CREDIT ENHANCEMENT

FOR GREEN PROJECTS

Promoting credit-enhanced nancing

from multilateral development banks

for green infrastructure nancing

iisd.org

Madhu Aravamuthan

with Marina Ruete

and Carlos Dominguez

May 2015

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects ii

© 2015 The International Institute for Sustainable Development

Published by the International Institute for Sustainable Development.

International Institute for Sustainable Development

The International Institute for Sustainable Development (IISD) contributes to sustainable development by advancing

policy recommendations on international trade and investment, economic policy, climate change and energy, and

management of natural and social capital, as well as the enabling role of communication technologies in these areas.

We report on international negotiations and disseminate knowledge gained through collaborative projects, resulting

in more rigorous research, capacity building in developing countries, better networks spanning the North and the

South, and better global connections among researchers, practitioners, citizens and policy-makers.

IISD’s vision is better living for all—sustainably; its mission is to champion innovation, enabling societies to live

sustainably. IISD is registered as a charitable organization in Canada and has 501(c)(3) status in the United States. IISD

receives core operating support from the Government of Canada, provided through the International Development

Research Centre (IDRC), from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Aairs and from the Province of Manitoba. The

Institute receives project funding from numerous governments inside and outside Canada, United Nations agencies,

foundations and the private sector.

Head Oce

161 Portage Avenue East, 6th Floor, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada R3B 0Y4

Tel: +1 (204) 958-7700 | Fax: +1 (204) 958-7710 | Website: www.iisd.org

Geneva Oce

International Environment House 2, 9 chemin de Balexert, 1219 Châtelaine, Geneva, Switzerland

Tel: +41 22 917-8373 | Fax: +41 22 917-8054 | Website: www.iisd.org

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects

Promoting credit-enhanced financing from multilateral development banks for green infrastructure financing

May 2015

Written by Madhu Aravamuthan with Marina Ruete and Carlos Dominguez

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects iii

Executive Summary/Methodology

This paper seeks to identify, review and understand credit-enhancement schemes provided by multilateral

development banks and international financial institutions. It does this to determine, through the analysis of case

studies, the applicability of such credit-enhancement mechanisms to infrastructure and green infrastructure projects.

This analysis is intended to provide a basic notion of the challenges faced by the various participants in obtaining and

assigning financing for both infrastructure and green projects.

The paper starts by defining its central terms, infrastructure and green infrastructure. This first chapter briefly reviews

the terms to underscore the fact that the diculty in defining them reflects the complex nature of the projects seeking

investment. It then continues with an overview of traditional credit-enhancement schemes, with a more specific look

into the schemes oered by various multilateral development banks. Chapter Three then analyses, through three

examples of successful credit-enhancement schemes for both general and green infrastructure projects, the possible

applications of such schemes for future projects.. The paper concludes with a summary of challenges identified and

goals for the future.

While this paper is based on policy and research, interviews with relevant personnel at multilateral development

banks were extremely helpful in providing a perspective on internal processes, investment goals, green infrastructure

promotion and general practices regarding infrastructure development.

The authors are grateful to the following persons for their time and eorts in providing us valuable input:

• Pradeep Singh, Deputy Dean Indian School of Business; former Vice-Chairman and CEO, Infrastructure

Development Finance Company (Projects) Ltd.

• James Close, Director, Climate Change Group, PPIAF, World Bank

• Matthew Jordan-Tank, Head of infrastructure policy, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development

• Jan van Schoonhoven, Counsellor Infrastructure and Public-Private Partnerships, United Nations Economic

Commission for Europe

• Satheesh Sundararajan, Infrastructure Finance Specialist PPIAF, International Bank for Reconstruction and

Development

• Tomoko Matsukawa, Senior Financial Ocer, Financial Solutions, World Bank

• Vivek Rao, Senior Project Ocer, Asian Development Bank

• María Netto Schneider, Lead Capital Markets and Financial Institutions Specialist, Inter-American

Development Bank

• Malik Faraoun, Principal Investment Ocer, Infrastructure Finance and PPP, African Development Bank

• Martin Berg, Investment Ocer, Climate Change & Environment, New Products & Special Transactions,

European Investment Bank

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects iv

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. Green Infrastructure Financing .........................................................................................................3

Defining Matters .................................................................................................................................................3

Green Infrastructure Financing .......................................................................................................................4

Chapter 2. Credit Enhancement ........................................................................................................................... 7

Multilateral Development Banks – Credit-enhancement schemes ...................................................9

African Development Bank (AfDB) ..................................................................................................... 10

Asian Development Bank (ADB) .......................................................................................................... 11

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) ................................................... 11

European Investment Bank (EIB) ......................................................................................................... 12

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) ..................................................................................... 12

International Finance Corporation (IFC) ............................................................................................ 13

World Bank Group (World Bank, MIGA, IBRD) .............................................................................. 13

Chapter 3. Case Studies on Credit Enhancement ......................................................................................... 15

Successful Credit-Enhancement Projects ................................................................................................. 15

Asian Development Bank: India – IIFCL (2012) .............................................................................. 15

World Bank Group: Nigeria – Power Sector Guarantees Project (2014) ..................................... 17

Inter-American Development Bank: Mexico - Geothermal Project (2014) ..........................18

Chapter 4. Risk Mitigation in Green Infrastructure ....................................................................................... 21

Chapter 5. Conclusions ......................................................................................................................................... 23

References .................................................................................................................................................................. 25

