Accessible Version

PAYMENTSERVICES

FederalReserve’s

Competitionwith

OtherProviders

BenefitsCustomers,

butAdditional

ReviewsCould

IncreaseAssuranceof

CostAccuracy

ReporttotheChairman,Committeeon

FinancialServices,Houseof

Representatives

August 2016

GAO-16-614

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-16-614, a report to the

Chairman, Committee on Financial Services,

House of Representatives

August 2016

PAYMENT SERVICES

Federal Reserve’s Competition with Other Providers

Benefits Customers, but Additional Reviews Could

Increase Assurance of Cost Accuracy

Why GAO Did This Study

Federal Reserve Banks compete with

private-sector entities to provide

services while Federal Reserve Board

staff also supervise the Reserve Banks

and other service providers and

financial institution users of these

services. The Monetary Control Act

requires the Federal Reserve to

establish fees for its services on the

basis of costs, including certain

imputed private-sector costs. GAO was

asked to review issues regarding the

Federal Reserve’s role in providing

payment services. Among other

objectives, GAO examined (1) how

well the Federal Reserve calculates

and recovers its costs, (2) the effect of

the Federal Reserve on competition in

the market, and (3) market participant

views on the Federal Reserve’s role in

the payments system.

GAO analyzed cost and price data

trends; reviewed laws, regulations, and

guidance related to Federal Reserve

oversight and provision of payment

services; and interviewed Federal

Reserve officials, relevant trade

associations, randomly selected

payment service providers, customer

financial institutions, and other market

participants.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that the Federal

Reserve consider ways to incorporate,

where appropriate, additional costs

faced by private-sector competitors in

its simulated cost recoveries and

periodically obtain an external audit

that tests the accuracy of the methods

it uses to capture and simulate its

costs. The Federal Reserve noted

steps they will take to address GAO’s

recommendations.

What GAO Found

The Federal Reserve Banks are authorized to provide payment services—such

as check clearing and wire transfers—to ensure continuous and equitable access

to all institutions. The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control

Act of 1980 (Monetary Control Act) requires the Federal Reserve to establish

prices for its payment services on the basis of the costs incurred in providing the

services and give due regard to competitive factors and the provision of an

adequate level of services nationwide. GAO found the Federal Reserve had a

detailed cost accounting system for capturing these costs that generally aligned

with federal cost accounting standards. Although this system was evaluated and

found effective by a public accounting firm in the 1980s, it has not undergone a

detailed independent evaluation since then. In addition to the actual costs it

incurs in providing services, the Federal Reserve also must include an allocation

of imputed costs which takes into account the taxes that would have been paid

and the return on capital that would have been provided if the services had been

furnished by a private firm. Although its processes for simulating the imputed

costs generally were reasonable, the Federal Reserve did not impute certain

compliance costs private-sector firms can face—such as for planning for

recovery and orderly wind down after financial or other difficulties. Including

additional simulated costs competitors can incur and obtaining periodic external

evaluations of its cost accounting practices would provide greater assurance that

the Federal Reserve fully includes appropriate costs when pricing its services.

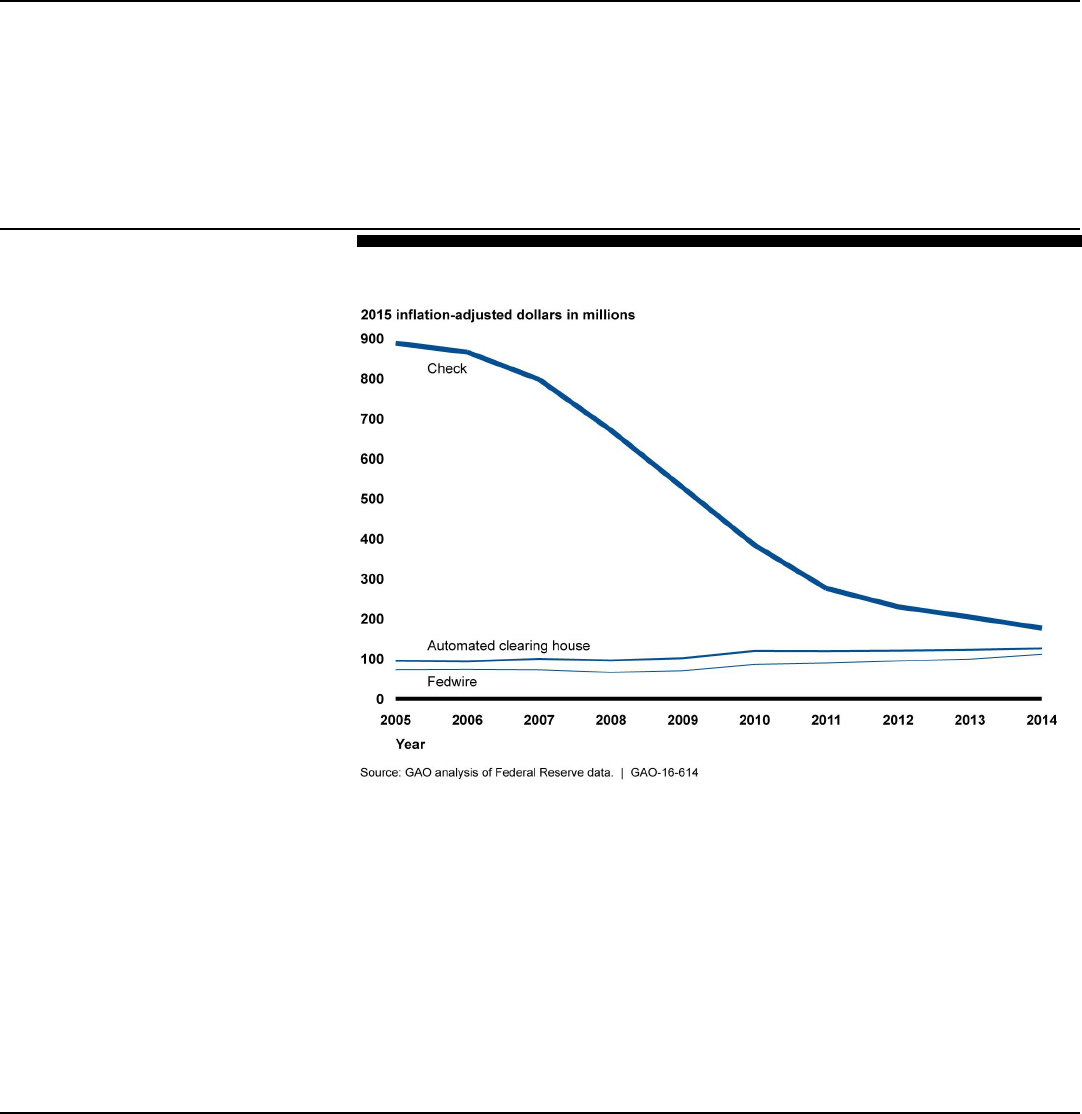

Since the mid-2000s, the effects of Federal Reserve participation in the payment

services market have included lower prices for many customers; overall market

share for competitors also increased. Although some competitors raised

concerns about some Federal Reserve pricing practices, customers GAO

interviewed generally were satisfied with its services and prices. The Federal

Reserve also has a process for assessing its pricing and products to help ensure

it is not unfairly leveraging any legal advantages. Since 2005, the Federal

Reserve lowered prices for checks and smaller electronic payments while

increasing prices for wire transfers. During this time, private-sector competitors’

market share expanded overall. But the Federal Reserve’s only competitor in

small electronic payments and wire transfers told GAO that increased regulatory

costs and competitive pressure from the Federal Reserve creates difficulties for

the long-term viability of private-sector operators.

Most market participants GAO interviewed were satisfied with how the Federal

Reserve performed various regulatory and service provider roles in the payments

system. Most of the 24 participants GAO interviewed had no concerns over how

the Federal Reserve separated its supervisory activities from its payment

services activities. The Federal Reserve also has begun collaborating with

market participants to pursue improvements to the safety, speed, and efficiency

of the payment system. Although some competitors said the Federal Reserve

should reduce its payment services role, many participants supported having the

Federal Reserve remain an active provider. Federal Reserve staff indicated that

these activities provide the Federal Reserve with sufficient revenue to enable it to

provide ubiquitous access at affordable prices.

