* The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be reported as or

attributed to the International Monetary Fund, its Executive Board, or the governments

of any of its member countries.

Gulf Cooperation Council

Trade and Foreign Investment—Keys to Diversification and Growth

in the GCC

Prepared by Staff of the International Monetary Fund

I N T E R N A T I O N A L M O N E T A R Y F U N D

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

2 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

CONTENTS

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY __________________________________________________________________________ 3

A. Introduction ___________________________________________________________________________________ 4

B. Recent Trends in Foreign Trade and Investment _______________________________________________ 4

C. Foreign Trade and Investment Environment __________________________________________________ 12

D. Growth Impact of Enhanced Foreign Trade and investment __________________________________ 21

E. Concluding Remarks __________________________________________________________________________ 28

BOXES

1. Tapping Greater FDI Inflows: The Case of Singapore __________________________________________ 18

2. Boosting Intra-GCC Non-Oil Trade ____________________________________________________________ 23

FIGURES

1. Trade and FDI __________________________________________________________________________________ 5

2. Trade Openness ________________________________________________________________________________ 5

3. Composition of GCC Export of Goods, 2016 ___________________________________________________ 7

4. Quality and Concentration of Exported Goods _________________________________________________ 8

5. Product Complexity of Exports _________________________________________________________________ 9

6. Intra-GCC Trade in Goods, 2012–16 ____________________________________________________________ 9

7. Trade in Services, 2000–17 ____________________________________________________________________ 10

8. Trade in Services by Type _____________________________________________________________________ 10

9. FDI Flows ______________________________________________________________________________________ 11

10. Foreign Direct Investment ___________________________________________________________________ 11

11. Evolution of the GCC Supra-National Trade and Investment Policies ________________________ 12

12. Direct and Indirect Trade and FDI Barriers ___________________________________________________ 14

13. Average Public Procurement Indicators, 2017 ________________________________________________ 19

14. Logistics Performance Index, 2018 ___________________________________________________________ 20

15. Potential and Actual Exports _________________________________________________________________ 22

16. Export Diversification and Sophistication ____________________________________________________ 22

17. Average Monthly Earnings ___________________________________________________________________ 24

18. Human Capital _______________________________________________________________________________ 25

19. Non-Tradable Services and Export Gaps, 2015 _______________________________________________ 25

20. Trade Barriers and Business Climate _________________________________________________________ 26

21. FDI Inflows ___________________________________________________________________________________ 27

TABLE

1. Enabling Trade Index and Subcomponents, 2016 _____________________________________________ 15

APPENDICES

I. Export Indices __________________________________________________________________________________ 30

II. Regression Analysis ___________________________________________________________________________ 32

References _______________________________________________________________________________________ 39

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 3

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

1

Diversification of the GCC economies, supported by greater openness to trade and higher

foreign investment, can have a large impact on growth. Such measures can support higher,

sustained, and more inclusive growth by improving the allocation of resources across sectors and

producers, creating jobs, triggering technology spillovers, promoting knowledge, creating a more

competitive business environment, and enhancing productivity.

The GCC countries are open to trade, but much less so to foreign direct investment (FDI).

GCC foreign trade has been expanding robustly, but FDI inflows have stalled in recent years

despite policy efforts taken to reduce administrative barriers and provide incentives to attract

FDI. Tariffs are relatively low; however, a number of non-tariff barriers to trade persist and there

are substantial restrictions on foreign ownership of businesses and real estate.

The growth impact of closing export and FDI gaps could be significant. In most countries,

the biggest boost to growth would come from closing the FDI gap—up to one percentage point

increase in real non-oil per capita GDP growth. Closing export gaps could provide an additional

growth dividend in the range of 0.2-0.5 percentage point.

Boosting non-oil exports and attracting more FDI requires a supportive policy

environment. Policy priorities are to upgrade human capital, increase productivity and

competitiveness, improve the business climate, and reduce remaining barriers to foreign trade

and investment. Specifically, continued reforms in the following areas will be important:

• Human capital development: continue with investments made to raise educational quality to

provide knowledge and skills upgrade.

• Labor market reforms: aim to improve productivity and boost competitiveness of the non-oil

economy.

• Legal frameworks: ensure predictability and protection; efforts should include enhancing

minority investor protection and dispute resolution; implementing anti-bribery and integrity

measures.

• Business climate reforms: focus on further liberalizing foreign ownership regulations and

strengthening corporate governance; and on further reducing non-tariff trade barriers by

streamlining and automating border procedures and streamlining administrative processes

for issuing permits.

1

Prepared by a team led by Vahram Stepanyan, comprising Botir Baltabaev, Anastasia Guscina, Mohammed

Zaher, Ling Zhu, and Tucker Stone, under the supervision of Bikas Joshi (all MCD). Diana Kargbo-Sical provided

editorial support.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

4 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

A. Introduction

1. Most countries in the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) have made limited progress

in diversifying their economies away from hydrocarbons.

2

On average for the region during

2000-2017, oil revenues were close to 80 percent of government revenues, oil exports amounted

to 65 percent of total exports, and oil GDP represented 42 percent of total GDP.

3

This picture was

broadly unchanged during 2011–17. There is a need to diversify the economies of the GCC to

reduce exposure to volatility and uncertainty in the global oil market, help create private sector

jobs, and increase productivity and sustainable growth (Callen et al., 2014).

2. Higher foreign trade and investment can play a large role in boosting

diversification and growth. Several studies link greater trade openness to higher per capita

income (Frankel and Romer, 1999; Feyrer, 2009; Cerdeiro and Komaromi, 2017), while FDI can

boost growth by triggering technology spillovers, promoting knowledge, creating a more

competitive business environment, and enhancing productivity (OECD, 2002; WEF, 2013). Further

reducing barriers to foreign trade and investment to broaden and upgrade their export bases can

help GCC countries better integrate into global value chains and make their economies more

productive (IMF, 2017b).

3. This paper helps identify policy reform priorities to support diversification and

growth in the GCC through exports and foreign investment. The paper is organized as

follows: Section B outlines recent trends in foreign trade and foreign direct investment (FDI) in

the GCC; Section C discusses the evolution of policy frameworks and business environment for

foreign trade and FDI; Section D analyses export and FDI determinants and provides estimates of

the GCC economies’ potential exports and FDI inflows as well as growth impact from boost to

exports and FDI; Section E concludes with policy priorities.

B. Recent Trends in Foreign Trade and Investment

The GCC economies’ foreign trade has expanded robustly, but export quality and diversification

remain relatively low. Meanwhile, FDI inflows into the GCC have been concentrated in a limited

number of countries and sectors and have weakened in recent years.

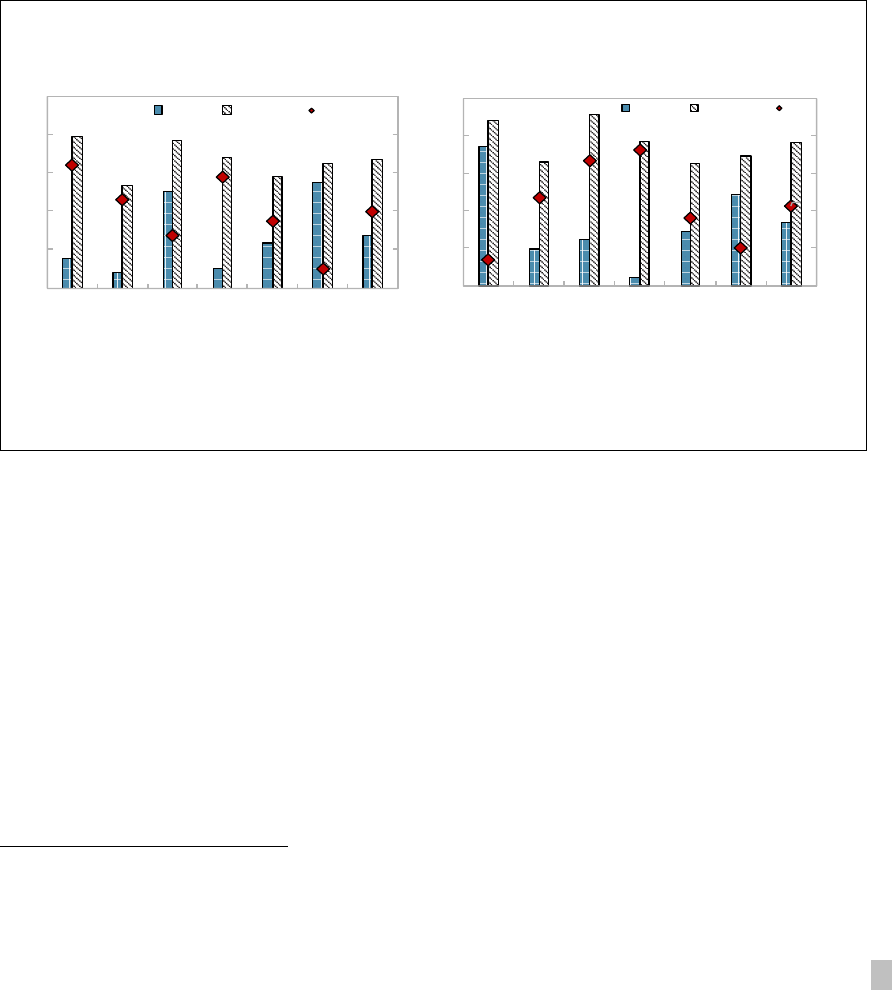

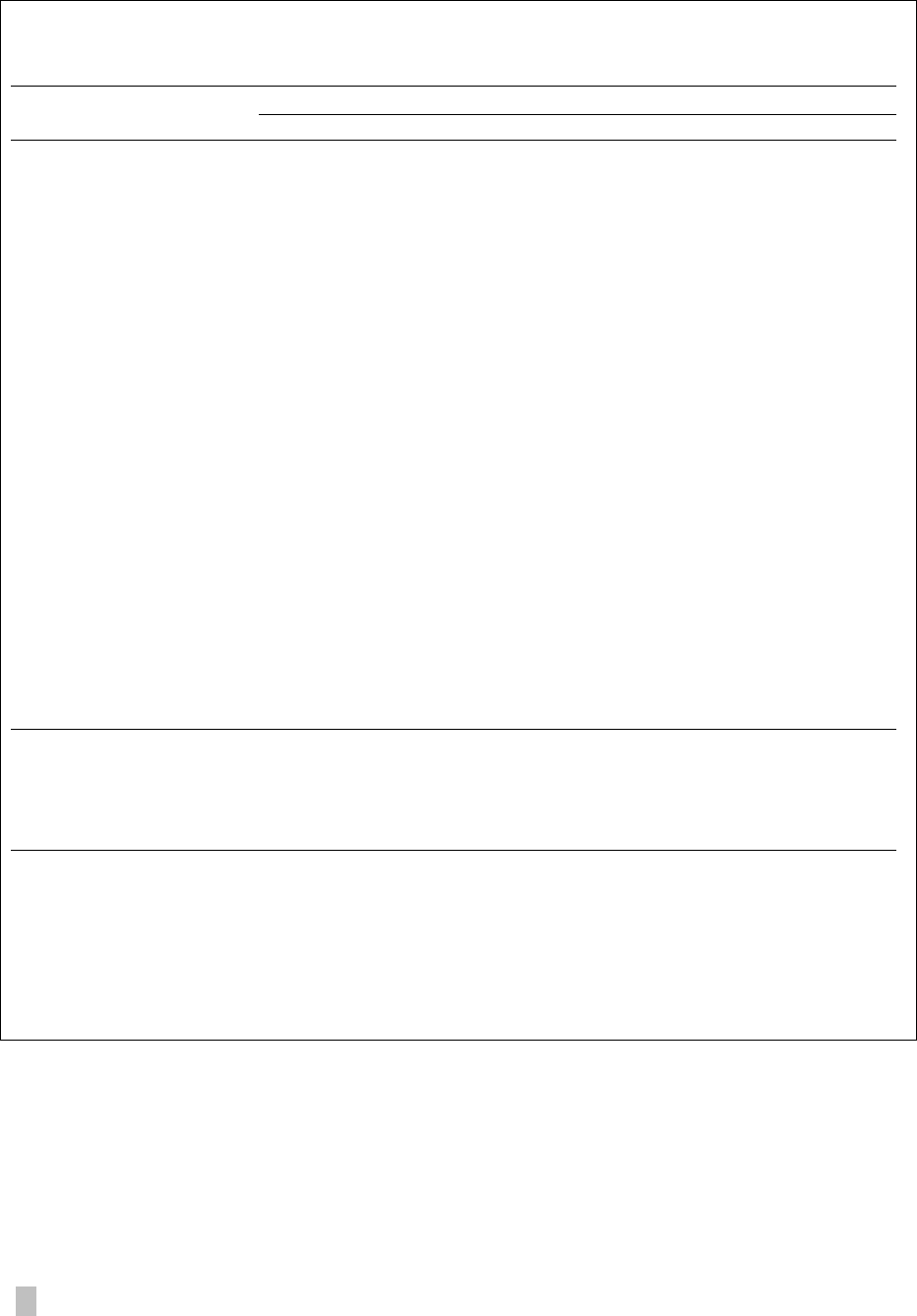

4. While trade between the GCC and the rest of the world has expanded robustly, FDI

inflows into the region have stalled in recent years. Since 2000, the GCC’s trade in goods and

services grew at an average real rate of 7.5 percent, almost twice that of real GDP growth,

compared with the global averages of 4.8 percent and 3.8 percent, respectively. The oil price

boom during 2003-2008 led to a sharp increase in oil export receipts which in turn led to a

significant expansion in imports of goods and services during that period. This growth in trade

was interrupted during the global financial crisis, but has rebounded strongly since then, largely

2

In this paper “hydrocarbon” is used interchangeably with “oil”.

3

Recently, countries have been implementing policies to increase non-oil fiscal revenues. In particular, Saudi

Arabia and UAE introduced a value-added tax in 2018.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 5

driven by solid domestic demand and improvements in global conditions. On the other hand,

after surging in the early 2000s, FDI inflows into GCC countries have stalled, remaining on

average below 2 percent of regional GDP (Figure 1).

