barriers on the presence of intermediaries and

manufacturers we also consider HS6 product-country im port tariffs, taken from World Integrated

Trade System (WITS).

12

3.3 Product level data

The paper also investigates a set of product and in dustry variables that affect the probability that

a producer exports directly rather than through an intermediary. Goods with high destination-

specific costs of entering a foreign market, or finding a foreign customer, are more likely to be

exported directly. Similarly in dustries with higher entry costs are less likely to be served by direct

exports.

We consider both produ ct characteristics that are related to the specificity of the product

and those more generally related to market structure. A measure of industry contract intensity

develop ed by Nunn (2007) is used to measure the importance of relationship-specific investment in

intermediate inputs across industries. Nunn’s original data, corr esponding to US I-O in dustries,

is concorded to HS6 products.

13

Industries that require more relationship-specific investments are

expected to be less easily served by intermediaries as the product-market compon ent of fixed costs

is relatively large.

In order to account for differentiation within a HS6 pr oduct class we employ the coefficient

of price dispersion.

14

Lower price dispersion is assumed to be associated with m ore homogeneous

products. For homogeneous pr oducts, the product-market component of fixed costs will be lower

and thus it is more likely that the export transactions will be carried out by an intermediary.

We adapt a measure of product-level sunk entry costs developed by Bernard an d Jensen (2007)

to the export market. In steady state, a produ ct with high sunk costs of entry into export markets

should have a low entry rate and a low (and equal) exit rate. During transitions between steady

states, either the entry rate (expanding product) or the exit rate (shrinking product) may be

11

Table A2 in Appendix reports the results of the principal component analysis for the governance measure.

12

WITS contains the TRAINS database on bilateral tariffs at the six-digit level of the Harmonized System (HS)

product classification for about 5,000 products and 200 countries. TRAINS provides information on four different

type of tariffs: Most-Favored National Tariffs (MFN), Preferential Tariffs (PRF), Bound Tariffs (BND) , and the

effectively applied tariffs (AHS). We use the AHS tariff in the empirical analysis. The AHS tariff is the MFN Applied

tariff, unless a preferential tariff exists.

13

See the Data Appendix for a description of the concordance procedure.

14

The coefficient of p rice variation is computed on COE data as the coefficient of variation in the unit values of any

of the HS6 products across all firm-product-country transactions. In th e empirical analysis we use data from 2003,

but the product ranking in terms of price dispersion does not vary much over the years.

9

Intermediaries in International Trade

unusually high. However, the minimum of the two r ates should still correspond to steady-state

entry or exit. We calculate the m inimum of the firm-level export entry and exit rates for each

product, min(entry, exit).

15

A higher level of entry and exit indicates lower sunk costs of exporting

and a lower likelihood that the prod uct will be exported through an intermediary.

4 Manufacturers and Intermediaries

The focus of the present work is to investigate the role of intermediaries in exports. This section

documents the extent of intermediation in Italian exports, highlighting important stylized facts

about intermediaries and showing how they differ from manufacturing firms. Table 1 reports the

total value of exports and the relative share of four broad categories of firms: manufacturers,

wholesalers, retailers, and a residual group including fi rms in all the remaining sectors.

A prepon derance of exports, more than 84 percent of the value, is perform ed directly by man-

ufacturing firms. Manufacturing exporters also represent more than 50 percent of exportin g firms.

However, an increasing share of exp orts is conducted by the 27 percent of exporters that are whole-

salers, rising from 9.9 percent in 2000 to 11.3 percent of Italian exports in 2007. These figur es

are in line with those reported for the US in Bernard, Jensen, Reddin g and Schott (2010b) wh er e

wholesalers are 35 percent of exporting firms and control just over 10 percent of US exports. As

in other countries, retailers are relatively minor players in exporting, accounting for less than one

percent of exports by value. As a result the paper focuses on the role of wholesalers as export

intermediaries and uses the two terms interch an geably.

While intermediaries account for just 11 percent of Italian exports, there is s ubstantial variation

across both countries and products, see Table 2. At the country level, intermediary export shares

range fr om a low of zero to a high of 88 percent. At the bottom of the interquartile range are

countries such as Belgium, Norway, France, New Z ealand and China with intermediary export

shares close to 9 per cent; at the top of the interquartile range, we find Paraguay, Moldova, Malawi

and Albania with wholesale export shares near 23 percent. While the overall share of intermediary

exports is just u nder 11 percent in 2003, across destinations, unweighted intermediary export shares

average 16.6 percent and are higher on average for non -EU countries. This indicates th at wholesalers

are relatively more important in smaller markets and in markets outside the EU.

The share of intermediaries across prod ucts also displays substantial variation, see the second

panel of Table 2. Wholesalers account for 21 percent of the exports for the average product, pointing

to the importance of intermediaries in p roducts with lower total export values. While there exist

15

The entry rate is the number of new exporters of the product between year t and t+s divided by the average

number of exporters in the two years. The exit rate is the number of firms that stop exporting the product between

t and t+s divided by the average numb er of exporters in the two years. The min(entry, exit) in a given product is

computed on COE data for years 2003 and 2007. Considering different years for the computation of the rates does

not significantly affect the results.

10

Intermediaries in International Trade

both products which are sold ab road only through intermediaries, 1.8 percent of 5,125 products,

and others wh er e the share of wholesalers is zero, most products are exported both directly and

indirectly.

Specialization is more common at the product-country level. Of the 244,614 product-country

combinations with positive exports, 48.6 percent involve direct exports only and 10.4 percent are

served exclusively by intermediaries.

16

4.1 Firm characteristics

In their work on US traders, Bernard, Jensen, Redding and Schott (2010b) find not only that

traders differ from domestic firms, but also that substantial h eterogeneity exists between trad-

ing firms of different ‘types’. The results here complement and extend that analysis by comparing

manufacturers and wholesalers along a number of dimensions including size, the number of desti-

nation countries and the number of products exported.