View GAO-16-614. For more information,

contact Lawrance Evans at (202) 512-8678 or

Letter 1

Page i GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Background 3

Federal Reserve Has Processes in Place to Comply with Cost

Recovery Requirements 16

While Some Competitors Expressed Concerns about Some

Federal Reserve Payment Service Practices, Users Appeared

to Benefit 34

Market Participants Generally Viewed the Federal Reserve as

Managing Potential Payment Services Conflicts 51

Market Participants Generally Support a Continued Role for the

Federal Reserve in the Payments System 57

Conclusions 64

Recommendations for Executive Action 64

Agency Comments, Third-Party Views, and Our Evaluation 65

Appendix I: Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 67

Appendix II: Federal Reserve Payment Services Cost Accounting 72

Appendix III: Private Sector Adjustment Factor (PSAF) Methodology 75

Appendix IV: Competitive Impact Assessment Process 79

Appendix V: Comments from the Federal Reserve 83

Appendix VI: GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 86

Appendix VII: Accessible Data 87

Agency Comment Letter 87

Data Tables 90

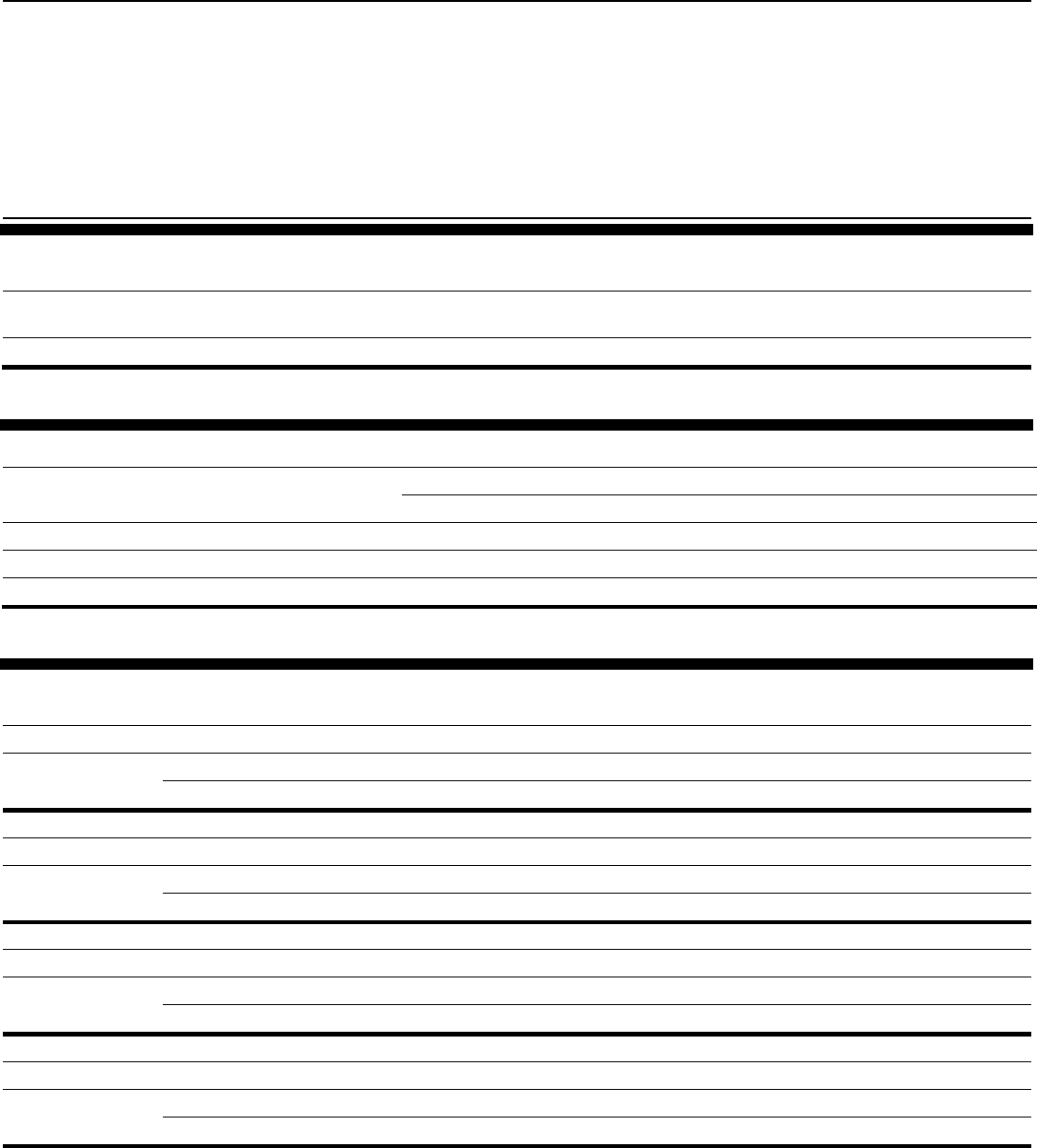

Tables

Table 1: Annual Cost Recovery Percentages for the Federal

Reserve, by Payment Service Type, 2007—2015

(percentage) 30

Table 2: 2014 Federal Reserve Payment Services Direct and

Indirect Costs (in Dollars) 73

Table 3: Component Expenses Calculated by the Federal

Reserve’s Private-Sector Adjustment Factor (PSAF) in

2015 and 2016, dollars in millions 77

Contents

Data Table for Figure 4: U.S. Noncash Payments by Transaction

Type, 2000–2012 90

Data Table for Figure 5: Rolling 10-year Average Cost Recovery

Rates for Federal Reserve Payment Services, 1996-2015

(percentage) 91

Data Table for Figure 6: Federal Reserve Revenues by Payment

Service, 2005–2014 (2015 Dollars in Millions) 91

Data Table for Figure 7: Market Shares (Based on Dollar Volume)

of Federal Reserve and Private-Sector Providers in

Check, Automated Clearing House (ACH), and Wire

Transfer Payments, 2001–2013 91

Figures

Page ii GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Figure 1: Steps Involved in a Typical Check Payment in the United

States 6

Figure 2: Steps Involved in a Typical Wire Transfer Payment in the

United States 8

Figure 3: Example of Steps Involved in an Automated Clearing

House Payment from a Business to an Individual in the

United States 10

Figure 4: U.S. Noncash Payments by Transaction Type, 2000–

2012 15

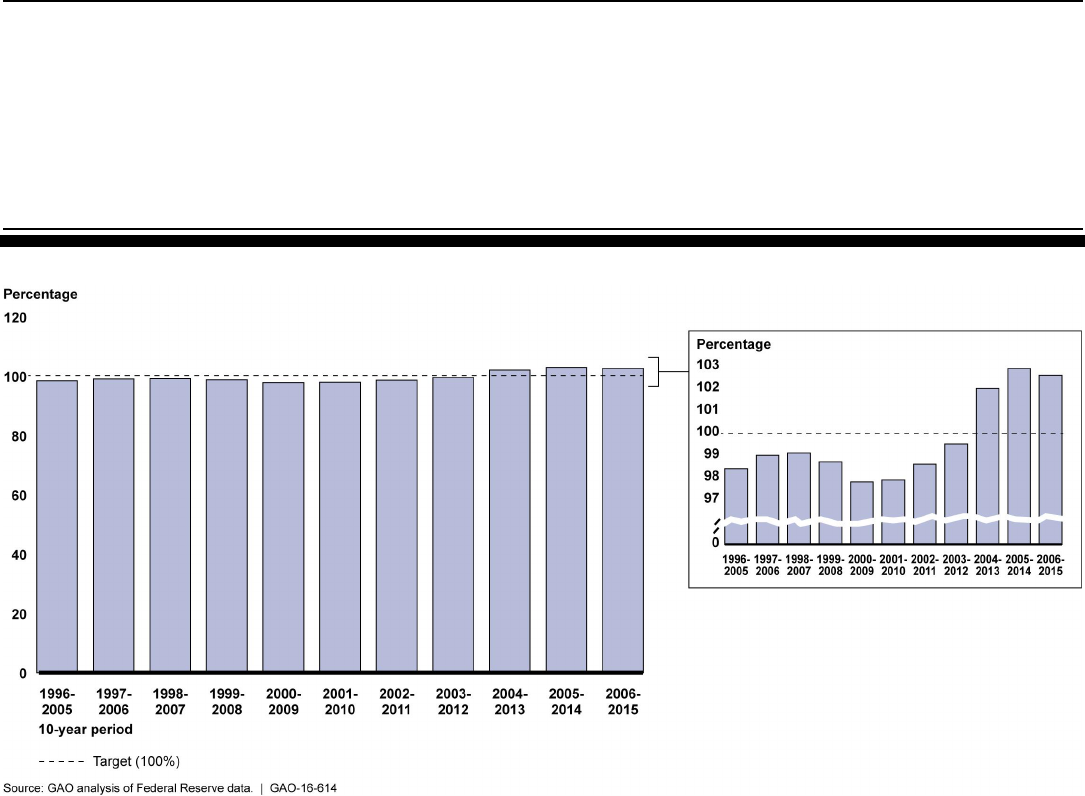

Figure 5: Rolling 10-year Average Cost Recovery Rates for

Federal Reserve Payment Services, 1996-2015

(percentage) 29

Figure 6: Federal Reserve Revenues by Payment Service, 2005–

2014 (2015 Dollars in Millions) 31

Figure 7: Market Shares (Based on Dollar Volume) of Federal

Reserve and Private-Sector Providers in Check,

Automated Clearing House (ACH), and Wire Transfer

Payments, 2001–2013 47

Page iii GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Abbreviations

ACH Automated Clearing House

Board Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

Check 21 Check Clearing for the 21st Century Act of 2003

CHIPS Clearing House Interbank Payment Service

ECCHO Electronic Check Clearing House Organization

Federal Reserve Federal Reserve System

PACS Planning and Control System

PSAF private-sector adjustment factor

Reserve Banks Federal Reserve Banks

TCH The Clearing House Payments Company L.L.C.

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

August 30, 2016

The Honorable Jeb Hensarling

Chairman

Committee on Financial Services

House of Representatives

Dear Mr. Chairman:

With the value of checks and electronic payment transfers exceeding a

quadrillion dollars in 2015, a reliable and efficient payments system is

essential for the economic stability of the United States. The Board of

Governors (Board) and the 12 Federal Reserve Banks of the Federal

Reserve System (Federal Reserve) play multiple roles in the payments

system, including functioning as the nation’s central bank, supervising

financial institutions, and providing payment services to market

participants. The Reserve Banks offer a range of payment services to

depository institutions and the federal government, including collecting

checks; electronically transferring funds; issuing, transferring, and

redeeming U.S. government securities; distributing and receiving

currency and coin; and maintaining accounts for reserve and clearing

balances.

1

The Board oversees the operations of the Reserve Banks and

serves as a regulator of certain aspects of payment services in the United

States. As part of its oversight, the Board issues regulations that apply to

the payment services activities of the Reserve Banks and the private-

sector entities that compete with them. Where these roles potentially

overlap or conflict, the Federal Reserve faces the challenge of managing

or separating the roles in ways that help ensure it fulfills each role without

exerting undue influence or giving itself an advantage at the expense of

1

As the nation’s central bank, one of the Federal Reserve’s tools for conducting monetary

policy is the setting of reserve requirements that mandate that all depository institutions

hold a percentage of certain types of deposits as reserves in the form of vault cash, as a

deposit in the institution’s account at a Federal Reserve Bank, or as a deposit in a pass-

through account at a correspondent institution (one that provides check clearing and other

services for other institutions). See 12 U.S.C. §§ 248, 461; 12 C.F.R. § 204.5(a), (d). More

than 6,000 U.S. depository institutions maintain a Federal Reserve account at the Reserve

Bank in their district and about 1,900 of these account holders maintain balances for the

purposes of satisfying reserve requirements on behalf of themselves or other depository

institutions, and these accounts also can be used to settle payments.

Letter

the banking industry or its private-sector competitors in providing payment

services.

In 2000, we reviewed the potential conflicts of interest posed by the

Federal Reserve’s operation of a payment system that competes with

private-sector systems operated and owned by institutions that the

Federal Reserve also supervises.

Page 2 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

2

We found no evidence to suggest that

the Federal Reserve had not adequately separated its multiple roles in

the payments system. However, the overall U.S. payments system has

evolved since our 2000 report. Technology has dramatically changed

many aspects of the payments process, notably in the transition from the

use and settlement of paper checks to electronic payments. In addition,

the Federal Reserve has begun publicly exploring how the United States

can develop a near real-time payment system to facilitate payments

between individuals and businesses as several other countries are

moving to. When Congress mandated that the Reserve Banks offer

payment services to nonmember depository institutions on terms

comparable to those for member banks, it also required that the Banks

publish prices for these services that were established over the long run

on the basis of all the direct and indirect costs actually incurred in

providing the services, including certain imputed costs that would have

been incurred if the services had been furnished by a private firm.

You asked us to update our 2000 report and in particular, review the

Federal Reserve’s management of its potential conflicts of interest in the

U.S. payments system, including issues relating to the costs and pricing

of its services. This report examines (1) how effectively the Federal

Reserve captures and recovers its payment services costs; (2) the effect

of the Federal Reserve’s practices on competition in the payment

services market; (3) how the Federal Reserve mitigates the inherent

conflicts posed by its various roles in the payments system; and (4)

market participant viewpoints on the future role of the Federal Reserve in

the payments system. This report focuses on three payment system

products offered by the Federal Reserve—check clearing, electronic

payments known as Automated Clearing House (ACH) payments, and

wire transfer payments—because these are the services in which the

Federal Reserve primarily competes with private-sector entities.

2

GAO, Federal Reserve System: Mandated Report on Potential Conflicts of Interest,

GAO-01-160 (Washington, D.C.: Nov. 13, 2000).