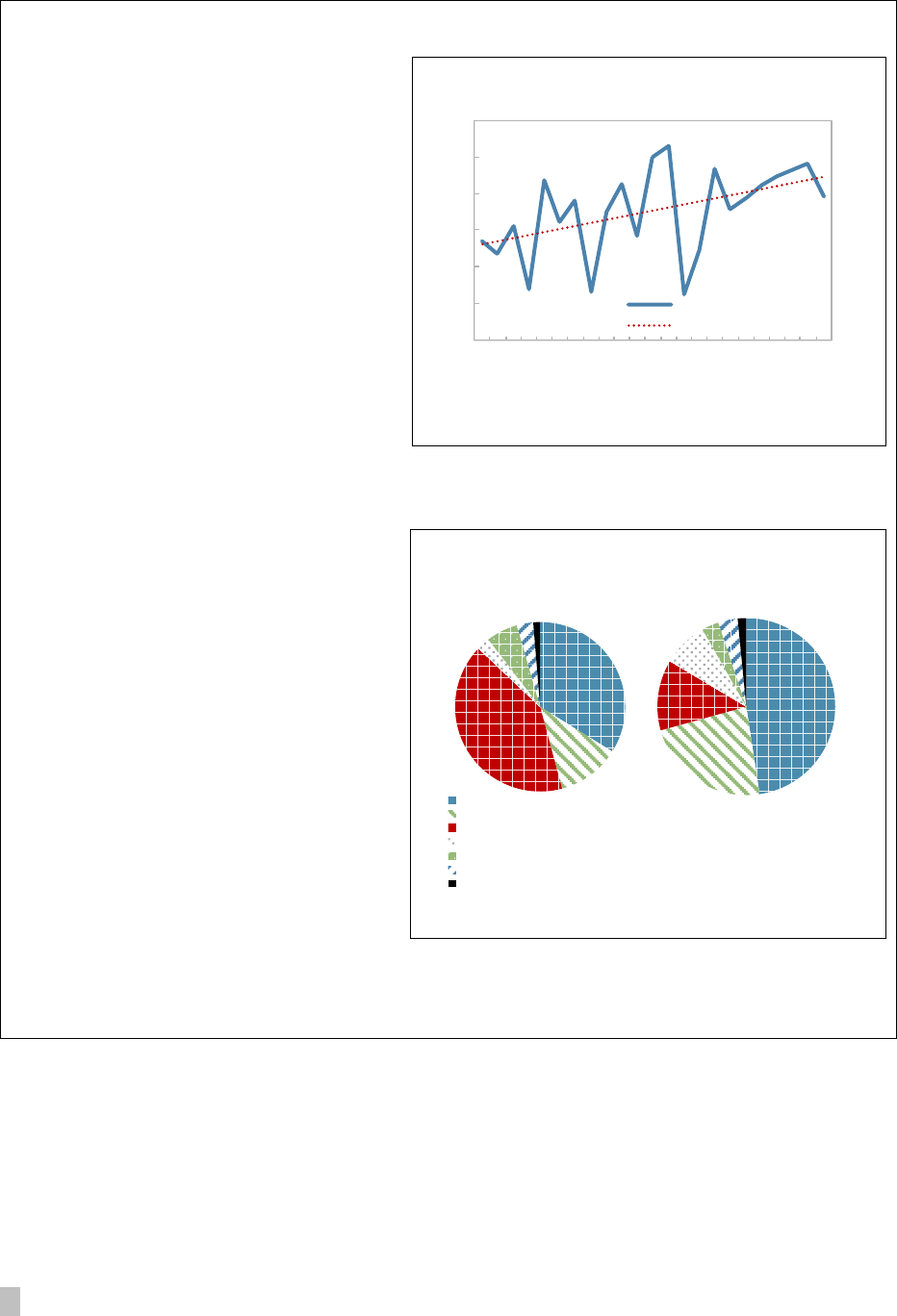

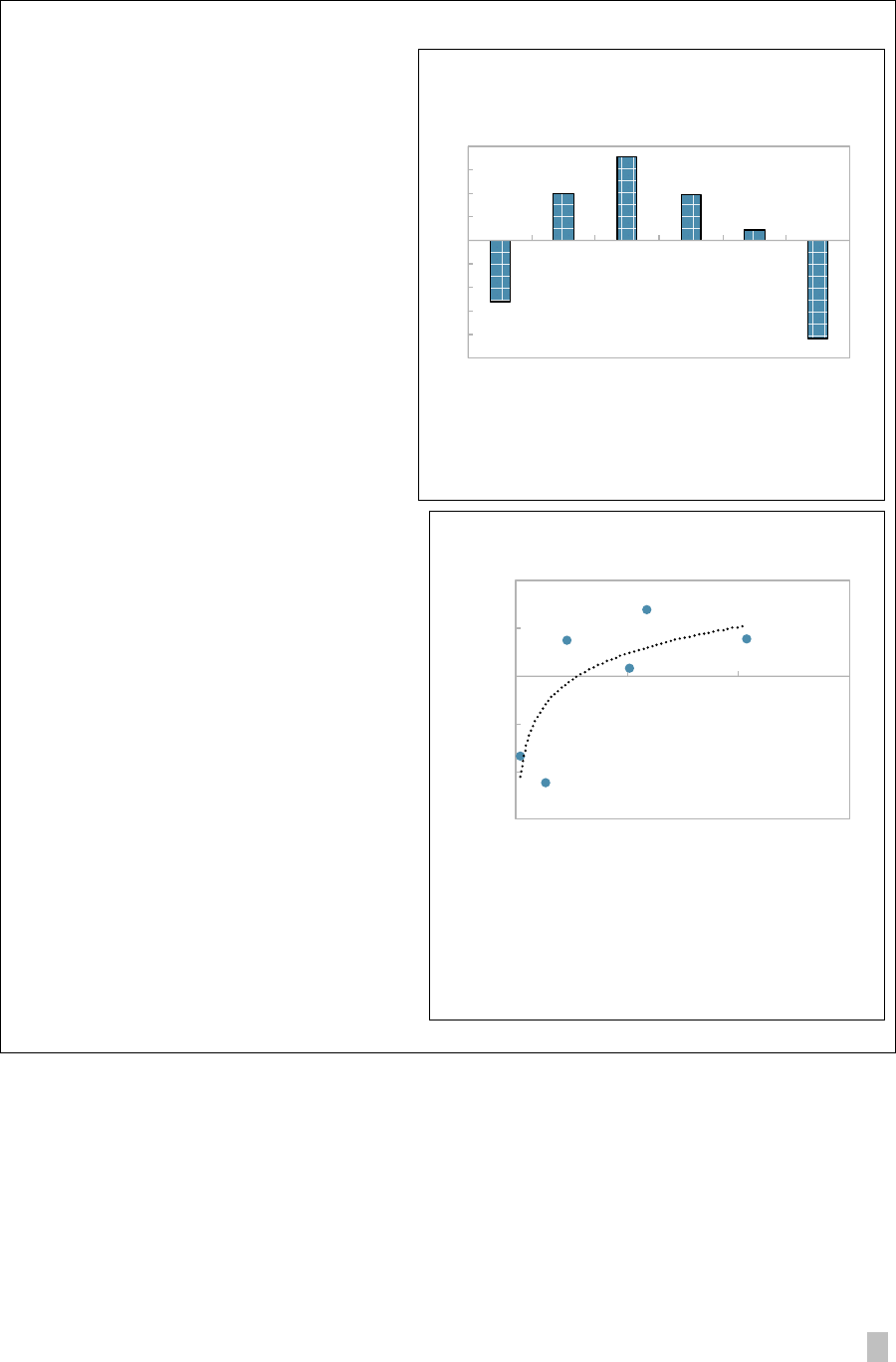

Figure 1. GCC: Trade and FDI

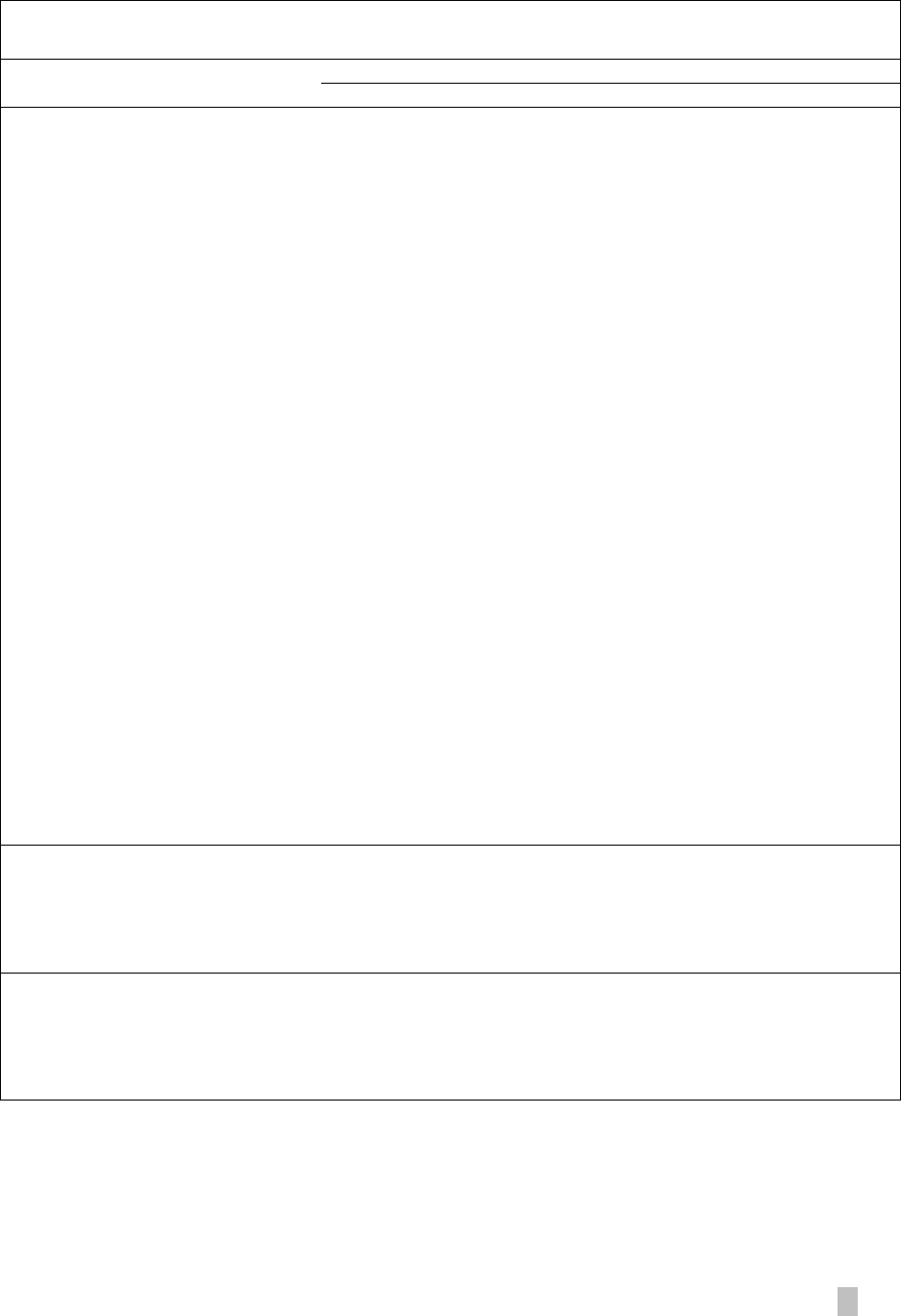

5. The GCC countries are highly engaged in trade. The ratio of exports and imports of

goods and services to GDP exceeded 100 percent in 2017, well above the average of 50 percent

for emerging economies (Figure 2). This largely stems from the region’s large hydrocarbon

resources, mostly exported, and a lack of diversification in domestic production, necessitating

imports.

Figure 2. GCC: Trade Openness

BHR

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

KWT

0

50

100

150

200

250

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

World GCC EMs

GCC Trade Openess, 2000-2017

(Su m of exports an d imports as percent of GDP)

Sou rces: World Economic Outlook; and IMF staff calculations.

0

50

100

150

200

250

GCC BHR KWT OMN QAT SAU UAE

2000 2012 2017

GCC Trade Openess, 2000-2017

(Sum of non-oil exports and total imports as percent of non

-oil G DP)

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

400

450

500

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

Real imports of goods and services

Real exports of goods and services

Real GDP

Real non-oil GDP

GCC Real Trade of Goods and Services and GDP, 2000-17

(Index, 2000=100)

Sources: World Economic Outlook; Country authorities; and IMF staff calculations.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

GCC FDI Inflows, 2000

-2017

(In USD billion)

UAE Saudi Arabia

Qatar Oman

Kuwait Bahrain

GCC (Percent of GDP, RHS)

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

6 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Trade in goods

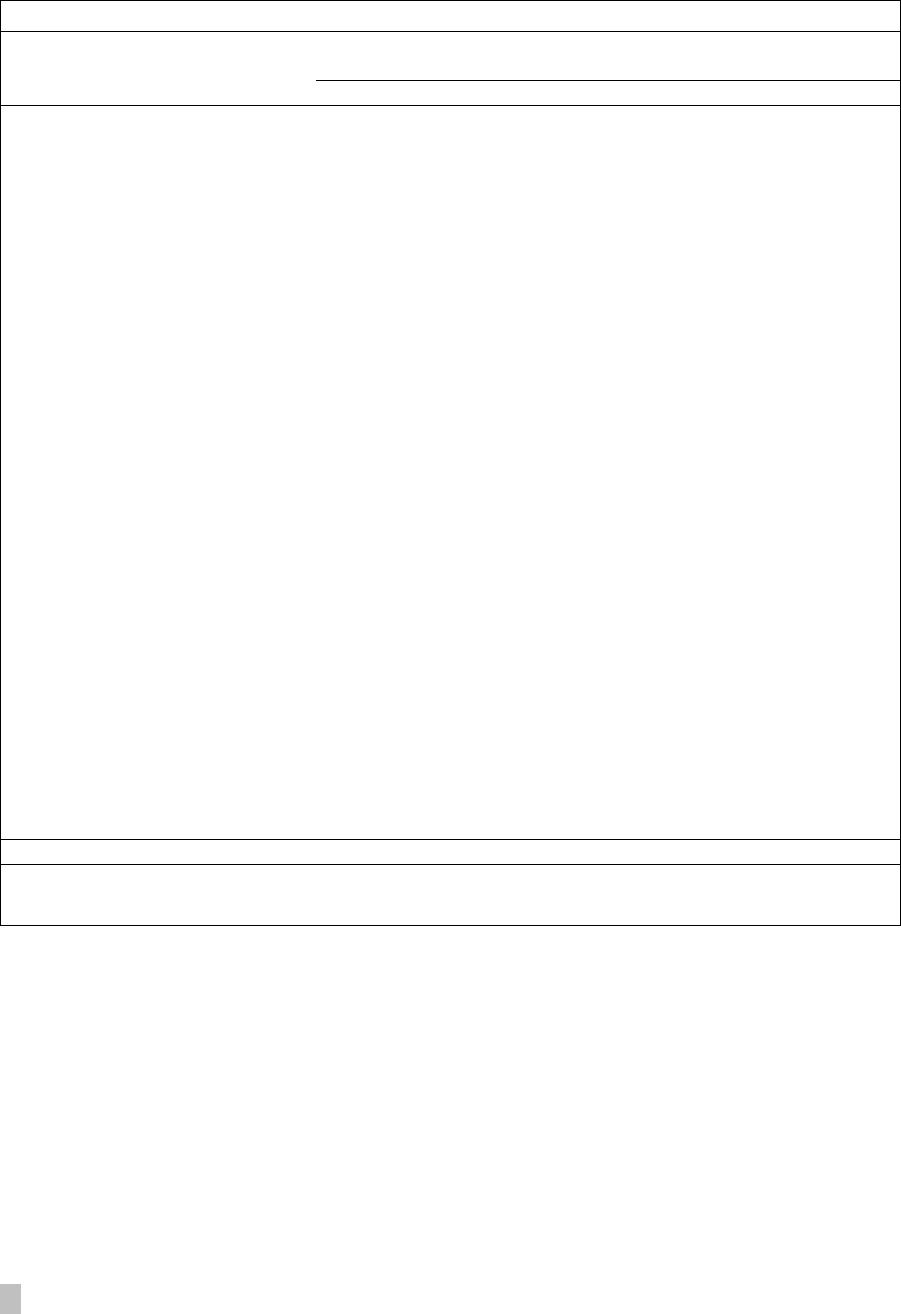

6. The GCC countries are predominantly exporters of hydrocarbons. With some of the

world’s largest hydrocarbon reserves, most GCC countries (except the UAE and Bahrain) have the

bulk of their total exports concentrated in oil and gas, with the share of the latter ranging

between 70 to 80 percent in Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia (Figure 3).

7. Non-hydrocarbon exports have increased, with some transition from raw materials

to intermediate goods. Non-oil exports (including re-exports) have increased, from 16 percent

of non-oil GDP in 2000 to 32 percent in 2017, though they remain a small share of global non-oil

trade. This robust growth has been concentrated in capital-intensive downstream industries—

petrochemicals, refined hydrocarbons, aluminum—that directly capitalize on the region’s

competitive advantage in abundant hydrocarbons and subsidized energy. The share of exported

raw materials accordingly has been declining in favor of intermediate and consumer goods. Re-

exports of goods make a non-negligible share in total GCC exports of goods and services (about

a fifth), primarily explained by their very high share in the UAE exports; however, this paper does

not focus on this aspect of foreign trade as it strives to assess the export potential from the

perspective of creating substantial value added for the GCC economies.

8. The GCC is establishing itself as a significant supplier of petrochemicals, aluminum,

and some minerals. SABIC of Saudi Arabia, for example, is one of the world’s largest

petrochemicals manufacturers while ALBA of Bahrain is among the largest aluminum smelters in

the world. Oman has become the world’s largest exporter of gypsum in 2017. The region

continues to maintain a revealed comparative advantage (RCA) (for definition, see Appendix I) in

primary commodities, including fuel, metals and minerals. In 2016, the number of products with

RCA ranged between 31 in Qatar and 172 in the UAE. The sectoral distribution of exports also

shows that Saudi Arabia has RCA in plastic and rubber exports, Bahrain, Oman and UAE in metals

and minerals, and UAE in stone and glass. Other non-oil exports are small and scattered among

various categories. Meanwhile, GCC countries have achieved less success in exporting other

manufactured goods, reflecting relatively small direct involvement in the global value chains.