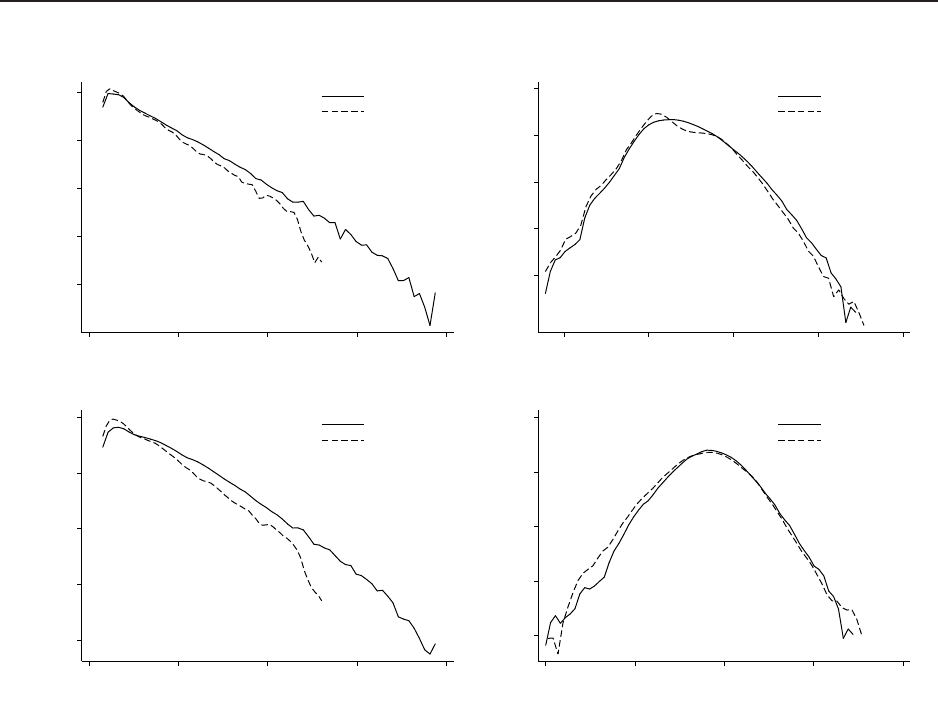

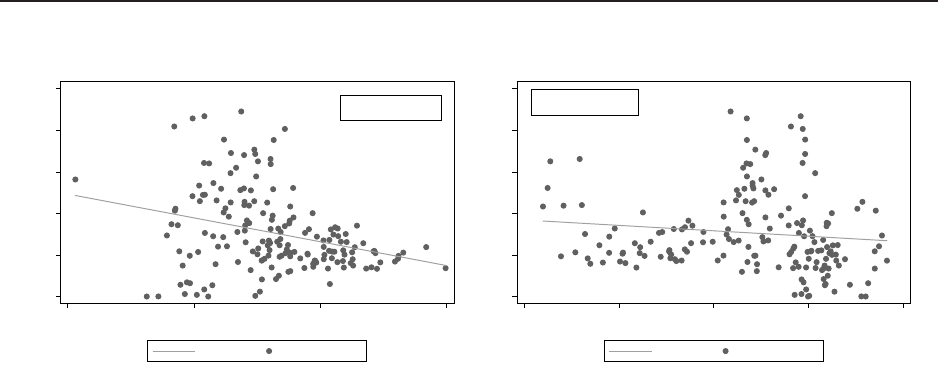

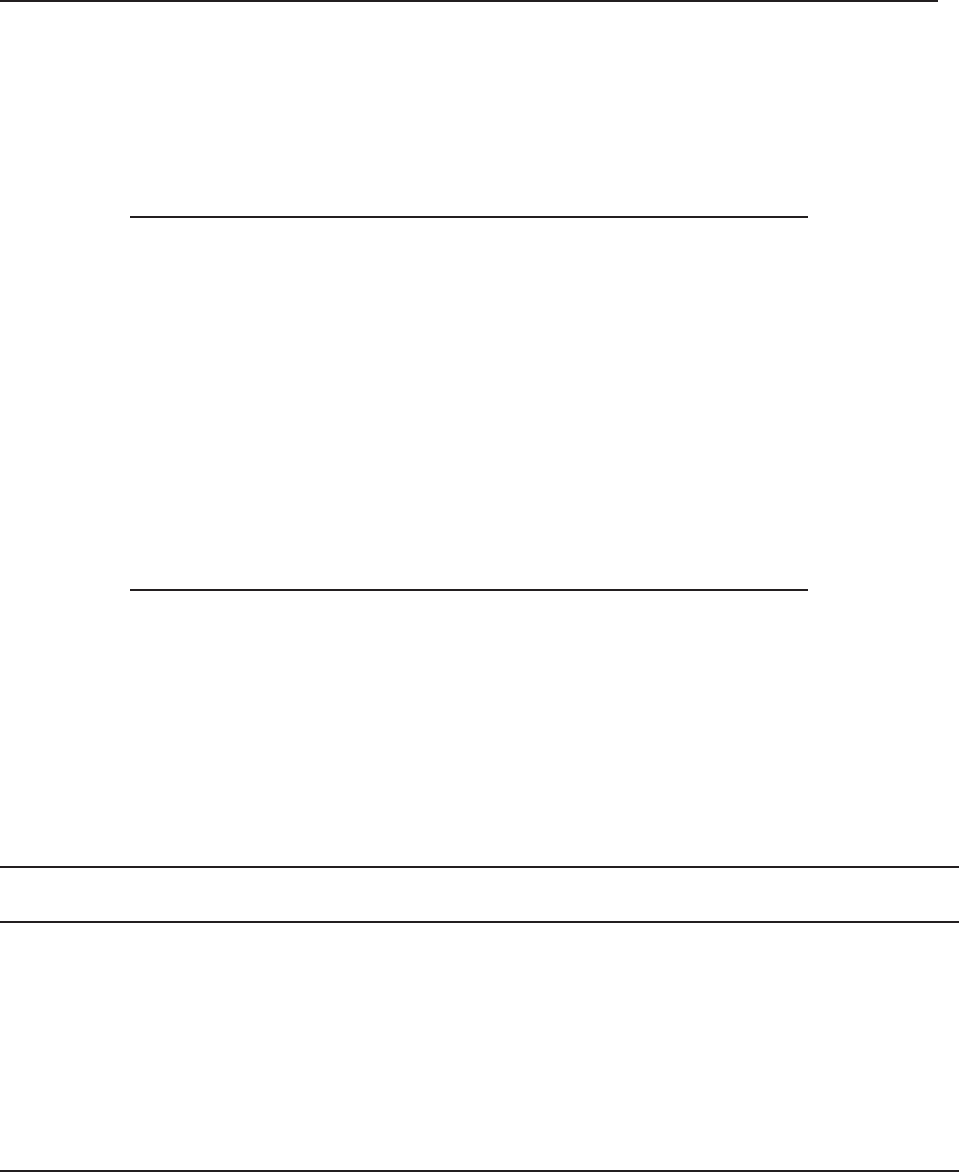

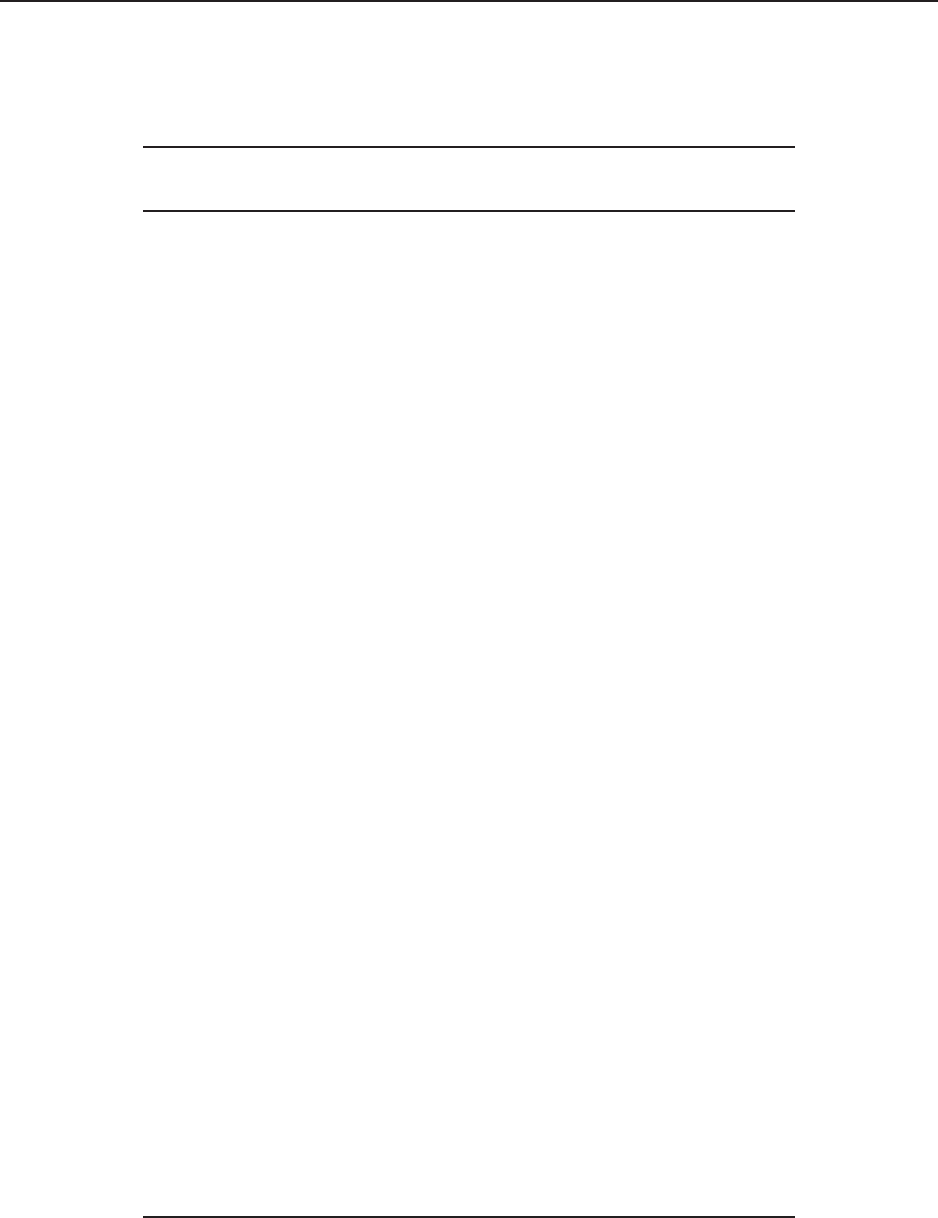

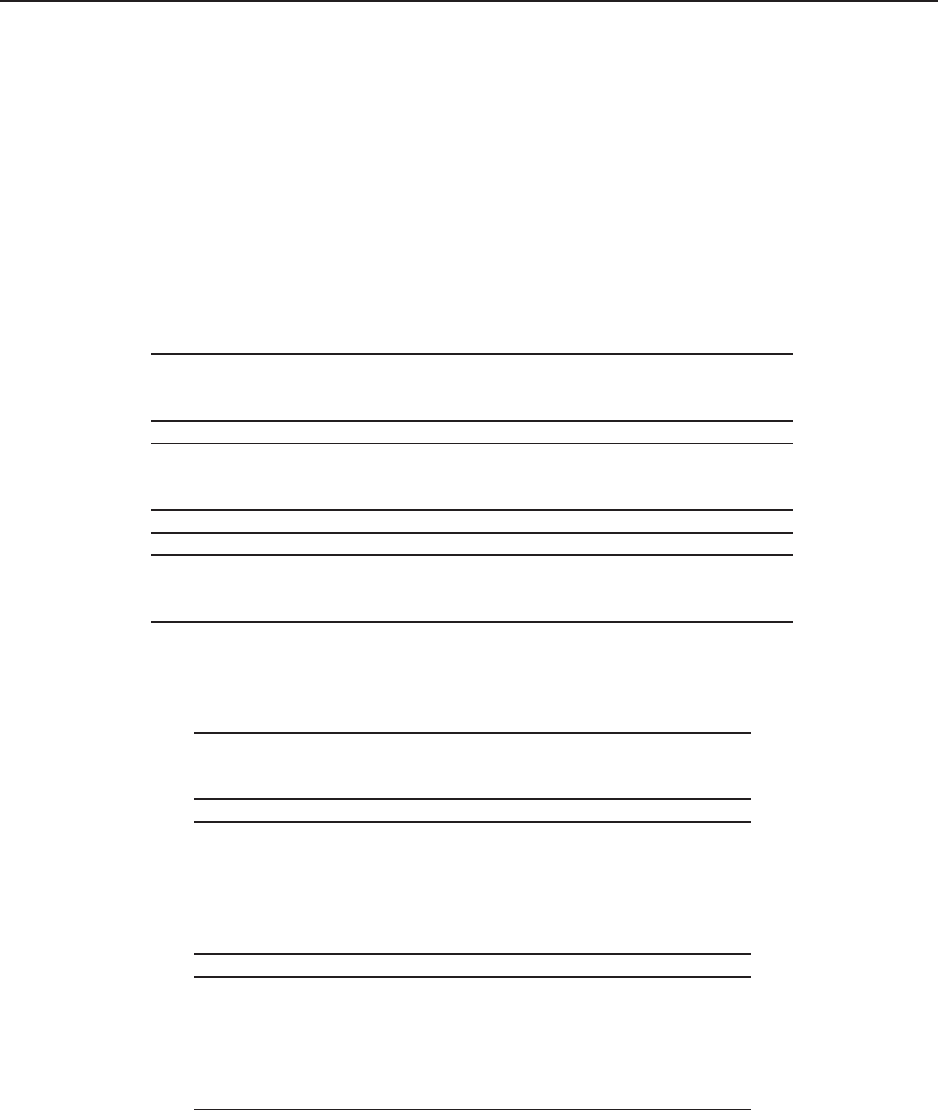

The top left panel of Figure 2 shows the distribution of employment for all wholesale and

manufacturing firms. Th e employment distribution for wholesalers lies far to the left of that for

manufacturers. Overall, intermediaries are much sm aller in terms of number of employees. However,

when we proxy size with total sales (top right panel) the difference between the two distributions

remains but is greatly reduced. The differences between the panels implies that the sales per

employee ratio of wholesalers is much h igher than that of manufacturers.

17

The bottom panels

of Figure 2 show the size distrib utions for wholesale and manufacturing exporters. The relative

ranking of the two distributions is similar to that seen above.

The figures are consistent with the idea that manufacturing firms are performing two activi-

ties, the physical p roduction of the goods and the intermediation of the goods to a downstream

customer, while wholesalers are only engaged in the latter activity. This distinction is important

when attempting to compare the exporting activities of wholesalers and manufacturers as the use

of employment as a proxy for firm size may yield misleading comparisons. A manufacturing firm

with 100 emp loyees will typically have lower sales and exports than a wholesale firm with the same

employment. As a consequence, we use both employment and total sales as proxies for size in the

analysis.

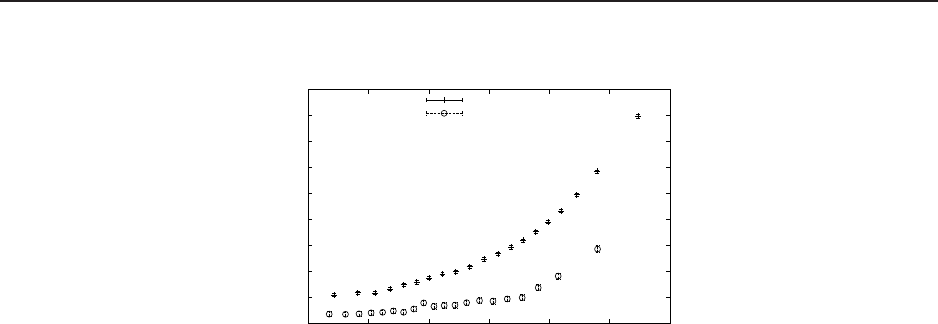

Figure 3 displays the binned relation between log exports and log employm ent, reporting the

(log) number of employees a firm needs, on average, for a certain level of exports.

18

The plot

16

For product-country pairs with a mix of direct and indirect exports the average indirect share is 25.3 percent.

17

We caution that sales per employee is not a good m easure of firm product ivity when comparing firms of d ifferent

types.

18

Binned plots allow for a succinct representation of the relation between two variables and avoid displaying clouds

of thousands of observations. Here data are placed in 20 equally-sized bins according to th eir (log of) export value,

and the x-coordinate d isplays the average of the bin. The y- coordinate is the average (log of) employment within

that bin.

11

Intermediaries in International Trade

.0001

.001

.01

.1

1

Probability Density

2 4 6 8 10

Log(Number of Employees)

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

Size Distribution

.0001

.001

.01

.1

1

Probability Density

5 10 15 20 25

Log(Sales)

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

Size Distribution

.0001

.001

.01

.1

1

Probability Density

2 4 6 8 10

Log(Number of Employees)

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

Size Distribution for Exporting firms

.0001

.001

.01

.1

1

Probability Density

5 10 15 20 25

Log(Sales)

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