To address these objectives, we analyzed data on the reported costs and

revenues of Federal Reserve payment services from 1996 to 2015 and

how pricing and fee structures for the services had changed over this

period. We took steps to assess the reliability of these data and

determined they were sufficiently reliable for our analysis. Although we

analyzed the processes by which the Federal Reserve accounts for its

reported costs and revenues, we did not include detailed testing of the

Federal Reserve’s cost accounting controls related to its priced services

activities. We reviewed relevant legislation and Federal Reserve policies,

regulations, and guidance relevant to payment services activities. We

reviewed audits that external and internal audit organizations performed

of Federal Reserve payment system costs and activities. We also

reviewed the Federal Reserve’s policies that outline the criteria it would

consider before offering a new payment service. We interviewed Board

and Reserve Bank staff and 34 market participants, including financial

trade associations whose members participate in payment systems and

issue rules governing payment system activities; payment services

providers, including those that compete with the Federal Reserve; and

banks and credit unions that were end users of payments systems

services from other private-sector providers and the Federal Reserve.

The sample of banks and the sample of credit unions we interviewed

were both composed of a nonprobability stratified sample based on tiers

by asset size, including interviewing the five largest banks and randomly

selecting a number of banks from the large, mid-sized, and smaller tiered

banks. For credit unions we randomly selected institutions from larger and

from smaller credit unions. We also interviewed both financial institution

and nonbank entities that provided competing payments services

randomly selected within type of institution. We also interviewed staff from

the Department of Justice about competition issues. For more information

on our methodology, see appendix I.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2014 to August

2016 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

The Federal Reserve has long had a role in the U.S. payments system.

One of the major impetuses for the creation of the Federal Reserve was

to reduce the potential for disruptions in payments that periodically

Page 3 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Background

occurred in the United States. During a financial crisis in 1907 stemming

from losses arising from the San Francisco fire and the failure of the

Knickerbocker Trust in New York City, payments were largely suspended

throughout the country because many banks and clearinghouses, which

served as centralized locations for banks to exchange checks for clearing,

refused to clear checks drawn on certain banks. These refusals led to

liquidity problems in the banking sector and the failure of otherwise

solvent banks, which exacerbated the impact of the crisis on businesses

and individuals.

With the passage of the Federal Reserve Act, Congress established the

Federal Reserve in 1913 in part as a response to these events.

Page 4 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

3

The

Federal Reserve Act also directed the Federal Reserve to supply

currency in the quantities demanded by the public and gave it the

authority to establish a national check-clearing system. Previously, some

paying banks (on which checks had been drawn) had refused to pay the

full amount of checks (nonpar collection) and some had been charging

other fees to the banks presenting checks to be paid. To avoid paying

these presentment fees, many presenting banks routed checks to banks

that were not charged presentment fees by paying banks. This circuitous

routing resulted in extensive delays and inefficiencies in the check-

collection system. In 1917, Congress amended the Federal Reserve Act

to prohibit banks from charging the Reserve Banks presentment fees and

to authorize nonmember banks as well as member banks to collect

checks through the Federal Reserve System.

4

As the nation’s central bank, the Federal Reserve manages U.S.

monetary policy, supervises certain participants in the banking system,

and serves as the lender of last resort. The Federal Reserve System

consists of the Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., and 12 Reserve

Banks with 24 branches located in 12 districts across the nation. The

Board is a federal agency, and the Reserve Banks are federally chartered

and organized like private corporations each with a board of directors and

with their shares owned by their member banks. The Board is responsible

for maintaining the stability of financial markets, supervising banks that

are members of the Federal Reserve and bank and savings and loan

holding companies, and overseeing the operations of the Reserve Banks.

3

Federal Reserve Act, Pub. L. No. 63-43, 38 Stat. 251 (1913).

4

Pub. L. No. 65-25, 40 Stat. 232 (1917).

The Board has delegated some of these responsibilities to the Reserve

Banks, which also provide payment services to depository institutions and

government agencies. As a result, the Federal Reserve has dual roles as

both payment systems operator and as a regulator of payment system

participants.

The role of the Federal Reserve Banks as a provider of several payment

services in the United States contrasts with that of the central banks of

other countries. According to a study by the Bank for International

Settlements, which provides services to other central banks, of the 13

foreign jurisdictions examined, central banks in 11 operated large value

payment transfer systems—as the Reserve Banks do—but only 2 central

banks (those in Belgium and Germany)—also operated check-clearing

and electronic retail payment networks.

Page 5 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

5

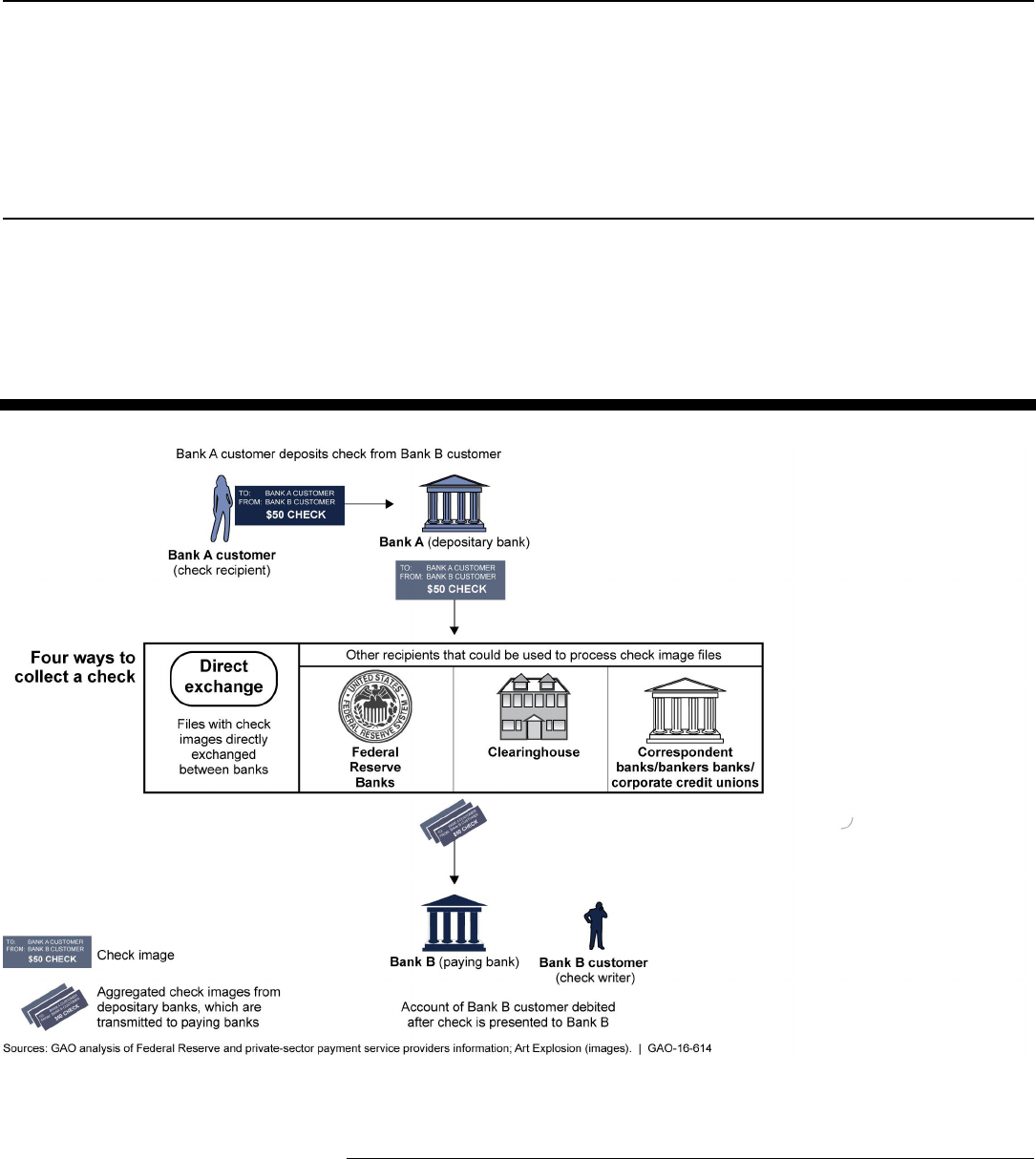

To improve the functioning of check services, Congress instituted a par-

value (face value) check collection service to simplify the check-clearing

process in the Federal Reserve Act, and gave the Federal Reserve

operational (through the Reserve Banks) and regulatory (through the

Board) roles in check collection. Interbank checks are cleared and settled

through a check-collection process that includes presentment and final

settlement.

6

Presentment occurs when checks are delivered by the bank

that received them—which currently almost exclusively involves

transmission of electronic images—to paying banks for payment. The

checks may be sent either directly to the paying bank or through another

entity—either another bank, a check clearinghouse, or a correspondent

bank—that would ultimately deliver them to the paying banks (see fig. 1).

The paying banks then decide to honor or return the checks. Settlement

ultimately occurs when collecting banks are credited and paying banks

debited, usually through accounts held at a Reserve Bank or at

correspondent banks that provide check clearing and other services for

other institutions. As part of its role in regulating check collection, the

5

See Bank for International Settlements, Committee on Payment and Settlement Systems

of the Group of Ten Countries, Payment and Settlement Systems in Selected Countries,

(Basel, Switzerland, April 2003). The 13 foreign jurisdictions reviewed were those in

Belgium, Canada, the Euro area, France, Germany, Hong Kong, Italy, Japan,

Netherlands, Singapore, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

6

Interbank checks are those in which the bank of first deposit and the paying bank are

different. “On-us” checks are deposited or cashed at the same bank on which they are

drawn.

Federal Reserve Board promulgated regulations that govern various

aspects of these processes, including Regulation CC (which covers how

quickly banks must make funds from checks and other deposits available

for withdrawal and governs aspects of interbank check collection and

return), and Regulation J (which covers how institutions can collect and

return checks and other items through the Reserve Banks).

Page 6 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

7

Figure 1: Steps Involved in a Typical Check Payment in the United States

7

For Regulation CC, see 12 C.F.R. pt. 229. Section 1086 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street

Reform and Consumer Protection Act amended the Expedited Funds Availability Act to

make the Board’s authority for the EFA Act’s provisions implemented in Subpart B of

Regulation CC joint with the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Pub. L. No. 111-203,

§ 1086, 124 Stat. 1376, 2085 (2010). For Regulation J, see 12 C.F.R. pt. 210.

To facilitate electronic check processing, some banks can create an

electronic image of a paper check at their branches, while others

transport the paper to centralized locations where the paper is imaged.

Page 7 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

8

After imaging, an image cash letter is assembled and sent directly to a

paying bank, an intermediary bank, or to a collecting bank (such as a

Reserve Bank or a correspondent bank) or to an image exchange

processor for eventual presentment to the paying bank. The Reserve

Banks offer imaged check products—FedForward, FedReceipt, and

FedReturn—for a fee to banks that use its check collection services to

present checks for payment at other institutions.