9. The value-added and diversification of non-oil exports remain relatively low. Export

quality, a proxy for value-added, (for definition, see Appendix I) has increased in all GCC

countries over the last 15 years, though at varying degrees, but generally remains low compared

to emerging market averages (Figure 4). During the same period, most GCC economies saw

limited reduction in export concentration indices (with the exception of the UAE and Oman) and

when compared to other emerging markets, GCC’s overall non-oil exports appear more

concentrated.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 7

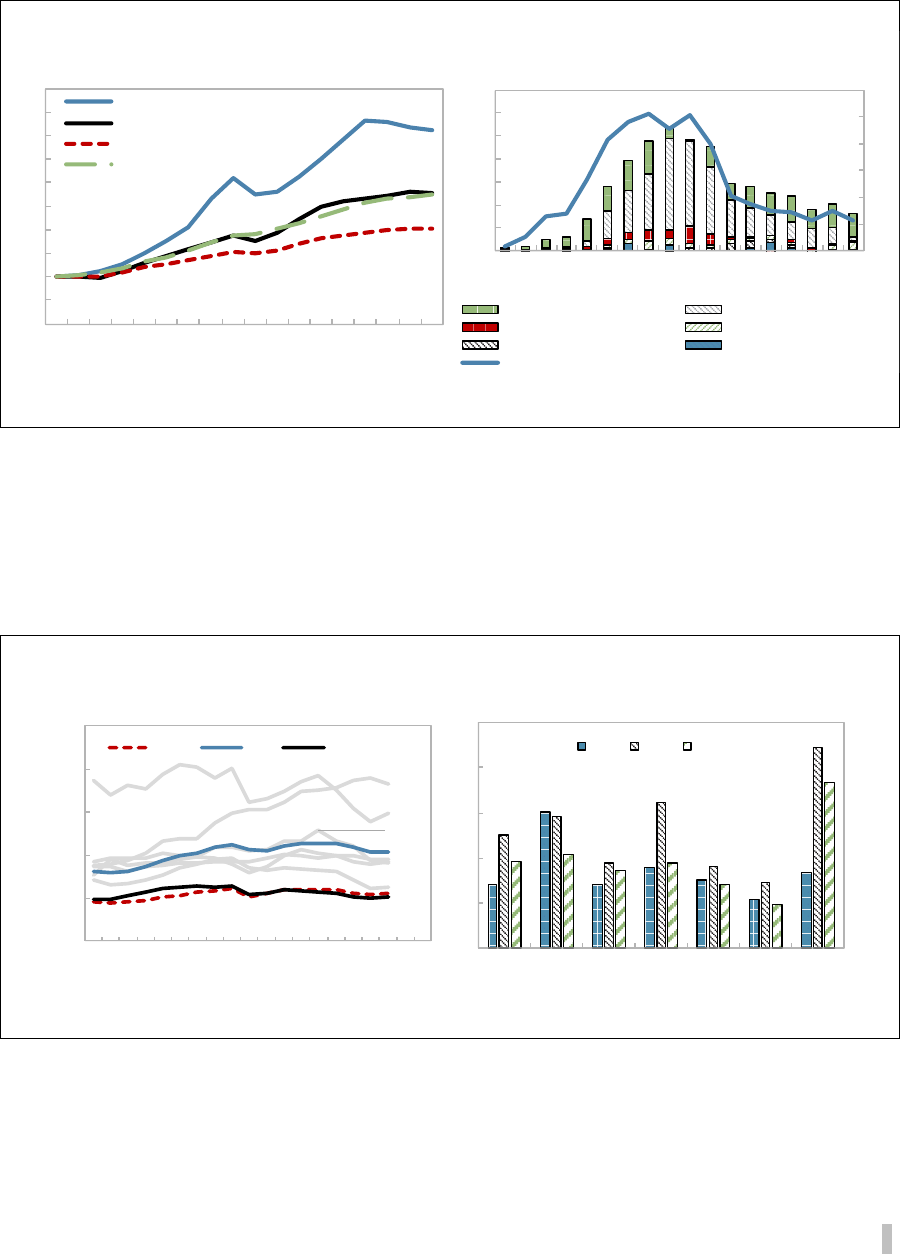

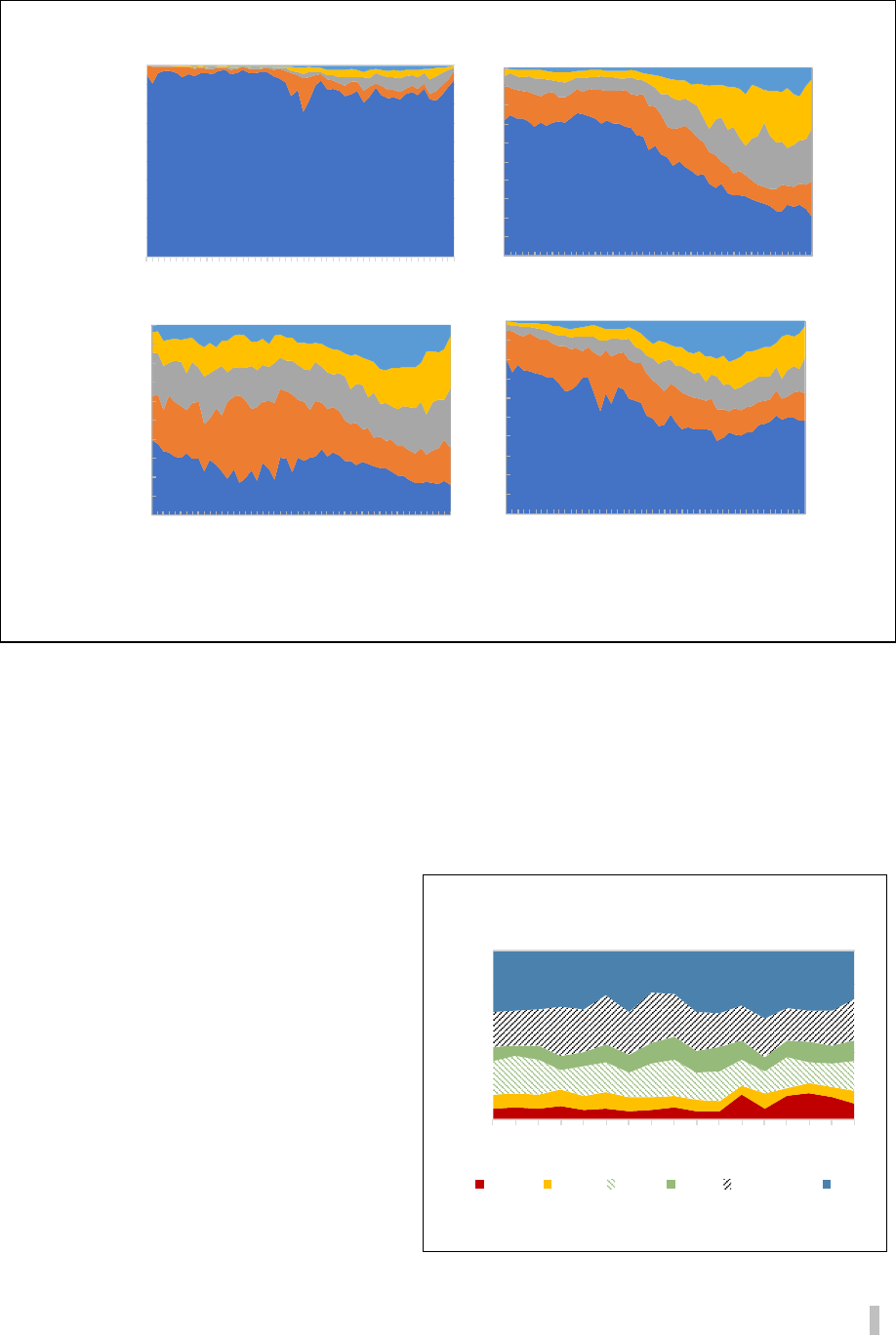

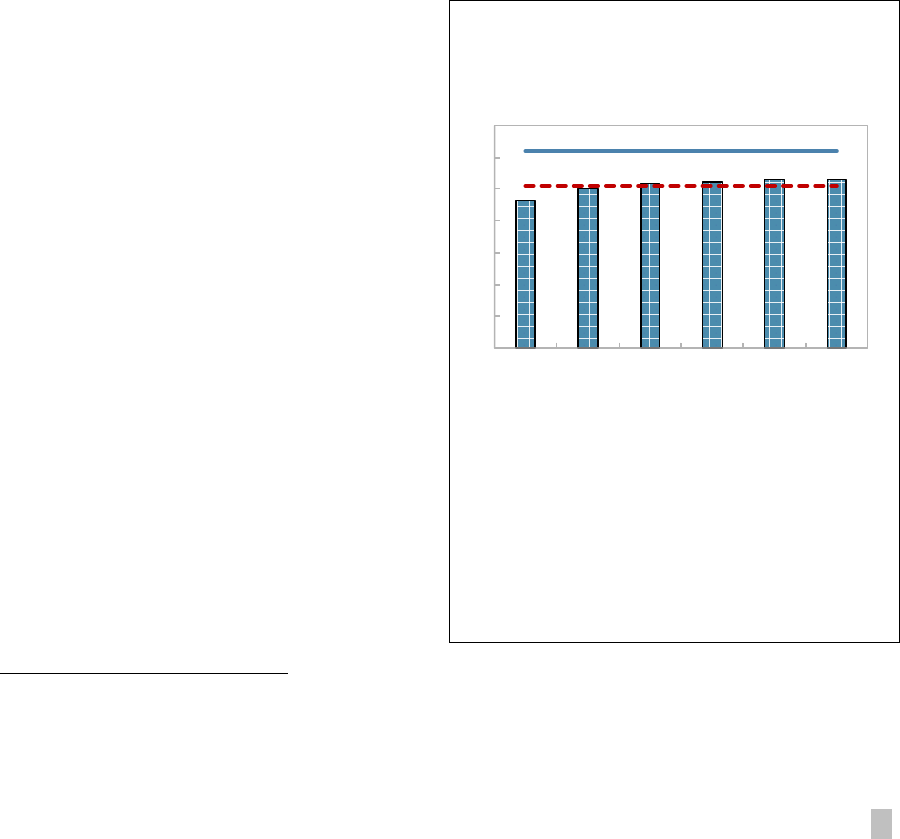

Figure 3. Composition of GCC Export of Goods, 2016 1/

Bahrain

Kuwait

Oman

Qatar

Saudi Arabia

United Arab Emirates

________________________

Sources: Atlas of Economic Complexity; and UN COMTRADE.

1/ Data according to Standard International Trade Classification (SITC1).