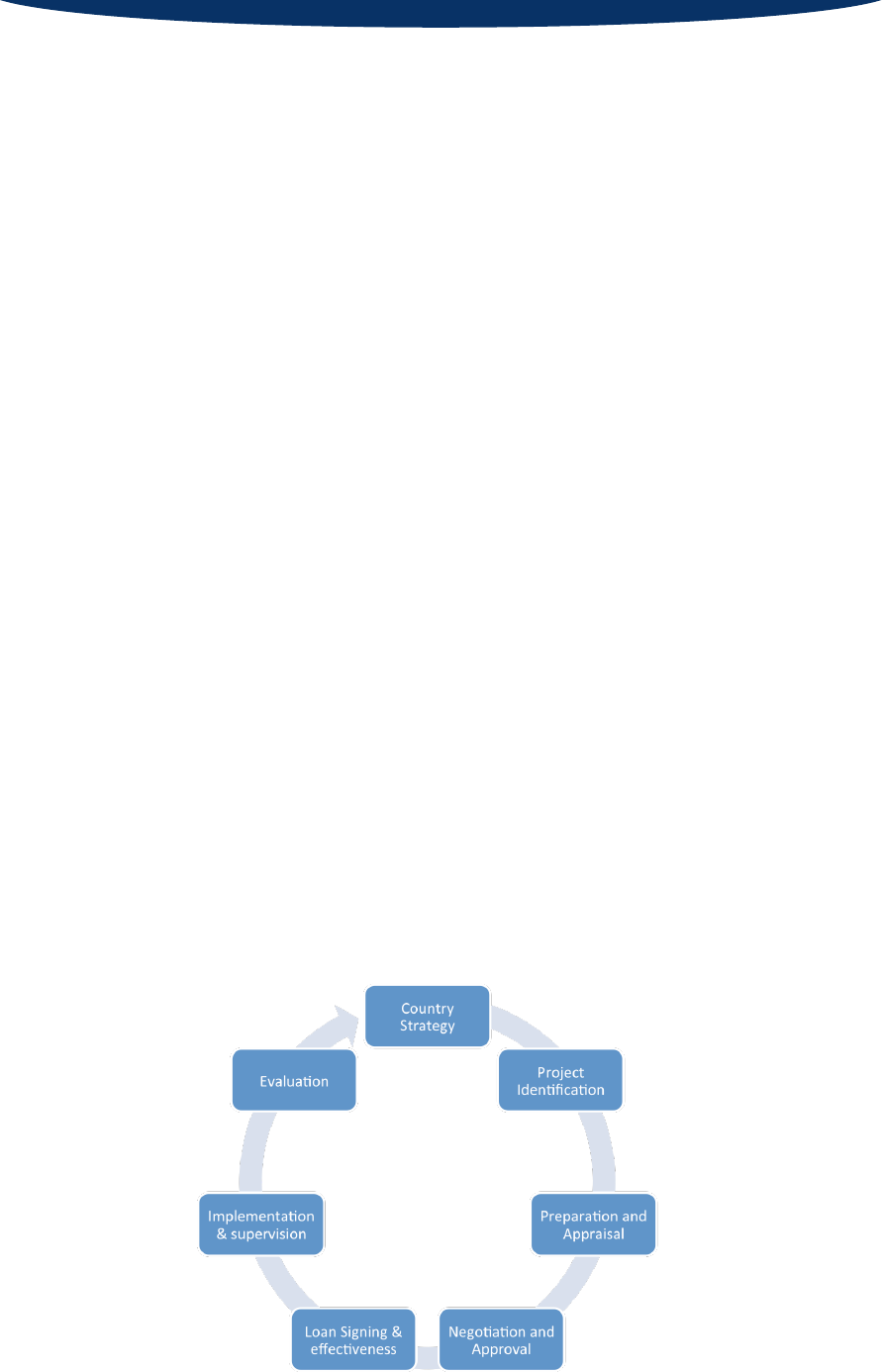

Annex A. Internal Processes at MDBs ..............................................................................................................27

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 1

Introduction

The year 2015 brings important discussions on infrastructure development. The G-20 summit in late 2014 put

infrastructure in the limelight with the setting up of the Global Infrastructure Hub that could help unlock private

infrastructure spending and governments recommitting to help bridge the infrastructure gap. This year is also the

setting of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by the UN General Assembly in which all stakeholders will

participate. Some of these SDGs

1

expressly relate to infrastructure and public–private partnerships, highlighting

their significance in the upcoming years. The World Economic Forum (WEF) in 2015 also focused quite heavily on

infrastructure development benefits and means to achieve the same with increased private investment.

This paper looks at infrastructure development from a definite angle. We review and consider the credit-enhancement

schemes provided by multilateral development banks (MDBs) and international financial institutions (IFIs). While

infrastructure as a whole is a concern, this paper examines it with a view to promoting credit-enhanced financing

from such institutions for green infrastructure projects. With increasing climate challenges and need for infrastructure

development, it is necessary for countries to embrace growth in terms of green projects. This focus is borne out of

a need to mainstream green infrastructure developments and provide them greater access to the sizeable private

funding available. The usually accessible sources of financing, such as debt financing (commercial loans or bonds) or

government support (subsidies) are insucient to meet the global target for infrastructure investment and particularly

green infrastructure. This is exacerbated by the reality that green infrastructure presents dierent and new risks

(and the perception that its risks are more plentiful and severe) that need to be mitigated. Credit-enhancement

instruments are facilitators of access to private funding—they raise the credit standing of projects, enabling them to

attract various other sources of financing.

The issue of leveraging private financing for infrastructure was also raised at the WEF, where a dedicated solution

was mooted—a special entity capitalized by donor countries, private banks and IFIs that would provide partial

guarantees to cover risks in projects. This is an excellent proposition, which, if implemented, would address several

financing concerns. However, at present, it is important to maximize the available sources of financing and credit

enhancement. This is especially important in an era where the funding of green infrastructure projects is being

thoroughly scrutinized. Attracting new and sizeable investment to finance green projects is a dicult proposition, but

one that can be achieved through understanding and application of existing and new methods of financing.

This paper provides an overview of the mechanisms available under credit-enhancement schemes provided by MDBs

and IFIs in order to understand how they can be used to garner greater private sector investment. While a variety of

credit-enhancement products have been floated by MDBs and IFIs, they are not deployed to a large extent due to

several factors. A brief review of successfully credit-enhanced projects presents anecdotal evidence and potential

for future projects in mitigating risk and obtaining private financing. Greater progress can be achieved with a more

eective utilization of these instruments through innovative combinations, knowledge dissemination and entrenched

partnerships between MDBs, project developers, private banks and governments.

1

The SDGs have been built upon to further the Millennium Development Goals and specifically refer to infrastructure development in Goals

7, 9 and 11.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 2

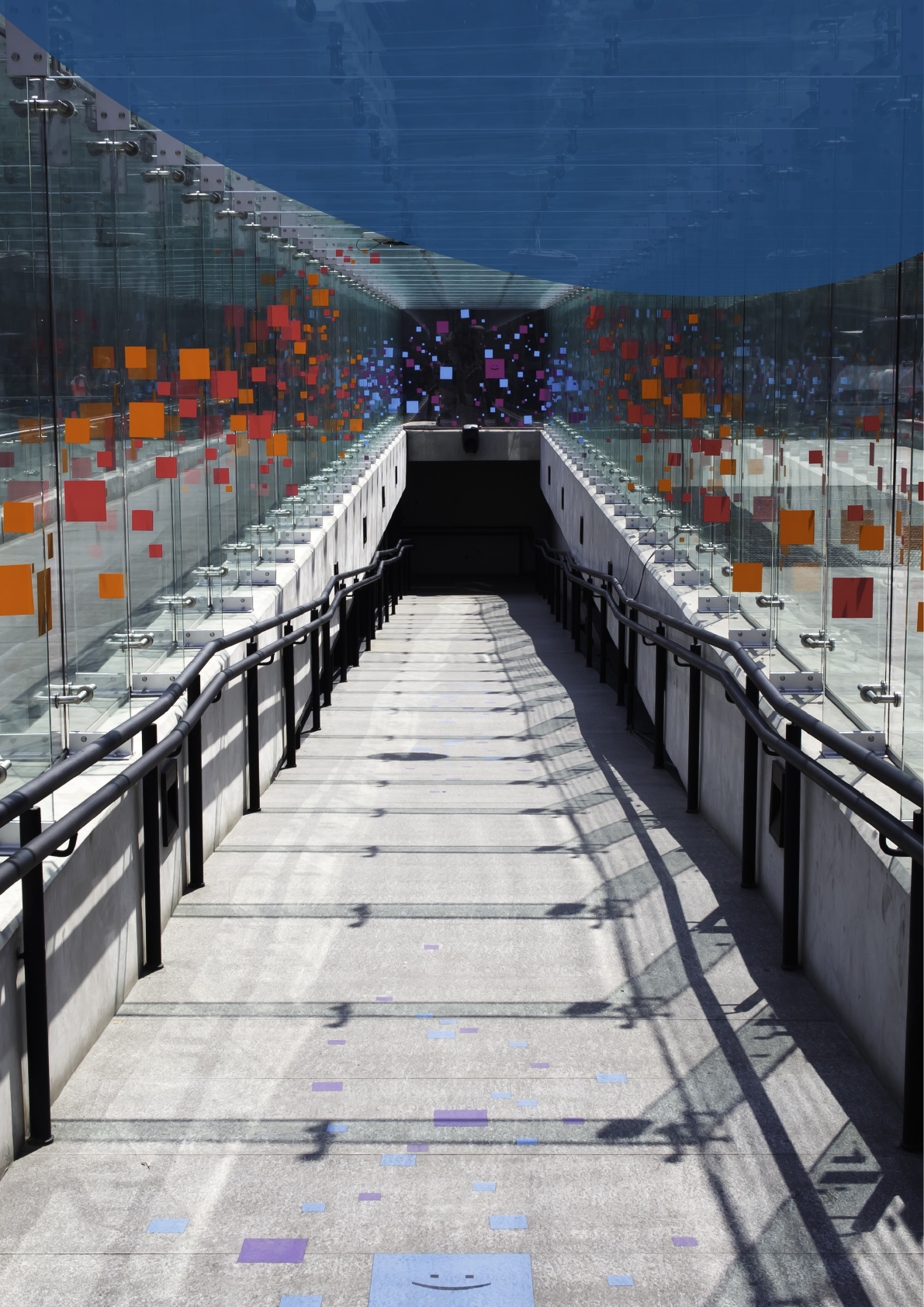

CHAPTER 1.