Size Distribution for Exporting firms

Figure 2: Empir ical density of fir m size in 2003 - All fi rms (Top) and Exporters (Bottom). S ize is

proxied by (log of) employment (Left) an d (log of) sales (Right). Densities estimates are obtained

using the Epanenchnikov kernel with the b an dwidth set using the optimal routine described in

Silverman (1986).

confirms that wholesalers require fewer employees to attain any given level of export value.

To quantify the differences between manufacturers and wholesalers, we estimate the following

cross-sectional OLS regression,

ln Y

f

= c + δD

W

f

+ βD

X

f

+ γ(D

W

f

· D

X

f

) + ε

f

(1)

where ln Y

f

denotes the logarithm of either total sales, number of employees, or sales per employee

ratio. D

W

f

is a firm-level dummy variable, one f or wholesaler and zero for manufacturer; D

X

f

is

a dummy indicating if a firm is an exporter; and (D

W

f

∗ D

X

f

) is the interaction between the two

dummies and takes value of one if a firm is a wholesaler exporter and zero otherwise. The results

are presented in Table 3.

As expected, manufacturers are on average larger than wholesalers, 0.111 log points (12 per-

cent) in terms of sales an d 0.533 log points (70 percent) in terms of emp loyment, δ is negative and

12

Intermediaries in International Trade

1

1.5

2

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6 8 10 12 14 16 18

ln Employment

ln Exports

Employment per level of exports

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

Figure 3: Relation between (log of) employment and exports, 2003. Observations are placed in 20

equally-sized bin s according to the variable on x-axis. Coordinates of dots display the average of x

and y variables of the data in each b in (see text).

significant in both specifications. In contrast, sales per employee are substantially higher at whole-

salers. We also confirm the now-standard results that manufacturing exporters are dramatically

larger and have higher sales per employee than their domestic counterparts, β is large, positive and

significant.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, we provide the fir st evidence that the selection of firms into exporting

may be working for wholesalers as well. Exportin g wholesale fi rms have total sales 14.8 times

larger than non-exporting wholesalers and employ 2.8 times as many workers, β + γ is positive and

significant. Sales per employee at exportin g intermediaries are 5 times higher than at non-exporters.

Looking at exports in columns 4 and 5 of Table 3, we find that the value of exports at wholesalers

is also much smaller than that of manufacturing exporters but that this difference largely disappears

when considering exports per employee.

The regression results of Table 3 confirm the conclusions from the relative distributional plots in

Figure 2. In particular, the evidence on higher sales per employee, especially at exporters, supports

the idea that wholesalers focus on just the intermediation portion of the activities carried out by

manufacturers.