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

8 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

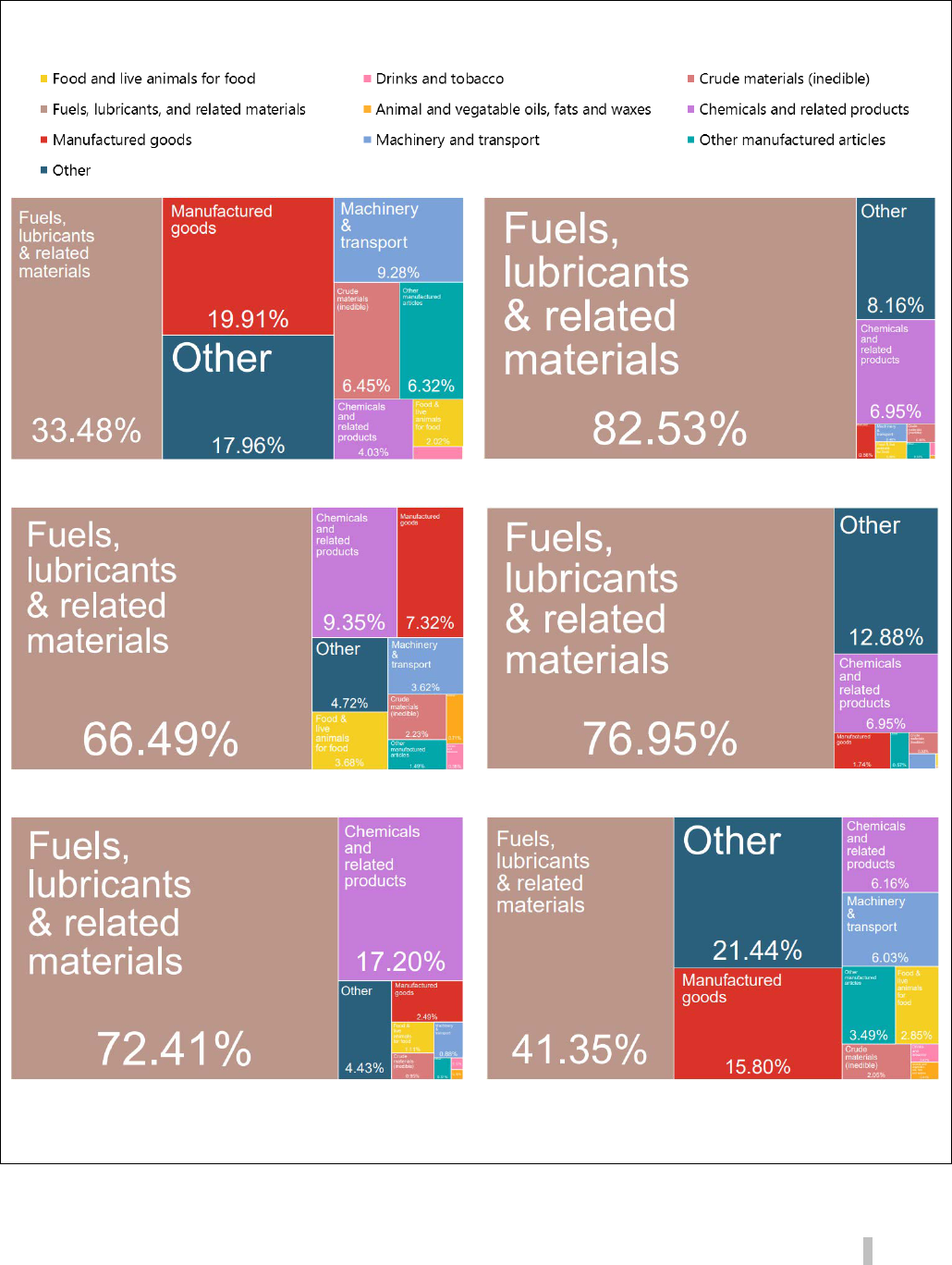

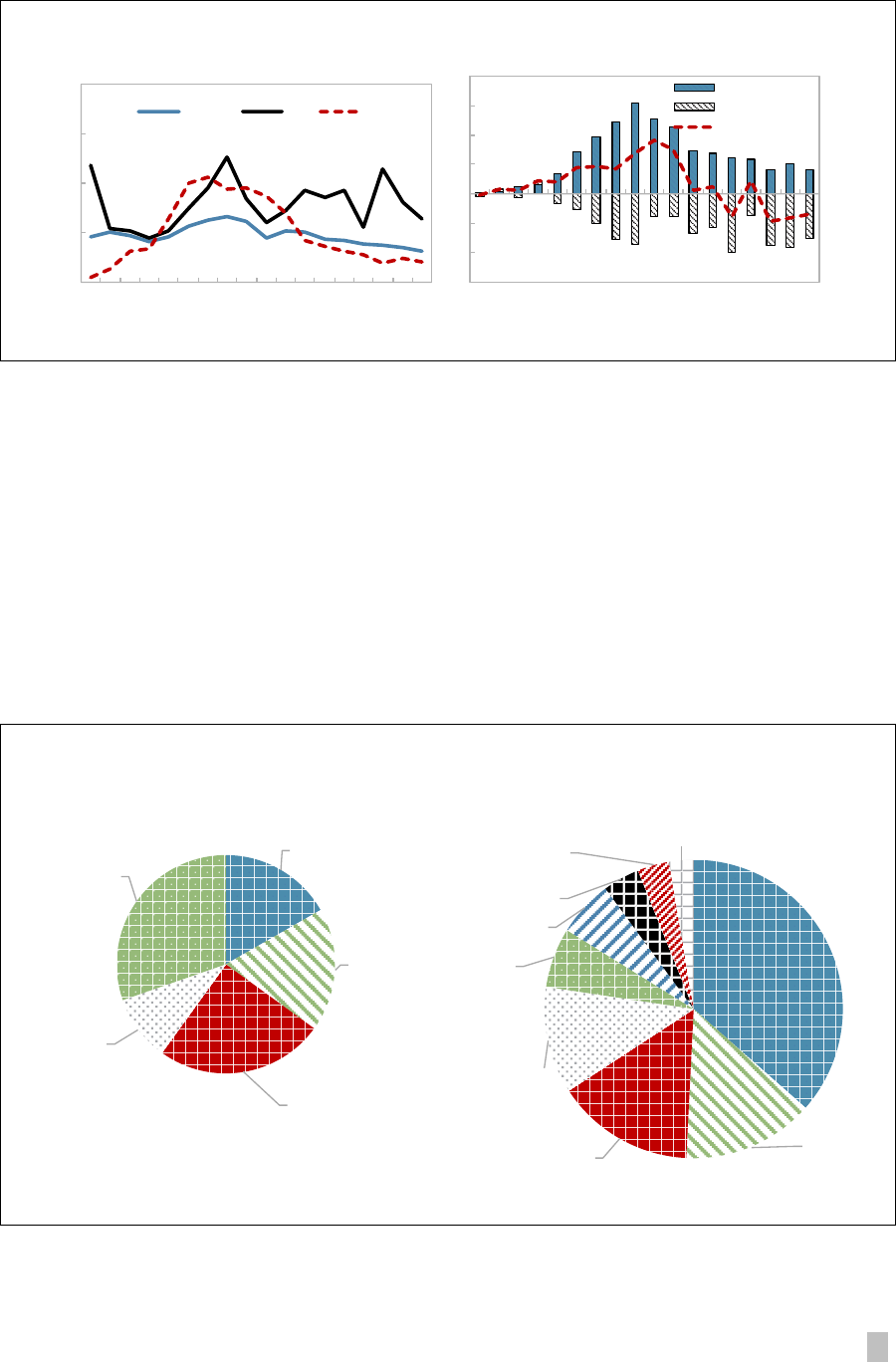

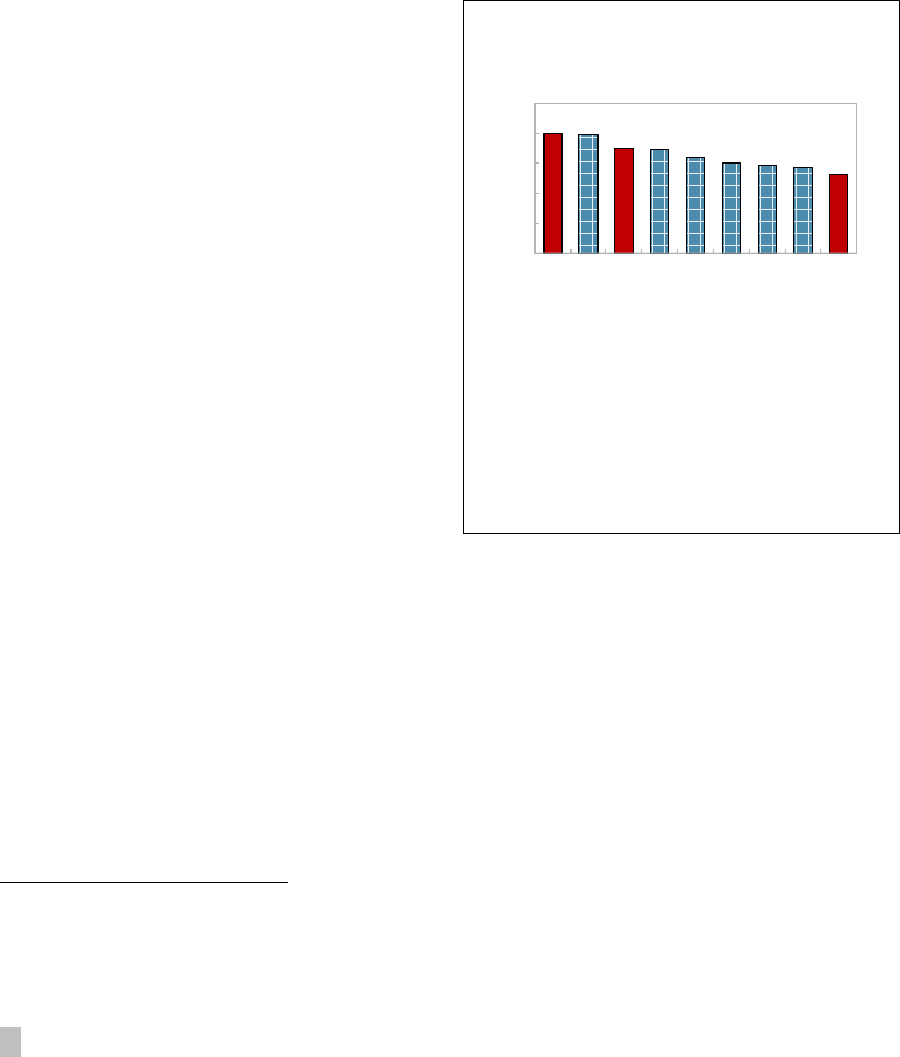

Figure 4. GCC: Quality and Concentration of Exported Goods

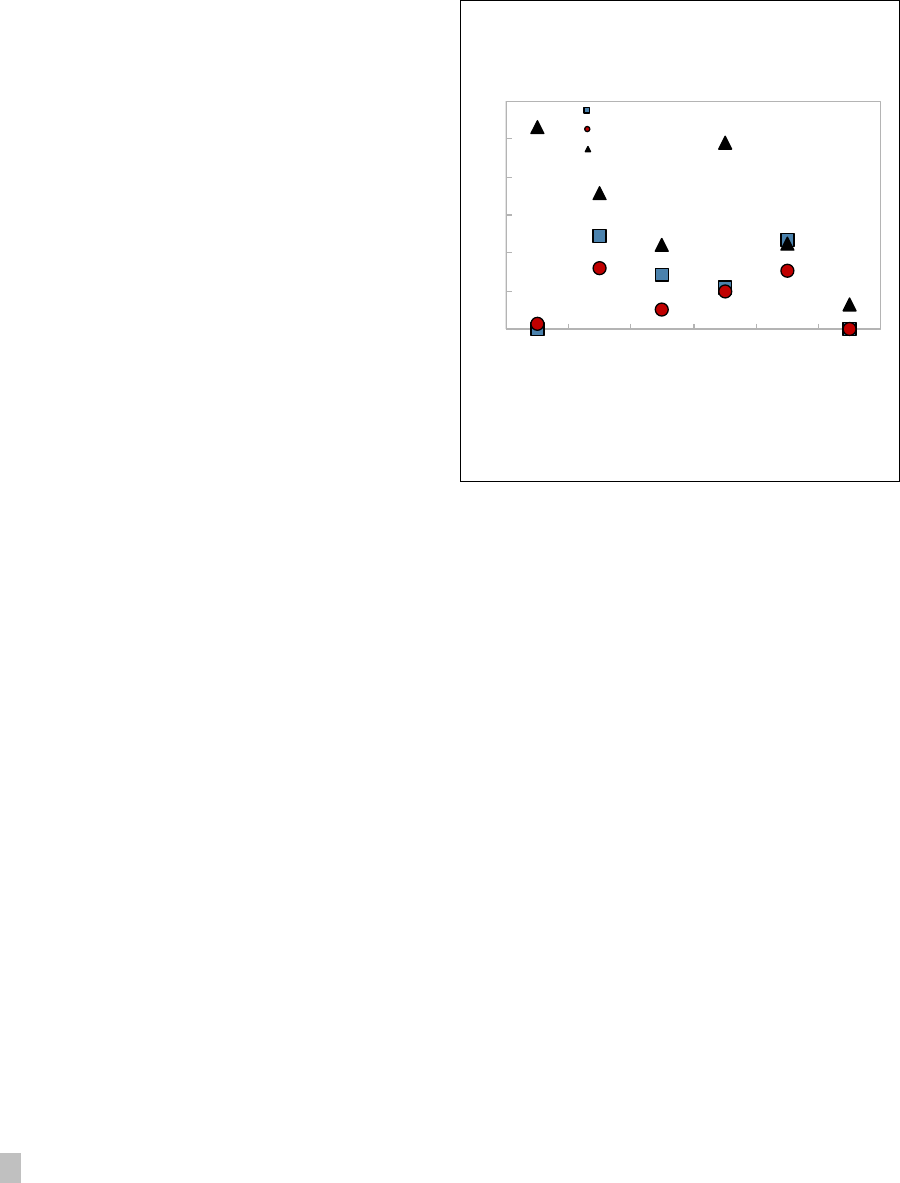

10. The GCC lags other regions in export sophistication. The export product complexity

index (for definition, see Appendix I), which looks at the share of knowledge-intensive products

in the export basket, shows the level of sophistication of a country’s goods exports which is

found to be associated with higher income levels (Henn et al., 2013). The least complex products

(lowest quintile) accounted for more than 90 percent of the value of exports in 2013, the latest

year for which data is available, in contrast to emerging economies in Latin America and Asia,

and the share of the most complex products (top quintile) in the GCC was close to zero

(Figure 5).

11. The large hydrocarbon endowments as well as low diversification and

sophistication of exports could partly explain the limited integration of the GCC into

global value chains (GVCs). While the UAE has made more headway than others in diversifying

its economy, evidence shows that in most GCC economies indicators of economic complexity,

diversity, and export quality are lower when compared to many emerging market economies,

including other oil producers and countries in the region. Like in many other emerging market

commodity-exporters, the GCC exports, dominated by hydrocarbons, largely participate in the

early stages of GVCs while a limited participation in the final stages of GVCs means a relatively

small share of foreign value added in the GCC exports. Other impediments to greater integration

into global value chains are discussed in Section III.

Sources: IMF, Export Diversification and Quality Dataset;

national authorities.

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

1.0

1.1

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

Bahrain

Kuwait Oman

Qatar

SAU UAE

Shaded area is EM average

Export Quality, 2000–14

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

Bahrain Kuwait Oman

Qatar SAU UAE

Shaded area is EM average

So u rces: UNCTAD.

1/ Lower index indicates

lower concentration and higher

diversification.

GCC Export Concentration Index, 2000–16 1/

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 9

Figure 5. GCC: Product Complexity of Exports 1/

12. The GCC economies’ imports far exceed their non-oil exports. The GCC countries

remain heavily dependent on imports to meet their consumption and investment needs.

Machinery and transport equipment (34 percent of total) comprise GCC’s main imports followed

by manufactured goods and articles (24 percent) and food (9 percent). With imports consistently

exceeding non-oil exports, GCC countries’ non-oil trade balance has been in constant deficit

(about 11 percent of non-oil GDP in 2017).

13. Intra-GCC trade in goods remains

modest. Notwithstanding the low trade

barriers under the GCC common market

agreement since 2008, intra-GCC non-oil

trade remains low, at only 10 percent of

total non-oil trade in 2016. This suggests

that complementarities within the region

are weak, most probably due to similar

economic structures and levels of economic

development. Out of the $85 billion intra

GCC trade in 2016, the UAE accounts for

the largest share, highlighting its role as a

major re-exporting hub, followed by Saudi

Arabia and Oman (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Intra-GCC Trade in Goods, 2000–16

(Country share, percent)

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

Bahrain Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi Arabia UAE

Sources: UN Comtrade; and IMF staff calculations.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1962

1965

1968

1971

1974

1977

1980

1983

1986

1989

1992

1995

1998

2001

2004

2007

2010

2013

Latin America and Caribbean

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1962

1965

1968

1971

1974

1977

1980

1983

1986

1989

1992

1995

1998

2001

2004

2007

2010

2013

Emerging Asia

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1962

1965

1968

1971

1974

1977

1980

1983

1986

1989

1992

1995

1998

2001

2004

2007

2010

2013

Emerging Europe

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1962

1965

1968

1971

1974

1977

1980

1983

1986

1989

1992

1995

1998

2001

2004

2007

2010

2013

GCC

Sou rce: Ding, Xiao dan an d Metodij Hadzi-Vaskov, 2017, "Composition of Trade in Latin America and the Cari bbean, " IMF W ork ing Pap er

No. 17/42 (Washington: International Monetary Fund).

1/ This chart shows the distribution of exports for different regions according to the level of product complexity: top area corre

sponds to

the share of exports that belong to the top (fifth) quintile in terms of product complexity index (PCI), and the bottom area corresponds

to the share of products int he bottom quintile of the distribution of the produc complexity index (PCI).

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

10 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Trade in services

14. Services play an increasingly

important role in the GCC’s trade. The

share of service exports has increased

from around 5 percent of non-oil GDP in

2000 to 12 percent in 2017, while the

share of service imports has increased at a

slower pace, from 20 to 23 percent of

non-oil GDP, during the same period

(Figure 7).

15. Tourism and transportation

services make the bulk of the GCC’s

trade in services. Tourism remains one of the region’s fastest-growing sectors. In 2016, the

GCC’s exports of tourism were approximately half of total services exported. The UAE and Saudi

Arabia account for more than 75 percent of travel receipts, given their leading positions as

leisure and religious tourism destinations, respectively. Transportation is the second largest

traded service in the region with a share of 35 percent. A similar pattern holds for GCC imports of

services—travel dominates services imports followed by transportation (Figure 8).

Figure 8. GCC: Trade in Services by Type

Foreign Direct Investment

16. FDI inflows have weakened in recent years (Figure 9). While reforms have been

implemented to attract foreign investment, these have taken place against the backdrop of the

lingering effect of the global financial crisis and rising uncertainties and geopolitical tensions in

the Middle East region. Even though the GCC countries are capital-rich, attracting FDI can bring

access to foreign markets, better management practices and technical know-how to the

domestic economy, thus enhancing work force skills and increasing productivity (World Bank,

2013).

Figure 7. GCC: Trade in Services, 2000–17

(In percent of non-oil GDP)

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

GCC BHR KWT OMN QAT SAU UAE

Transportation Tra vel Other

GCC Exports of Services

(In percent of total, latest data available)

Sources: UN Comtrade; and IMF staff calculations.

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

100%

GCC BHR KWT OMN QAT SAU UAE

Transportation Tra vel Other

GCC Imports of Services

(In percent of total, latest data available)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

Exports

Impo rts

Sources: W orld Economic O utlook; and IMF staff calculations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 11

Figure 9. GCC: FDI Flows

17. FDI inflows into the region have been skewed toward specific sectors and

concentrated in two GCC countries. FDI inflows have largely financed green field investments

with 60 percent of the inflows concentrated in three sectors — real estate, petroleum, and

chemicals (Figure 10). Reflecting their size, Saudi Arabia and the UAE have attracted almost

80 percent of total FDI inflows.

18. While the sources of FDI are diversified in terms of geography, a few countries

account for most of it. The US and India have been the origin of more than a quarter of FDI

inflows in recent years, while the UAE represents a sizable portion of FDI inflows into other GCC

countries (Figure 11). During 2003–16, intra-GCC FDI flows have been concentrated in the real

estate, hydrocarbon and tourism sectors.

Figure 10. GCC: Foreign Direct Investment

Petroleum

16.7

Chemicals

18.3

Real estate

25.0

Tou rism 9.7

Other 30.3

GCC: Cumulative FDI Flows by Sector, 2012-2016

(Percent of total)

Sou rce: Arab Investment and Export Credit Guarantee

Corporation, 2017; and IMF staff calculations.

Other

36.5

UAE 14.3

USA 15.0

India 11.6

UK6.5

France 6.1

Sin g apo re 4.0

China 3.4

Saudi Arabia2.7

Sou rce: Arab Investment and Export Credit Guarantee

Corporation, 2017; and IMF staff calculations.

GCC: Cumulative FDI Flows by Source, 2012-2016

(Percent of total)

0

10

20

30

40

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

EMDCs

AE GCC

FDI Inflows, 2000-17

(In percent of GDP)

Sources: Country authorities; and IMF staff

calculations.

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

FDI Inflows

FDI Outflows

Ne t FDI flo ws

GCC FDI Flows, 2000-17

(In USD billion)

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

12 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

C. Foreign Trade and Investment Environment

The GCC countries have made strides in improving the foreign trade and investment environment

including through regional integration and harmonization. While geopolitical tensions and global

weakening of FDI flows to emerging markets are creating headwinds, further reducing non-tariff

barriers and regulatory restrictions on FDI would help boost trade and foreign investment.

19. There is substantial scope to increase non-oil exports and boost FDI inflows. While

trade openness is relatively high, the value-added and diversification of exports remain relatively

low; likewise, FDI inflows to the region have underperformed other emerging markets and

remain concentrated in a few sectors. This section examines policy and institutional frameworks

that might have contributed to these outcomes.

Current State of Regional Collaborative Arrangements

20. Founded in 1981, the GCC has provided the basis to promote economic cooperation

and integration within the region. Over the course of almost three decades, it has gradually

evolved into an increasingly integrated economic bloc with harmonized legal and economic

systems and coordinated external commercial policies and trade relations (Figure 11). The

founding of the GCC Customs Union in 2003 was meant to encourage free trade, and the GCC

common market in 2008 was a step further to promote cross-national labor and capital mobility.

