FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 35

The Role of Bank Credit

Enhancements

in Securitization

1.Introduction

oes the advance of securitization—a key element in the

evolution from banking to “shadow banking” (Pozsar et al.

2010)

1

—signal the decline of traditional banking? Not

necessarily, for banks play a vital role in the securitization

process at a number of stages, including the provision of credit

enhancements.

2

Credit enhancements are protection, in the

form of financial support, to cover losses on securitized assets

in adverse conditions (Standard and Poor’s 2008). They are

in effect the “magic elixir” that enables bankers to convert

pools of even poorly rated loans or mortgages into highly rated

securities. Some enhancements, such as standby letters of

credit, are very much in the spirit of traditional banking and

are thus far from the world of shadow banking.

This article looks at enhancements provided by banks in the

securitization market. We start with a set of new facts on the

evolution of enhancement volume provided by U.S. bank

holding companies (BHCs). We highlight the importance of

bank-provided enhancements in the securitization market by

comparing their market share with that of financial guaranties

sold by insurance companies, one of the main sellers of credit

protection in the securitization market. Contrary to the notion

1

According to Federal Reserve Chairman Bernanke (2012), “Examples of

important components of the shadow banking system include securitization

vehicles.”

2

See Cetorelli and Peristiani (2012) for analysis of banks’ role in other steps

in the securitization process.

that banks were being eclipsed by other institutions in the

shadow banking system, we find that banks have held their

own against insurance firms in the enhancement business.

In fact, insurers are forthright about the competition they

face from banks:

Our financial guaranty insurance and reinsurance

businesses also compete with other forms of credit

enhancement, including letters of credit, guaranties and

credit default swaps provided, in most cases, by banks,

derivative products companies, and other financial

institutions or governmental agencies, some of which have

greater financial resources than we do, may not be facing

the same market perceptions regarding their stability that

we are facing and/or have been assigned the highest credit

ratings awarded by one or more of the major rating agencies

(Radian Groups 2007, form 10-K, p. 46).

Given the steady presence of bank-provided enhance-

ments in the securitization market, we next study exactly

what role enhancements play in banks’ securitization process.

The level of credit enhancements necessary to achieve a given

rating is determined by a fairly mechanical procedure that

reflects the rater’s estimated loss function on the underlying

collateral in the securitization (Ashcraft and Schuermann

2008). If estimated losses are high, then—all else equal—

more enhancements are called for to achieve a given rating.

Those mechanics suggest a negative relationship between

Benjamin H. Mandel is a former assistant economist and Donald Morgan an

assistant vice president at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Chenyang

Wei is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Correspondence: don.morgan@ny.frb.org

The authors thank Nicola Cetorelli, Ken Garbade, Stavros Peristiani, and

James Vickery for helpful comments and Peter Hull for outstanding research

assistance. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily

reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal

Reserve System.

Benjamin H. Mandel, Donald Morgan, and Chenyang Wei

D

36 The Role of Bank Credit Enhancements in Securitization

the level of enhancements on a deal and the performance of

securitized assets. Note that in this scenario, enhancements

serve as a buffer against observable risk (as embodied in the

estimated loss function).

We are interested in the idea that enhancements might also

be used to solve part of the asymmetric information problems

that may plague the securitization process. If banks are better

informed than outside investors about the quality of the assets

they are securitizing, as they almost certainly are, banks that are

securitizing higher-quality assets may use enhancements as a

signal of their quality. In other words, by their willingness to

keep “skin in the game” to retain some risk, banks can signal

their faith in the quality of their assets. Such signaling implies

a positive relationship between the level of enhancements and

the performance of securitized assets, just the opposite of the

buffer explanation. Obviously, enhancements could, and

probably do, serve both as a buffer against observable risk

and a signal against unobservable (to outsiders) quality.

However, since the buffer role is almost self-evidently true,

we are interested in whether we can detect any evidence for

the role of securitization enhancements as a signal.