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

FINANCING

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 3

Chapter 1. Green Infrastructure Financing

Dening Matters

Governments have benefited from private sector involvement in infrastructure projects boosting many times the

number of available resources and, hence, of projects. The large investment associated with infrastructure projects

has both daunted and lured investors at the same time.

While defining infrastructure is a complex endeavour, it can generally be construed as including “facilities, structures,

equipment, or similar physical assets – and the enterprises that employ them”.

2

The term “infrastructure” alone lends

itself to circumstantial definition by determining whether or not a specific structure will be developed on the basis of

its characteristics. It could refer to both physical

3

and social infrastructure

4

together when referring to government

responsibilities but independently when considering potential investment opportunities. For the purposes of this

paper, the term “infrastructure” refers only to physical structures and not social infrastructure.

The size of infrastructure projects and the large investments that they entail make them inherently complex and

beset with hurdles for investors, financiers, governments and the many stakeholders the structure allows. Risk

assessments, coordination of roles, visualization of the implementation phase, and other legal, administrative

and political problems scare investors and financers away from these projects. Over the last couple of decades,

myriad innovative financial models have appeared tailor-made for the actors´ needs or conditions, sectors, type of

infrastructure, country or region particularities, among others.

While it is imperative to provide a comprehensive definition of the term “green infrastructure” in order to develop a case

for extensive credit-enhancement mechanisms among other financing methods, it is also important to understand

the evolving and competitive nature of such a definition. The definition of green infrastructure also varies on the basis

of context and depends on several dierent factors—some of the more obvious are the institutional or academic

purpose, the intended audience or the results expected, or whether it is an investment or ecological discussion. It is

imperative for green infrastructure to develop to accommodate the changes and challenges arising out of new green

technological advancements, which in turn evolve from a greater understanding of the environmental concerns and

issues. A narrow definition of “green” risks excluding such new creations, while one that is too broad might not

be purposeful. The OECD, in its stocktaking exercise on what constitutes green investments, reviews the types of

definitions and their features to suggest that an “open and dynamic approach” and a “competition of definitions and

standards” may be a more productive strategy (Inderst, Kaminker, & Stewart, 2012, p. 7).

A non-exclusive list of infrastructure considered “green” for the purpose of this paper, includes:

(1) Low-carbon energy or energy-ecient infrastructure: Infrastructure that includes processes that produce

climate benefits.

(2) Renewable energy projects: generation or derivation of “energy from natural processes (e.g. sunlight and

wind) that are replenished at a faster rate than they are consumed. Solar, wind, geothermal, hydro and some

forms of biomass are common sources of renewable energy” (International Energy Agency, 2015).

(3) Green buildings: “Green building is the practice of creating structures and using processes that are

environmentally responsible and resource-ecient throughout a building’s life cycle from siting to

design, construction, operation, maintenance, renovation and deconstruction. This practice expands and

2

A Harvard Law School study by Larry Beeferman and Allan Wain (2013), reviews the origin and contexts of the term “infrastructure”

to provide a comprehensive definition: “Facilities, structures, equipment, or similar physical assets—and the enterprises that employ

them—that are vitally important, if not absolutely essential, to people having the capabilities to thrive as individuals and participate in

social, economic, political, civic or communal, household or familial, and other roles in ways critical to their own well-being and that of their

society, and the material and other conditions which enable them to exercise those capabilities to the fullest.”

3

The physical and organizational structures that form the backbone of any nation such as roads, dams, and power plants. Also see

Beeferman and Wain (2013).

4

Social infrastructure includes provision of social services such as health care, education, emergency services and cultural establishments.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 4

complements the classical building design concerns of economy, utility, durability, and comfort. Green

building is also known as a sustainable or high performance building” (Environmental Protection Agency,

n.d.).

(4) Modified green: The addition, modification or updating of existing structures to convert them from

conventional or brownfield infrastructure to include features of green building.

Green Infrastructure Financing

Global procurement trends are pushing the private sector to invest and finance in environmentally friendly products

and services. Infrastructure needs to follow suit. Certain studies estimate that green infrastructure requires between

US$36–42 trillion in investments between 2012 and 2030 or 2 per cent of global GDP per year (Kaminker, Kawanishi,

Stewart, Caldecott, & Howarth, 2013).

However, when adding this “green” characteristic to infrastructure finance, the already complicated nature of project

finance is intensified. Some of the reasons why it is dicult to mobilize capital into these projects is that most

government agents lack of knowledge about the risks and are unfamiliar with the gains of “greening” infrastructure.

Partnerships among governments, investors, financial institutions, civil society and international organisations are

crucial for accelerating green infrastructure growth. However, there is a need for forward-thinking action plans to

allocate the best knowledge, role and risk to each partner in order to increase value for money of green infrastructure

projects.

Globally, public–private partnerships (PPP) are the most preferred method of sourcing private investment for

infrastructure projects, though there are certain very specific methods and innovative initiatives when it comes to

green infrastructure financing. According to the OECD (Kaminker et al., 2013) the dierent financing structures

attracted by green infrastructure include:

• Indirect corporate investments such as corporate bonds, publicly listed equity and mezzanine finance.

• Semi-direct venture capital/private equity funds investing in green companies or straight into projects and

asset-backed securities.

• Direct investment into green infrastructure projects through equity, debt or PPPs.

The systemic requirements of green infrastructure financing are often met through focused project or infrastructure

development funds and viability gap funds.

5

From green infrastructure bonds

6

to PACE bonds,

7

capital markets have

participated in several new formats of raising funds for green infrastructure development. Bloomberg New Energy

Finance (BNEF) has identified that a record US$38 billion was invested in green bonds in the year 2014 alone; with

both institutional (World Bank) and corporate bond issuers (Unilever, GDF Suez) stepping up their oerings (BNEF,

2015).

Participants in green infrastructure finance have diversified their investor base, with governments of developing

countries seeking to green their infrastructure growth with inventive programs and partnerships. For example,

India’s National Solar Mission is an example of green infrastructure being given top priority notwithstanding political

changes; national interests are pushing Kenya’s Climate Change Action Plan towards greener infrastructure and

Brazil’s sustainable climate-smart agriculture programs have been promoted heavily over the past few years (World

Economic Forum, 2012; African Development Bank, 2011; Kaminker, Kawanishi, Stewart, Caldecott, & Howarth,

2013). The increased involvement of governments in promoting green growth has also lead to the formation of new

and interesting structures for project developers to work with governments, MDBs and private investors. MDBs, for

5

For a brief explanation of project development funds and viability gap funds, please see Box C in Chapter 2 below.

6

The popularity of green bonds can be seen in its spread to developing markets. For instance, India launched its very first green

infrastructure bond recently (“Yes Bank,” February 2015).

7

Property Assessed Clean Energy (PACE) is a means of financing energy efficiency upgrades or installing renewable energy for existing

buildings. For instance, the state of California launched the largest clean energy PACE program in the United States (September 2014)

(Gerdes, 2012).

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 5

their part, have greater interest in investing in projects that are considered green or climate friendly, as defined by

their internal processes. For instance, the Inter-American Development Bank (IADB) dedicates at least 25 per cent

of its investment capital towards those projects that have a “climate positive impact” and the European Investment

Bank (EIB) also has the same target of 25 per cent for projects considered green.

8

These new structures entail the participation of many actors with dierent roles in risk taking. Pension funds, for

example, which account for large amounts of capital, may be mandated to invest in green projects. Other private

investors may have capital limits on the amount they invest in projects that do not receive top credit grading.

However, green infrastructure poses high risks given its uncertainties. Governments are usually unable to bear all

risks associated with such large infrastructure projects. It is then key for an enabling actor to be present in order to

ameliorate certain risks and thus improve the standing of the project. This will in turn provide confidence to other

investors about the project and the returns it is capable of producing. National and multilateral development banks

have appeared on the scene as such credit enhancers of infrastructure projects, and particularly green infrastructure.

While there are dierences in the present and perceived risks in regular infrastructure projects and green infrastructure

projects, the internal processes at MDBs for risk assessment and financing these projects is quite the same or mostly

similar.

8

Information gathered from interviews with personnel at the IADB and the EIB.