9

Similarly, other entities

that offer check-clearing services charge fees or use other mechanisms

to obtain compensation for such services, or institutions may not charge

each other when directly exchanging images.

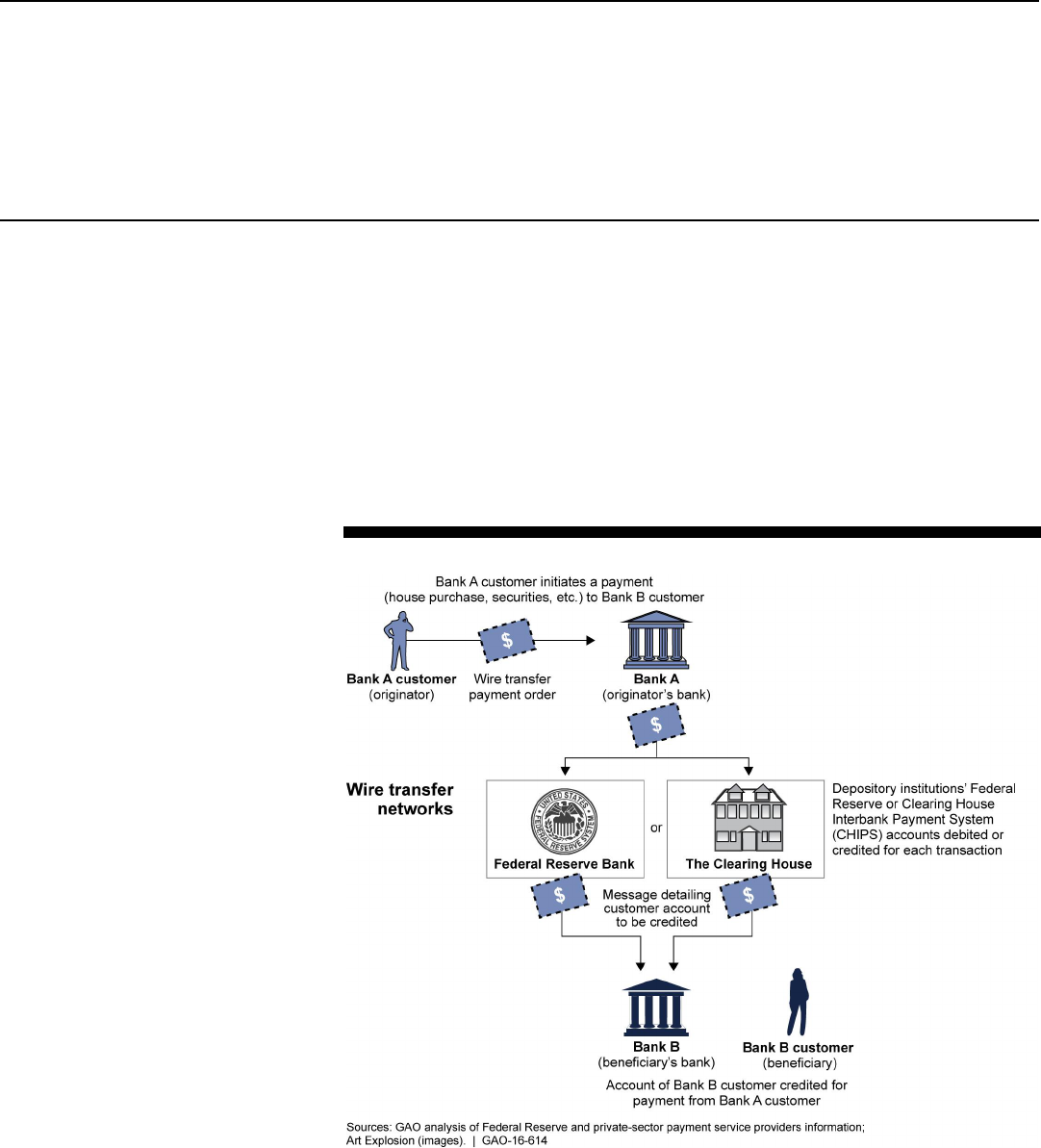

The Fedwire Funds Service (Fedwire), the Federal Reserve’s wire

payments service, began in 1918 as a funds transfer service and initially

used Western Union’s telegraph lines to transmit payments.

10

The current

Fedwire network provides a real-time gross settlement system in which

about 6,000 participants can initiate electronic funds transfers that are

immediate, final, and irrevocable. Depository institutions and others that

maintain an account with a Reserve Bank can use the service to send

payments directly to, or receive payments from, other participants.

Depository institutions also can use a correspondent relationship with a

8

Some check images are created by bank customers through a process called remote

deposit capture.

9

According to Federal Reserve staff, FedForward is a Reserve Bank service in which

checks are deposited with a Reserve Bank and presented for collection either as

substitute checks or electronically using image cash letters. (A cash letter is a group of

checks packaged and sent by one bank to another bank, clearinghouse, or a Reserve

Bank office. A cash letter is accompanied by a list containing the dollar amount of each

check, the total amount of the checks, and the number of checks sent with the cash letter.)

FedReceipt is a Reserve Bank service in which a paying bank agrees to permit the

Reserve Banks to present checks to it electronically. FedReturn is a Reserve Bank service

that permits paying banks to return checks to depository banks by sending image cash

letters to the Reserve Banks, which will return the checks in image cash letters or as

substitute checks to the depository banks.

10

In addition to the Fedwire Funds service, the Reserve Banks also provide the Fedwire

Securities Service, a securities settlement system that enables participants to hold,

maintain, and transfer eligible securities, including those issued by the U.S. Department of

the Treasury, other federal agencies, government-sponsored enterprises, and certain

international organizations, such as the World Bank. Securities are held and transferred in

book-entry form. This report will refer to the Fedwire Funds service as Fedwire.

Fedwire participant to make or receive transfers indirectly through the

system. Participants use Fedwire to handle time-critical payments (such

as settlement of interbank purchases, sales of federal funds, securities

transactions, real estate transactions, or disbursement or repayment of

large loans). The U.S. Department of the Treasury, other federal

agencies, and government-sponsored enterprises also use Fedwire to

disburse and collect funds. A private-sector entity, The Clearing House

Payments Company L.L.C. (TCH), operates a competing wire transfer

service—the Clearing House Interbank Payment System (CHIPS)—that is

used for similar purposes as Fedwire. Figure 2 shows how a typical wire

transfer payment occurs.

Figure 2: Steps Involved in a Typical Wire Transfer Payment in the United States

Page 8 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

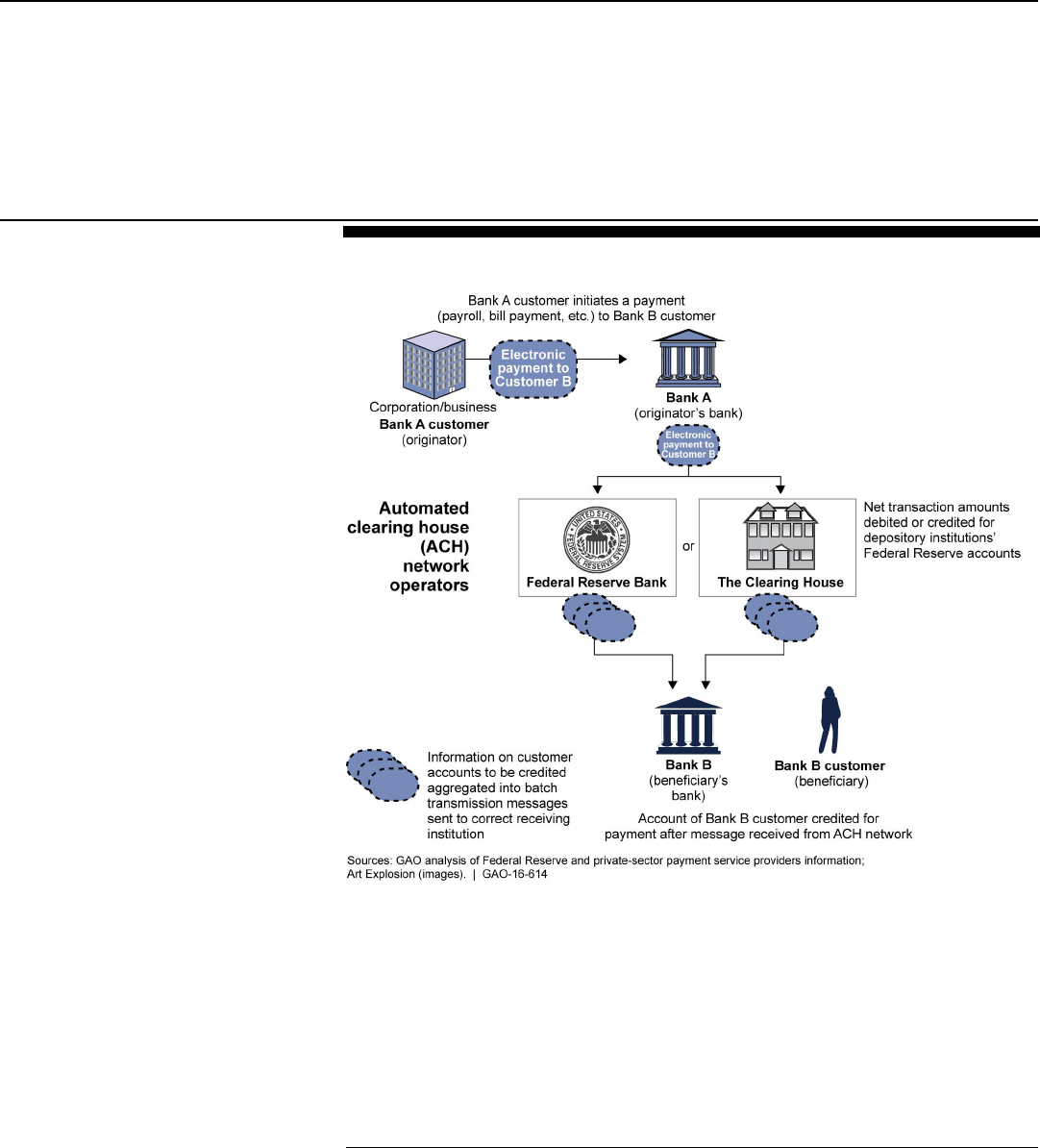

In response to concerns over high volumes of paper checks in the

payments system, the Federal Reserve worked with the private sector in

the 1970s to develop an electronic system to exchange payments known

as Automated Clearing House (ACH). These payments are often used for

small or recurring transactions, such as direct deposit of payrolls or

payment of utility, mortgage, or other bills. The Reserve Banks’ Retail

Payments Office operates an ACH payment network (called FedACH). By

agreement (in the form of an operating circular), ACH transactions are

conducted under rules and operating guidelines developed by a nonprofit

banking trade association, NACHA (formerly the National Automated

Clearing House Association). With limited exceptions, Federal Reserve

staff indicated that the Reserve Banks incorporate the association’s rules

by reference in their ACH operating circulars, which represents the

agreement between a Reserve Bank and its customers on the terms and

conditions of the FedACH services. TCH also operates its own ACH

network—the Electronic Payments Network—through which its members

can transmit and receive ACH payments to or from the customers of their

institutions. The Federal Reserve and TCH exchange ACH payments

originated by their customer institutions that are bound for institutions

using the other’s ACH network. Both the sending and the receiving

institutions typically are charged fees for ACH transactions. Figure 3

illustrates a typical ACH payment.