4.2 Product and Geographic Diversity

The theoretical models discussed in Section 2 generally focus on the role of intermediaries in solv-

ing the fixed cost problem for specific markets. This section prov ides evidence on the presence

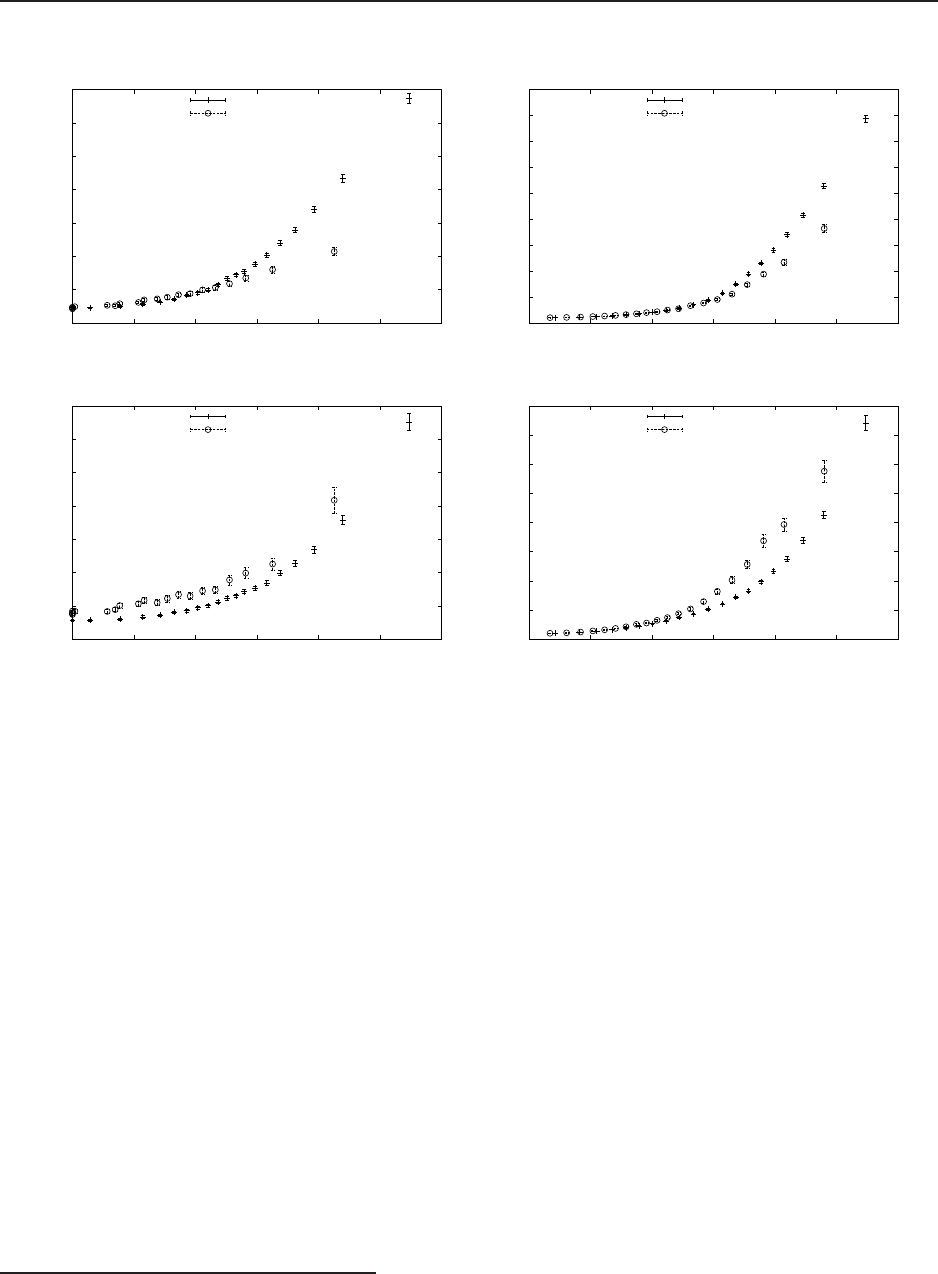

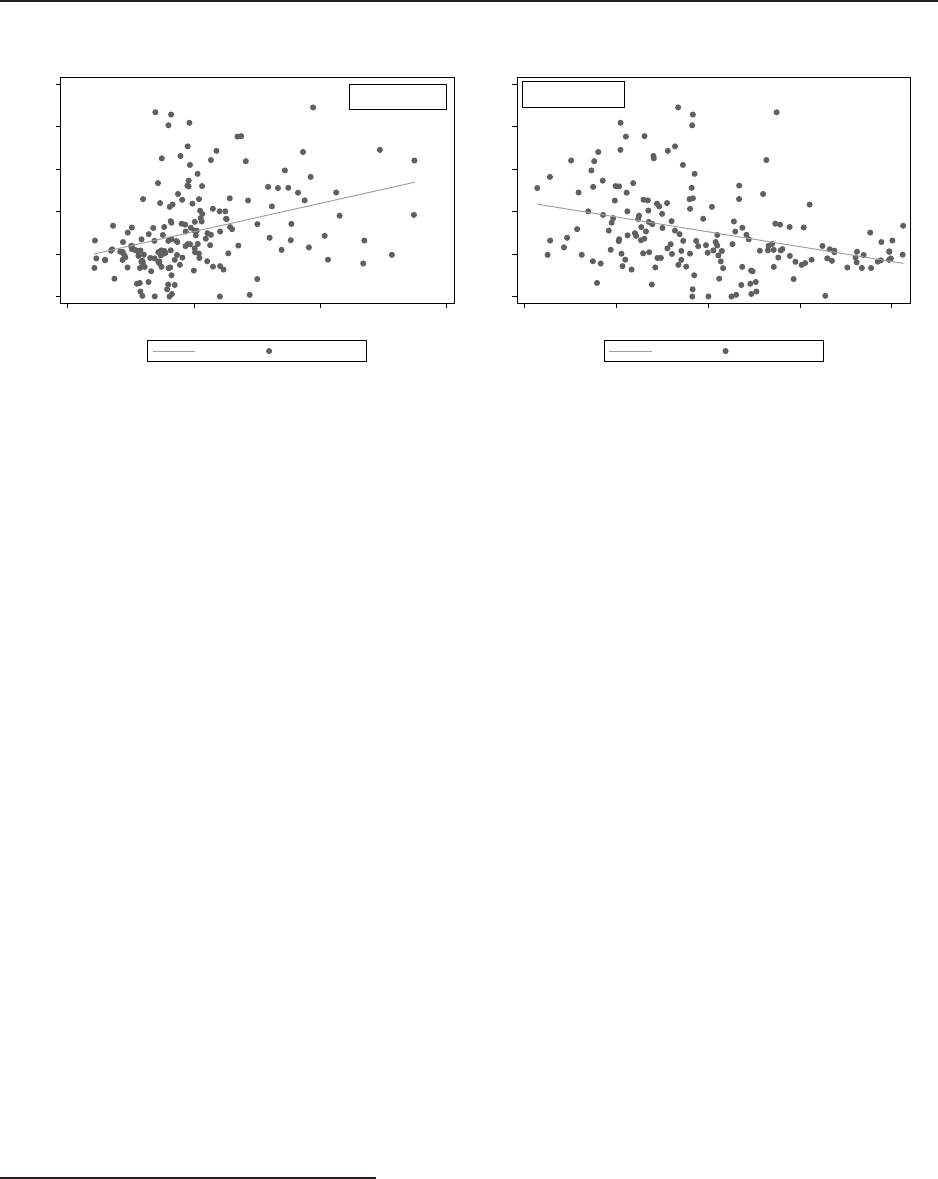

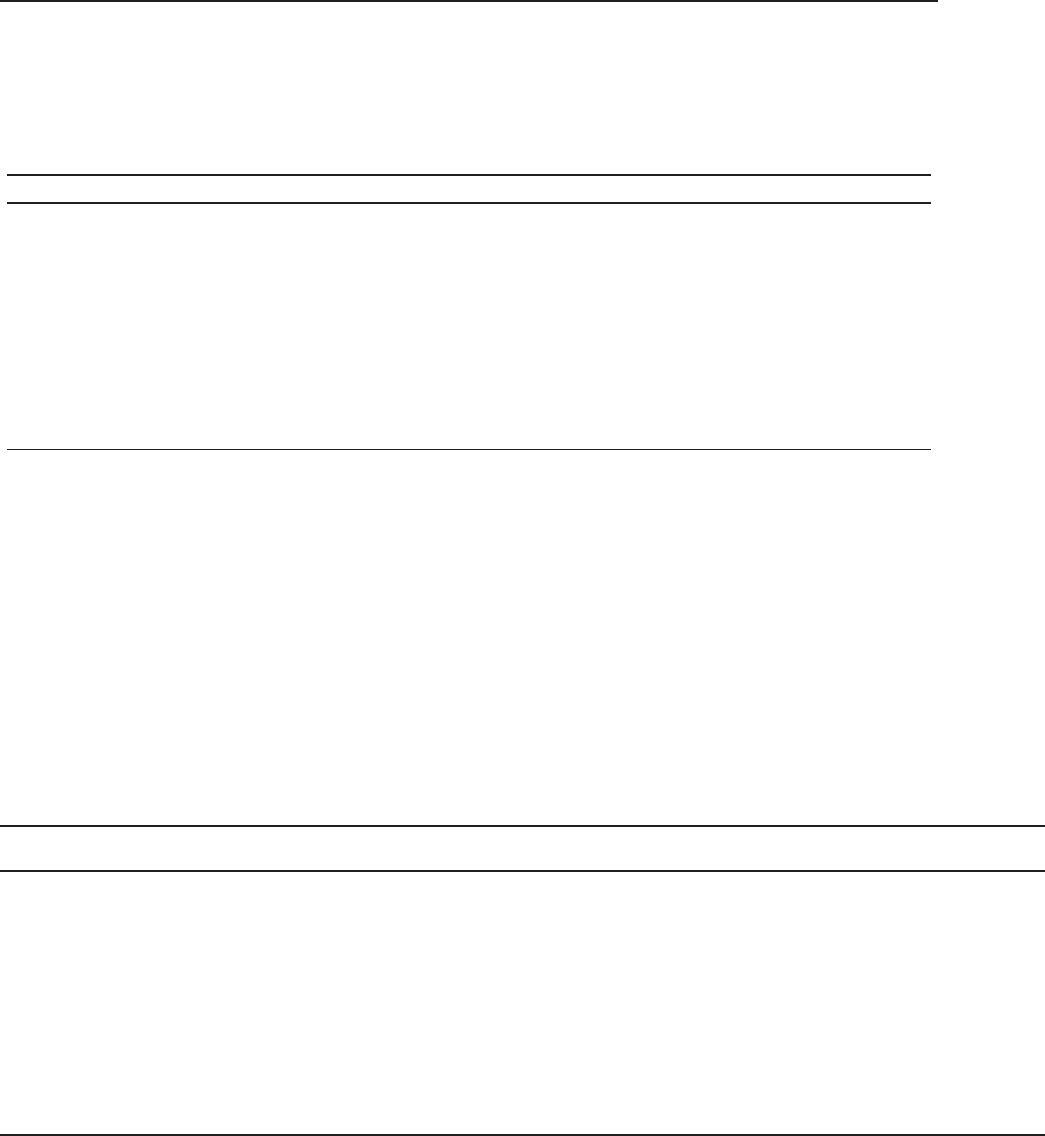

of intermediaries in markets and sectors. Figure 4 displays th e relation between geographic and

product diversification of the firm and its size, distinguishing between wholesalers and manufactur-

ers. Geographic diversification is proxied by the number of destination countries (Countries

f

) and

product diversification by the number of products exported (P roducts

f

); size is represented both

13

Intermediaries in International Trade

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Number of countries

ln Employment

Number of Countries and Employment

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Number of countries

ln Exports

Number of Countries and Exports

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

Number of Products

ln Employment

Number of Products and Employment

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Number of products

ln Exports

Number of Products and Exports

Manufacturers

Wholesalers

Figure 4: Top Number of countries and (left) employment and (right) exports, in 2003. Bottom

Number of products and (left) employm ent and (right) exports, in 2003. Observations are placed

in 20 equally-sized bins according to the variable on x-axis. Coordinates of dots display the average

of x and y variables of the data in each bin (see text).

by employment and export value.

The evidence in Figure 4 suggests that the wholesalers’ technology does not convey them an

advantage in terms of geographic diversification, wholesalers export to fewer countries than do

manufacturers at similar levels of employment and exports.

19

On the contrary, when considering

the relation between firm size and product diversification (bottom panel), we find that, at every

size class, wholesalers export more produ cts than manufacturers.

Table 4 reports the results of the regression of the number of products exported and the number

of destination markets (Products and Countries, respectively) on the firm wholesaler dummy, D

W

f

,

and a proxy f or firm size,

Y

f

= c + δD

W

f

+ ln Size

f

+ ε

f

if D

X

f

= 1. (2)

19

Ahn et al. (2011) report that Chinese intermediaries export more products and export to more countries than

direct exporters. However, as noted previously, Chinese intermediary export firms are almost twice as big as direct

exporters in terms of total export value.

14

Intermediaries in International Trade

The firs t row of Column 1 shows that, unconditionally, wholesale exporters export fewer HS6

products. However, including a control for firm size, either log employment or log export value, the

coefficient becomes positive and significant; exporting intermediaries are active in a wider range of

products compared to similarly-sized manufacturers. In contrast, intermediaries serve fewer export

markets even when adjusting for firm size. These resu lts su ggest that intermediaries are indeed

able to spread country-specific fixed costs over a wider range of products.

4.3 Within Product-Country

The availability of product level data allows the comparison of wholesalers and manufacturing

exporters within product-country destinations.

20

Using exports to Extra-EU d estinations for 2003

and considering product-country pairs where both wholesalers and manufacturers are active, we

estimate the following specification,

ln Y

fcp

= c + δD

W

f

+ β ln Sales + d

pc

+ ε

fcp

(3)

where ln Y

fcp

denotes the logarithm of, respectively, th e total value, quantity and unit value of

the firm’s exports in the country-product pair, D

W

f

is the firm wholesaler dummy and d

pc

denotes

country-product fixed effects. The results in the first two columns of Table 5 show that wholesalers

have a substantially lower total value of exports relative to direct exporters within product-country

pairs. The difference in exports across firm types remains even after controlling for firm size,