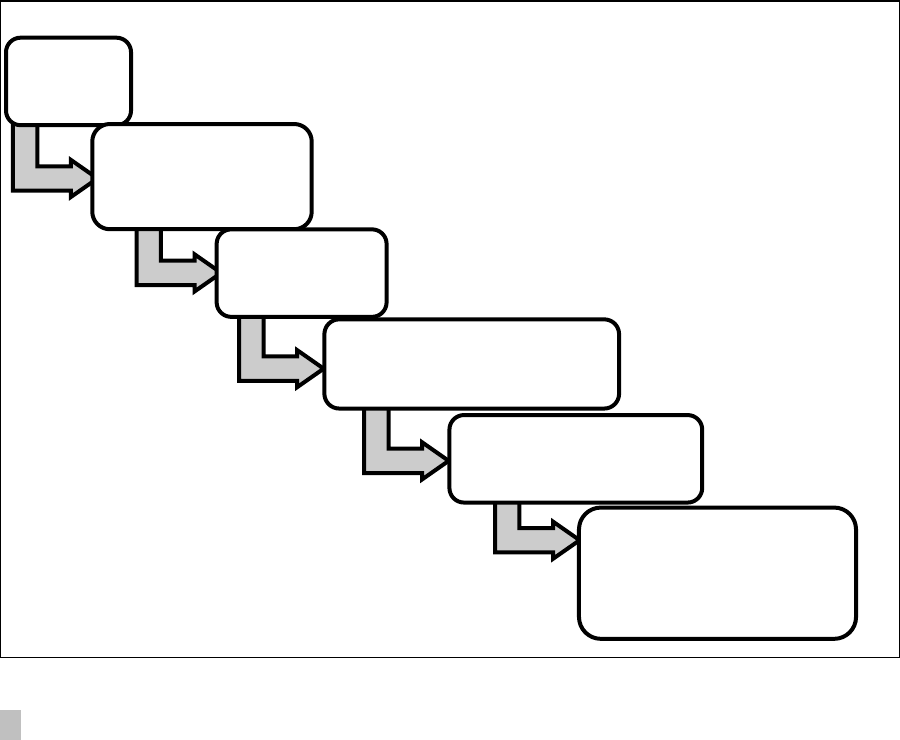

Figure 11. Evolution of the GCC Supra-National Trade and Investment Policies

1981

GCC

established

1983

exemptions of most domestic

products from customs duties

simplified customs and travel

procedures among GCC states

1990

retail and wholesale

trade opened to any

GCC national

2003

Customs Union Agreement

removal of restrictions on internal trade

establishing common external tariffs

2008

GCC Common Market

labor market mobility

unrestricted rights of ownership and

property, capital mobility

similar tax treatment

2005

Agreement to coordinate all

external trade negotiations through

the GCC Secretariat

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 13

21. All GCC countries are members of the WTO and are part of other regional

agreements. Saudi Arabia was the last GCC member to join the WTO in 2005. The GCC countries

are active members of Pan-Arab Free Trade Area (PAFTA), which was established in 1997 under

the auspices of the Arab League. Furthermore, a number of bilateral and collective free trade

agreements are in force and several more are being negotiated. In 2008, the GCC signed a free

trade agreement with Singapore, which went into effect in 2013. All GCC countries have

preferential trade agreements with Kazakhstan, Russia, Turkey, and Australia. In addition, Bahrain,

Oman, and Saudi Arabia have bilateral agreements with a number of other countries. In 2005, the

GCC countries agreed to coordinate all external trade negotiations through the GCC Secretariat.

In general, collective trade agreements in the GCC have advanced very slowly, partly reflecting

difficulty of adhering to common interests.

Trade and Investment Policy Indicators and Impediments

22. Intra-regional trade barriers are very low, apart from those related to the

diplomatic rift last year. As of June 2017, tariff barriers were non-existent and nontariff trade

barriers between GCC countries had been progressively lowered. GCC nationals could freely

participate in business activities related to retail and wholesale trade, recruitment offices, car

rental, and most cultural activities. Restrictions on stock ownership and property possession by

GCC citizens had also been reduced. The GCC countries had adopted unified GCC technical

standards, and harmonized and reduced customs administrative procedures and clearance

requirements. The remaining indirect trade barriers included preferential policies and practices

related to public procurement, subsidies to domestic producers, and customs border controls.

23. The GCC’s external tariffs are relatively low (Figure 12). The Customs Union

Agreement, signed in 2003, established a common GCC external tariff of 5 percent on most

imported merchandise and of zero percent on essential goods (roughly a fifth of total imports).

The average Most Favored Nation applied tariff rate dropped from 8.2 percent in 2000–04 to

5.9 percent in 2006–09 and to about 4 percent in 2016.

24. Prevalence of non-tariff barriers varies widely within the GCC region (Figure 12 and

Table 1). According to the World Economic Forum’s (WEF) 2017 Global Competitiveness Index,

the UAE ranks among the least restrictive countries in terms of non-tariff trade barriers, while

Kuwait ranks among the most restrictive. Likewise, the OECD’s Trade Facilitation Indicators

Database ranks the UAE as a top performer in trade facilitation. The WEF’s Global Enabling

Trade Report, which ranks 136 countries in terms of market access, border administration,

infrastructure, and operating environment, points to a wide heterogeneity among GCC countries

in creating an enabling environment for trade: the UAE ranks in the top 25

th

percentile across

most dimensions and Kuwait ranks in the bottom 25

th

percentile (Table 1). Some constraints are

common throughout the GCC—time and cost (both documentary and border compliance) to

import and export.

4

GCC countries are reviewing their regulations with a view to ease them.

4

These indices are based on WEF’s and OECD’s quantitative and qualitative assessment of the trade and

investment environment and should be interpreted with caution due to a limited number of respondents, limited

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

14 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

Figure 12. Direct and Indirect Trade and FDI Barriers 1/

Sources: WEF Global Competitiveness Index; OECD Stat; IMF AREARER

Report; and IMF staff estimates.

1/ Indices on the prevalence of trade barriers ranking and regulatory restrictions on FDI and their subcomponents are based on WEF’s and OECD’s

quantitative and qualitative assessment of the trade environment. These indicators should be interpreted with caution due to a limited number of

respondents, a limited geographical coverage, and standardized assumptions on business constraints, and information availability.

geographical coverage, and standardized assumptions on business constraints, and information availability. They

may also not reflect more recent important structural transformations that are ongoing in the GCC countries.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

Bahrain Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi

Arabia

United

Arab

Em irates

GCC: Capital Account Restrictions, 2015

(Higher number indicates more restrictions)

AE Average

0

0.01

0.02

0.03

0.04

0.05

0.06

0.07

0.08

0.09

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

Kazakhstan

South Africa

UK

OECD - Avg.

Chile

Egypt

Turkey

Morocco

Mexico

United States

Canad a

Norway

Viet Na m

Russia

India

Malaysia

China

Tunisia

Saudi Arabia

Indonesia

Philippines

restrictions on foreign equity

restrictions on key foreign personnel (RHS)

Restrictions on Foreign Equity and Key Personnel, 2017

(subcomponents of FDI Restrictiveness Index; 0=open, 1=closed)

0

0.05

0.1

0.15

0.2

0.25

0.3

0.35

0.4

0.45

0.5

Argentin a

UK

Sou th Africa

Chil e

Turkey

OEC D - Avg .

Egy pt

Morocco

Mo ngoli a

Peru

Nor wa y

United States

Br az il

Kazakhstan

Ukrain e

Viet N am

Canada

Tuni sia

Russia

Mex ico

In di a

Jo rd an

Malaysia

Chin a

In do nesia

Saudi Ar ab ia

Ph ilippines

2017

2007

FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index

(0=open, 1=closed)

BHR

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

ARE

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

0 5 10 15 20

Prevalence of Trade Barriers (Rank)

Trade Tariffs (Trad e-weighted average tariff rate)

Trade Restrictions, 2017

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 15

Table 1. Enabling Trade Index and Subcomponents, 2016 1/

(Highest performing and lowest performing 25

th

percentiles are marked in green and red, respectively)

Sources: World Economic Forum, The Global Enabling Trade Report, 2016; and IMF staff calculations.

1/ The World’s Economic Forum’s “Enabling Trade Index” assesses the extent to which 136 countries have in place institutions, policies,

infrastructures, and services facilitating the flow of goods over border and to their destination. These indicators should be interpreted

with caution due to a limited number of respondents, a limited geographical coverage, and standardized assumptions on business

constraints, and information availability. They may also not reflect more recent important structural transformations.

25. Unified technical standards, harmonized customs administration procedures and

reduced clearance requirements have lowered non-tariff barriers within the GCC. There

are a number of special agencies in charge of creating and implementing technical standards,

undertaking commercial arbitration, and registering patents: the Standardization and Metrology

Organization for GCC in Saudi Arabia, the Technical Telecommunications Bureau in Bahrain, and

the Regional Committee for Electrical Energy Systems in Qatar.

Bahrain

Kuwait Oman

Qatar

Saudi Arabia UAE

Overall rank (out of 136): 42

115 46 43

67 23

Domestic market access: 59 66

25

71 81

70

Tariff rate (%)

4 4 4 4 4 4

Tariff rate ranking 52

54

60 55

58 56

Share of duty free imports (%) 42 39 60 34 27 36

Foreign market access:

109 132

118

134 125

131

Tariff rate faced (%) 5

5

5 5

5 5

Tariff rate ranking

116 125 118 126 131 129

Border administration ranking:

58 90

48

46 83

25

Customs services index 56 64 77 87 63 2

Efficiency in clearance process

41 56 62 21 69 12

Time to import (documentary) 101

107 63 89

112 58

Time to import (border compliance) 72 123 81

99 126 72

Cost to import (documentary)

81 114 31

129 119

111

Cost to import (border compliance) 80

108 69 119

121 116

Time to export (documentary)

68 81 67 57

113 51

Time to export (border compliance) 99 101 83

60 96 58

Cost to export (documentary)

113 109 85 96

82 104

Cost to export (border compliance)

18 118 54

90

59 102

Irregular payments and bribes 26

77 37 12 32

6

Time predictability of import procedures 36 107

52 22

58 6

Customs transparency index 109 66

39 66 96 66

Infrastructure ranking: 34 56 41 23

36 6

Availability and quality of transport

infrastructure

40 71 32 25 31 2

Availability and quality of transport services

36 65 50 24 47

13

Availability and use of ICTs 22 42 54 29

40 19

Operating environment ranking: 23 68 30 10

39

9

Protection of property 30

76 31 19 32 22

Efficiency and accountability of government

23 71 33 11 29

2

Access to finance 23 46 33 8 44 17

Openness to foreign participation 13 123 89

52 117

30

Physical security 52

47 6 10 57 2

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

16 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

26. Over the past decade, GCC governments have made strides in opening their

countries to FDI, but some restrictions persist. All GCC countries have implemented reforms

to reduce red-tape and administrative burdens placed on domestic and foreign firms and actively

promoted abroad their image as an attractive business destination. Some (e.g., the UAE) have

also created special economic zones (SEZs) with independent, liberalized regulations and

well-established infrastructure. However, openness to foreign entry (outside the special

economic zones) varies widely among the GCC members, with the UAE and Bahrain being the

most liberal and Kuwait and Saudi Arabia the most restrictive.

5

Strict restrictions on foreign

ownership of land may also act as a potential impediment to FDI: such ownership is strictly

limited to zones designated by the government (Bahrain), tourist areas (Oman) or areas for

housing purposes (Qatar). Non-GCC citizens may not own land in Kuwait. While external forces,

such as geopolitical tensions and the slowdown in global FDI flows since the global financial

crisis, create headwinds, relaxing these restrictions would help reinvigorate FDI inflows.

27. The GCC governments offer a variety of incentives to attract FDI. These include:

assistance with registering and opening businesses, financial incentives, exemptions from import

duties on raw materials and equipment, and duty-free access to other GCC markets. In Kuwait,

the government has established a unit to streamline registration and licensing procedures for

foreign investors with a goal of approving licenses in 30 days. The new FDI law in Kuwait allows

for tax benefits, customs duties relief, land and real estate allocations, and permission to recruit

required foreign labor. Oman’s FDI incentives include a five-year renewable tax holiday,

subsidized plant facilities and utilities, custom duties relief on equipment and raw materials for

the first ten years.

28. While SEZs are increasingly being used in the GCC to facilitate trade and FDI, they

should be considered as part of a country’s long-term reform agenda. The UAE has

established more than 20 SEZs, where foreigners may own up to 100 percent of the equity in an

enterprise, have 100 percent import and export tax exemption and repatriate 100 percent of

capital and profits. Kuwait established a free trade zone at Shuwaikh port in 1999, which allows

for 100 percent foreign ownership and tax exemptions, and is in the process of creating two new

zones. Khalifa bin Salman Port in Bahrain has a free transit zone to facilitate the duty-free import

of equipment and machinery and has set up an international investment park that gives foreign-

owned firms the same investment opportunities as Bahraini companies. Oman has also

established three free-trade zones at strategically located ports. Saudi Arabia has announced

plans to build new economic cities. However, it bears noting that the ultimate benefits of SEZs

depend on the extent to which they are integrated with the local economy. While SEZs can

attract FDI by offering better infrastructure and regulatory environment, they should not be

viewed as the end goal, but rather as a second-best and temporary solution before more

business-friendly regulatory framework and practices are extended throughout the country.

5

In 2016, Bahrain relaxed its foreign ownership restriction to allow full foreign ownership of business except for a

few sectors, and the UAE recently announced major relaxation of foreign ownership restrictions.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 17

Indirect trade and investment barriers

29. Rules and regulations on trade and FDI do not fully capture a country’s trade and

investment climate. Inconsistent interpretation and arbitrary application of rules may

complicate business decisions, create opportunities for corruption and gate-keeping, and, along

with public sector dominance, act as an impediment for trade and FDI. As shown in Section IV,

countries with a better business climate and investor protection tend to perform better in

realizing their export and FDI inflows potential. A conducive trade and investment climate

requires certainty that investments are protected from expropriation, that all investors (foreign

and domestic) will be given fair and equitable treatment, that the rule of law is enforced, and that

dispute settlement mechanisms and good corporate governance practices are in place.

Additionally, adequate infrastructure and a well-educated and trained workforce play a

significant role (Box 1 discusses Singapore’s success story of becoming a top FDI destination).

Governance and legal regime

30. The GCC region has made important progress in improving governance, but further

reforms are needed. Promising reforms have been implemented and more are on the way,

aimed at strengthening the rule of law, building effective safeguards against corruption, and

improving transparency in government decision making. In Bahrain, a law to completely revamp

government procurement procedures went into effect in 2003, and mandates criminal penalties

(up to 10 years imprisonment) for official corruption. In Saudi Arabia, a high-level anti-corruption

committee was established in 2017, the new public procurement law is nearing completion, and

a “whistleblower” protection framework is being put in place. In Kuwait, corruption is criminalized

with several investigations and trials involving current and former public officials underway and

the Anti-Corruption Agency is developing a national strategy for anti-corruption efforts. Still,

issues persist in the context of public administration, including in public procurement, business

licensing, and revenue administration (see IMF, 2017c; d).

31. Another important aspect of the business environment is whether corporate

governance standards and practices are adequate to assure potential investors. Weak

corporate governance can discourage international investors from investing: this is an area where

the GCC economies seem to have a substantial room for improvement. For example, potential

investors in the region often face a lack of an independent board, insufficient oversight and

scrutiny of key enterprise risks, and weak transparency and disclosure practices (S&P Global,

2017). Important reforms have recently been enacted in this area in Saudi Arabia.

32. The GCC countries have signed several investment treaties that ensure protection

for foreign investors. These treaties provide benefits and protection to foreign investors, such

as the most-favored nation treatment and national treatment, the right to make financial

transfers freely and without delay, international law standards for expropriation and

compensation, and access to international arbitration. However, legal ambiguity in the GCC

legislation can give rise to too much regulatory discretion, thereby affecting trade and

investment even if there is no explicit discrimination against foreign firms (Heuser and Mattoo,

2017).

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

18 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

33. The GCC states have used international and regional conventions to enhance their

commercial arbitration legal frameworks, though the legal systems lag in operational

efficiency. The courts are perceived as slow and inefficient. Entrenched local business interests

with government influence can cause potential problems for foreign companies (see the 2017

EU-Gulf Cooperation Council Investment Report). The full potential of arbitration and mediation

mechanisms, which could have reduced the case load of the courts, is not utilized. Despite having

a regional GCC Commercial Arbitration Center, which is empowered to implement rules and

Box 1. Tapping Greater FDI Inflows: The Case of Singapore

Singapore’s FDI Inflows, 1995–2017

(Percent of GDP)

Singapore has been one of the most attractive

destinations for foreign direct investment. As of

end-2016, its gross FDI stock was almost three

times its GDP. Despite blips during regional

and global financial crises, its already-high FDI

inflows have continued to increase as a share

of GDP over the last two decades.

Singapore’s success in continuing to attract FDI

lies in its business-friendly environment, strong

legal and political institutions, world-class

infrastructure, and highly skilled labor force. It

has been consistently ranked near the top by

the World Bank’s “Doing Business” reports

(2

nd

in 2018), the World Economic Forum’s

“Global Competitiveness Report” (3rd in

2017-2018), and the OECD’s PISA global

education survey (1st in the latest, 2015

survey).

Composition of Singapore’s FDI Stock

Like the rest of the world, Singapore uses FDI

incentive policies, but its strategy has switched

from targeting the overall volume of FDI

inflows to target FDI in specific sectors to

maximize the impact on growth and

development. In the 1960s, it began with tax

incentives to attract FDI. By the late 1970s to

1990s, its focus shifted to promote higher-

value added production activities and to

further upgrade the labor force skills. And

starting in 2000s, the emphasis has shifted to

knowledge-based industries, including

innovation, research and development, for

example in pharmaceuticals and

biotechnology. As a result, the FDI stock in

manufacturing has declined from 41 percent of

the total FDI stock in 1990 to just 13 percent in

2016.