Others have also considered the hypothesis that

enhancements might play a signaling role. Downing, Jaffee,

and Wallace (2009) observe that asymmetric information

about prepayment risk in the government-sponsored-

enterprise (GSE) mortgage-backed-security market should

motivate the use of signaling devices.

3

Albertazzi et al. (2011)

note the potential centrality of asymmetric information to

the securitization process and conjecture that a securitizing

sponsor can keep a junior (equity) tranche “as a signaling”

device of its (unobservable) quality or as an expression of a

commitment to continue monitoring. James (2010) comments

that if asset-backed securities include a moral hazard (or

“lemons”) discount due to asymmetric information, issuers

have an incentive to retain some risk “as a way of

demonstrating higher underwriting standards.”

4

A variant of the question we are asking about credit

enhancements showed up in earlier literature on the role

of collateral in traditional (on-the-books) bank lending.

A theoretical literature in the 1980s predicted that in the

context of asymmetric information, safer borrowers were more

likely to pledge collateral to distinguish themselves from riskier

ones (Besanko and Thakor 1987; Chan and Kanatas 1985).

However, an empirical study by Berger and Udell (1990) found

strong evidence against the signaling hypothesis: that is,

3

Because the mortgage-backed securities that the authors study are

guaranteed, prepayment risk is the only risk investors need to worry about.

4

In a paper that is somewhat related to ours, Erel, Nadauld, and Stulz (2011,

p. 37) investigate why banks hold highly rated tranches of securitizations,

and conclude that their doing so may partly serve as “a credible signal of deal

quality to potential investors.”

collateral was associated with riskier borrowers and loans.

In other words, when it comes to loans on the books, collateral

seems to serve more as a buffer against observable risk than

as a signal of unobservable quality.

We found only one other paper that looks at the relationship

between enhancements and the performance of securitized

assets. Using loan-level data, Ashcraft, Vickery, and

Goldsmith-Pinkham (2010) find that delinquency on

underlying subprime and Alt-A mortgage pools is positively

associated with the amount of AAA subordination.

5

Those

results are consistent with the hypothesis that subordination is

used as a buffer against observable credit risk. Interestingly,

however, the authors find that BBB subordination is negatively

associated with mortgage performance on Alt-A deals, which

they consider more opaque (hard to rate). The latter result

seems consistent with the signaling hypothesis: the issuer of an

opaque security submits to a high degree of subordination to

signal its confidence in the quality of the assets it is selling.

We investigate our question from two angles. First, we look

directly at the relationship between the performance of

securitized assets and total enhancements in a panel analysis

where we regress the fraction of securitized assets that are

severely delinquent (delinquent for ninety or more days or

charged off) on total enhancements per unit of securitized

assets. We estimate the regression for seven categories of credit:

residential real estate loans, home equity loans, credit card

loans, auto loans, other consumer loans, all other loans, and

total securitizations. We are not able to detect any evidence

for the signaling hypothesis; when we find a significant

relationship between delinquency on securitized assets and

enhancements, the relationship is positive, consistent with

the buffer hypothesis.

In the second part of our article, we test the hypotheses

from the perspective of market participants. Specifically,

we investigate how stock investors and the option market

reacted when BHCs detailed for the first time their

securitization activity in their 2001:Q2 regulatory reports,

which include enhancements and aggregate loan performance

(delinquencies) of the assets that BHCs securitized. We

calculate the cumulative abnormal stock return around that

date for each BHC that had positive securitization activity.

We find first that abnormal returns are highly positively

correlated with the extent of securitization activity at a

BHC. That comes as no surprise, since securitization was

presumably viewed at the time as positive net-present-value

(NPV) activity. More interestingly, we find that the

relationship between total credit enhancements and

5

The amount of subordination at a given rating is the fraction of bonds that

absorb losses before the bond in question. If 90 percent of the bonds in a deal

are senior AAA bonds and 10 percent are junior, subordination of the AAA

bonds is 10 percent.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 37

cumulative abnormal returns depends on the delinquency rate

on securitized assets; when the rate is below some threshold,

cumulative abnormal returns are positively correlated with

total credit enhancements. This result suggests that when the

delinquency rate is relatively low, enhancements serve as a

signal of quality (hence, the high cumulative abnormal

return). However, when the rate is above that threshold,

the relationship between enhancements and cumulative

abnormal returns becomes negative. This finding suggests

that when the delinquency rate is relatively high—meaning

that securitized assets are demonstrably risky—enhancements

serve as a buffer against observable risk.