although the magnitude is reduced. Columns 3-6 report similar regressions for export qu antities

and unit values. The lower exports for wholesalers are driven entirely by lower export quantities;

unit values are not statistically different for direct and intermediary exporters.

4.4 Product Adding and Dropping

The cross-sectional analysis reveals that exporting wholesalers are smaller than manufacturers and

that they export a larger number of products to a sm aller set of destinations. In addition to lower

firm-level trade flows, intermediaries also ship less within a product-country p air. These results

are broadly supportive of a framework emph asizing country-specific fixed costs of exporting. As

discussed earlier, the presence of s unk export costs that vary across firm types also has implications

for export dynamics. Lower sunk costs should result in higher probabilities of both entry into

exporting and exit from exporting. A dynamic extension of the framework presented earlier would

suggest that intermediaries should be more likely to add and drop products from their export

portfolio than direct exporters. This is confirmed by the unconditional drop rates across firms

20

We focus all the remaining empirical work on exports to Extra-EU destinations for several reasons. Most im-

portantly, firm-level exports to the EU are not recorded for all exporters and these criteria have changed over time.

Also, real exchange rate changes within the eurozone countries are driven entirely by changes in relative price levels.

15

Intermediaries in International Trade

types: on average the fraction of exported firm-produ cts outside the EU that is dropped every year

is 50% among all firms, 48% for manufacturers and 53% for wholesalers.

Following Bernard, R edding and Schott (2010), we analyze export product switching between

t and t + 1 using those years for which we have information on firms’ total turnover, 2000-2001 and

2003-2004. We estimate a linear probability model of product dropp ing for firms that export in

year t and t + 1 of the form,

Drop

fpt

= c + δD

W

ft

+ β

1

ln Sales

ft

+ β

2

Deviation

fpt

+ β

3

ln P roducts

ft

+ d

p

+ d

t

+ ε

fpt

(4)

where Drop

fpt

takes value 1 if the product is exported by the firm f in year t and not exported in

year t +1 an d equal zero if the produ ct is exported in both years. D

W

ft

is the firm wholesale dummy

and is the variable of interest. To control for firm attributes associated with product switching, we

include firm size, ln Sales

ft

, the relative importance of the firm in the exports of the product given

by the log difference between the firm’s exports in product p and average firm exports in product p ,

Deviation

fpt

, and the number of products exported by the firm in year t, ln P roducts

ft

. Product

and year fixed effects, d

p

and d

t

respectively, are also included.

Table 6 reports the results of the estimation of the firm-pr oduct droppin g specification equa-

tion 4 for Extra-EU countries. Wholesaler exporters are much more likely to drop a pr oduct than

manufacturer exporters, 6.9 percentage points or 14.4 percent. This differential persists even con-

trolling for firm size, the number of exported products and the relative importance of the firm in

the product, although the magnitude of the coefficients is reduced.

If wholesalers have lower sunk costs per product, then they s hould also be more likely to add

products.

21

We examine the probability that a current exporter adds a product to its export

portfolio between years t and t + 1 in the specification,

Add

ft

= c + δD

W

ft

+ β

1

ln Sales

ft

+ β

2

ln P roducts

ft

+ d

ind

+ d

t

+ ε

ft

(5)

where Add

ft

takes value 1 if the firm adds an export product and zero otherwise. D

W

ft

, ln Sales

ft

,

and ln P roducts

ft

are defined as above. Add itional controls include year fixed effects, d

t

, and

industry-mix fixed effects, d

ind

that controls f or firm s with the same mix of industries at the HS2

level.

22

Results of Table 7 show that intermediaries are more likely to add a product th an manufacturers.

This finding is robust to controlling for firm size and number of exported products, and the effect

is more pronounced when comparing wholesalers and manufacturers among single product firms.