Page 9 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Figure 3: Example of Steps Involved in an Automated Clearing House Payment from

Page 10 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

a Business to an Individual in the United States

In 1980, Congress enacted changes that expanded the role of the

Federal Reserve in the payments system. The Monetary Control Act of

1980 (Monetary Control Act) extended the Federal Reserve’s reserve

requirements to all depository institutions, not just member banks of the

Federal Reserve.

11

The act also allowed the Reserve Banks to offer

payment services to all depository institutions that had previously been

available at no cost to their members. Part of the legislative history of the

11

Pub. L. No. 96-221, Tit. I, 94 Stat. 132, 132 (1980). Requiring that depository institutions

hold a percentage of certain types of deposits as reserves in the form of vault cash or as

deposits at accounts at a Federal Reserve Bank or a correspondent institution is one of

the tools the Federal Reserve uses for conducting monetary policy. This act’s extension of

these reserve requirements to all institutions was to increase their effectiveness in

achieving desired changes in the money supply.

Monetary Control Act indicates that since the act required nonmember

institutions to meet reserve requirements, it was reasonable to also

provide such institutions with access to Reserve Bank payment

services.

Page 11 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

12

At this time, the act required the Federal Reserve to begin

charging all institutions for such services.

Because this change placed the Reserve Banks and private-sector

providers of payment services in competition with each other, the act

included certain requirements to encourage competition between the

Reserve Banks and private-sector providers to ensure provision of

payment services at an adequate level nationwide. The Monetary Control

Act required the Board to establish a fee schedule for Reserve Bank

payment services, under which all services are required to be priced

explicitly. The act also required that over the long run, fees be established

on the basis of all direct and indirect costs actually incurred in providing

the priced services, including imputed costs that would have been

incurred by a private-sector provider, giving due regard to competitive

factors and the provision of an adequate level of such services

nationwide.

13

In describing the policies adopted to implement the

12

126 CONG. REC. 6897 (1980) (statement of Sen. Proxmire).

13

12 U.S.C. § 248a. The Monetary Control Act requires that the Federal Reserve Board

establish the schedule of fees for the following services: (1) currency and coin services;

(2) check clearing and collection services; (3) wire transfer services; (4) automated

clearing house services; (5) settlement services; (6) securities safekeeping services; (7)

Federal Reserve float; and (8) any new services that the Federal Reserve System offers,

including but not limited to payment services to effectuate the electronic transfer of funds.

The act also directed the Board to publish (for public comment) a set of pricing principles

and a proposed schedule of fees based on those principles and then to put into effect the

fee schedule which is based on those principles. The schedule of fees prescribed must be

based on enumerated principles: (1) All Federal Reserve Bank services covered by the

fee schedule shall be priced explicitly. (2) All Federal Reserve Bank services covered by

the fee schedule shall be available to nonmember depository institutions and such

services shall be priced at the same fee schedule applicable to member banks, except

that nonmembers shall be subject to any other terms, including a requirement of balances

sufficient for clearing purposes, that the Board may determine are applicable to member

banks. (3) Over the long run, fees shall be established on the basis of all direct and

indirect costs actually incurred in providing the Federal Reserve priced services, including

interest on items credited prior to actual collection, overhead, and an allocation of imputed

costs, which takes into account the taxes that would have been paid and the return on

capital that would have been provided had the services been furnished by a private

business firm, except that the pricing principles shall give due regard to competitive

factors and the provision of an adequate level of such services nationwide. (4) Interest on

items credited prior to collection shall be charged at the current rate applicable in the

market for federal funds.

requirements of the Monetary Control Act, the Board stated that the act’s

legislative history indicated Congress sought to encourage competition to

ensure that these services would be adequately available nationwide and

at the lowest cost to society. According to these Board policies, the

Reserve Banks provide payment services to promote the integrity and

efficiency of the payments mechanism and ensure that payment services

are provided to all depository institutions on an equitable basis and in an

environment of competitive fairness.

Page 12 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

14

In participating in the payments system, the Federal Reserve has taken

various actions to make the system more efficient. For example, in the

1950s the Federal Reserve contributed to the adoption of magnetic ink

character recognition, which allowed routing and other processing

information to be printed in machine-readable ink on the bottom of the

check’s face, which helped automate check processing. As discussed

earlier, the Federal Reserve worked with the private sector to develop the

ACH system in the 1970s. Initially, ACH volumes were low with most

volume growth attributed to government-initiated transactions, because

high startup costs made private-sector banks reluctant to invest in and

use the network. For a few years following the implementation of the

Monetary Control Act, the Federal Reserve subsidized the ACH network,

which helped the network obtain sufficient volume to become successful.

To improve the clearing of checks, Congress passed the Check Clearing

for the 21st Century Act (Check 21), which became effective October 28,

2004, which was legislation supported by the Federal Reserve.

15

Check

21 facilitates check truncation, which is the substitution of the original

physical check with a legal equivalent (called a substitute check).

16

According to the trade association that establishes rules for exchanging

check images, checks are generally processed as images.

14

Federal Reserve System, Policies: The Federal Reserve in the Payments System,

Issued 1984, revised in 1990.

15

Pub. L. No. 108-100, 117 Stat. 1177 (2003).

16

According to Federal Reserve staff, banks are required to present paper checks unless

they have the agreement of the paying bank to accept electronic presentment. By creating

the concept of a substitute check, this act allowed banks earlier in the collection chain to

transmit electronically because the presenting bank has a means of creating the legal

equivalent of the paper check for presentment if need be (and likewise paying banks that

have some legal obligation to provide “original” checks were able to provide a substitute

check).

In 1998, a committee of senior Federal Reserve executives examined

whether the Federal Reserve’s participation in the payments system

remained justified in light of changes occurring in the financial services

and technology sectors at the time. This committee’s report addressed

the results of its review of the role the Federal Reserve played in the use

of checks and ACH payments in the retail payments system, including

considering whether any changes in its role could affect the integrity,

efficiency, and accessibility of this system.

Page 13 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

17

After examining check-

clearing activities, the committee concluded that Reserve Banks’

withdrawal from the check collection market would disrupt the system in

the short-run, with little promise of substantial benefit over the longer run.

The committee noted that withdrawing from check clearing could increase

check collection prices to small and remote depository institutions and

could disrupt the migration from paper to electronic payments. Similarly,

the report concluded that having the Reserve Banks remain in the ACH

market would be more conducive to the future efficiency and migration to

electronic payments, including joint efforts with industry participants to

spur innovation in products and increase ACH usage.

In addition to the Reserve Banks, other entities offer payment system

services to financial institutions. To process check payments, financial

institutions can set up direct, individual connections with other financial

institutions with which they can exchange check images for clearing of

checks drawn on the accounts of their respective customers. Institutions

also can submit their checks to clearinghouses that process and transmit

check image files for clearing to the respective clearinghouse members

on which the checks are drawn. For example, in addition to operating the

only other ACH and wire transfer networks that compete with the offerings

of the Federal Reserve, TCH also acts as a clearinghouse for check

images. Other competitors that provide checking services include

correspondent banks, bankers’ banks, and corporate credit unions. The

financial institution customers of these entities will send or receive their

checks, ACH payments, or wire transfers using these entities’ systems,

17

See Committee on the Federal Reserve in the Payments Mechanism, Federal Reserve

System, The Federal Reserve in the Payments Mechanism, (January 1998). This study

excluded cash processing, a service normally expected of a central bank, as well as credit

and debit card processing in which the Reserve Banks play no direct operational role. The

study also excluded other “wholesale” payment services of the Reserve Banks, such as

large-value funds and Fedwire securities transfers.

OtherEntitiesInvolvedin

thePaymentsSystem

which may pass them to other entities, including individual institutions,

TCH, or the Reserve Banks, for processing. Some financial institutions

also use nonfinancial third-party data processors that aggregate

payments for these services and route them to other entities, including

the Reserve Banks or their competitors, for processing.