We also examine how securitization activity and

enhancements are related to BHC risk, as measured by

the implied volatility of BHC stock prices. We find that

securitization activity is positively correlated with implied

volatility, suggesting that markets view securitization as a risky

activity. We also find that total enhancements are positively

related to implied volatility. This result implies that just as

traditional originate-and-hold banking exposed bank

shareholders to risk, so does banks’ provision of credit

enhancements.

2. Background on Bank-Provided

Credit Enhancements

While credit enhancements can take many forms, Schedule

HC-S, on which BHCs report on their securitization activity,

includes fields for three types of enhancements.

6

The first is

credit-enhancing, interest-only strips. Schedule HC-S

instructions define these strips as:

an on-balance-sheet asset that, in form or in substance,

1) represents the contractual right to receive some or

all of the interest due on the transferred assets; and

2) exposes the bank to credit risk that exceeds its pro-rata

share claim on the underlying assets whether through

subordination provisions or other credit-enhancing

techniques.

Elsewhere, the HC-S instructions note that the field for

credit-enhancing, interest-only strips can include excess spread

accounts.

7

Excess spread is the monthly revenue remaining on

6

To be clear, our article focuses on the three types of enhancements reported

by bank holding companies on Schedule HC-S. For a more general discussion

of enhancements, see Ashcraft and Schuermann (2008).

7

Levitin (2011, p. 16) asserts that, in the context of credit card securitization,

excess spread accounts are also referred to as credit-enhancing, interest-only

strips.

a securitization after all payments to investors, servicing fees,

and charge-offs. As such, excess spread—a measure of how

profitable the securitization is—provides assurance to

investors in the deal that they will be paid as promised. Excess

spread accounts are the first line of defense against losses to

investors, as the accounts must be exhausted before even the

most subordinated investors incur losses.

The second class of enhancements, subordinated securities

and other residual interest, is a standard-form credit

enhancement. By holding a subordinated or junior claim, the

bank that securitized the assets is in the position of being a first-

loss bearer, thereby providing protection to more senior

claimants. In that sense, subordination serves basically as a

buffer or collateral. However, in the asymmetric information

context, holding a subordinate claim gives the bank the stake

that can motivate it to screen the loans carefully before it

securitizes them and to continue monitoring the loans after it

securitizes them. The bank’s willingness to keep some risk may

serve as a signal that it has screened loans adequately and plans

to monitor diligently.

The third class of enhancements, standby letters of credit,

obligates the bank to provide funding to a securitization

structure to ensure that investors receive timely payment on

the issued securities (for example, by smoothing timing

differences in the receipt of interest and principal payments) or

to ensure that investors receive payment in the event of market

disruptions. The facility is counted as an enhancement if and

only if advances through the facility are subordinate to other

claims on the cash flow from the securitized assets.

8

Although not technically classified as an enhancement, a

fourth item on Schedule HC-S that we consider is unused

commitments to provide liquidity. Unused commitments

represent the undrawn balance on previous commitments.

We include this variable simply as a control; we do not venture

a hypothesis about how it will enter any of our regressions.

It is important to note that the HC-S data we study,

particularly subordination, are measures of risk retention by

BHCs and not necessarily a total credit enhancement for a

securitization deal. For example, a deal could have 20 percent

subordination (say, a $1 billion mortgage pool divided into an

$800 million senior bond and a $200 million junior bond)

without the BHC holding (retaining) any of the subordinated

piece. In that case, the enhancement would not show up in our

data. Our basic question, however, remains: Is risk retention

important because it is a buffer against observable risk or

because it is a signal of unobservable quality? Indeed, Title 9

of the Dodd-Frank Act requires federal regulators to set

8

Note that banks also provide enhancements in the form of representation

and warranties that obligate the issuer to take back the loan if it defaults early

in its life.