21

On average the fraction of firms that add at least one export product outside the EU every year is 79%: 79% for

manufacturers and 80% for wholesalers. Among single product (multiple products) firms the ratio is 65% (83%) for

all firms, 62% (83%) for manufacturers and 69% (83%) for wholesalers. On average the fraction of firms that drop

at least one export p roduct outside t he EU every year is 80%: 80% for manufacturers and 79% for wholesalers.

22

While the dropping regression was estimated at the firm-product level, the adding specification is at th e firm-level.

16

Intermediaries in International Trade

b=−0.011 (0.003)

0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5

Intermediary Export Share

15 20 25 30

Log (GDP)

Linear Fit Observed Value

Wholesale Export Share & Market Size

b=−0.0013 (0.008)

0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5

Intermediary Export Share

6 7 8 9 10

Log (Distance)

Linear Fit Observed Value

Wholesale Export Share & Market Distance

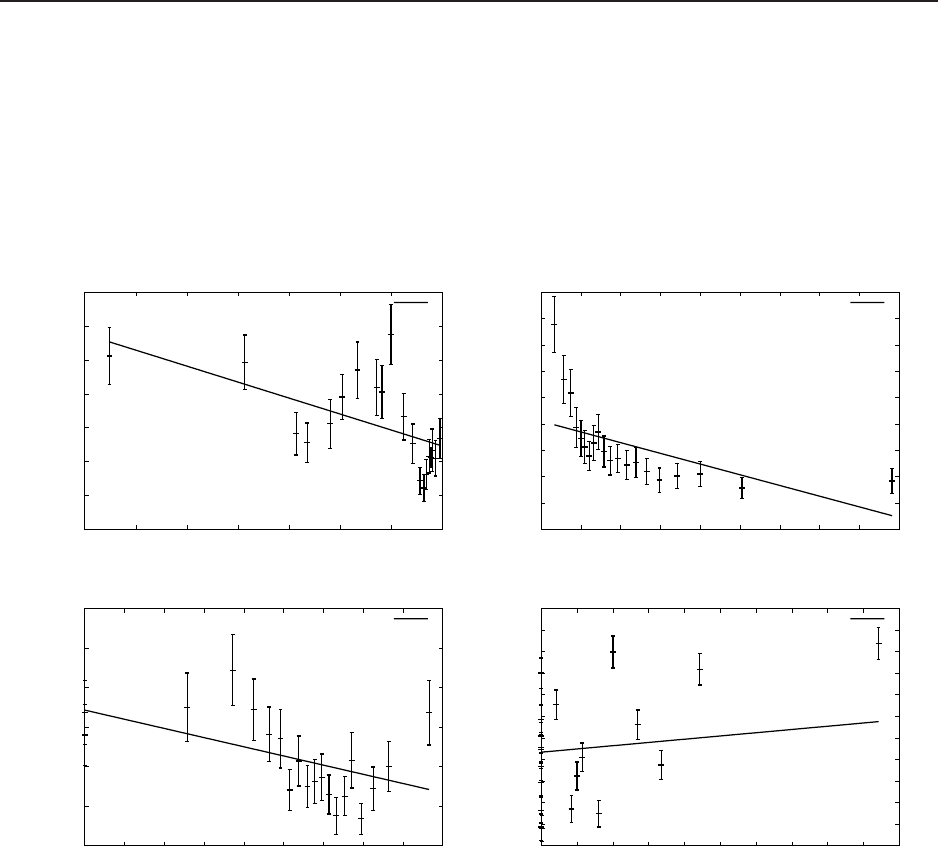

Figure 5: Wholesale export share and gravity variables, 2003. Figures report the relationship be-

tween wholesale export share and gravity variables: (Left) Real GDP; (Right) Geographic distance.

Each panel reports the coefficient, b, of a country-level univariate regression for intermediary export

share. Robust standard error is shown in parenthesis.

The results on both export product dropping and export produ ct adding suggest that interme-

diary exporters face lower sunk costs of participation in the export market. These findings suggest

that shocks such as changes in tariffs or exchange rates may have differential effects on wholesalers

and manufacturers even within the same country-product pair. We return to examine the effects

of exchange rate changes across firm types in the final s ection of the paper.

5 Exports by Intermediaries

The previous sections have shown that exporting wholesalers differ from manufacturing exporters

in terms of size, geographic coverage, product portfolio and entry and exit. This section focuses on

differences in the role of wholesalers across countries and products.

5.1 Intermediary E xport Share

We start by exploring the relationship between the intermediary export sh are by destination market

and a set of relevant country variables (Figures 5-6). The correlation of intermediary export shares

by country with market size and distance is displayed in the two panels of Figure 5. Wh olesale

export share is declining in log GDP, smaller markets have greater intermediary export shares,

consistent with the idea that in s maller destination markets, fixed entry costs have to be spread

over fewer units. In contrast, there is no statistically significant relationship between distance, a

common proxy for variable trade costs, and the intermediary export share.

Country-specific fixed costs of trade are generally expected to be positively related to inter-

17

Intermediaries in International Trade

b=0.033 (0.007)

0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5

Wholesale Export Share

−2 0 2 4

ln (Market Costs)

Linear Fit Observed Value

Wholesale Export Share & Market Costs

b=−0.035 (0.005)

0 .1 .2 .3 .4 .5

Intermediary Export Share

−2 −1 0 1 2

Governance Indicator

Linear Fit Observed Value

Wholesale Export Share & Governance Indicator

Figure 6: Wholesale export share and country-level fixed costs, 2003. Figures report the relationship

between wholesale export share and the two proxies for fixed market entry costs: (Left) Market Size;

(Right) Governance indicator. Each panel reports the coefficient, b, of a country-level univariate

regression for intermediary export share. Robust standard error is shown in parenthesis.

mediary tr ad e shares.

23

The plot at the left of Figure 6 displays the relationship between the

percentage of export value that goes through intermediaries and the Market Costs variable. As

found by Ahn et al. (2011) and Akerman (2010 ), this measure of market access costs is positively

and significantly related to intermediary trade shares.

The right panel of Figure 6 plots the intermediaries export share against country Governance.

As expected, the quality of country governance is negatively and significantly related to intermedi-

aries export share. This evidence supports the idea that as country-level fixed costs increase, more

firms use wholesalers for exporting.

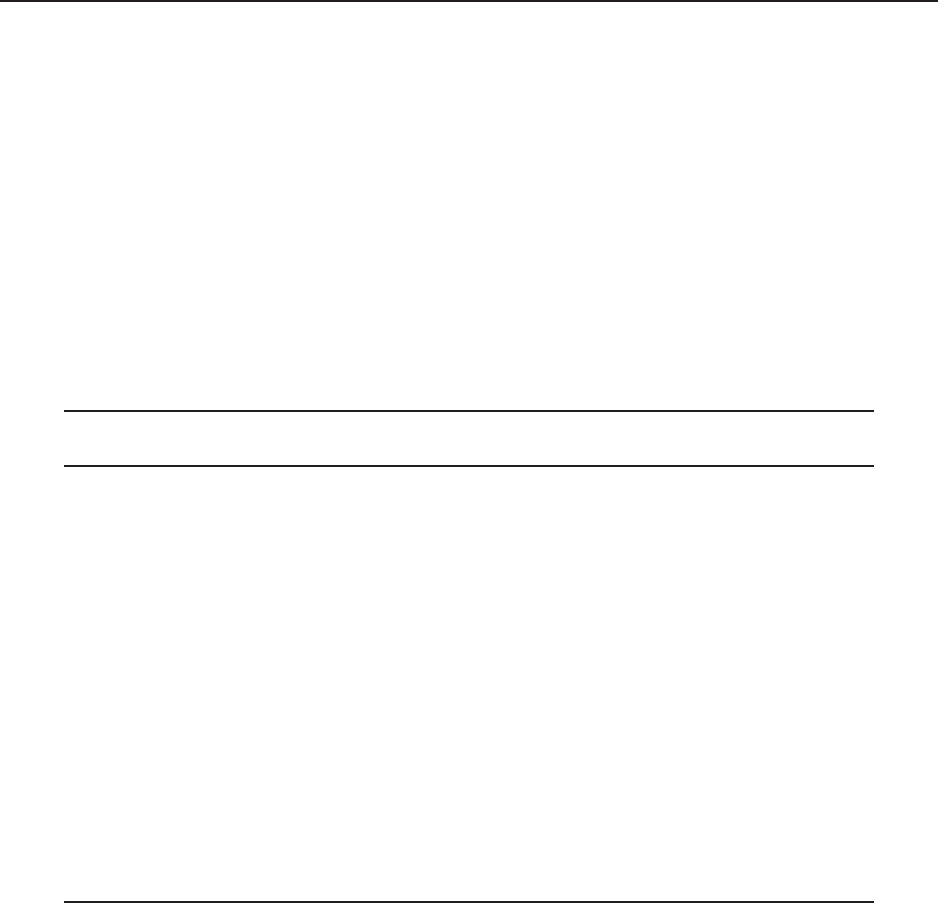

Finally, we investigate the link between the HS6 p roduct characteristics and intermediary export

shares. While the theoretical models remain largely silent on th is aspect, product characteristics

would be expected to play a r ole in explaining the type of fi rm handling the exports.