TEXT BOX A. DIFFERENT DEFINITIONS OF “GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE” BY DIFFERENT ACTORS

Academy

An interconnected network of natural areas and other open spaces that conserves natural ecosystem values and

functions, sustains clean air and water, and provides a wide array of benefits to people and wildlife.

Source: Benedict & McMahon (2006).

International Institutions

Creating more sustainable economies and communities by emphasizing that policies that favor environmentally

sustainable growth should have a more prominent role in development criteria and plans.

Baietti, Shlyakhtenko, Rocca & Patel (2012).

A “competition of definition and standards” has the benefit of making productive use of the full breadth of knowledge

available. It may beneficial for climate change-related investing across the full range of opportunities, ranging from for

new funds for innovative ventures to moving the traditional economy into a greener direction.

There is a sizeable common intersection of the various definitions in terms of sectors (e.g., renewable energy), goods

(e.g., lead-free fuel), services (e.g., water and waste management), technologies and processes (e.g., to enhance energy

eciency).

Regional and National Organizations

A strategically planned network of natural and semi-natural areas with other environmental features designed and

managed to deliver a wide range of ecosystem services. It incorporates green spaces (or blue if aquatic ecosystems are

concerned) and other physical features in terrestrial (including coastal) and marine areas. On land, GI is present in rural

and urban settings.

Source: European Commission, (2013), p. 3.

Green infrastructure is an approach to wet weather management that uses soils and vegetation to utilise, enhance and/

or mimic the natural hydrologic cycle processes of infiltration, evapotranspiration and reuse.

Source: US Environmental Protection Agency (2008).

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 6

CHAPTER 2.

CREDIT ENHANCEMENT

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 7

Chapter 2. Credit Enhancement

This chapter provides an introduction to dierent types of credit-enhancement mechanisms and a brief overview of

those oered by MDBs. In order to understand the need for credit enhancement, it is first essential to review both the

reasons for it and the risks inherent in infrastructure projects.

There has been increasing demand for infrastructure development over the past few decades, with an increased focus

on commensurate economic growth. With this demand came the requirement for innovative financing solutions for

infrastructure projects, especially in developing countries. Also, developing countries present a financing gap, which

has been widened as a result of the financial crisis and new banking regulations (Basel II and Basel III).

Infrastructure projects present a less-attractive option than other long-term projects. There are usually significant

upfront costs involved (that may be even greater in green infrastructure) that are dicult to match with the project’s

cash flow over its life cycle as well as infrastructure-specific risks that are dicult to mitigate. Infrastructure projects

also pose particularized risks that could dier depending on the borrower or investor. For MDBs and development

financial institutions, the main risks arise from lending to sovereign and sub-sovereign entities. These could range

from (a) political risks (regulatory risk, permits and permissions risk, expropriation risk, market-distortion/corruption

risk),

9

(b) credit risk (tari risk, cash flow risk, interest rate risk), (c) environmental risk (d) technical/technological

risk (especially new technology risk for green infrastructure) and other forms of risk. The degrees of influence of these

risks is inherent based on:

(1) The type of borrower (sovereign or sub-sovereign entity, SPV).

(2) Nature of the project (contracts—such as Build-Operate-Transfer or “BOT,” limited recourse, revenue based

lending—sectoral dierences between roads, power, green infrastructure that cause technical and physical

risks).

(3) The issues in the country where it is deployed (some developing countries have specific issues such as

political uncertainty, lack of a developed financial market, etc.).

In addition to the risks set out above, green infrastructure projects face specific challenges. A recent CPI paper looks

at the classification of green investment risks perceptions, noting that when it comes to green infrastructure, the

political risks are amplified due to the increased reliance on public support; technological risks are complicated by the

overwhelming presence of new, cutting-edge technology that is untested in markets to inspire sucient confidence;

and the long payback periods combined with high upfront costs increase the market and commercial risks (Frisari,

Herve´-Mignucci, Micale, Mazza, 2013).

Credit-enhancement schemes respond to the demand to mitigate the risks of the project and attract further financing

and investment to the project. It is an external mechanism that seeks to increase the credit rating/credit worthiness

of the financeable aspects of an infrastructure project. The main objective of a credit-enhancement mechanism is

to ameliorate the credit quality of infrastructure projects that have already achieved a certain minimum threshold,

in order to attract more private financing for the project. The various mechanisms typically employed by multilateral

banks and development financial institutions are detailed in Boxes B and C below.

9

A recent report (WEF, 2015) by the World Economic Forum analyses the various types of political and regulatory risks in infrastructure

projects and methods for their mitigation. The report looks at the risk landscape in different phases of the project (planning/ construction,

operation and termination) and identifies political and regulatory challenges that need to be mitigated, such as the risk of cancellation or

change of scope of project, environmental permits, local community opposition, expropriation, breach of contract, regulatory changes,

taxation changes, judicial and corruption risks.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 8

TEXT BOX B. GUARANTEES AS CREDIT-ENHANCEMENT MECHANISMS

Guarantees are used in project finance to stabilize financing and reassure the lenders and investors they will be repaid.

Guarantees usually have easy triggering methods in case of default. As credit-enhancement mechanisms, the dierent

types of guarantees available seek to cover a specific risk or portion of the debt.

Partial Credit Guarantee (PCG)

A partial credit guarantee is created to absorb part or all the debt service default risk of an infrastructure project,

irrespective of the cause of default. This is particularly helpful to improve a project’s credit profile, enabling it to garner

a wider array of investors and better terms for the debt agreement.

PCGs can be used for any commercial debt instrument (loans, bonds) from a private lender. The existence or proposed

implementation of a PCG is indicative of confidence in the product being floated by the government and can even assist

in bringing new lenders to the table.

Political Risk Guarantee (a.k.a. Partial Risk Guarantee) (PRG)

PRGs cover private lenders and investors for certain risks of lending to sovereign or sub-sovereign borrowers. Thus, by

definition, a PRG necessarily needs to include private participation in the project.

A PRG can cover a number of sovereign or sub-sovereign risks such as currency inconvertibility, political force majeure

such as war, regulatory risk and government payment obligations (such as taris). PRGs are used quite often and

favourably in green energy/energy eciency projects.

TEXT BOX C. OTHER CREDIT ENHANCEMENT MECHANISMS

First-loss provisions

First-loss provisions refer to any device designed to protect investors from the loss of capital that is exposed first if

there is a financial loss of security. These could be debt, equity or derivatives instruments such as cash facilities or

guarantees. They could also take the form of monoline insurances that insure debt security providers who are liable to

pay compensation to the investors, irrespective of the cause of the loss. This helps by shielding investors from a defined

initial amount of losses, thereby improving the creditworthiness of an investment.

Contingent loans

Contingent loans are often used in project finance to backstop the main debt by providing a payment option for specific

case scenarios (for instance, in case of a failure of the government to obtain quality cash flows, the contingent loan is

triggered and investors paid). This mechanism is extremely helpful, especially since the provision of a loan contingent

on the risks that private investors would not want to take on creates a more conducive atmosphere for government

projects to be invested in.

Viability gap funding (VGF)

VGF is used specifically and heavily in infrastructure to cover for the heavy upfront funding that is required to kick start

projects. An analysis of the viability of a proposed project points out the weak areas that prevent large-scale funding

from being obtained. A VGF scheme can be implemented through capital grants, subordinated loans or even interest

subsidies to target specific issues that are aecting the viability of the project. For instance, if the long-term acquisition

of tolls from the project is a deterring risk, then a grant or guarantee from the government in the PPP road project

increases the viability of the project to obtain private investment.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 9

Some infrastructure finance specialists also include A/B loans or grants in the definition of credit-enhancement

mechanisms. Under the A/B loans programs, MDBs oer the “A” portion of the loan while attracting other lenders to

join in a second (or “B”) tranche. The MDB will be the lender-of-record, lead lender and administrative agent in the

transaction. The benefit to the additional lenders (the “B” lenders) is that it reduces part of the risks of the operations,

by also being covered by the “umbrella” of the MDBs that include a preferred creditor status and de jure immunity

from taxation.

