Setting a new agenda for sustainable

development

The year 2015 has witnessed a signicant

directional shift in the development paradigm.

Member States of the United Nations negotiated

a new development agenda for 2015–2030

applicable to all countries, not only to those of

the developing world. The primary focus is to

achieve development that is sustainable in the

social, economic and environmental spheres.

Many compelling success stories of economic

development in recent decades are based on

trade-led growth. Much of the growth in least

developed countries relies on rising revenues

from commodities. The post-2015 development

agenda and sustainable development goals

suggest that the world should transform its

natural-resource-dependent growth pattern into

one that is “sustained, inclusive and sustainable”.

1

Trade leads to economic development;

trade policy can ensure sustainability

Trade creates employment opportunities,

generates income, reduces costs for industries

and consumers, motivates entrepreneurs and

attracts investment in essential infrastructure.

Trade and economic development can generate

substantial private and public nancial means to

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT

No.

37

pursue the social and environmental dimensions

of sustainable development. Table 1 provides an

illustration of the potential linkages between trade

and sustainable development goals.

Certainly, the development impact of trade is not

unconditional. Firstly, economic development

requires an appropriate sequencing of trade

openness as well as an enabling environment of

other policy and non-policy factors.

Secondly, for economic development to become

inclusive, sustained and sustainable, another

layer of conditions applies. For example, a

positive effect on poverty reduction relies on

favourable sectorial growth patterns and inclusive

employment and social policies. The latter are

important to address potential inequalities within

economies as a result of trade.

In this context, and with falling tariffs, non-tariff

measures have moved to the forefront of trade

policymaking. This policy brief argues that the

proliferation of non-tariff measures plays a crucial

role in shaping global trade patterns and their

sustainability.

Not all non-tariff measures are

non-tariff barriers

Non-tariff measures are dened as policy

measures other than ordinary customs tariffs

SEPTEMBER 2015

POLICY BRIEF

Key points

• Trade leads to economic

development; trade policy can

ensure sustainability

• Many non-tariff measures

are much more than trade

policy instruments

-

they

are sustainable development

policies

• To successfully pursue the

sustainable development

goals, synergies and

trade-offs between means

of implementation must be

exploited

• Some costs of non-tariff

measures can be reduced

without compromising policy

objectives

• Regulatory convergence is

paramount

NON-TARIFF MEASURES AND

SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT GOALS:

DIRECT AND INDIRECT LINKAGES

1 United Nations, 2015, Transforming our world: The 2030 agenda for sustainable development, available at

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld, accessed 14 September 2015.