In recent years, responsible investment has become an important policy consideration. In addition to the

enactment of Environment Protection and Management Act, Singapore has also included labor rights and

environmental protection terms in various bilateral agreements on trade and investment.

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

FDI inflow/GDP

Linear (F DI inflow/GDP )

Sources: Country authorities; and World Economic Outlook.

48%

23%

13%

8%

3%

4%

2%

2016

Financial & Insurance Services

Wholesale & Retail Trade

Manufacturing

Professional, Scientific & Technical, Administrative & Support Services

Real estate & Construction

Information & Communications & Transport & Storage

Others

34%

12%

41%

2%

6%

3%

1%

1990

Sou rces: Singapore Department of Statistics; and IMF staff calculations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 19

regulations in line with accepted international practice, very few cases have been brought to

arbitration so far. Furthermore, in Kuwait, nationals and foreigners who are involved in

unresolved financial disputes with local business partners can be subject to travel bans. As a

positive development, Saudi Arabia introduced specialized commercial courts in three major

cities in 2017, with the aim of expediting dispute resolution and boosting investor confidence.

34. The GCC countries lack comprehensive competition protection mechanisms.

6

While

all GCC countries have passed specific competition laws, these often do not apply to the

government or entities controlled by the government, and the enforcement mechanism is weak

(Daudpota, 2015). The Saudi Competition Protection Council is the most advanced in terms of

monitoring anti-competitive conduct; however, the law exempts public corporations and wholly-

owned state companies, and even commercial operators dealing with state-owned companies,

from the competition rules. Qatar’s law also grants exemptions to sovereign ventures and to all

entities subject to State direction and supervision. Bahrain has neither a formal competition law

nor a specialized agency to monitor competition-related issues. Kuwait has established a

Competition Protection Bureau intended to safeguard free commerce, bar monopolies, and

supervise mergers and acquisitions, but it is not yet fully operational. Oman has passed the

Competition and Anti-Monopoly Law, but

only recently established a competition

protection agency (Casoria, 2017).

Public sector dominance

35. The size of the public sector in the

GCC economies constitutes an important

impediment to private domestic and

foreign investment. The most important

economic sectors like oil and gas production,

electricity, transport and, to some extent,

telecoms are still dominated by state-owned

companies and are protected from foreign

competition. Due to the size of the public

sector, preferential treatment given to

domestic enterprises engaged in government

procurement creates an uneven playing field

and acts as a disincentive for FDI.

7

Furthermore, public procurement practices,

which substantially lag those in advanced

economies (Figure 13), may encourage low-

6

Casoria (2017) finds that notwithstanding the wide arsenal of legal tools to curb possible anticompetitive

practices, in all GCC countries, the application of competition laws and role and powers of the competition

authorities (if they exist) is still at a rudimentary stage of development.

7

The GCC states are not signatories to the WTO Government Procurement Code.

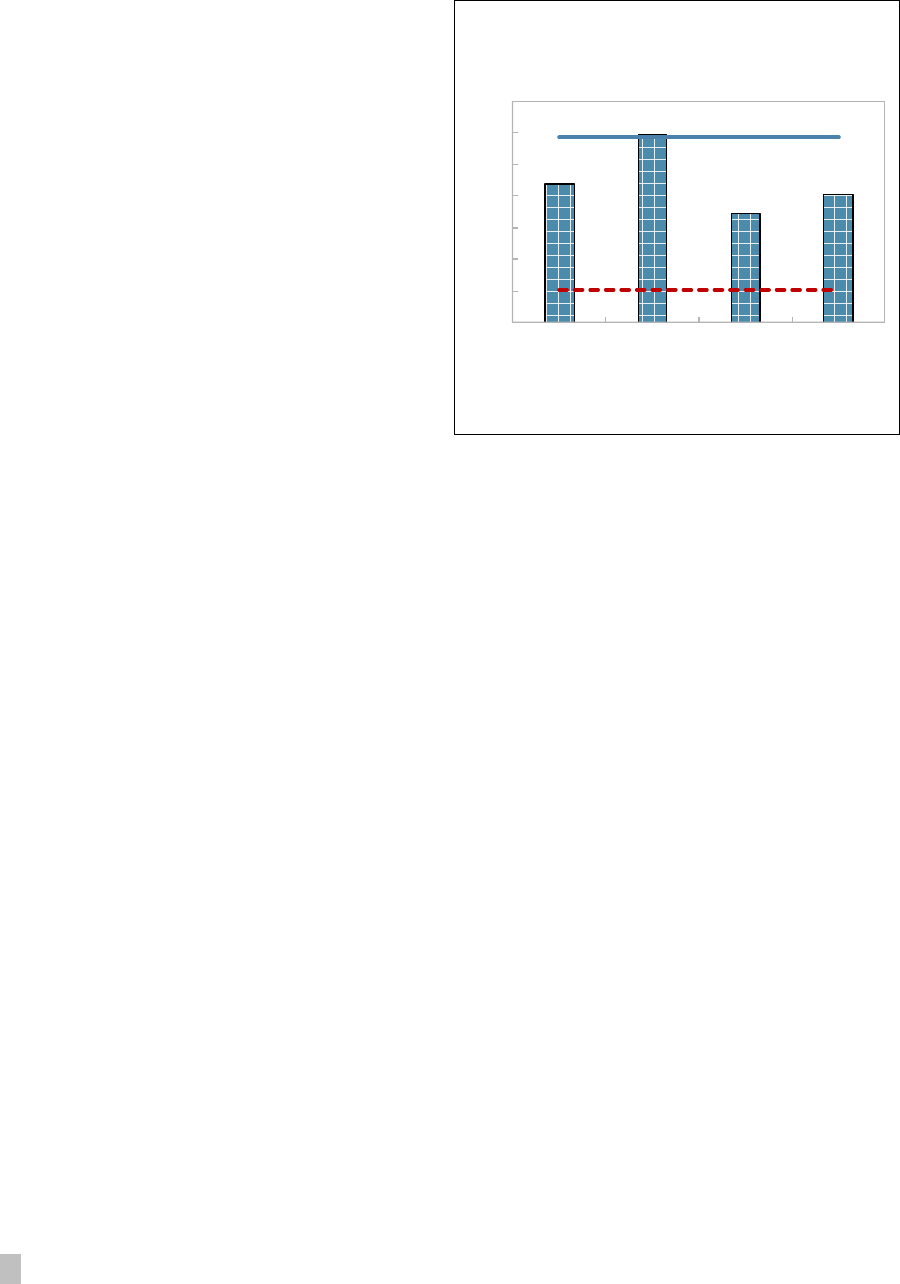

Figure 13. GCC: Average Public

Procurement Indicators, 2017 1/ 2/

(Higher score indicates better

public procurement)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Qatar Kuwait Saudi

Arabia

UAE Oman Bahrain

AE Average

EM Average

Sources: World Bank Benchmarking Public Procurement,

2017.

1/ Score is an average of 6 indicators where points are

assessed based on responses to questionnaires.

2/ The World Bank’s public procurement indicators are

based on primary data collected from surveys administered

to expert contributors in 180 economies. These indicators

should be interpreted with caution due to a limited number

of respondents, a limited geographical coverage, and

standardized assumptions on business constraints, and

information availability. They may also not reflect more

recent important structural transformations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

20 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

efficiency investment in non-tradable sectors and their expansion, thus potentially crowding out

tradeable sector development.

36. Recent reforms aim at reducing the share of SOEs in the economy through

privatization and PPPs. The privatization momentum is picking up in the GCC, with a number of

SOEs earmarked for privatization.

8

However, this process remains particularly complicated, due to

the long history of strong state intervention in many industries and the implicitly assumed

responsibility of the state as the employer of first resort for nationals. Furthermore, business

interests in industries that are slated for privatization may likewise try to slow down the

privatization process and opening of certain sectors to FDI.

Infrastructure and labor market

37. Most GCC countries do relatively well

in logistics performance. The World Bank’s

Logistics Performance Index (LPI)—the

weighted average of a country’s scores on six

dimensions: customs, infrastructure,

international shipments, logistics competence,

tracking and tracing, and timeliness—suggests

that Qatar and the UAE perform at or above

high-income countries’ average, while Kuwait

lags behind other GCC countries (Figure 14). As

shown in Section IV, the level of infrastructure

development matters for export diversification

and sophistication.

38. The availability of a well-educated

and skilled workforce matters for trade

diversification and FDI. As the empirical analysis in Section IV shows, human capital is a key

determinant of export performance and FDI. Faced with pressures to accommodate new entrants

into the workforce amid restricted public-sector employment, many GCC governments have

tightened regulations for hiring of foreign nationals. The regulations are especially binding for

higher-skilled jobs. This may impose constraints on potential FDI, dampen efficiency and

competitiveness, and slow down economic diversification efforts.

8

In 2016, Kuwait announced that nearly 60 percent of public sector companies are earmarked for privatization

and allowed the private sector to acquire shares of up to $9 billion in public sector firms, such as Kuwait

Petroleum Corporation. The UAE announced plans for privatization of much of the UAE services and Oman

declared that many state-owned energy companies are slated for privatization. Saudi Arabia published a

privatization program in 2018 and has issued a draft private sector participation law for public comment.

Figure 14. GCC: Logistics Performance

Index, 2018 1/

(1=low to 5=high)

4.0

4.0

3.5

3.5

3.2

3.0

2.9

2.9

2.6

0

1

2

3

4

5

Sing apo re

UAE

High Income

Qatar

Oman

Saudi Arabia

Bahrain

Kuwait

MENAP

Sources: World B ank, W orld Development In dicato rs; an d IMF

staff calculations.

1/ The World Bank’s logistics performance index is based on a

worldwide survey of stakeholders on the ground providing

feedback on the logistics “friendliness of the countries in which

they operate and those with which they trade. These indicators

should be interpreted with caution due to a limited number of

respondents, a limited geographical coverage, and

standardized assumptions on business constraints, and

information availability. They may also not reflect more recent

important structural transformations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 21

D. Growth Impact of Enhanced Foreign Trade and investment

There is substantial potential to boost non-oil exports and FDI in several GCC countries. Analysis

suggests large benefits from raising labor productivity, improving the quality of human capital,

enhancing the business climate, and reducing non-tariff barriers.

Expanding non-oil exports

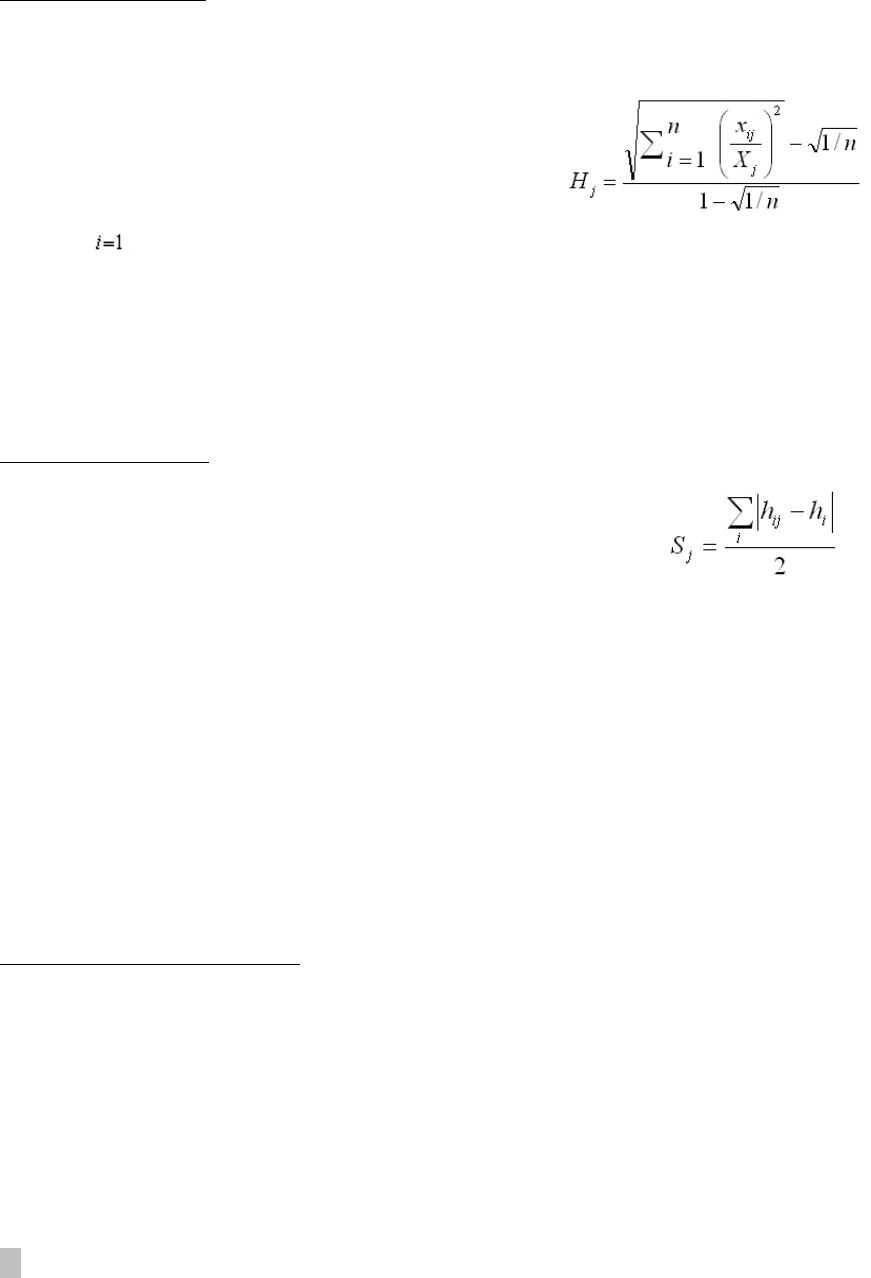

39. The empirical approach focuses first on identifying export determinants in a sample

of non-commodity exporters.

9

Results of this analysis are then used to estimate a “benchmark”

level of non-oil exports for the GCC countries based on the assumption that the sample of non-

commodity exporters provides a reasonable benchmark for what GCC economies could

achieve.

10

A non-oil export gap is then derived. The empirical analysis suggests that country size,

income level, human capital, macroeconomic stability and the real effective exchange rate (REER)

are important determinants of non-oil exports. Trade openness (proxied by average tariffs) is not

found to be a significant determinant of non-oil exports. Similar determinants are found for

export diversification and sophistication; additionally, the level of infrastructure development

becomes a significant determinant.

40. Analysis shows substantial potential to boost exports in several GCC countries. The

estimated coefficients (Appendix II, Table A1) are used to predict the potential non-oil exports in

the GCC countries given their current fundamentals such as education, non-oil income, and other

factors that affect non-oil exports. Then actual non-oil exports are subtracted from their

estimated potentials to arrive at export gap estimates for each country. Kuwait, Oman and Saudi

Arabia are estimated to have the largest total export gaps, followed by Qatar (Figure 15). Bahrain,

and the UAE, on the other hand, seem to export more non-oil goods and services than implied

by the model, resulting in negative total export gaps. A similar picture emerges when looking at

intra-GCC trade (Box 2). When services exports are excluded, the same four GCC countries

continue to exhibit notable export gaps, while only the UAE still shows a negative export gap.

The emergence of a positive gap for Bahrain in non-oil goods exports suggests that its

overperformance in total non-oil exports can be attributed to services given its relatively large

financial sector with substantial international linkages.

9

Given the policy aim is to boost non-oil exports, the analysis is based on non-commodity exporters. The details

of the estimations and the empirical model are discussed in Appendix II.