Often, these mechanisms are used in combination (with each other or other financing schemes) to achieve a more

eective project. For instance, for Chilean toll road construction, the IADB provided a blend of financial guarantee and

an A/B financing in bond transactions. The resultant guarantor-of-record structure extended the preferred creditor

status to monoline insurers thereby giving risk protection that allowed private insurers to enter the market. Similarly,

to support a pipeline project in West Africa, the World Bank oered a partial risk guarantee while the Multilateral

Investment Guarantee Agency (MIGA) oered political risk insurance that would cover payments owed by the

government (Matsukawa & Habeck, 2007).

Another example of credit-enhancement mechanisms being used in conjunction with other structures is the Global

Energy Eciency and Renewable Energy Fund (GEEREF) launched by the EIB, which includes a first-loss provision

by donors to cushion risk absorption for senior lenders and private investors. This system uses credit-enhancement

techniques within detailed equity structures to achieve greater coverage of potential projects.

The purpose of credit-enhancement schemes is to identify the weaknesses in the financial viability of a project and

improve them to make it more attractive to investors and financers. Private debt finance sources usually come from

bond investors (e.g., pension funds, insurance investors, private debt funds) and commercial banks. Such private

financiers are look for investment-grade rated projects, which means that high-risk projects (including infrastructure

projects) are not of interest to them. The participation of the private sector is key for the viability of infrastructure

projects. Without the assistance provided by credit-enhancement mechanisms, many projects remain unfeasible

and unable to garner private financing. The weakening of the global economy with increased austerity measures and

decreased investment capacity, new banking regulations under Basel II and Basel III, and the perception of high-risk

in infrastructure projects have kept private investors away, especially in developing countries.

10

Unlike direct lending, credit-enhancement schemes: (1) may improve credit rating and/or interest rates of the project;

(2) may raise the profile of the project by boosting confidence in the creditworthiness of the project. Both these

characteristics further the chances of future investments. These benefits are crucial in their ability to mainstream

financing and investors into infrastructure projects.

Multilateral Development Banks – Credit-enhancement schemes

MDBs have traditionally deployed funds in the form of loans, investment or capacity building. The years of experience

and knowledge of the demands in countries have opened their field of work to other financial products, including

credit-enhancement products, which have increased over the last decade.

The World Economic Forum recommended in 2006 that MDBs activities “should shift over time from direct lending

to facilitating the mobilization of resources from the world´s largest private saving pools—international or domestic—

for development-oriented investments through . . . wider use of risk mitigation instruments to alleviate part of the

risk faced by investors (World Economic Forum, 2006). This focus has not shifted completely, but MDBs are oering

credit-enhancement mechanisms as part of the portfolio of products to their member countries.

10

The main concerns for infrastructure financing arising from Basel III are due to the requirements under the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, the

Net Stable Funding Rule and the treatment of interest rate swaps. These three issues are especially potent for green and energy efficient

projects (such as renewable energy projects) that involve high up-front costs, are structured through SPVs and necessitate long pay-out

periods.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 10

When an infrastructure project proposal is put forth to an MDB, its chances of success are increased if it identifies

specific substantial risks that could benefit from credit-enhanced lending. For instance, if a power plant project suers

from a significant risk of continuing subsidies, the project proposal should identify this risk. This proposal could then

have a greater likelihood of obtaining a PRG or a PCG to cover the subsidy risk to make the project more financially

attractive.

Also, in the case of green infrastructure, MDBs skills and capabilities are used to provide confidence to the private

sector. Its participation “raise and deliver concessional climate financing at a significant scale to unleash the potential

of the public and private sectors to achieve meaningful reductions of carbon emissions and greater climate resilience”

(Climate Investment Funds, 2008b). Once MDBs oer credit enhancement for a project, it demonstrates to other

market investors that the project is viable and thereby catalyzes private sector investment. This has been the case

of a wind energy project in Oaxaca, Mexico where IADB, IFC and Clean Technology Fund (CTF) funds were used

to overcome the barriers to investment of the private sector leveraging over US$500,000 of commercial resources

(Climate Investment Funds, 2014). The involvement of MDBs in mitigating certain risks definitely boosts investor

confidence. MDBs have the advantage of experience, reliability, credibility, knowledge of local markets and their

proven track record of supporting long-term investments

It must be noted here that despite dierent risks present and perceived in regular and green infrastructure projects,

MDBs mostly carry out the same risk assessment for both. In fact, the internal procedures for assessing credit-

enhancement proposals and requests for direct loans are also similar.

11

In order for this recognition and implementation to occur, it is important that developing countries are aware of the

various options available to them. The following subsections describe some of the mechanisms and initiatives MDBs

have developed in order to enhance financing in infrastructure.

African Development Bank (AfDB)

The estimated infrastructure spending need in Africa to close the infrastructure gap with other developing countries is

US$93 billion a year (15 per cent of the region’s GDP) for the decade from 2010–2020. Existing ocial development

finance will not be enough to cover the current financing gap needs. It is necessary that it be filled by private investment

(African Development Bank, 2013) and, hence, it is essential to create new mechanisms to attract investors. Over

the past decade, the AfDB’s lending environment became more responsive to the changing needs of the borrower

countries to provide them flexibility and choice. The introduction of guarantees by the AfDB in 2004 opened up new

opportunities for borrowers who could then access lending from third parties, including local commercial banks.

Guarantees

The AfDB has successfully implemented PCGs and PRGs in various African projects through the African Development

Fund’s initiatives over the past two years. A significant example of these eorts is the PRG provided to coal-based

independent power plants in Nigeria, enabling local private investors to come into the projects (AllAfrica, 2014).

Risk-Mitigation Initiative

In 2012, the AfDB introduced the Initiative for Risk Mitigation in Africa (IRMA), recognizing that projects in various

African countries are in dire need of specific assistance and intending to encourage the eective use of the AfDB’s

existing and proposed risk-mitigation services. IRMA has identified various types of risks, including political risk,

credit risk, project development risk, foreign exchange risk, etc.) and correlated them with instruments oered locally

and globally to counter them.

11

This information was gleaned from interviews with officials at major MDBs such as the World Bank, ADB, AfDB, IADB, EBRD and the EIB.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 11

The survey conducted by the IRMA has been helpful in recording results demonstrating that there is a continued

perception of unacceptable levels of risk across African countries that does not match the increased demand for

investment. The survey and paper then helpfully identify next-step solutions for addressing risk-mitigation gaps.

These include increased eectiveness of existing public sector risk-mitigation mechanisms (through marketing,

dedicated product specialists and integrating the programs into the country fabric) and increased participation in

programs initiated by various development finance institutions.

Project Bonds

In the trend of the Project Bond Credit Enhancement (PBCE) scheme introduced by the European Investment Bank

(see below), the AfDB sees the value in supporting project bonds. The promoters of the “Africa 50 Fund” established

in 2013, intends to establish two arms, project development and project finance. The latter is intended to focus on

delivering, among others, credit-enhancement and other risk-mitigation mechanisms similar to that of the PBCE

floated by the EIB.

Asian Development Bank (ADB)

In order to try and address the massive US$8 trillion infrastructure gap for 2010–2020, the ADB has identified and

floated several dierent types of credit-enhancement products. While the first guarantee was issued by the ADB in

1988, the products have evolved and become more sophisticated over the years. In 2006, the Asian Development

Bank re-launched its credit-enhancement products policy with the aim of attracting more potential users. These

products were now more flexible and had a broader application (Asian Development Bank, 2011). Generally, they can

be classified into guarantees to cover credit and political risks of debt instruments and syndications to reduce credit

exposure by transferring some of the risk to financing partners. A majority of the guarantees issued by the ADB cover

borrowing in local currency, which facilitates local financing where full direct loans are impractical.

Guarantees

The ADB typically oers guarantees including PRGs and PCGs. In 2012 the ADB supported infrastructure project

bonds in India by providing a backstop guarantee facility of up to 50 per cent of the India Infrastructure Finance

Corporation Limited (IIFCL)’s underlying project risk to cover four to five projects in the pilot phase of the scheme

(Asian Development Bank, 2012).