24

If goods w ith

higher relation-specificity have relatively larger product-country fixed costs of exporting, the share

of direct exports is likely to be greater. Transactions involving complex goods, whose production

process is intensive in the use of highly specialized and customized inputs, may require specific

knowledge and tasks because of the effort associated with the identification of potential customers,

more detailed contracts, post-sale service, etc. For those goods, the product-market component of

fixed costs is relatively large and such goods are more likely to be exported directly by manufacturing

23

Higher country-level fixed costs of exporting and weaker governance are associated with smaller total levels of

exports (Lawless; 2010; Djankov et al.; 2011), here we consider their relationship to the comp osition of exports by

firm type.

24

While not discussed explicitly in his paper, Akerman (2010) models the p rice of exports by intermediaries as

a double mark-up over tariff-adjusted marginal cost. Increases in the d emand elasticity reduce the mark-ups and

narrow the difference between the export p rices of intermediaries and th ose of direct exporters and increase the share

of exports by intermediaries.

18

Intermediaries in International Trade

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

Wholesale Export Share

Relation Specificity

Wholesale Export Share & Relation Specificity

b=-0.236 (0.023)

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.45

0.5

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Wholesale Export Share

Price dispersion

Wholesale Export Share & Coeff. of Variation

b=-0.020 (0.001)

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9

Wholesale Export Share

Entry/Exit rate

Wholesale Export Share & min(entry,exit)

b=-0.116 (0.017)

0.15

0.16

0.17

0.18

0.19

0.2

0.21

0.22

0.23

0.24

0.25

0.26

0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50

Wholesale Export Share

Tariff

Wholesale Export Share & (all product-country) tariffs

b=0.0003 (2.959e-05)

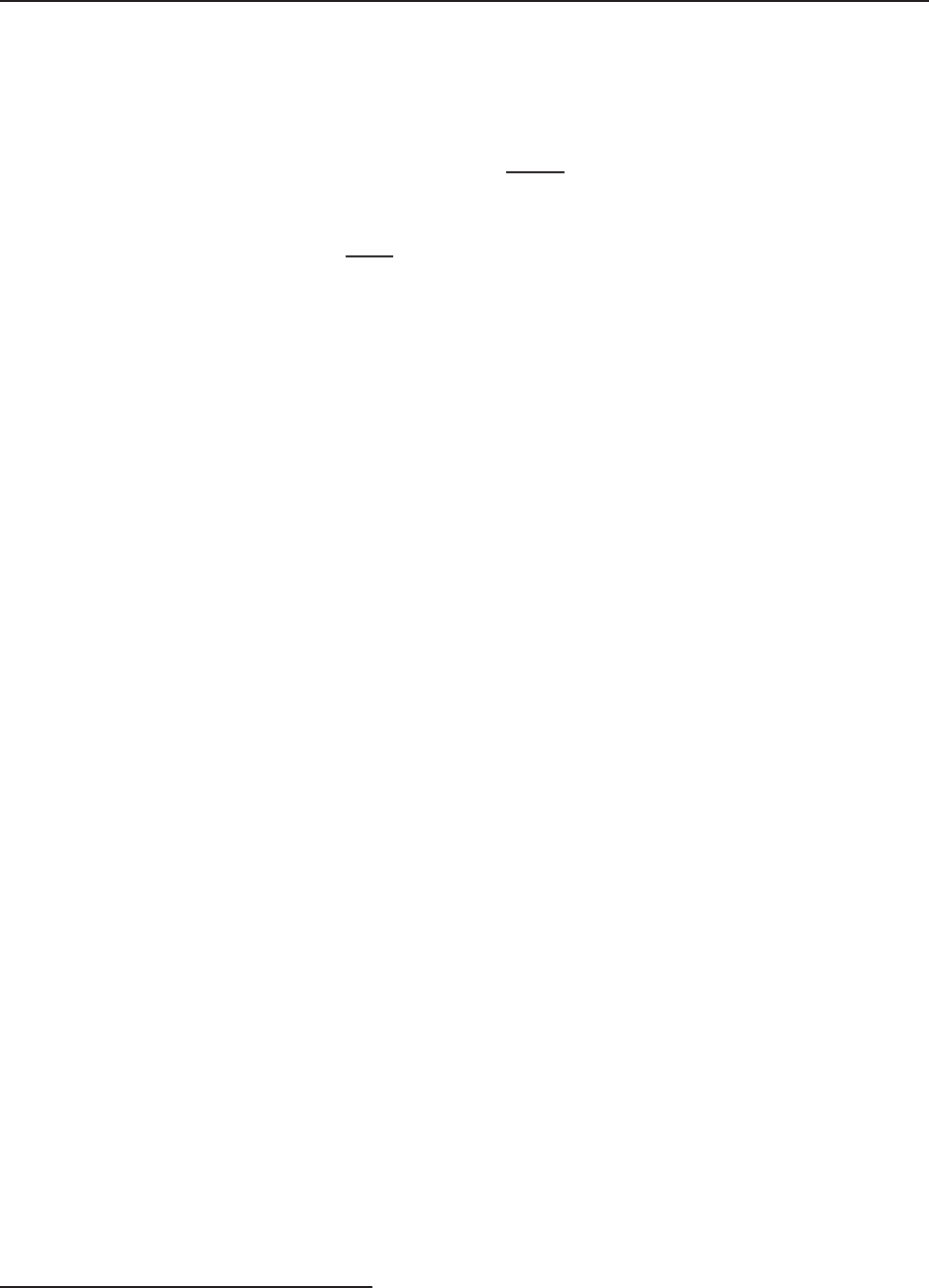

Figure 7: Wholesale export share an d Product/Country-Product characteristics, 2003. Figures

display the relationship between wholesale export share and the following characteristics: (Top

Left) Relation Specificity; (Top Right) Coefficient of Variation of the unit values for each prod uct;

(Bottom Right) min(entry, exit) in the export market for a given product; (Bottom Left) Country-

Product export tariffs. Observations are placed in 20 equally-sized bins. Coordinates of dots d isplay

the average of tariffs and intermediary export share of the data in each bin. Each panel reports

the coefficient, b, of a product-level univariate regression for intermediary export share. Robust

standard error is shown in parenthesis.

19

Intermediaries in International Trade

firms. On the contrary, the indirect mode of export would prevail if the traded good does n ot

require a relation-specific investment, as for commoditized products. T his prediction is in line

with the hypothesis put f orward by Peng and Ilinitch (2001) “the higher the commodity content of

the product, th e more likely that export intermediaries will be selected by manufacturers”. This

is confirmed by Figure 7 (top left) which shows a negative and s ignificant relationship between

intermediary export share an d the measure of relation specificity. Note that, given the very large

number of ob servations, data are binned in all plots of Figure 7, although the regression coefficients

are based on all the data.

The relation between p roduct price dispersion, as pr oxied by the coefficient of variation of

export unit values, and intermediary share is negative and significant, Figure 7 top right. This is

the expected relationship if lower price dispersion is associated with more homogeneous products

which are more likely to be hand led by intermediaries.

The plot at th e bottom left of Figure 7 displays the r elation between min(entry, exit) rate in

a product and intermediary export sh are. The negative and s ignificant slope suggests that easier

export entry and exit is associated with a lower export share f or wholesalers. Products that have

higher sunk costs of entry (low rates of entry/exit) are more likely to be handled by intermediaries.

Finally we consider the incidence of tariffs on the presence of intermediaries in product-country

pairs. The bottom right of Figure 7 shows the relation between product-country tariff and in-

termediary export share. There is a small, positive relation between product-country tariffs and

intermediary share.

The overall message of these figures is consistent with the idea that there is a systematic

relationship between the share of exports m an aged by wholesalers and both country and product

characteristics.

5.2 Selection into different modes of export

The previous section has investigated the univariate correlations of country and product charac-

teristics with the intermediary export s hare. This s ection and the next explore the relationship

between country and product characteristics and export participation and levels by wholesalers and

manufacturers.

Recent work on the importance of distance and GDP on the level of exports has emphasized

the role of firm selection, e.g. Helpman et al. (2008). The empirical literature on intermediation

has not considered selection effects. The iss ue is m ore difficult than the standard export problem in

that there are potentially different selection criteria for intermediary and d irect exporters. Ideally,

we would s ee the characteristics of the producing firm and th e choice of whether or not to export

and by what method. However, the trade data limits us to observing whether or not a product is

exported by wholesalers alone, manufacturers alone or by both methods. We pursue an admittedly

20

Intermediaries in International Trade

imperfect solution by first examining the relationship between pr oduct and country attributes and

the type of exporter and then examinin g how the value of exports varies between wholesalers and

manufacturers.