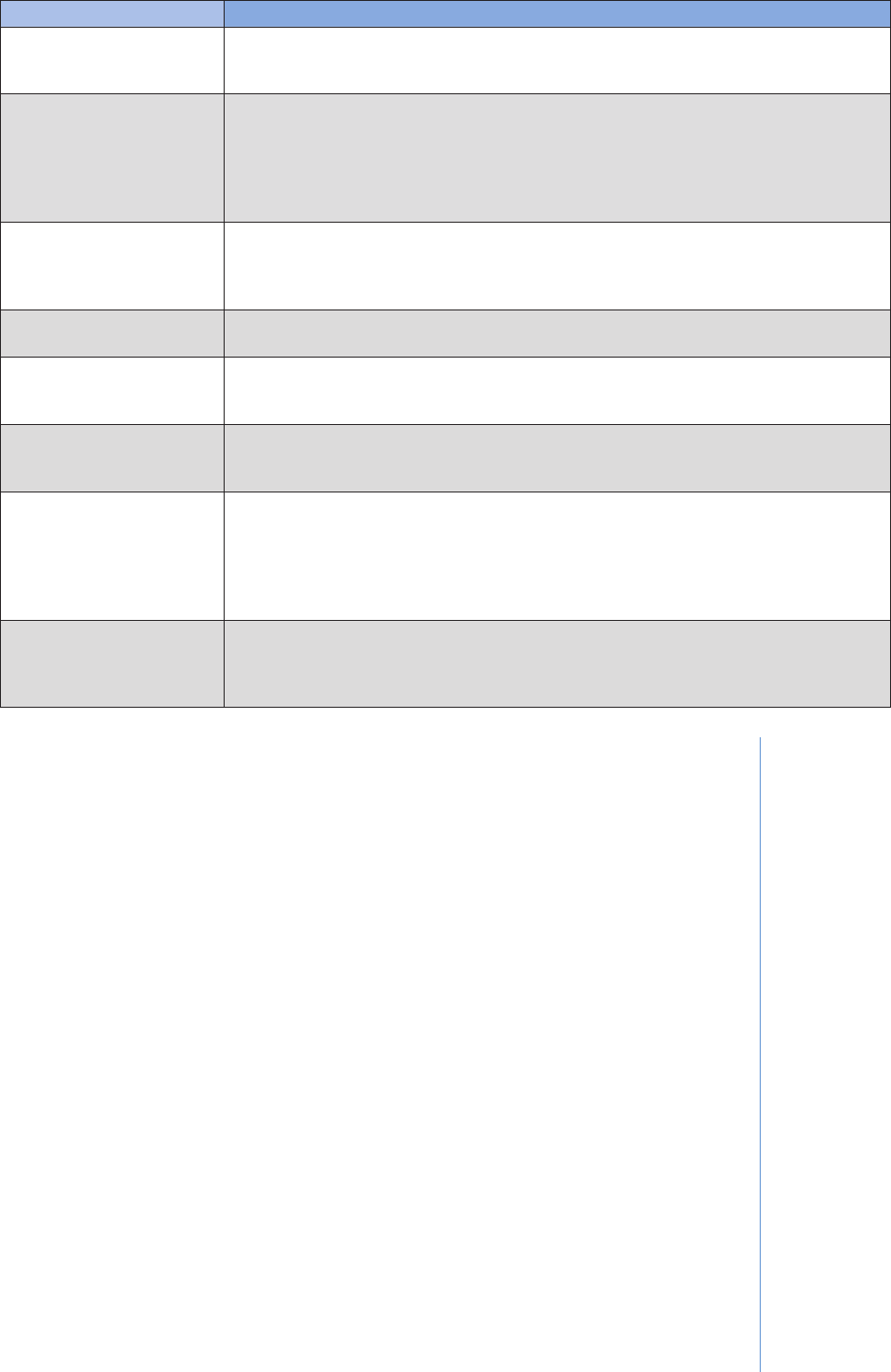

Goals Linkages

1. End poverty in all its forms everywhere. Trade is an engine of economic growth and poverty reduction.

2. End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition, and

promote sustainable agriculture.

Trade is an engine of economic growth, income and agricultural

production. Trade affects access, availability and stability of food

security.

5. Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Trade can provide opportunities for the economic empowerment

of women.

7. Ensure access to affordable, reliable, sustainable and modern

energy for all

Trade and global value chains are drivers of technological

innovation and the production of renewable energy sources.

8. Promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full

and productive employment and decent work for all.

Trade can be an engine of economic growth and employment.

9. Build resilient infrastructure, promote inclusive and sustainable

industrialization, and foster innovation.

Trade can be an engine of economic growth and industrialization.

10. Reduce inequality within and among countries. Trade-led growth has often contributed to reducing inequality

between countries.

17. Strengthen the means of implementation and revitalize the global

partnership for sustainable development.

Trade is a key means of implementation for sustainable

development.

Table 1. Potential linkages between trade and sustainable development goals

restricting market access is more than twice

that of tariffs. The impact is particularly striking

in sectors of high relevance for developing

countries.

3

The development potential of trade can be

signicantly impaired by trade costs stemming

from non-tariff measures. However, the elimination

of such measures is rarely an option, as the direct

linkages to sustainable development will show.

Reducing the cost of non-tariff

measures without compromising policy

objectives

There are two principal means of bringing

down trade costs related to non-tariff measures

without even touching policy levels: by increasing

transparency and reducing procedural obstacles.