Syndications

What ADB defines as Complementary Financing Scheme is “a form of loan syndication whereby ADB acts as

lender-of-record (LOR) but sub-participates the loan to one or more banks that are providing the financing” (Asian

Development Bank, 2006). The ADB also acts as Guarantor-of-Record where it “fronts” a guarantee contract for the

entire amount of the guarantee and then transfers all the exposure to one or more insurers who end up underwriting

the risk in the project. The ADB also presents credit-enhancement schemes that contain “sell-down” arrangements

wherein the ADB can transfer certain risks it has undertaken through transfers, assignments or novations.

European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD)

The EU goal of spending EUR100 billion on infrastructure by mobilizing public and private investment is a serious

commitment that requires new methods to tap resources. A slow recovery and low growth figures further complicate

the achievement of this target. The EBRD has consistently been providing focused financing for infrastructure projects

across the EU.

The EBRD also has several initiatives focusing on infrastructure development alongside the credit support systems

they provide. They have consistently provided co-financing, guarantees and syndications over the years, but have a

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 12

renewed interest in credit enhancement recently. In January 2015 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, the EBRD

floated the novel idea of setting up a fund capitalized by donor countries and MDBs that would be a partial guarantor

for infrastructure projects to provide a rating upgrade to attract institutional investors. This fund would be, when

implemented, a go-to setup for projects that would not be viable without assistance.

Syndications and Guarantees

The EBRD routinely lends support to various infrastructure projects in the region for risk sharing through “B” loans or

guarantees. The EBRD has employed credit-enhancement schemes quite heavily in its operations in the municipal

environment infrastructure (MEI) sector. In MEI, the EBRD has provided support through a broad range of financing

instruments that include credit-enhancing instruments such as junior debt, guarantees and targeted credit lines

(EBRD, 2013).

12

The goal, especially with the MEI sector, is to help transition the government to private sector

investments.

European Investment Bank (EIB)

The EIB has a long history of providing supportive mechanisms to projects. Some of the products include structured

finance instruments (for example, senior loans and guarantees incorporating pre-completion and early operational

risk), guarantees, and more recently, project bonds. In addition to these “blending” instruments, the EIB also focuses

on extensive green infrastructure investment (through schemes such as the Private Finance for Energy Eciency

[P4EE] and Natural Capital Financing Facility [NCFF]) (EIB Products, http://www.eib.org/products/index.htm).

13

Project Bond Credit-Enhancement scheme

The EIB launched the Project Bonds Initiative in 2012 to address the European Union’s 2020 objective of investment

of EUR2 trillion in infrastructure projects. The EIB will provide partial credit enhancement through a subordinated

instrument, either a loan or contingent facility, to improve the credit quality of senior project bonds issued by the

project company (“Senior Bonds”), and therefore increase their credit rating. This will be done by:

• a loan given to the project company from the outset (funded PBCE); or

• by way of a contingent credit line which can be drawn if the cash flows generated by the project are not

sucient to ensure Senior Bond debt service or to cover construction costs overruns (unfunded PBCE).

Contingent Loans

The EIB has enabled the issuance of long-term bonds for PPP projects by providing a contingent loan (i.e., one that is

to be used if the project is unable to repay the bondholders).

Inter-American Development Bank (IADB)

The Latin American region requires investment of about 5 per cent of its GDP (an amount equivalent to US$250

billion in 2010) to close the infrastructure gap. While some countries in Latin America see such investment in

infrastructure as a means to boost GDP growth, others require infrastructure development for provision of basic

needs (such as safe drinking water, electricity). The IADB provides several dierent types of financing to address

these financing requirements.

12

For instance, the EBRD enters into Project Support Agreements for projects in the water sector which provides a quasi-guarantee of tariff

shortfall. The experience of the EBRD in Romania is a good example of how PSAs helped transition the economy to a sustainable water

production system that is now mainly funded by private sector investors (World Economic Forum, 2014).

13

The NCFF is EUR125 million funding directed at projects that are focused on biodiversity and ecosystem services. Eligible projects can

receive direct funding or intermediated debt financing. The P4EE targets projects that are energy efficient and provides them with different

types of assistance such as credit risk protection, long-term financing and expert support services.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 13

Guarantees

The IADB provides PCGs and PRGs for the enhancement of bond issues, project finance or structured trade

finance transactions and securities backed by assets or future flows. They also oer local currency guarantees to

enable greater local lending and sovereign counter-guaranteed guarantees (the latter is a risk guarantee related to

government contractual obligations in a project). Apart from these more traditional forms of guarantees, the IADB

has recently begun to focus on ameliorating specific concerns such as construction risk in approved projects to

attract private financing. The IADB also caters to risk mitigation for green projects through performance guarantees

that address concerns for green infrastructure that may be unmet by credit guarantees.

International Finance Corporation (IFC)

The credit-enhancement schemes oered by the IFC may have slightly dierent characteristics, since the IFC lends

only to the private sector rather than the sovereign borrowers for the MDBs. This also means that there are some

interesting products that the IFC has brought forth. The IFC has used PCGs quite eectively for several projects, but

has also utilized new methods of providing lender confidence. The IFC has acted as anchor investor (the first investor

in a public oering who instills confidence in the project) and pulled together the IFC Global Infrastructure Fund that

seeks to fill the gap in the lack of funding in the sector. The IFC also provides interesting instruments such as a partial

swap guarantee to enable certain cross-border transactions.

World Bank Group (World Bank, MIGA, IBRD)

The World Bank provides several dierent types of guarantees such as PCGs (for public investment projects) to

sovereign governments and PRGs for private projects (BOTs, PPPs, etc.) to cover debt investments. The World Bank

also provides policy-based guarantees, which are essentially PCGs provided in support of commercial borrowings of

governments for budget financing or in support of reform programs. In addition to these, MIGA provides political risk

insurance to private sector companies or government-owned companies operating on a commercial basis.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 14

CHAPTER 3.

CASE STUDIES ON CREDIT

ENHANCEMENT

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 15

Chapter 3. Case Studies on Credit Enhancement

While the availability of credit-enhancement schemes has been outlined above, their uptake has been quite limited.

A number of reasons may be attributed to this, the most significant of which are:

(a) A lack of knowledge among governments about the credit-enhancement schemes available when

structuring transactions.

(b) Undeveloped procurement decision-making, including precise feasibility studies, to put together large

infrastructure deals, and identifying the risks to match them with the potential mitigation methods oered

by MDBs.

(c) When it comes to green infrastructure, the lack of understanding and technical inability to address these

risks.

In order to understand what makes a successful project with a credit-enhancement scheme by an MDB, it is helpful

to preview the stages that build up to it. Annex A to this paper provides a description of the common patterns of

projects’ internal processes of MDBs: the risk-assessment methods for large infrastructure projects at MDBs. This

chapter looks at the requirements to compile a project into an approvable structure, through a case study of large,

successful infrastructure projects, including green projects, that have received credit enhancement.

Successful Credit-Enhancement Projects

An analysis of some successful credit-enhancement infrastructure projects sheds light on the variety and nature of

proposals that are approved and implemented by MDBs.

All information and data presented below have been obtained from the project documentation listed for each project

described.

ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK: India – IIFCL (2012)

Background

The first of these projects is the partial credit guarantee facility in India. It was identified that the infrastructure market

in India was predominantly financed by the banking sector (infrastructure accounted for about 14 per cent of the asset

book of the Indian banking sector in 2011). With the increasing need for long-term lending to the sector, it was seen

as necessary to tap into funding apart from the traditional banking sector. The old-fashioned asset debt financing

methodology in India required a makeover in order to tap other credit sources such as pension and insurance funds—

this aligned with ADB’s strategy of developing local debt markets to fund infrastructure by 2020.

The Product

Under this first-of-a-kind US$128 million facility, developed with India Infrastructure Finance Company Limited

(IIFCL), ADB and domestic finance companies will provide partial guarantees on rupee-denominated bonds issued

by Indian companies to finance infrastructure projects. ADB will then take on a part of that guarantee risk, which

will improve the credit rating of an infrastructure project to A or AA (ADB, 2012). This opens up the market to

institutional investors such as pension funds that can only invest in assets graded AA or above, to buy the project

bonds. This is the first such program implemented for bonds issued by private companies. The first project under the

program to receive such an incentive is the GMR expressway linking two major cities in South India.