The theoretical framework outlined in Section 2 gives some guidance to the selection problem.

Four mutually exclusive situations might arise as fixed costs of exporting increase. If such costs are

zero, or very low, m anufacturers will choose to export directly. For higher fixed costs, some firms

will find it profitable to export in directly while some, more productive firms still export directly.

With suffi ciently high fix ed costs, a third outcome is possible where all firms go through wholesalers.

At the extreme, prohibitive fixed costs will result in no exports in th e product-country pair.

We rank the categories in order of increasing difficulty in entering the export market (direct

only, both dir ect and indirect, indirect only) and estimate an ordered probit model to investigate

the effects of country and product variables in determining the probability of being in one of the

three states,

Category

pc

= c + β

1

C

c

+ β

2

P

p

+ β

3

τ

pc

+ ε

pc

(6)

where Category

pc

accounts for the possible three ou tcomes described above, C

c

and P

p

are country

and prod uct variables, and τ

pc

is tariff to a particular country-product destination. Results are

reported in the first column of Table 8. While most of the coefficients have the predicted sign and

are significant, the proportional odds approach is easily rejected as indicated by the χ

2

test.

Given the rejection of the ordering of outcomes, column s 2 and 3 of Table 8 report the results

for a multinomial logit specification, where the baseline category is exports by manufacturers only.

Country GDP is positively associated with both type of firms serving the market but is negatively

associated with the likelihood of the market being served by wholesalers alone. Geographical

distance lowers the prob ab ility of both groups exporting relative to only manufacturing; comparing

only wholesalers to only manufacturing we find the same negative sign with a lower magnitude.

The measures of fixed costs of exports, Market Costs and Governance, behave as predicted by

the theory. Market Costs show the expected positive sign; higher market costs increase the probabil-

ity of both categories of firms exporting with r espect to the baseline category, only manufacturing,

and also increase the probability that wholesalers are the only exporters in the pr oduct-country

pair. Better country governance reduces the likelihood that the market will be served by both

wholesalers and manufacturers. Similarly, the Governance measure is negatively associated with

only wholesaling.

Looking at the product characteristics, we find the expected sign on the min(entry, exit) p roxy

for product-level sunk costs. Lower sunk costs reduce the probability of both categories exporting

relative to the baseline category and the same relation holds also for wholesalers versus manufac-

turers only. The effects of product price disper s ion and relation specificity are less clear and depend

21

Intermediaries in International Trade

on the groups being compared.

5.3 Product-country exports

This section investigates the effects of country and product characteristics on the level of exports

of manufacturers and wholesalers for product-country pairs. Columns 1 to 3 of Table 9 report

regression results with the log of country-product exports by exporter type, ln X

i

cp

, as dependent

variable and country and product characteristics, C

c

and P

p

, as explanatory variables, together

with a full set of interactions w ith the wholesaler dummy, D

W

,

ln X

i

cp

= c + δD

W

+ β

1

C

c

+ γ

1

C

c

∗ D

W

+ β

2

P

p

+ γ

2

P

p

∗ D

W

+ β

3

τ

pc

+ γ

3

τ

pc

∗ D

W

+ d

j

+ ε

cp

. (7)

Columns 1 and 2 add country and product fixed effects, respectively, while column 3 includes all

the available product and country characteristics.

25

Results on the country characteristics in column s 1 and 3 suggest that the level of exports of

both manufacturers and wholesalers exports is positively correlated with GDP, however the effects

are significantly lower for wholesalers. In contrast to Ahn et al. (2011), geographical distance affects

negatively the value of trade equally for both types of firms.

26

The results on Market Costs and Governance are in line with the theoretical predictions. Inter-

mediaries’ exports increase with market costs, suggesting that wholesalers are better able to spread

fixed costs across produ cts. The country governance indicator yields a similar pattern of results:

better governance is associated with higher exports from manufacturers but that effect is greatly

reduced or disappears entirely for wholesalers.

Columns 2 an d 3 of Table 9 report the r esults on the p roduct characteristics. We focus on

the sign and significance of the interaction term s with the wholesaler dum my. Wholesalers export

relatively less in products w ith lower sun k entry costs, i.e. greater min(entry, exit), higher price

dispers ion, and higher relationship specificity. All th ese coefficients have the expected signs and

point to product characteristics playing an important part in the endogenous choice of firms to

export directly or through an intermediary.

Finally, we include tariffs in column 3. As expected, the coefficient of tariffs exhibits a negative

sign; firms export less in country-product pairs with higher tariffs. The wholesaler interaction is

positive but not significant.

This section has examined th e role of country and product characteristics in the choice of

the mode of export and the magnitude of country-product exports. Results confir m the findings

of p revious studies th at country-specific fixed export costs are correlated with the use of export

25

In Column 3 we cluster both on countries and products using cluster2 packages for Stata (Petersen; 2009).

26

The specification of Ahn et al. (2011) is slightly different as they include a smaller set of covariates and do not

include the interacted wholesale dummy.

22

Intermediaries in International Trade

intermediaries. We further show that the quality of the more general contracting environment is

related to the choice of mo de of export. Exports through an intermediary are more likely wh en the

quality of the general contracting environment of the country is weak.

We also show that the characteristics of the product play a role in determining the choice of

export mode. Lower contract intensity, greater product homogeneity, and higher produ ct-level sunk

costs of exporting are associated with a greater reliance on intermediaries in exporting.

6 Intermediaries and exogenous shocks

We have documented the variation in the share of indirect exports across countries and products.

The results support the id ea that export intermediaries arise in large p art because of the presence

of s ignificant fixed export costs at the country and product level. In addition, product adding an d

product dropping in the export market are greater for wholesale exporters than for manufacturers.

Taken together this evidence suggests that a common sh ock to profits across destinations, e.g.

a common tariff cut, may have different effects both across types of exporting firms and in the

aggregate across countries due to variation in the composition of exporters.

This section examines whether intermediaries and manufacturers respon d differently to exoge-

nous cur rency shocks. Using annual fluctuations in bilateral real exchange rates as measures of

exogenous changes in export profitability, we investigate th e effects on firms’ export behavior. We

consider the impact of exchange rate changes on fir m exports to country c, as well as on the number

of exported products and the average value of exports to that destination. Following Bernard et al.

(2007) a firm’s total exports to a destination can be decomposed into extensive and intensive

margins,

ln X

fc

= ln P rod

fc

+ ln avgX

fc

(8)

where ln X

fc

is th e log of total exports by firm f to country c, P rod

fc

is th e number of distinct

HS6 products exported by firm f to country c, and avgX

fc

is th e average exports per exporting

firm f to country c. We regress the annual log change from 2000 to 2007 of firm total exports to

country c and the annual changes of the two components on a dummy for wholesaler (D

W

ft

), the

change in the log of the real bilateral exchange rate of the Italian currency (∆ln RER

ct

) and their

interaction

∆ln X

fct

= c

1

+ δ

1

D

W

ft

+ β

1

∆ln RER

ct

+ γ

1

∆ln RER

ct

∗ D

W

ft

+ d

j

+ ε

1

fct

(9)

∆ln P rod

fct

= c

2

+ δ

2

D

W

ft

+ β

2

∆ln RER

ct

+ γ

2

∆ln RER

ct

∗ D

W

ft

+ d

j

+ ε

2

fct

(10)

∆ln avgX

fct

= c

3

+ δ

3

D

W

ft

+ β

3

∆ln RER

ct

+ γ

3

∆ln RER

ct

∗ D

W

ft

+ d

j

+ ε

3

fct

(11)

23

Intermediaries in International Trade

where d

j

indicates a set of fi x ed effects. Using data from the International Financial Statistics

database (IMF, 2010), we defi ne the RER

ct

index for each year:

RER

ct

= ER

ct

CP I

t

CP I

ct

where ER

ct

is the nominal Italian exchange rate expressed as the number of foreign currency

units per home currency unit and

CP I

t

CP I

ct

is the ratio of the domestic consum er price level and

the consumer price index abroad.

27

An upward (downward) movement therefore represents an

appreciation (depreciation) of the domestic currency.

Table 10 reports results from estimating equations 9-11. Since real exchange rate variations

inside the Eurozone are related only to price levels changes and given the relevant role of wholesalers

in Extra-EU destinations, we include in the regressions only countries ou tside the E U.

The first two columns of Tab le 10 present the r esults for export value, including country and year

fixed effects (column 1) and country and firm fixed effects (column 2). Exchange rate movements

have the expected effects on firm exports to country c: an appreciation of the euro currency is

associated with a decrease in firm exports. However, the interaction of wholesaler type and the real

exchange rate is positive and signifi cant in both columns; firm exports fall less (3.7-8.4 percent) for

intermediaries than for manufacturers when the Italian currency appreciates.

Looking at columns 3-6 we observe that, for both manufacturing and wholesale firms, the fall in

exports in respon se to an appreciation of the domestic currency is driven both by a decrease in the