10

A regression of non-oil exports on a sample of all countries (commodity and non-commodity exporters) that

includes oil as a determinant suggests that oil exports do have a negative impact on non-oil exports. However,

the re-estimated non-oil export gaps based on this specification are not materially different from those in the

baseline.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

22 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

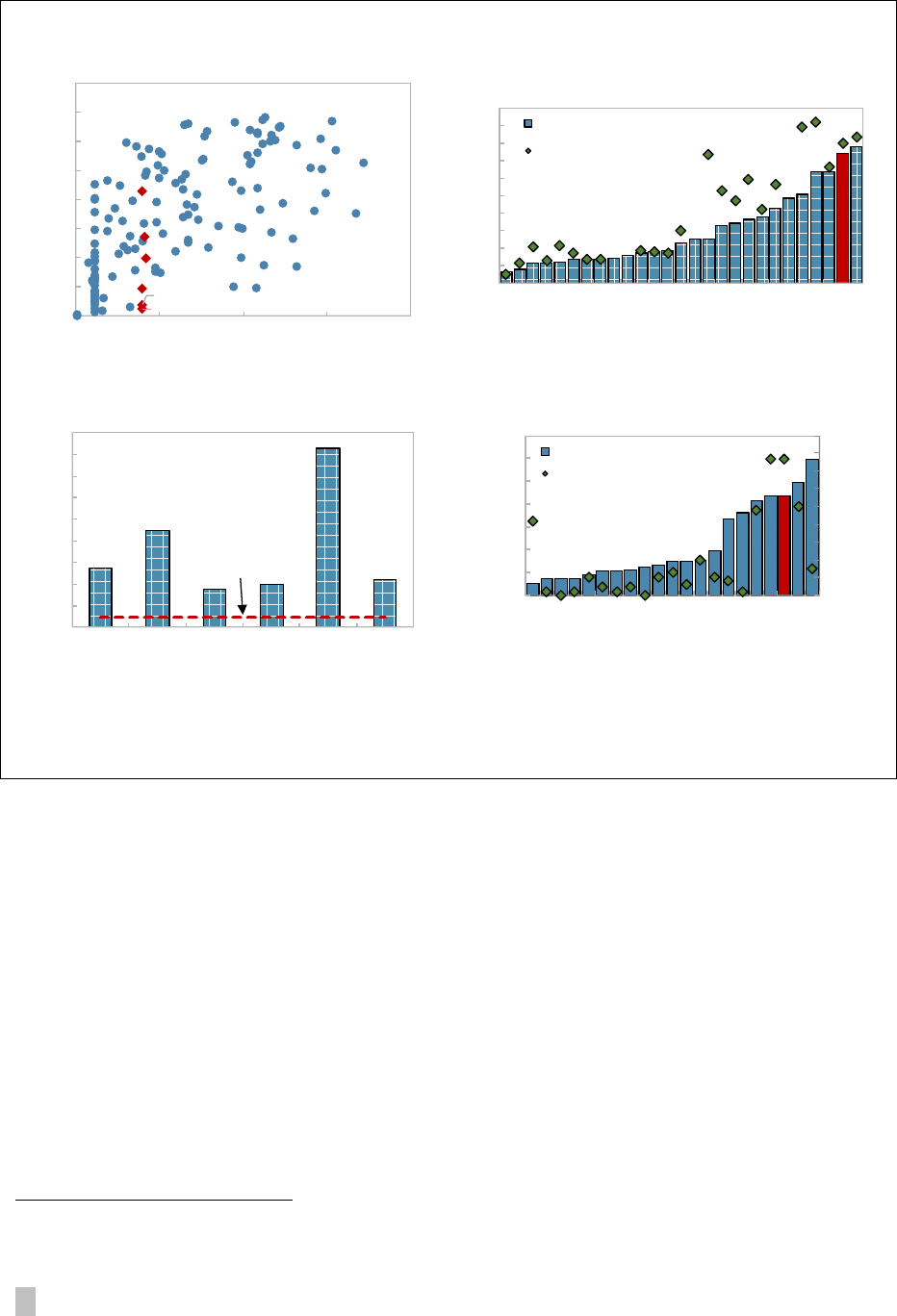

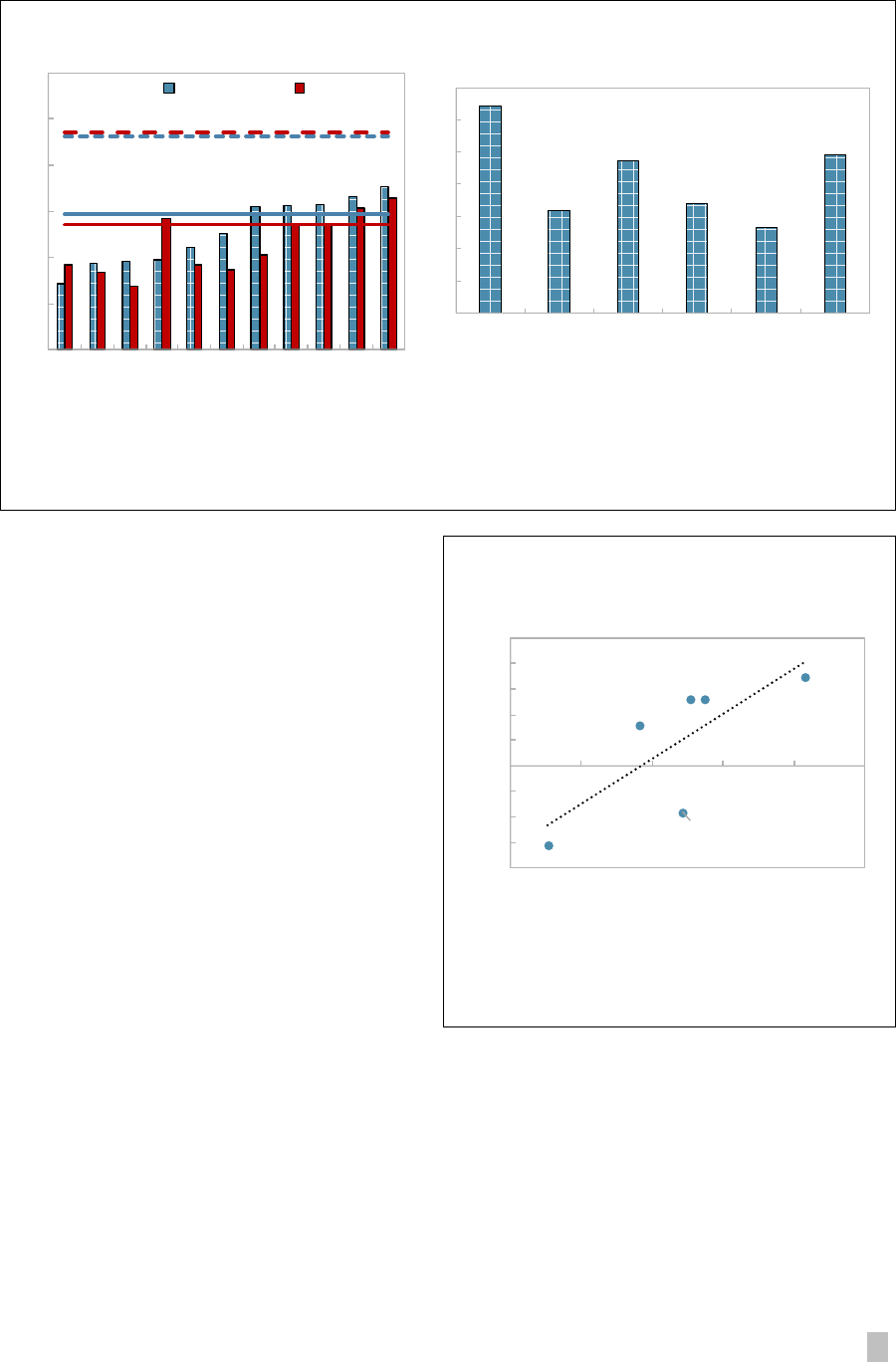

Figure 15. GCC: Potential and Actual Exports

41. A similar methodology points to lower-than-predicted export diversification and

sophistication in some GCC countries. Countries can close their non-oil goods export gaps by

increasing the diversity of export products and destinations and/or climbing up the export

quality ladder by selling goods with higher value-added. In particular, Kuwait, Saudi Arabia,

Qatar, and Oman can benefit from reducing export diversification gaps (Figure 16). These four

countries also have gaps in export sophistication, albeit the gap appears smaller for Oman.

Bahrain’s actual levels of goods export diversification and sophistication are significantly better

than what the fundamentals would suggest. Actual indices for the UAE are at levels predicted by

the model.

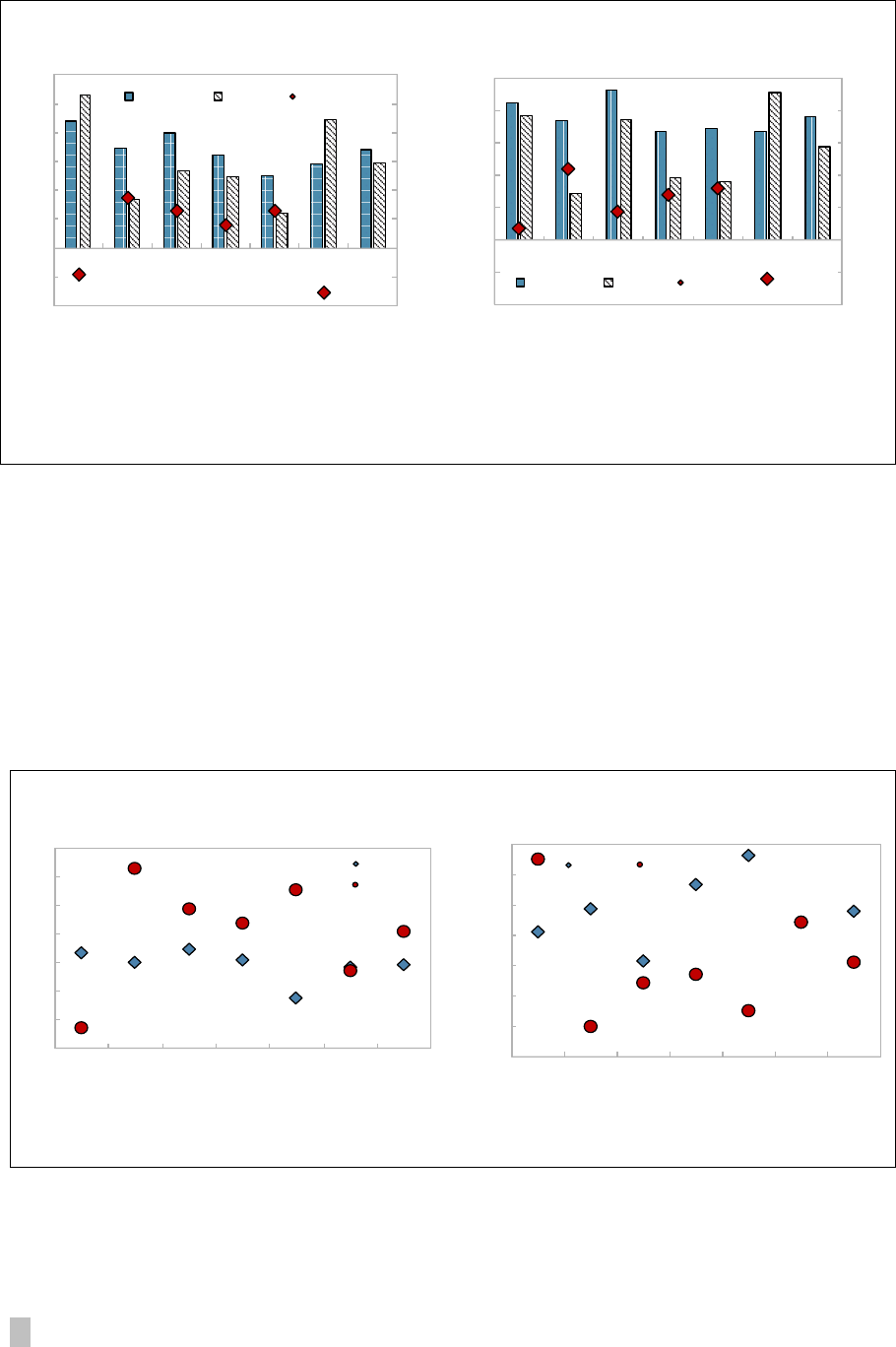

Figure 16. GCC: Export Diversification and Sophistication

2.5

3

3.5

4

4.5

5

5.5

6

Bahrain Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE Simple

average

Export diversification index, 2013 1/

(Lower index=higher diversification)

Potential

Actual

Sources: IMF Staff estimates; and Henn et al., (2013)

1/ The lower index indicates more export diversification.

3500

4000

4500

5000

5500

6000

6500

7000

Bahrain Kuwait

Oman

Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE Simp le

average

Export sophistication index, 2013

(Higher index=more sophistication)

Potential

Actual

Sources: IMF Staff estimates; and Cherif et al., (2018)

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

-20

-10

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

Bahrain

Kuwait Oman

Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE 2/ Simp le

average

Non-oil exports: Potential vs Actual

(Goods and services, as a percent of non-oil GDP)

Potential Actual Gap 1/

So u rces: WEO; and IMF Staff estimates.

1/ Calculated on the basis of th e d iff eren ce between potentia l

and actual levels. The exports are adjusted for re-exports.

2/ The UAE exports are adjusted for precious metals exports due

to their high share both in exports and imports.

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

Bahrain

Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE 2/ Simp le

average

Non-oil goods exports: Potential vs Actual

(Goods, as a percent of non-oil GDP)

Potential Actua l Gap 1/

So u rces: WEO; and IMF Staff estimates.

1/ Calculated on the basis of

th e diff eren ce between potentia l

and actual levels. The exports are adjusted for re-exports.

2/ The UAE exports are adjusted for precious metals exports due

to thier high share both in exports and imports.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 23

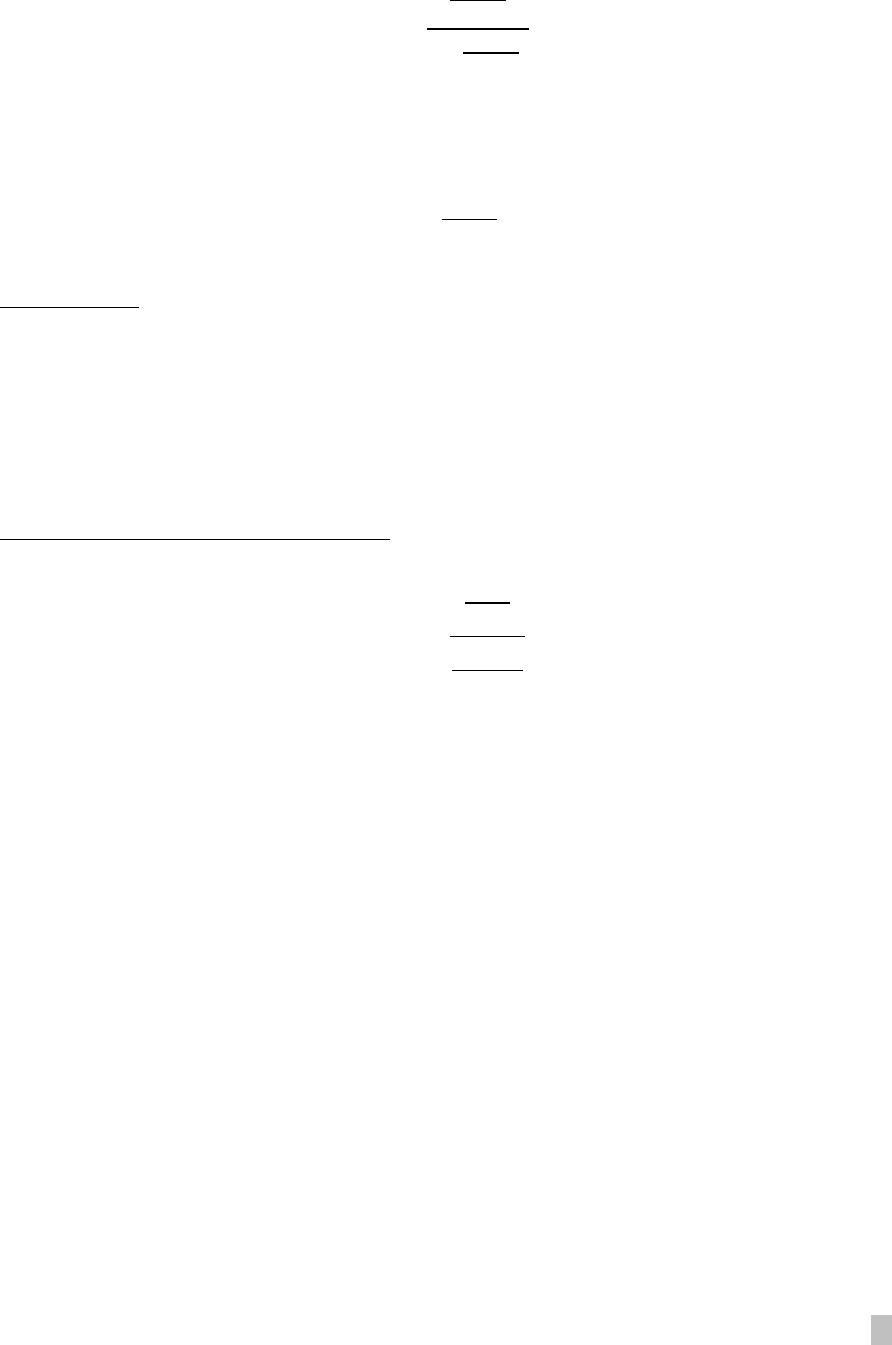

Box 2. Boosting Intra-GCC Non-Oil Trade

There is room to enhance intra-GCC trade.