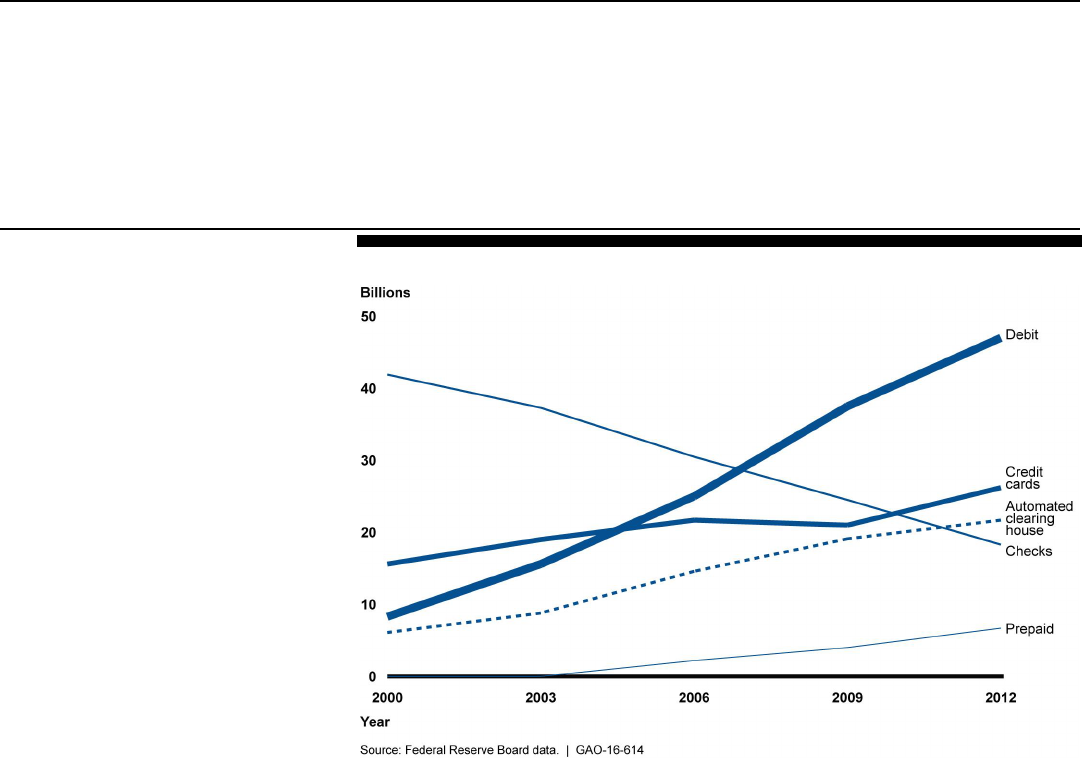

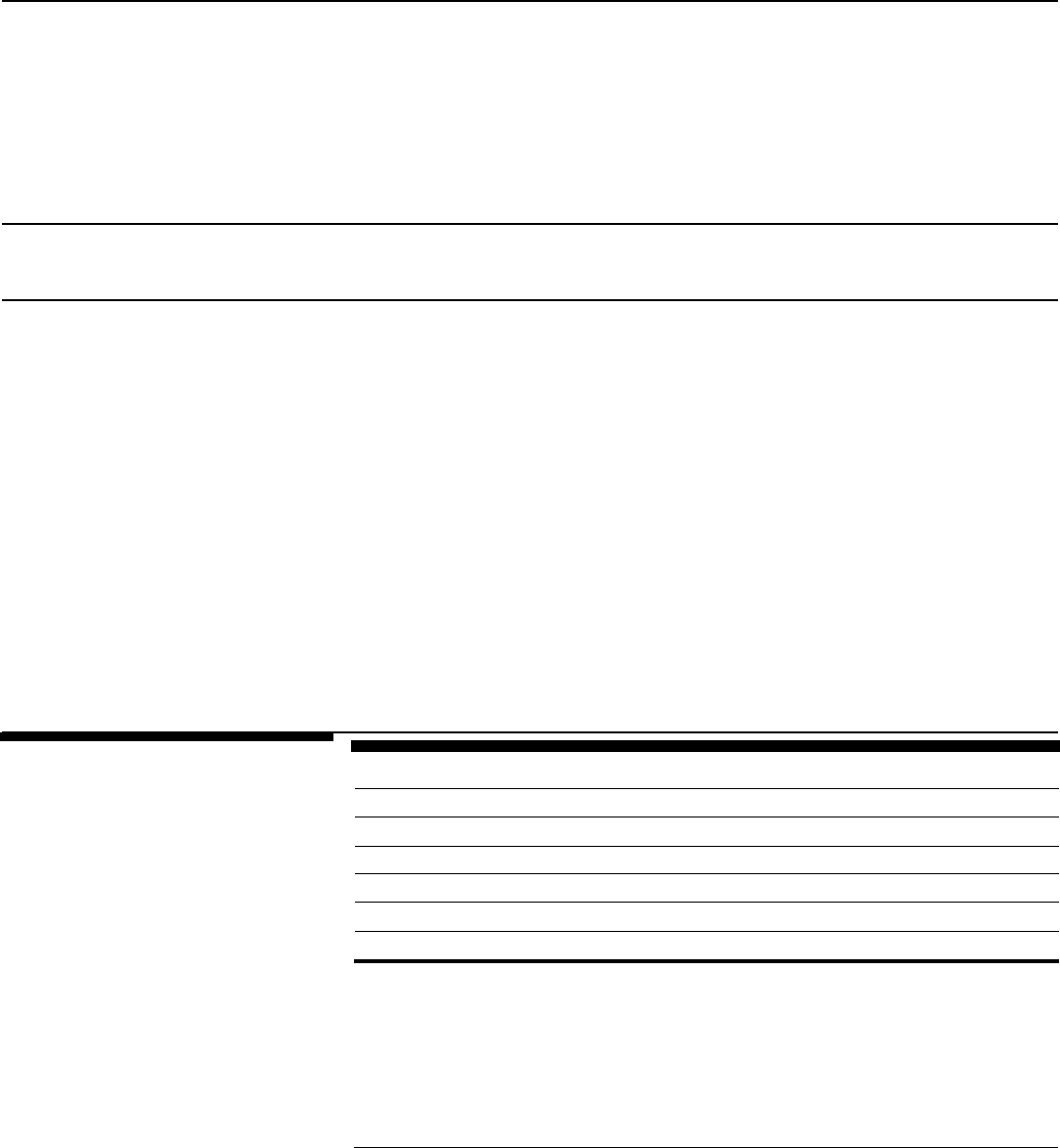

From 2000 through 2012, total noncash payments grew, and check

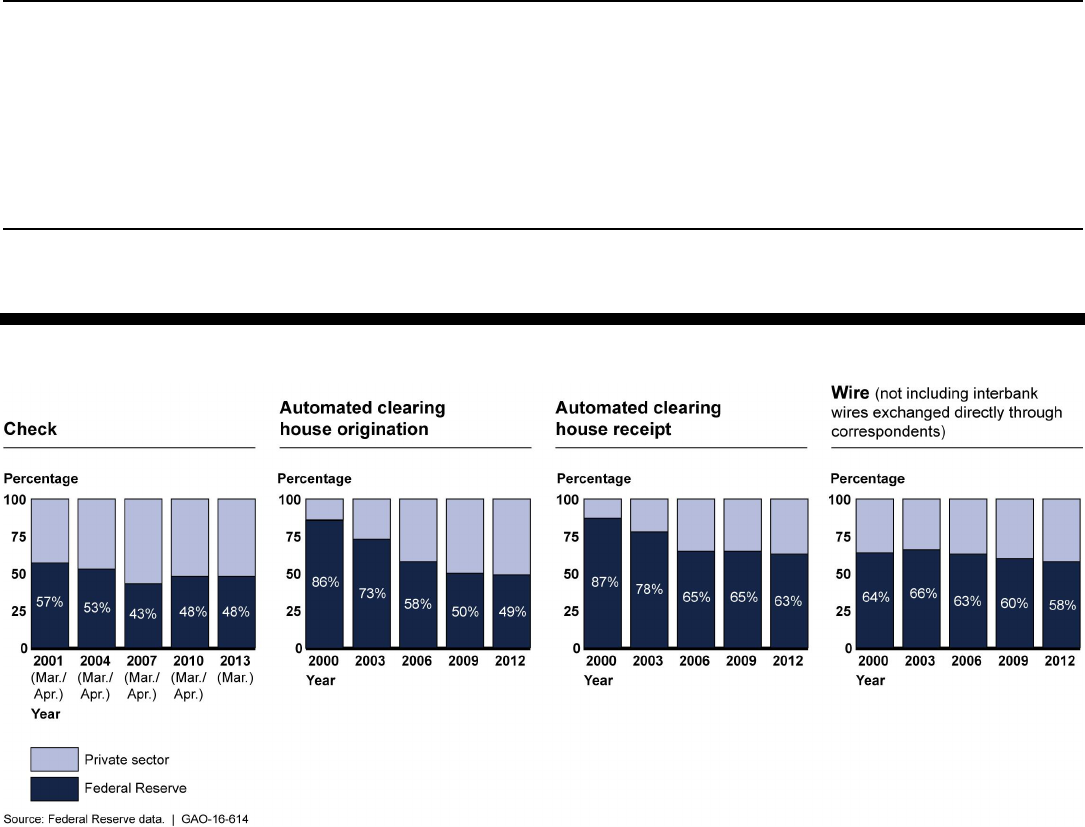

volumes declined, as the use of other payments types increased.

According to data the Federal Reserve reported in 2013, noncash

payments—including those made with debit cards, credit cards, ACH, and

prepaid cards (but excluding wire transfers)—grew almost 69 percent

from 2000 to 2012.

Page 14 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

18

The fastest growing payment method was debit

cards, whose use grew by more than 466 percent over this period. The

number of ACH payments also grew by more than 255 percent, while the

number of check payments declined by more than 56 percent. Figure 4

shows how the use of payment types changed in this period.

18

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, The 2013 Federal Reserve

Payments Study: Recent and Long-Term Trends in the United States: 2000–2012,

detailed report and updated data release (Washington, D.C.: July 2014). This is the

Federal Reserve’s most recent triennial study of payment market trends, which publishes

payment statistics for a single point in time every 3 years.

CheckVolumesDeclineas

UseofOtherPayment

TypesRises

Figure 4: U.S. Noncash Payments by Transaction Type, 2000–2012

Page 15 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

The changes in the relative use of the various payment methods largely

reflect consumers switching from check use to card-based or other

payment methods. According to the Federal Reserve’s analysis,

consumers wrote about 8 billion fewer checks to businesses in 2012 than

they had in 2006, and businesses wrote 4 billion fewer checks in 2012 to

consumers or other businesses than they had in 2006. Federal Reserve

staff noted that although check volumes have declined, the dollar value of

payments made by checks—estimated by the checking industry

association to exceed $20 trillion in 2013—indicates that checks are still

an important payment method in the United States because businesses

continue to use them to make payments to other businesses.

The growth in ACH payments encompassed its increased use for making

various types of payments, including for payroll deposits and automatic

bill payments, as well as increased use by consumers to make one-time

payments over the Internet. Although it had not obtained the volume of

wire transfers as part of past triennial reports, the Federal Reserve

analysis estimated that more than 287 million wire transfers occurred in

2012, with a combined value of about $1,116 trillion. Consumer senders

accounted for just 6 percent of total wire transfers in 2012.

The Federal Reserve Banks incur various costs as part of their provision

of payment services. To fully account for these costs, the Federal

Reserve uses a detailed accounting system for accumulating and

reporting cost, revenue, and volume data for the payment and other

services Reserve Banks conduct. The Federal Reserve’s cost-accounting

practices generally align with those used in the private sector and with

cost-accounting standards for federal entities. As part of setting fees for

its payment services, the Federal Reserve is required to also impute

some additional costs that it would have incurred if it were a private entity.

Although various options could be used to calculate these imputed costs,

each with their own trade-offs or methodological challenges, the current

methodology the Federal Reserve uses appears reasonable. However,

the Federal Reserve is not currently including certain costs that its

private-sector competitors may incur, including costs related to integrated

planning for recovery and orderly wind down of operations. According to

Federal Reserve data from 1996 through 2015, the Federal Reserve

Banks generally recovered the identified costs of providing payment

services, as required by the act. Although the Federal Reserve has

various internal controls to help ensure it accurately captures its payment

services costs, it has not obtained a detailed, independent evaluation of

the reliability of these processes in over three decades.

The Federal Reserve Banks use a detailed cost accounting system that

helps them meet several requirements relating to how to set the fees

charged for payment services and account for and recover the costs

incurred in providing them. The Monetary Control Act requires that over

the long run the Federal Reserve’s fees be established on the basis of all

direct and indirect costs incurred in providing payment services, and an

allocation of imputed costs that would have been incurred by a private-

sector provider. Because the Board must set fees based on the total of

these costs, failure to account for all of its actual costs could result in the

Federal Reserve underpricing its services and competing unfairly with

private-sector providers.

According to data provided to us by the Federal Reserve, the Federal

Reserve Banks incurred over $410 million in actual costs as part of

providing payment services in 2014. These costs include personnel costs,

such as salaries and benefits of employees who perform payment

services activities, as well as those associated with equipment, materials,

supplies, shipping, and other costs for payment services activities.