The project documentation (detailed in Text Box D below) is extremely helpful in identifying the main stages in the

project.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 16

The Significance

The eects of this groundbreaking scheme are evidence of its success:

(1) Development of the nascent bond market in India with a focus on infrastructure will lead to self-suciency

in the future.

(2) The partial credit guarantee intended to be provided for three to five projects over three years is more

eective than direct lending for a single project.

(3) Since the project is already in its operational phase, the risk it presents is that of tari collection and trac

volatility for debt service repayment, which is guaranteed by IIFCL and ADB.

(4) The participation of local approved financial institutions (which have government backing) ensures capacity

building in the country. A particular distinction of this project has been the guarantees oered by local banks

alongside IIFCL and ADB, since such programs are usually run only by high-level agencies or MDBs.

(5) An additional feature relates to the indirect positive externalities oered by these projects in that it helps to

developed local capital markets by being a source of more bond activity and it helps banks deleverage by

passing the debt burden to institutional investors.

(6) The ecacy of partial credit guarantees in the Indian market was recently commended by the Climate

Policy Initiative, which concluded that PCGs can mobilize additional capital from pension and insurance

funds and reduce cost of debt by up to 1.9 percentage points while also increasing tenor by up to five years

for the developers (Shrimali, Konda, & Srinivasan, 2014).

This project is an excellent example of an eective credit-enhancement scheme utilized to not only remove

impediments to financing, but also create a precedent for further mainstreaming infrastructure investment in the

markets. While this project is for financing a normal infrastructure project, the ADB does not particularly dierentiate

between brownfield and green infrastructure projects. So long as the quality of the o-take agreement and the credit

rating of the project is acceptable, the nature of the project will not aect its ability to garner credit-enhancement

schemes. The first utilization of the PCG was for the Jadcherla Expressway by GMR Constructions, which will be rated

AA by ICRA Ltd., an Indian credit ratings agency. The PCG scheme is to be extended to other identified infrastructure

projects in India.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 17

WORLD BANK GROUP: Nigeria – Power Sector Guarantees Project (2014)

Background

While Nigeria’s economic growth increased, there were fundamental issues with local infrastructure. Despite

extensive oil resources, access to electricity was limited and an obstacle to conducting business in Nigeria. With

limited fiscal resources, it was necessary to shore up private sector promotion along with public investment.

The Product

The Power Sector Guarantees Project (PSGP), launched in Nigeria by the World Bank, IFC and MIGA, seeks to

address the total power sector deficiencies in Nigeria. The PSGP is a package of loans and guarantees supporting a

series of energy projects.

14

The IBRD guarantees include forward-looking mitigation and risk-sharing arrangements,

designed to augment the power sector reforms while building market confidence and setting industry benchmarks.

The package also includes World Bank Partial Risk Guarantees and MIGA political risk insurance (details of these

instruments can be found in Box E below).

The Significance

The PSGP is innovative because it has been implemented on an extremely large scale and combines several

dierent instruments, including guarantees. The package includes two greenfield power projects that receive credit

enhancement and commercial debt mobilization guarantees that seek to mainstream the green energy projects into

Nigeria’s growing economy. The second main instrument is a partial risk guarantee that covers only those clearly

identifiable risks relating to subsidies and taris. The appraisal of the project led to the following conclusions regarding

viability and impact that could have been the deciding factors:

14

World Bank partial risk guarantees approved include up to US$245 million for the 459-megawatt (MW) Azura Edo power plant near Benin

City, Edo State; and up to US$150 million for the 533-MW Qua Iboe plant in Ibeno, Akwa Ibom State. Both plants are gas-fired. The Boards

of IFC and MIGA approved loans and hedging instruments of up to US$135 million and guarantees of up to US$659 million for the Azura

Edo project.

TEXT BOX D. PROJECT DOCUMENTATION FOR THE IIFCL PROJECT

The project documentation for the IIFCL project is helpful to understand the rationale for the success of the project.

Capacity Development Report – PCG Features:

The first report provided upon project identification is prepared by CRISIL, the Indian arm of the international rating

agency Standard & Poor, and outlines the characteristics of PCGs in general and past experiences of the ADB with

PCGs in India. This is a vital document in that it convinces lenders of the value of the ADB’s involvement in the project.

Progress report – PCG Structure and Mechanics:

The second report, also prepared by CRISIL, advises the technical assistants to the project at the ADB of the structure

and working mechanics of the PCG. This is extensive, covering the optimal PCG structure for IIFCL, a financial study of

the bond portfolio, project outflows, and a breakdown of various case scenarios of issuing the PCG, including lessons

learnt.

ESIA:

IIFCL then prepared an environmental and social audit report of the first project for which the PCG will be employed.

Report and Recommendation:

Finally, before the project is approved, the Report and Recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors is

submitted. This outlines the research and strategy of the team, including detailed financial analysis that is presented

to the Board to explain the risks that the ADB takes on, the mitigation systems in place and the importance of ADB’s

involvement in the project.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 18

(1) The influence of the PGSP in developing the energy sector would have ramifications in the comprehensive

development of Nigeria.

(2) Given the scale of financing required, rather than provide direct lending, the credit-enhancement guarantees

promote private sector investment.

(3) The PRG provided by the IBRD to commercial lenders serves two vital purposes – it invites increased private

investment and it reduces the exposure of the IBRD (as the government entity providing an indemnity to

IBRD is buered by the sale of government power projects).

(4) The World Bank Group’s presence creates comfort for foreign institutional investors as well.

Credit-enhancement schemes given out by the World Bank Group are quite popular among African countries,

especially for energy projects. The unavailability of commercial instruments encourages project developers to seek

government or MDB assistance in reducing contractual risks. The World Bank Group, in collaboration with PPIAF,

also provided assistance in project preparation stage–upstream phase for creation of feasibility studies, identifying

risks and correct structuring for the same.

INTER-AMERICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK: Mexico - Geothermal Project

(2014)

Background

The need to reduce carbon emissions through increased use of green energy sources was the basis of this project

and its financing. Geothermal potential in Mexico is extremely high, and the development of this project would be in

line with the objectives of the government in advancing the sector. The major issues that geothermal energy projects

face, such as unpredictable exploratory costs, high upfront costs for the project and long maturity periods, could be

ameliorated with the correct type of financing.

TEXT BOX E

Project Information Document (Concept stage):

This document is prepared at the concept stage and reviews the status of the power sector and the issues it faces

(including distribution, taris, systematic power purchase agreements). The paper outlines the proposed objectives

and methodology.

Project Appraisal document:

This is an extremely detailed document with information about the specific risks and their mitigation, the exact structure

of the project and the role of each MDB in the same. The appraisal includes project mechanics, implementation

methodology, financial and technical analysis and a look at the environmental and social safeguards.

Project Information Document (Appraisal stage):

The World Bank then prepares a summary of the project, its context and description and proposed structure.

Chair summary:

This is the document ultimately released by the Board at the World Bank confirming the approval of this project. The

Board notes the high-risk, high-reward nature of the project and the importance of the involvement of the World Bank

entities at the early stages to garner private investment.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 19

TEXT BOX F

Indicative Information Technical Eligibility:

This document is an initial standard form that reviews and answers queries on the project that indicate whether it is

eligible for funding by the IADB.

Monitoring and Evaluation Plan, Financing schemes:

These documents provide general details about the proposed project, its working schematics and plans for monitoring

once implementation is complete.

Loan Proposal:

This is a detailed document that describes the project, how it fits into the IADB’s goals, the risks associated with the

project, their mitigation mechanisms and the implementation and management plan for the project.

Board Resolution:

Upon receipt of the loan proposal, the Board confirms acceptance of the project and it is then administered.