Despite the widespread use of non-tariff

measures, there is a broad transparency gap.

This poses a major challenge to developing

countries with limited recourses as they assess

the implications of non-tariff measures. UNCTAD

and several of its partners are spearheading an

international initiative to collect comprehensive

data of mandatory regulations currently in force

in many countries. Detailed information for each

non-tariff measure includes information sources,

measures, and products and countries affected.

Coverage of over 90 per cent of world trade is

envisaged for 2015 (http://unctad.org/ntm). Data

collection of non-tariff measures is essential for

UNCTAD research and technical cooperation.

Every non-tariff measure comes with an

implementation procedure. As a rule, associated

procedures become more burdensome as the

underlying non-tariff measure becomes more

complex or discretionary. This incurs additional

costs and in many cases, long delays. The

World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Trade

Facilitation has the potential to drastically reduce

procedural obstacles and delays at the border.

Direct linkages: Many non-tariff

measures are much more than trade

policy instruments

Increasingly, non-tariff measures are sanitary,

phytosanitary measures and technical barriers to

trade designed to protect the environment and

human, animal and plant life. Mostly applied in a

non-discriminatory way to domestic and foreign

rms, they directly regulate issues related to

sustainable development goals: food, nutrition

and health, sustainable energy, sustainable

production and consumption, climate change

that can have an economic effect on international

trade.

2

They thus include a wide array of policies.

Some are traditional instruments of trade policy,

such as quotas or trade defence measures. These

measures are often termed non-tariff barriers

because of their unequivocally discriminatory and

protective nature.

However, the distinctly neutral denition of non-

tariff measures does not imply a direction of

impact or a judgement about the legitimacy of

a measure. It notably comprises sanitary and

phytosanitary measures and technical barriers

to trade, which may equally apply to domestic

producers and stem from non-trade objectives

related to health and environmental protection.

Many linkages between non-

tariff measures and sustainable

development

The diversity of types, mechanisms and objectives

of non-tariff measures are also reected in

the sheer number of linkages to dimensions

of sustainability. To understand how non-tariff

measures interact with sustainable development,

it is helpful to distinguish between indirect and

direct linkages.

Indirect linkage means that non-tariff measures

inuence trade. In turn, trade can foster economic

development and spill over to sustainable

development.

Direct linkages refer to policies that have an

immediate effect on sustainability. While many

policies primarily aim at protecting health or the

environment, they also have an impact on trade

and are therefore considered non-tariff measures.

While voluntary private standards are not within

the scope of mandatory non-tariff policies, they

can also inuence sustainable development

directly and indirectly. And although positive

effects on economic, social and environmental

aspects of development are possible, the

fragmentation of standards is cause for concern.

Indirect linkages:

Trade costs slow down trade

Based on the premise that trade is a driver of

economic growth and development, non-tariff

measures may be viewed as trade costs, or non-

tariff barriers. Nevertheless, even legitimate non-

tariff measures with non-trade objectives can

have signicantly restrictive and distorting effects

on international trade. UNCTAD research shows

that the contribution of non-tariff measures to

2 UNCTAD, 2010, Non-tariff Measures: Evidence from Selected Developing Countries and Future Research Agenda

(New York and Geneva, United Nations publication).

3 UNCTAD, 2013, Non-tariff Measures to Trade: Economic and Policy Issues (New York and Geneva, United Nations

publication).

Regulatory convergence is paramount

Striking a balance between excessive trade

restrictions and serving crucial non-trade

objectives is a key challenge.

World Trade Organization agreements on

sanitary, phytosanitary and technical barriers

to trade contain valuable principles calling for a

science-based approach, and adherence and

harmonization to international standards.

Since such barriers to trade vary across

countries, harmonization is a complex policy

priority. Studies on their harmonization nd

that divergence from international standards

leads to signicant trade losses. Furthermore,

even measures applied in a non-discriminatory

manner implicitly discriminate against

developing countries, especially least developed

countries, which dispose of limited resources

and infrastructure to deal with complex technical

regulations that differ across markets.