Additionally, costs associated with overhead and support services

(activities benefitting multiple Reserve Banks, but performed under a

Page 16 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

FederalReserveHas

ProcessesinPlaceto

ComplywithCost

Recovery

Requirements

FederalReserveUsesa

DetailedSystemfor

AccountingfortheFull

CostsAssociatedwithIts

PaymentServices

centralized function) are allocated to the payment services. For example,

expenses associated with functions such as sales and accounting are

categories of support costs for payment services activities. The majority

of the actual costs the Federal Reserve incurs in providing payment

services—78 percent in 2014—are support costs related to activities such

as developing software applications, implementing information security,

and providing help desk services.

The Planning and Control System (PACS) Manual for the Federal

Reserve Banks establishes cost-accounting policies and provides a

uniform reporting structure for accumulating and reporting cost, revenue,

and volume data for the payment and other services conducted by the

Reserve Banks.

Page 17 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

19

This system establishes a set of rules and procedures

used to determine the full cost of these services. Costs are accounted for

at the individual Reserve Bank level and subsequently aggregated to

reflect costs for all payment services throughout the Federal Reserve

System.

Federal Reserve staff told us that the cost-accounting practices in the

PACS manual generally align with practices used in the private sector.

Additionally, based on our analysis, these practices align with cost-

accounting standards developed for federal entities. While generally

accepted accounting standards exist for the preparation of financial

statements, no single set of authoritative or uniform standards have been

developed that apply to the cost accounting practices used in the private

sector. In the private sector, systems like PACS typically are used to

provide management with internal information for making decisions on

cost efficiency and capability.

Although no single or uniform set of standards apply to cost accounting

practices in the private sector, Federal Reserve staff acknowledged that

information from PACS helps them manage their operations similar to the

way in which other organizations use cost accounting information.

19

Cost accounting is the accounting process that aims to capture an entity’s costs of

production by assessing the costs associated with the various inputs and steps of

production as well as fixed costs such as depreciation of capital equipment. While cost

accounting is often used within an entity to aid in decision making, financial accounting

information is what is presented to those outside the organization. Financial accounting is

a different representation of costs and financial performance that includes the entity’s

assets and liabilities.

FederalReserveBanks’

CostAccountingPractices

AlignwithPrivate-Sector

PracticesandFederal

Standards

However, they noted that their cost accounting system is detailed and

granular to ensure that they account for all costs when pricing their

payment services as required. The Board engaged an independent public

accounting firm to conduct an evaluation of its payment services pricing

methodology in 1984. This accounting firm’s evaluation included testing

whether costs incurred by the Reserve Banks were adequately captured

and whether support and overhead costs were appropriately allocated.

This auditor’s report concluded that the Federal Reserve’s accounting

and reporting systems that captured its payment services revenues and

costs were operating effectively. In addition, the accounting firm noted

that its testing confirmed that PACS had adequate controls that were

being followed and ensured that costs were being accurately captured.

Furthermore, representatives of the independent public accounting firm

that conducted the 2014 financial audit of the financial statements of the

Federal Reserve System told us that the Reserve Banks have thorough

and redundant internal controls for financial reporting even in comparison

to many commercial organizations. The representatives of this firm told us

that their audits of the expense categories that appear in the Federal

Reserve’s financial statements had not identified significant problems.

They noted that this likely reflected the Federal Reserve’s thorough

system of controls. However, the representatives of this firm told us that

they had not audited the expenses allocated to the payment services

specifically.

In addition, our analysis indicated that the Federal Reserve’s cost

accounting practices aligned with broad cost accounting standards for

federal entities. The Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board

developed the Statement of Federal Financial Accounting Standards 4:

Managerial Cost Accounting Standards and Concepts (SFFAS 4) to help

federal entities provide reliable and timely information on the full cost of

federal programs. Reserve Banks are not required to comply with these

accounting standards because they are not a government agency but

rather federally chartered corporations. However, to provide one measure

of the quality of the Federal Reserve’s practices, we compared PACS

with the requirements of the cost accounting standard for federal entities.

SFFAS 4 directs government entities to meet five standards for their cost

accounting, and our analysis indicated that the Federal Reserve’s PACS

Page 18 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

addressed each of these.

Page 19 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

20

For example, as prescribed in SFFAS 4,

PACS defines specific responsibility segments and provides the Reserve

Bank a process for accounting for the full costs of their services. Based

on this analysis, we concluded that the design of the Federal Reserve’s

system generally aligned with the elements recommended by the

standard. See appendix II for further details on the Reserve Banks’ cost

accounting practices.

Based on our analysis and discussions with market participants and

financial experts, the methodology the Federal Reserve uses to calculate

imputed payment services costs appears reasonable, but some market

participants noted that alternate methodologies might be more

appropriate. As previously discussed, the Monetary Control Act requires

the Federal Reserve to establish fees on the basis of direct and indirect

costs, including an allocation of imputed costs which takes into account

the taxes that would have been paid and the return on capital that would

have been provided if a private firm had provided the services. The total

of the imputed costs and return on capital is referred to as the private-

sector adjustment factor (PSAF). The Board approves the PSAF annually

as part of its annual process for approving fees for the Reserve Banks’

priced services. The PSAF methodology calculates four additional costs

that a typical private-sector payment services provider would incur: debt

financing costs, equity financing costs (or return on equity), taxes, and

payment services’ share of Federal Reserve Board expenses.

21

See

appendix III for further details on the PSAF methodology.

Over the years, the PSAF has declined significantly, following similar

trends in declining transactions, revenues, and assets associated with the

Federal Reserve Banks’ payment service activities. Following declining

payment services revenues and assets, as well as changes in practices

20

The five standards are (1) accumulating and reporting costs of activities on a regular

basis for management information purposes, (2) establishing responsibility segments to

match costs with outputs, (3) reporting full costs of goods and services, (4) recognizing the

costs of goods and services provided from federal entities, and (5) using appropriate

costing methodologies to accumulate and assign costs to outputs.

21

Federal Reserve officials said that the Board Expenses included in the PSAF are real

expenses that represent the costs associated with the Board’s supervision of the Reserve

Banks’ payment services. They noted that Board expenses are included in the PSAF

because they are not captured in PACS, as that cost accounting system only captures real

costs incurred by the Reserve Banks.

FederalReserve’sCurrent

ProcessforSimulating

Private-SectorCosts

AppearsReasonable,but

DoesNotCurrently

AccountforCertainCosts

among payment services customers, the total imputed costs arising from

the Federal Reserve’s PSAF calculations declined from $150 million in

2002 (or an inflation-adjusted basis of nearly $194 million using 2015

dollars) to $13 million in 2016. However, as a percentage of total payment

services assets, the PSAF increased slightly from 1.3 percent to 1.5

percent during this period. Federal Reserve staff said that they use

publicly available information to calculate the imputed elements of their

PSAF methodology and publish the methodology and its results annually

in the Federal Register. Additionally, all proposed and finalized changes

to the PSAF methodology, as well as a summary of the public comments

on these changes, are published in the Federal Register and posted to

the Federal Reserve’s website. Federal Reserve staff indicated that they

follow this approach to help ensure that the PSAF methodology is

transparent and that its results can be more easily verified by the private

sector.

As part of its attempts to improve its accuracy and conform the PSAF to

changes in the payment system market, Federal Reserve staff noted that

the Board has made numerous changes to the methodology over the

years. The Federal Reserve staff said that they consider changes to the

PSAF methodology when conditions in the marketplace or industry

suggest that practices in the markets or other changes have occurred that

should be considered in the methodology for imputing costs. They said

that in those situations they evaluate different options to improve the

methodology and request public comments on the strongest options

before adopting a new approach. We reviewed the changes made

between 1980 and 2014 and found that the Federal Reserve had publicly

sought comment on significant changes to its PSAF methodology 10

times during this period. These include changes to how the return on

equity is calculated and to the peer group used to approximate the levels

of debt and equity in the model. See appendix III for further details on

changes to the PSAF methodology over time.

Private-sector market participants have criticized the Federal Reserve for

not accounting for or imputing into the PSAF certain regulatory

compliance costs that private-sector providers incur. These costs include

those associated with federal antimoney-laundering requirements,

increased audit and risk management, overseeing the risks posed by

service vendors, and integrated planning for recovery and wind down of

operations. The Federal Reserve has said that it accounts for some of

these costs as actual expenses incurred by the Reserve Banks, and that

it has been considering how the other costs might be incorporated into

the PSAF.

Page 20 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Concerns over Whether All

Relevant Costs Are Included in

the PSAF

In May 2015, the Electronic Check Clearing House Organization

(ECCHO) submitted a letter to the Board expressing concerns over the

Federal Reserve’s failure to account for certain costs being borne by

private-sector check services providers and urged it to conduct a

complete (de novo) competitive impact analysis of the Reserve Banks’

check image services. ECCHO specifically noted that many of its

members that provide check processing services to other institutions

incur costs associated with compliance with federal antimoney-laundering

requirements. In a written response sent in December 2015, the Chair of

the Federal Reserve Board’s Committee on Federal Reserve Bank Affairs

said that if private-sector banks incur material antimoney-laundering

compliance costs related to their check collection services that the

Reserve Banks do not, it might be appropriate for Reserve Banks to

impute such costs as part of the PSAF. However, Federal Reserve staff

said that correspondent banks have informed them that determining the

proportion of antimoney-laundering costs that relate to check services

specifically would be difficult, because they do not allocate compliance

costs directly to this service. Federal Reserve officials said in their

response to ECCHO that, while they did not see the need for the

complete competitive impact analysis that ECCHO requested, they

continue to consider how they could identify ways to incorporate these

costs into the PSAF methodology if they are material. However, until the

Federal Reserve determines and implements such costs into the PSAF,

the imputed costs will not reflect these actual expenses incurred by many

of the Federal Reserve’s competitors.

Additionally, enhanced regulatory standards, including those that apply to

entities designated as systemically important financial market utilities,

have raised regulatory compliance costs for the Federal Reserve’s key

competitor.

Page 21 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

22

Under the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer

Protection Act, entities engaged in payment, clearing, or settlement

activity must be designated as systemically important by the Financial

Stability Oversight Council if the Council determines that the failure of or a

disruption to the functioning of the entity could create, or increase, the risk

of significant liquidity or credit problems spreading among financial

institutions or markets and thereby threaten the stability of the U.S.

22

Financial market utilities are any persons that manage multilateral systems for the

purpose of transferring, clearing, or settling payments, securities, or other financial

transactions among financial institutions or between financial institutions and the persons,

subject to certain exclusions. 12 U.S.C. § 5462(6).

financial system.

Page 22 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

23

Such entities then become subject to heightened

prudential and supervisory provisions intended to promote robust risk

management and safety and soundness. The act required the Federal

Reserve to issue rules to prescribe risk-management standards for those

financial market utilities designated as systemically significant for which

the Board is the supervisory agency. In November 2014, the Board

issued amendments to Regulation HH, based on the international risk-

management standards for payment services that are systemically

important developed by the Committee on Payment and Settlement

Systems (CPSS) and the Technical Committee of the International

Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO).

24

Regulation HH

requires designated financial market utilities to implement rules,

procedures, or operations designed to ensure that the financial market

utility meets or exceeds various standards, including, among others,

those relating to its governance, risk management and credit risk.