A gravity model-based analysis suggests

several GCC countries exports to other GCC

members are below their potential.

1

The

largest gap is estimated for Oman, at around 7

percent of non-oil GDP, followed by Kuwait

and Qatar with a gap of around 4 percent

each. Saudi Arabia has a smaller positive gap,

while both Bahrain and the UAE have large

negative gaps. Although Oman’s goods

exports to GCC are non-negligible, a

substantial portion reflects re-exports,

particularly to the UAE, and adjusting for the

re-exports yields a relatively large gap. Closing

the gaps for the four countries can generate

additional exports of about 4 percent of non-

oil GDP on average. Greater regional trade will

also help to close total export gaps to other

parts of the world.

Reducing non-tariff barriers and enhancing

integration into regional and global value

chains are needed to increase the tradable

non-oil sector. Given that low intra-GCC trade

is mostly due to similar economic structures of

the member countries, greater regional trade

can be boosted by diversifying the economy

toward tradables. Eliminating the non-tariff

trade barriers will also help in this regard.

Finally, higher levels of backward integration to

global value chains, characterized by greater

shares of imported foreign value added and

used in the production of exports, can bring

more regional trade into the GCC (IMF, 2017b).

Smaller GCC economies can become integrated

into the supply chains of larger ones, e.g. those

of Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

_______________________

1

See Appendix II Table A3, sub-model (4) for the details

of estimation.

GCC. Intra GCC Non-Oil Goods Exports Gaps,

2015 1/

(Percent of non-oil GDP)

GCC. Trade Barriers and Intra-GCC Export

Gaps, 2015 1/

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

Bahrain

Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE

Source: IMF staff calculations

1/Difference bewteen model predicted and actual values.

Adjusted for re-exports

BHR

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

ARE

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

0 50 100 150

Non-oil export gap (percent of non-oil

GDP)

Prevalence of trade barriers (rank, 1=best)

Sou rces: World Economic Forum; and IMF Staff estimates.

1/ These indicators should be interpreted with caution due to

a limited number of respondents, a limited geographical

coverage, and standardized assumptions on business

constraints, and information availability. They may also not

reflect more recent important structural transformations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

24 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

42. Beyond closing existing exports gaps, GCC countries have significant scope for

boosting non-oil export potential by improving economic fundamentals. The analysis

suggests that the REER and human capital

could be particularly important.

• Based on the traditional relationship

between REER and export performance

(whereby exports rise in response to REER

depreciation), one can argue for more

depreciated REERs in the GCC economies,

especially where the REERs are assessed to

be overvalued. However, given the still-low

degree of economic diversification and the

fact that fixed exchange rate regimes have

delivered monetary policy credibility as

well as low and stable inflation, costs of a

change in the nominal values of GCC

currencies will most likely outweigh the

benefits. Competitiveness gains can instead be achieved by lowering unit labor costs by

increasing productivity and containing relatively high average wages (Figure 17) which are

partly driven by generous public sector compensation (IMF, 2017e).

• The GCC countries, despite having similar or even higher levels of income and spending on

education, appear to lag behind the advanced economies in terms of the education

outcomes, especially in science and mathematics (IMF, 2017e). Improving education quality

in these areas and upgrading workers’ skills could be helpful in transitioning to production

and export of more complex and sophisticated goods and services as well as for raising the

overall productivity of the GCC economies. As an example, GCC’s non-oil exports can be

boosted substantially by raising the quality of education to that of the top 20

th

percentile of

advanced economies: the potential gains would be the largest for Bahrain, at around

6 percent of non-oil GDP, followed by the UAE and Oman (Figure 18). Higher quality human

capital will also work toward expanding job opportunities and making economic growth

more inclusive (IMF, 2018).

Figure 17. Average Monthly Earnings

(US Dollars, latest data available)

0

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

3500

Bahrain 1/ Qatar Saudi Arabia United Arab

Em irates

AE Average

EM

Average

Sources: ILO; and IMF staff estimates.

1/ Data for Bahrain is for nationals only.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 25

Figure 18. GCC: Human Capital

43. The estimated export gaps in the

GCC appear to be related to several factors

identified in Section III. These include public

sector dominance, business climate, and non-

tariff barriers.

• Lower-than-predicted non-oil exports

seem to prevail in a non-tradable,

domestically oriented non-oil economy.

One possible cause for underperformance

for a given size of the non-oil sector could

be the high share of non-tradables in

non-oil GDP, a by-product of public

sector dominance. To this end,

construction, public administration

and health services were defined as non-

tradable (non-exportable) sectors in the

GCC and the results indicate that a relatively large share of non-tradables in the non-oil

economy is associated with identified export gaps (Figure 19).

• Non-tariff trade barriers could be preventing some GCC countries from reaching their

potential. Furthermore, countries with better business climates tend to have smaller total

export gaps. These factors are associated with the estimated export gaps in the GCC

countries (Figure 20).

Figure 19. Non-Tradable Services and

Export Gaps, 2015

(In percent of non-oil GDP)

BHR

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

20 25

30

35 40 45

Non-oil export gap

Share of non-tradable services in non-oil GDP 1/

Source: IMF Staff estimates

1/ Sum of construction, public administration and health, social

and community services. The relationship is broadly unchanged

when health, social and community services are excluded.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Bahrain Kuwait Oman Qatar Saudi

Arabia

UAE

Non-Oil Export Boost from Higher Quality of Education 1/

(Goods and services, percent of non-oil GDP)

Source: WEF; IMF Staff estimates.

1/ Estimates are based on enhancing math test scores to the 80th

percentlie level of AEs. These indicators should be interpreted with

caution due to a limited number of respondents, a limited

geographical coverage, and information availability. They may also

not reflect more recent important structural transformations.

300

350

400

450

500

550

600

EGY

MAR

SAU

LBN

KWT

JOR

OMN

IRN

QAT

BHR

UAE

Science Scores

Math Scores

TIMSS 8th Grade Scores for the Region, 2015 1/

AE Averages

EM Averages

Sources: TIMSS 2015;

and IMF staff calculations.

1/ These indicators should be interpreted with caution due to a

limited n umber of respondents, a limited geographical

coverage, and information availability. They may also not

reflect more recent important structural transformations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

26 INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND

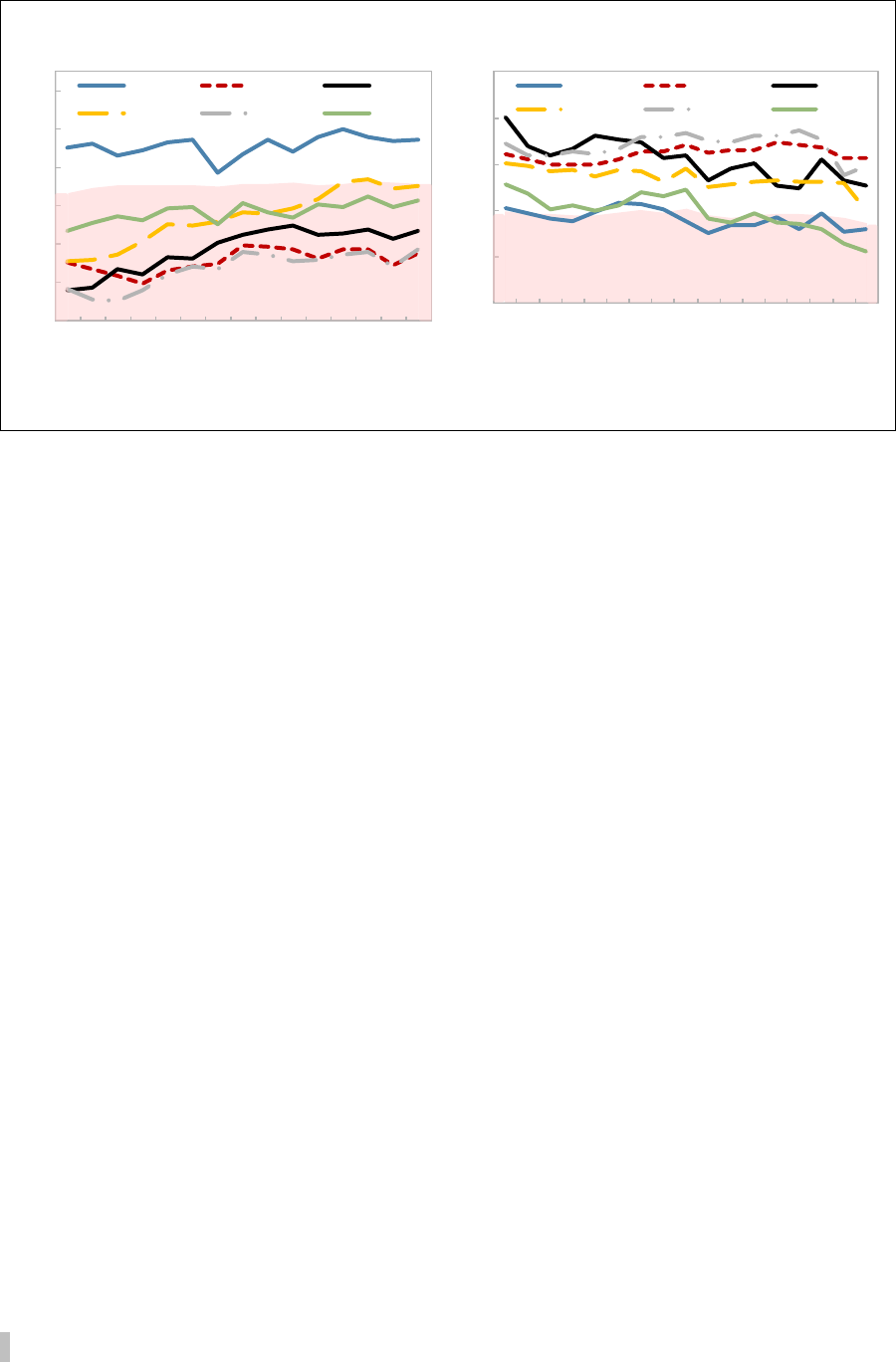

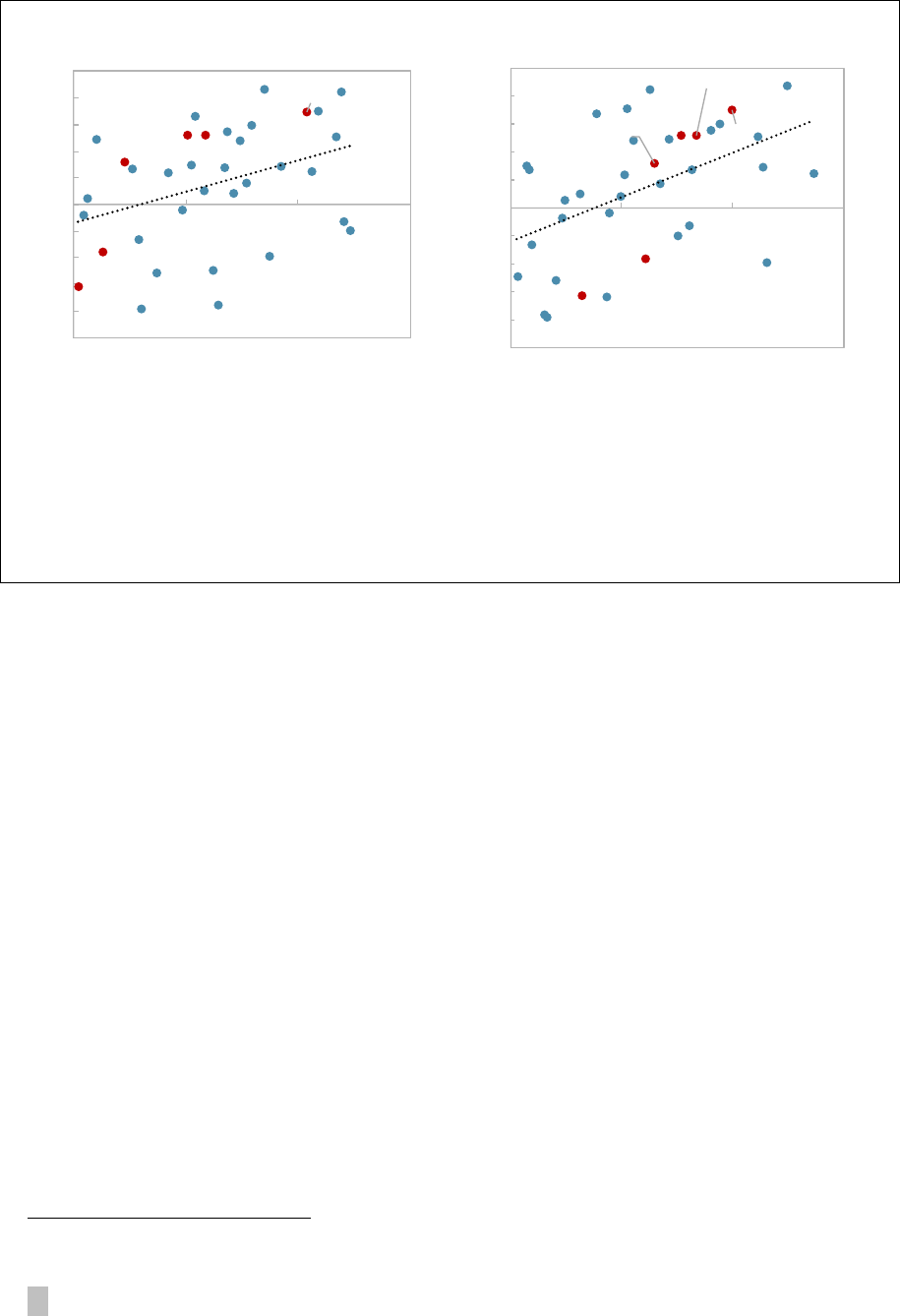

Figure 20. GCC: Trade Barriers and Business Climate

44. Further empirical analysis confirms that additional determinants of non-oil exports

appear to be important for commodity exporters. While non-tariffs barriers and the business

climate were not found to be statistically significant when included in the baseline, a re-

estimation of the baseline regression for commodity exporters found the quality of legal system

(a proxy for business climate) and non-tariff trade barriers to be statistically significant (Appendix

II, Table A2). Additionally, trade openness (proxied by average tariffs) became a statistically

significant determinant of non-oil exports. Thus, in addition to enhancing competitiveness and

human capital, the GCC economies could boost their non-oil exports by improving the quality of

their legal systems and reducing non-tariff barriers to trade.

Attracting more FDI

45. A similar empirical approach is employed to identify FDI inflow potential of the

GCC countries.

11

Trade openness (measured as the share of total exports and imports in GDP),

economic growth, quality of legal systems, and human capital are found to have positive and

significant impact on FDI inflows in the non-commodity exporters group; while capital account

restrictions have the opposite impact. Moreover, having a fixed exchange rate is also found to

have some positive impact on FDI inflows. These estimated coefficients are used to calculate

11

The details of the estimations as well as the empirical model are discussed in Appendix II.

BHR

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

0

50

100 150

Non-oil export gap (percent of non-oil G DP)

Prevalence of trade barriers (rank, 1=best)

Trade barriers and export gaps, 2015 1/ 2/

Sou rces: W orld Economic F orum; and IMF Staff estimates.

1/ Blue dots are non-commodity exporters for which data w as

available.

2/ These indicators should be interpreted with caution due to a

limited n umber of respondents, a limited geographical coverage,

and standardized assumptions on business constraints, and

information availability. They may also not reflect more recent

important structural transformations.

BHR

KWT

OMN

QAT

SAU

UAE

-25

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

20

25

0 50 100 150

Non-oil export gap (percent of non-oil G DP)

Ease of doing business (rank, 1=best)

Business climate and export gaps, 2015 1/ 2/

Sou rces: W orld B ank; and IMF Staff estimates

1/ Blue dots are non-commodity exporters for which data w as

available.

2/ These indicators should be interpreted with caution due to a

limited n umber of respondents, a limited geographical coverage,

and standardized assumptions on business constraints, and

information availability. They may also not reflect more recent

important structural transformations.

TRADE AND FOREIGN INVESTMENT

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND 27

potential FDI among the out-of-sample GCC countries. The estimated FDI potential is then

compared to the actual level to derive FDI gaps.

46. Results suggest the GCC countries could attract more FDI relative to current levels.

On average, the GCC countries are estimated to have the potential to attract additional of

around 2 percent of GDP (Figure 21). Given the high volatility of FDI inflows, the results of the

gap analysis for individual countries are sensitive to the period under examination. For 2016, the

biggest gaps are observed in Bahrain and Qatar, at around 3 percent of their GDP, while the UAE