The Project

The unique challenges presented by the nature of the project and the specific risks associated with it required

particularized solutions. The project deployed IADB resources to provide direct financial support to developers

through various methods—direct loans, contingent loans, first-loss guarantees and insured loans (details of some

project documentation can be found in Box F below). The intention is to create bankable geothermal projects to

attract private funding and mobilizing capital to boost growth in the industry in the long term.

The Significance

This project is a notable example of innovative financing to address precise problems posed by green projects. The

following are the takeaways from this project:

(1) The risk-mitigation mechanism is based on the identification of a single specific issue (exploration costs)

that requires attention in order to promote and develop local green energy.

(2) The IADB uses a “loan-guarantee,” which is paid back only if the exploratory phase proves to be successful

in finding enough energy sources. This ensures that the costs associated up front are not a deterrent for

future investors.

(3) This scheme not only promotes green energy growth, it also attracts private investment to fund such green

projects.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 20

CHAPTER 4.

RISK MITIGATION IN

GREEN INFRASTRUCTURE

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 21

Chapter 4. Risk Mitigation in Green Infrastructure

Credit-enhancement schemes are intended to target precise risks that infrastructure (or other projects) pose.

As discussed in chapters 2 and 3 above, the nature of the project determines the risks, their perception and their

mitigation. The identification of risks in a project occurs at the project appraisal stage, which then helps determine

the type of mechanism that can be used in the implementation stage to ameliorate these risks. Though the exposure

for an MDB diers for a direct loan (where it bears all risks as a lender) and a credit-enhancement mechanism (where

it has limited coverage and receives an indemnity from the parastatal entity), the internal processes for both are the

same. In fact, MDBs do not distinguish between the dierent types of projects (brownfield or green energy) or the

dierent types of financing for processing assistance.

The real and perceived risks associated with green infrastructure projects are less attractive to commercial lenders.

Green infrastructure projects also present technical issues that are often not understood by less sophisticated

investors or in developing economies.

The importance of the three examples discussed above lies in the use of credit-enhancement mechanisms to address

risks that prevent the project from being bankable. In the India–IIFCL project, the trac and tari risk prevented

the roadways project from obtaining private uptake; while it was the combined regulatory, new-market and tari

pricing risk in the PSGP and the exploratory and upfront costs in the geothermal project. The credit-enhancement

mechanisms used in each of these projects addressed the specific risk to make the project more attractive to private

investors. The crucial element in each of these projects has been the identification of that troublesome risk, a potential

solution oered by an MDB and the correlation and application of the two together. This is an important lesson for

project proposal preparation for any infrastructure project, but in the case of green infrastructure it is an essential

aspect.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 22

CHAPTER 5.

CONCLUSIONS

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 23

Chapter 5. Conclusions

There are several significant challenges for mainstreaming green infrastructure financing, in the road ahead through

credit-enhancement schemes. But a review of the mechanisms available and an understanding of their successful

operation—not only in infrastructure projects generally, but for green infrastructure in particular—provides an idea of

how this road can be traversed.

The more general issues of lack of knowledge can be addressed and are being considered by several agencies,

including MDBs. There are active eorts in marketing the new instruments to the potential investor pool along with

workshops on the advantages of such instruments. On the preparation side, most MDBs provide extensive support in

making feasibility reports through technical assistance teams that also participate in the project identification stages.

When it comes to green infrastructure specifically, it is imperative that knowledge dissemination take place at two

levels. First, governments require technical assistance to understand the benefits of and promote green infrastructure

project proposals. Second, investing banks need training to consider green projects and not be averse to the risks they

present. The latter of these concerns is being addressed by some MDBs such as the IADB and the EBRD who give

technical know-how to the local commercial banks they work with.

There is a need for greater uptake of credit-enhancement schemes, which can only increase if there is knowledge

dissemination and endorsement of these schemes with both governments (who originate projects), MDBs (who

provide the necessary mechanisms) and private investors (who are the final objectives of this process). An intensified

relationship among these key players is crucial to strengthening the acceptance and implementation of credit-

enhancement schemes. Governments need to take the first step in not only identifying suitable projects, but also the

inherent risks involved. This enables the second player, the MDB, to work with the governments to devise a potential

mitigation strategy for those specific risks. Only once these two stages are successful can enlightened investors step

in to provide financing to larger number of projects.

There are several suggested means of improving the ecacy of existing credit-enhancement schemes. One such

method is to create a combined pool of credit-enhanced investments that are aggregated according to the risks

they represent. This would be eective for marketing to private sector investors, who will then have the option of

buying into these risks in a fashion similar to that of insurance products. While this system would require extensive

organization and coordination, it does have potential to make the uptake of credit enhancement schemes more

widespread. Another promising endeavour is that mooted by the EBRD to pool resources for a dedicated funding

system that focuses on providing risk-mitigating guarantees for infrastructure projects. The box below also lists some

important questions that need attention in order to resolve the issues identified in this paper.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 24

The case studies above highlight the importance of the following:

(1) Identify and iterate issues in projects. While there are challenges going in to any project (in terms of risks,

perception of these risks, lack of knowledge, lack of coordination) it is necessary to recognize, iterate and

classify these issues. This enables the second stage of planning amelioration.

(2) Innovation is key. The input from various participants is crucial to creating a complex (such as the PSGP) or

simple (such as the geothermal project) solution to mitigate risks.

(3) Continuity of local development is an essential goal in all cases. The IIFCL project is an excellent example of

promoting local future growth without constant MDB or other outside assistance.

While these are onerous tasks, they are the first step towards bridging the infrastructure gap. Especially when

it comes to green infrastructure development, it is important to start early to ensure that all potential investors

(whether they be large insurance funds looking to invest in climate friendly projects to reduce future potential claims

or pension funds that have capacity to invest in credit-graded projects) are aware and equipped to mainstream green

infrastructure financing.

TEXT BOX G

While there are several initiatives by MDBs to promote credit enhancement, there have been some real obstacles in

their practical application.*

(1) In some countries (such as India), there has been reluctance from the local banks that finance infrastructure

projects to accept credit enhancement of the project once it has started producing results. The credit-enhanced project

will usually take on new investors, with the initially investing banks being repaid. Banks see this as a wasted opportunity,

having sunk in the initial costs yet not able to realize the returns once the project is operational. It is to be questioned

whether the banks are actually correct in their approach. The repayment of the initial debt frees up capital for investment

in other ventures and encourages new and dierent forms of investment into infrastructure.

(2) MDBs have a single processing mechanism for all types of loan requests, whether it is a request for a full direct loan

or credit enhancement. It may be helpful to review these processes to evolve simpler procedures for credit-enhancement

mechanisms since they present lesser risks to the MDB or a parallel route with more guidance on structuring for credit

enhancement of a project.

(3) Similar to the singular processing mechanisms for dierent types of loans, MDBs do not dierentiate the risk

assessment for green projects and other projects. Keeping in mind the dierences in the real and perceived risks for

green infrastructure projects (especially the reluctance amongst even MDBs to buy down technical risks), it could be

helpful to have focused project approval mechanisms that cater to green projects. While a number of MDBs and IFIs

have green investment targets, the processes for approval of funding for green infrastructure remains the same as other

infrastructure, which may need to be reconsidered.

* This information was gathered from the interviews with MDB personnel and through relevant research about the projects

analyzed for the case studies in this paper.

Credit Enhancement for Green Projects 25

References

African Development Bank (AfDB). (2013). Needs assessment for risk mitigation in Africa: Demands and solutions.

Retrieved from http://www.icafrica.org/fileadmin/documents/Knowledge/ICA_publications/IRMA%20

FINAL%20REPORT-AfDB%20Ocial%20v2.pdf

Asian Development Bank (ADB). (2006). Review of ADB’s credit enhancement operations. Retrieved from http://www.

adb.org/documents/review-adbs-credit-enhancement-operations

ADB (2011). Strengthening capacity of developing member countries for managing credit enhancement products.

Retrieved from http://www10.iadb.org/intal/intalcdi/PE/2012/10481.pdf

ADB. (2012). Groundbreaking ADB facility to mobilize finance for critical India infrastructure (Press Release). Retrieved

from http://www.adb.org/news/groundbreaking-adb-facility-mobilize-finance-critical-india-infrastructure