25

For

example, the entity must have an integrated plan for its recovery and

orderly wind down, maintain unencumbered liquid financial assets

sufficient to cover the greater of the cost to implement its recovery and

orderly wind-down plans and 6 months of current operating expenses,

and hold equity greater than or equal to the amount of unencumbered

liquid financial assets required.

Representatives from TCH told us that complying with these standards

has increased their regulatory compliance costs and that they question

the extent to which the Federal Reserve has appropriately incorporated

these costs into the PSAF.

26

TCH estimated that their efforts to comply

with these requirements have increased their operating costs by 10

percent, including additional costs associated with their Risk Office that

conducts activities related to information technology security, risk

management, liquidity risk and orderly recovery and wind-down planning,

23

Pub. L. No. 111-203, Tit. VIII, 124 Stat. 1376, 1802 (2010).

24

79 Fed. Reg. 65,543, 65,557 (Nov. 5, 2014) (codified at 12 C.F.R. pt. 234). The

international standards on which the revised Regulation HH was based were the

Principles for Financial Market Infrastructures (PFMI) developed by CPSS and IOSCO in

2012. Effective September 2014, the CPSS changed its name to the Committee on

Payments and Market Infrastructures.

25

12 C.F.R. § 234.3.

26

The Financial Stability Oversight Council designated TCH as a systemically important

financial market utility on the basis of its role as the operator of CHIPS.

among other things. They also said that they incur greater costs

associated with responding to their customers’ due diligence reviews

regarding vendor management, an element of the federal bank

examination process in which federal bank examiners evaluate a financial

institution’s third-party relationships as a component of their overall risk-

management processes.

The Federal Reserve has incorporated some, but not all, of these

expenses into the imputed costs it calculates as part of the PSAF.

Federal Reserve staff have said that although the Reserve Banks’

payment services are not always subject to the same regulatory regime

as similar services provided by the private sector, the Reserve Banks are

subject to Board supervision and that these oversight costs are already

included in the PSAF as Board expenses and are being recovered

through revenue from the services. Additionally, Federal Reserve staff

told us that the Reserve Banks have devoted increased resources to

audit and risk management functions and that costs associated with these

functions—including additional personnel—are captured in PACS as

internal audit costs at the product line level. Federal Reserve staff said

that the amount of these costs had increased in recent years as they

hired additional staff to perform expanded oversight activities.

Additionally, in order to foster competition with private-sector financial

market utilities that are required to hold liquid net assets funded by equity

to manage general business risk, the Federal Reserve Board requires the

Fedwire Funds service to impute equity held as liquid financial assets

equal to 6 months of estimated current operating expenses. To meet this

requirement the Fedwire Funds service imputed an additional $2.7 million

in equity above the $51.1 million it imputed to meet other capital

requirements.

Page 23 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

27

This additional imputed equity, at the equity financing rate

in the 2016 PSAF, resulted in the Federal Reserve having to recover

additional imputed financing costs of $265,000. Federal Reserve staff

also clarified that, as a service provider of last resort, the Fedwire Funds

Service is subject to unique requirements that do not apply to CHIPS. For

example, the staff noted, Reserve Banks have incurred (and continue to

incur) substantial expenses in recent years to develop, implement, and

test manual procedures for settling systemically important transactions in

27

For its imputed PSAF capital structure, the Federal Reserve seeks to have its level of

equity meet the requirements for a well-capitalized institution, which includes the

standards that total capital to risk-weighted assets ratio of at least 10 percent and a

leverage ratio (tier 1 capital to total assets) of at least 5 percent.

the unlikely event that the Fedwire Funds Service automated systems are

not available. Additionally, Federal Reserve staff told us that they also

receive inquiries from customers conducting vendor management due

diligence. Federal bank examiners told us that they have not noticed any

differences in how either the Reserve Banks or TCH respond to questions

from financial institutions on their vendor relationship and that in the

course of an examination they would look at an institution’s relationship

with the Federal Reserve the same way as they would view an

institution’s relationship with TCH.

However, the Federal Reserve has not incurred or imputed costs related

to a plan for recovery and orderly wind down that is required of CHIPS. In

a 2014 request for comment on revisions to its Policy on Payment System

Risk, the Board noted that Fedwire services do not face business risk that

would cause the service to wind down in a disorderly manner and disrupt

the stability of the financial system because the Federal Reserve, as the

central bank, would support a recovery or orderly wind down of the

service, as appropriate, to meet public policy objectives.

Page 24 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

28

As a result,

Federal Reserve staff said, the Board currently does not require the

Fedwire service to develop recovery or orderly wind-down plans or to

estimate or impute the costs of developing those plans. However,

estimating what these costs would be for its own operations if it were a

private firm and including them in its PSAF methodology would enable the

Federal Reserve to more completely impute costs that it would have

incurred as a private firm in order to meet its cost recovery goals.

As previously noted, the Monetary Control Act states that the Federal

Reserve must impute certain costs for its payment services that would

have been incurred if a private firm had provided them. Additionally, the

28

79 Fed. Reg. 2838, 2842 (Jan. 16, 2014). The Federal Reserve’s Policy on Payment

System Risk sets out standards on management of risks of financial market utilities that

are subject to the Federal Reserve’s supervisory authority but are not designated financial

market utilities, including those operated by the Federal Reserve Banks. The policy

applies to public and private-sector systems expected to settle a daily aggregate gross

value of U.S. dollar-denominated transactions exceeding $5 billion on any day during the

next 12 months. These payment systems are required to identify, monitor, and manage

general business risk and hold sufficient liquid net assets funded by equity to cover

general business losses so that it can continue operations and services as a going

concern if those losses materialize. Further, liquid net assets should at all times be

sufficient to ensure a recovery or orderly wind down of critical operations. Designated

financial market utilities subject to the Board’s Regulation HH are not subject to the risk-

management standards set out in the policy.

Reasonableness of

Methodology

act states that the Federal Reserve’s pricing principles shall give due

regard to competitive factors and the provision of an adequate level of

services nationwide. However, the act does not specify exactly how the

Federal Reserve should impute these costs and various ways could

reasonably exist to do so. The Federal Reserve has stated that there is

no perfect private-sector proxy for imputing these costs and that the

PSAF methodology represents a reasonable approximation of the costs,

though some market participants have criticized the methodology.

Nevertheless, some market participants have questioned the

appropriateness of the Federal Reserve’s current PSAF methodology.

Representatives from TCH said that the PSAF should be calculated using

a peer group comprising payments-processing companies. They noted

that in 2015 their company’s equity capital was materially larger than the

imputed equity levels calculated by the Federal Reserve. However,

neither the Board’s rule on risk management standards for systemically

important financial market utilities that it regulates nor the international

framework for addressing risks of financial market utilities on which it was

based dictates any specific equity requirements other than to hold at least

6 months of current operating expenses funded by equity for liquidity

reasons and equity greater than or equal to the amount of liquid net

assets required.

Some have argued that the Federal Reserve’s current approach for

imputing debt and equity into the PSAF—in which it uses financial data

from all U.S. publicly traded firms in Standard and Poor’s Compustat

database—does not sufficiently reflect the financial activities that its

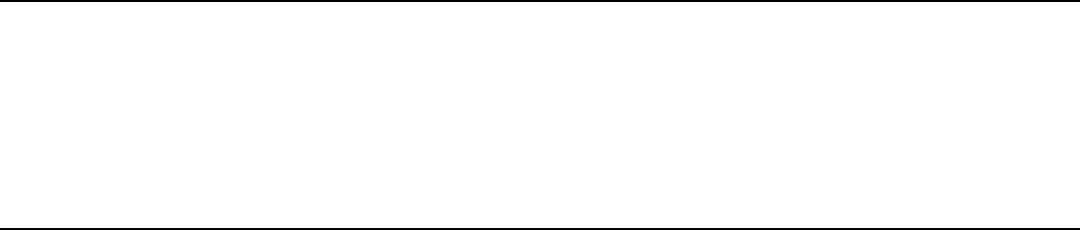

payment services represent. Furthermore, the U.S. publicly traded firm

market includes many firms that are engaged in industries outside of

payment services that may be even less similar to the Federal Reserve

than is TCH. However, Federal Reserve staff said that basing the imputed

debt and equity levels on a peer group consisting of firms providing

payment services, such as large bank holding companies, is not optimal

because such firms engage in many different lines of business and have

risk profiles dissimilar to the payment services provided by the Reserve

Banks. Additionally, the Federal Reserve has noted that a methodology

based on all publicly traded firms decreases the risk of price volatility that

could result from changes in the characteristics or financial results of a

limited peer group. If the Federal Reserve’s product pricing had to vary

widely each year because of large variability in the PSAF, such volatility

could be disruptive to its customers and the payment systems market.

Page 25 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

Furthermore, the PSAF methodology uses data in the public domain to

help ensure that the PSAF calculation is replicable and transparent.

Federal Reserve staff noted that the Monetary Control Act states that all

Reserve Bank services shall be priced explicitly, which the Board

interprets as being fully transparent in their pricing. Many private-sector

payment services providers, including TCH, are not publicly traded and

do not provide publicly available financial information, which, if used to

calculate the PSAF, could hamper the Federal Reserve’s goal of

maintaining the transparency and replicability of its methodology.

Transparency can be an important goal, and our 2000 report included

recommendations that the Federal Reserve implemented to increase the

transparency and involvement of market participants in its pricing

activities.

Page 26 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

29

As noted, the Federal Reserve has attempted to use different

methodologies for calculating the PSAF, including previously using the

financial data from a peer group of bank holding companies to calculate

the PSAF’s target return on equity. Although the Federal Reserve no

longer bases the PSAF methodology’s peer group on the top 50 bank

holding companies, the resulting equity financing rates have remained

similar. We reviewed the return on equities for the top 50 bank holding

companies from 2006 through 2015, and found that the average pre-tax

return on equity was 10.5 percent for these bank holding companies,

which is similar to the 10.1 percent pre-tax return on equity used in the

Federal Reserve’s 2015 PSAF calculation.

Because the PSAF is a proxy for private-sector costs and profit

dependent on a range of variables, and because of the Reserve Banks’

unique structure and operation and the lack of perfectly comparable

private-sector competitors, the calculation of the PSAF amount involves

trade-offs and assumptions that could be reasonably debated. For

example, assumptions on how to impute the return on equity in the

methodology can dramatically affect the overall figure. However, as

previously noted, changing the way the equity is imputed to include

nonpublic financial information might come at the cost of transparency

and replicability of the methodology.

29

See GAO, Federal Reserve System: Mandated Report on Potential Conflicts of Interest

GAO-01-160 (Washington, D.C.: July 19, 2001).

While the Federal Reserve’s approach seems reasonable, any single

PSAF figure calculation could be reasonably criticized based on the

assumptions made and trade-offs chosen. Likewise, different trade-offs

and assumptions could result in higher or lower PSAF figures. We asked

three finance experts to review the Federal Reserve’s PSAF

methodology.

Page 27 GAO-16-614 Payment System Competition

30