4

and the environment (table 2). Clearly, these

measures are necessary, if only to ensure the

protection of the planet.

It is also clear that most of these non-tariff

measures restrict trade and indirectly, economic

development. Direct and indirect linkages

between non-tariff measures and sustainable

development are not mutually exclusive: most

non-tariff measures with direct linkages also

create an indirect impact through trade. Take the

example of sanitary and phytosanitary regulations

to restrict pesticide residues on food products.

This non-tariff measure directly contributes to

human health and nutrition; however, it also

restricts trade, causing reduced income in

exporting countries and higher consumer prices

in importing countries.

There are indead tough trade-offs between

trade restrictions and direct sustainability to be

considered.

Goals Measures

Goal 2. End hunger, achieve food

security and improved nutrition, and

promote sustainable agriculture.

Non-tariff measures in the shape of sanitary and phytosanitary measures and technical barriers to trade are directly linked

to several pillars of food security. Sanitary and phytosanitary measures protect the health of human beings, animals and

plants; they also offer crop protection against pests and diseases.

Goal 3. Ensure healthy lives and

promote well-being for all.

Non-tariff measures or sanitary and phytosanitary measures are employed to protect human health from risks arising

from additives, contaminants, toxins or disease-causing organisms in food and drink. Codex Alimentarius provides

recommendations for science-based sanitary and phytosanitary regulations. Technical barriers to trade allow countries to

regulate food for consumer protection, e.g. labelling of fat or sugar contents. Non-tariff measures or technical barriers to

trade regulate the safety of imported pharmaceutical products and hazardous substances that may have adverse effects

on human health.

Goal 7. Ensure access to affordable,

reliable, sustainable and modern

energy for all.

Non-tariff measures apply to clean energy products in different ways. Some countries use subsidies, often “feed-in tariffs”,

to promote imports and the use of clean energy technologies. Some apply local content requirements for these benets,

which may slow down the proliferation of clean energy sources. Photovoltaic products have been subject to non-tariff

measures or antidumping duties.

Goal 12. Ensure sustainable

consumption and production patterns.

Non-tariff measures or technical barriers to trade enable countries to regulate production and imports of products that

cause environmental damage.

Goal 13. Take urgent action to combat

climate change and its impacts.

Non-tariff measures or technical barriers to trade are employed to regulate production and trade with respect to carbon

footprints, in accordance with the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Kyoto Protocol. Trade

restrictions of ozone-depleting substances and products under the Montreal Protocol have reduced global warming.

Goal 14. Conserve and sustainably use

oceans, seas and marine resources for

sustainable development.

The primary objective of non-tariff measures or technical barriers to trade is to protect the environment. Measures include

restrictions on trade with hazardous substances or pollutants harming aquatic or terrestrial ecosystems. These restrictions

are often related to multilateral agreements such as the Basel Convention and the London Convention.

Goal 15. Protect, restore and

promote sustainable use of terrestrial

ecosystems, sustainably manage

forests, combat desertication, and

halt and reverse land degradation and

halt biodiversity loss.

Countries restrict trade of endangered ora and fauna through technical barriers to trade, often in alignment with the

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species Wild Fauna and Flora. Non-tariff measures/sanitary and

phytosanitary and technical barriers to trade protect ecosystems and biodiversity from pests and invasive species.

Goal 17. Strengthen the means

of implementation and revitalize

global partnership for sustainable

development.

All of the above direct linkages between non-tariff measures and sustainable development show a strong need for global

partnership and coordination.

Table 2. Direct linkages between non-tariff measures and sustainable development goals

4 W Czubala, B Shepherd and JS Wilson, 2009, Help or hindrance? The impact of harmonised standards on African

Exports, Journal of African Economies, 18(5):711–744, November; UNCTAD, 2014, Trading with Conditions:

The Effect of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures on Lower Income Countries’ Agricultural Exports (New York

and Geneva, United Nations publication); UNCTAD, 2015, Deep Regional Integration and Non-tariff Measures:

A Methodology for Data Analysis (New York and Geneva, United Nations publication).

UNCTAD/PRESS/PB/2015/9 (No. 37)

implementation of sustainable development

goals.

Non-tariff measures are powerful policy tools that

can directly inuence sustainable development.

It is conceivable that a further proliferation of

such measures will occur as a reaction to the

direct linkages between them and sustainable

development goals.

Crucially, however, the direct impacts of non-

tariff measures on sustainability must not be

considered in isolation. Indirect linkages, which

may restrict trade and slow down economic

development, should not be ignored. These two

sides of the same coin create trade-offs as well

as synergies.

Coordination across areas of

expertise is indispensable

Linkages between non-tariff measures and

sustainable development goals put another

emphasis on the integrated nature and ambition

of the post-2015 development agenda. Non-tariff-

measure-related linkages between economic,

social and environmental development need to

be acknowledged and addressed. Coordination

is key.

National policymakers should look beyond their

own areas of expertise and ministerial mandates.

In fact, ministries of agriculture and health tend to

regulate more non-tariff measures than ministries

of trade. It is recommended that countries set

up national coordinating committees to ensure

regulatory coherence.

Equally, United Nations funds, programmes and

specialized agencies should not focus solely

on the implementation of a goal that relates to

their core competency. Strong inter-agency

cooperation is required to achieve sustainable

development. The United Nations must indeed

“Deliver as one”.

6

Nations need to work together in the multilateral

system and the United Nations to achieve

regulatory convergence. Most sustainable

development challenges cannot be achieved

alone. In the case of non-tariff measures, a

fragmentation of country-specic requirements

can severely handicap countries’ trade-driven

development prospects. The streamlining

and harmonization of non-tariff measures can

strongly mitigate trade-restrictive effects, while

directly and positively inuencing sustainability of

development.

While sanitary and phytosanitary regulations

are necessary (e.g. for food safety), commonly

agreed science-based international standards

should facilitate trade by harmonizing the

production process across countries. In practice,

the harmonization of standards should reduce

many xed and variable costs of trade.

Multilateral harmonization creates

trade; bilateral and regional

harmonization diverts it

The multilateral system is confronted with

a growing “spaghetti bowl” of bilateral and

regional agreements that also increasingly aim at

recognizing or harmonizing requirements relating

to sanitary, phytosanitary and technical barriers

to trade. The question is, how to harmonize

non-tariff measures to generate sustainable

development?

Studies show that adopting science-based

international standard guidelines is generally

good for developing countries. However, their

participation in international standard-setting

bodies needs to be strengthened. Regional

and bilateral harmonization also creates trade,

but with potential trade diversion effects.

Unilaterally adopting more stringent standards

from developed markets and imposing them as

domestic production requirements may increase

exports to the North, but this also carries risks.

For example, rising product prices can have a

negative impact on domestic consumers and

South–South trade.

5

Multilateral conventions, such as the Montreal

Protocol, play a signicant role in ensuring

sustainability while minimizing trade impacts.

Examples of effective multilateral collaboration

and coherence are provided in table 2.

International standard guidelines are not binding,

however. Some countries observe them, whereas

others are more or less strict about food safety.

Similarly, many international conventions are legally

binding plurilateral agreements for signatories,

while non-signatories tend to lag behind in their

contribution to global environmental sustainability.

Therefore, strengthening multilateral cooperation

in the harmonization of non-tariff measures is

paramount.

Synergies and trade-offs between

means of implementation must be

exploited

Given the multidimensionality of issues related

to non-tariff measures, they are indeed relevant

to the post-2015 development agenda and the

Contact

Christian Knebel

41 22 9175553

or Ralf Peters

41 22 9175680

Trade Analysis Branch

DITC, UNCTAD

Press Ofce

41 22 917 58 28

www.unctad.org

5 AC Disdier, L Fontagné and O Cadot, 2014, North–South standards harmonization and international trade, World

Bank Economic Review, 29(2):327–352.

6 http://www.un.org/en/ga/deliveringasone, accessed 14 September 2015.