38 The Role of Bank Credit Enhancements in Securitization

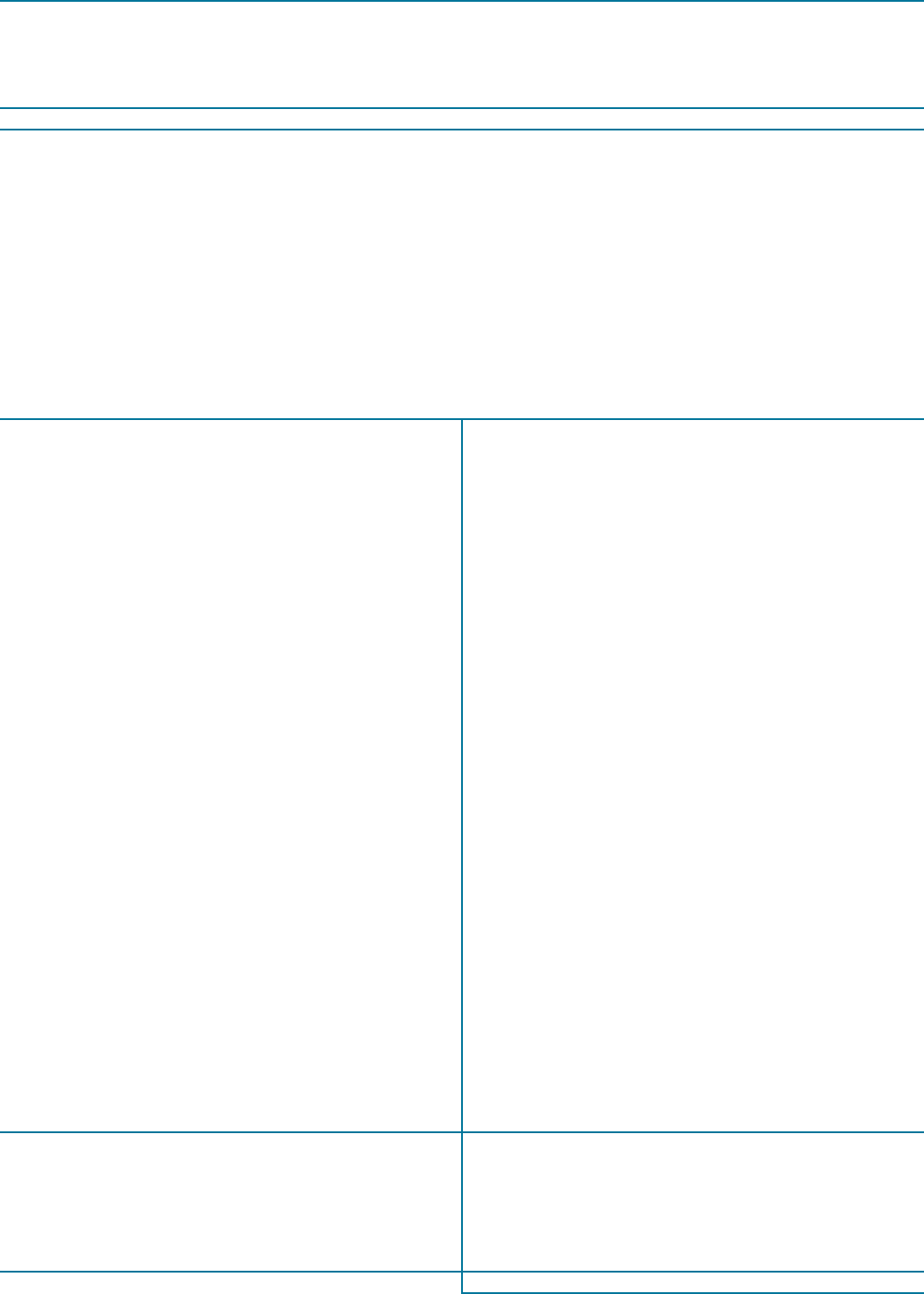

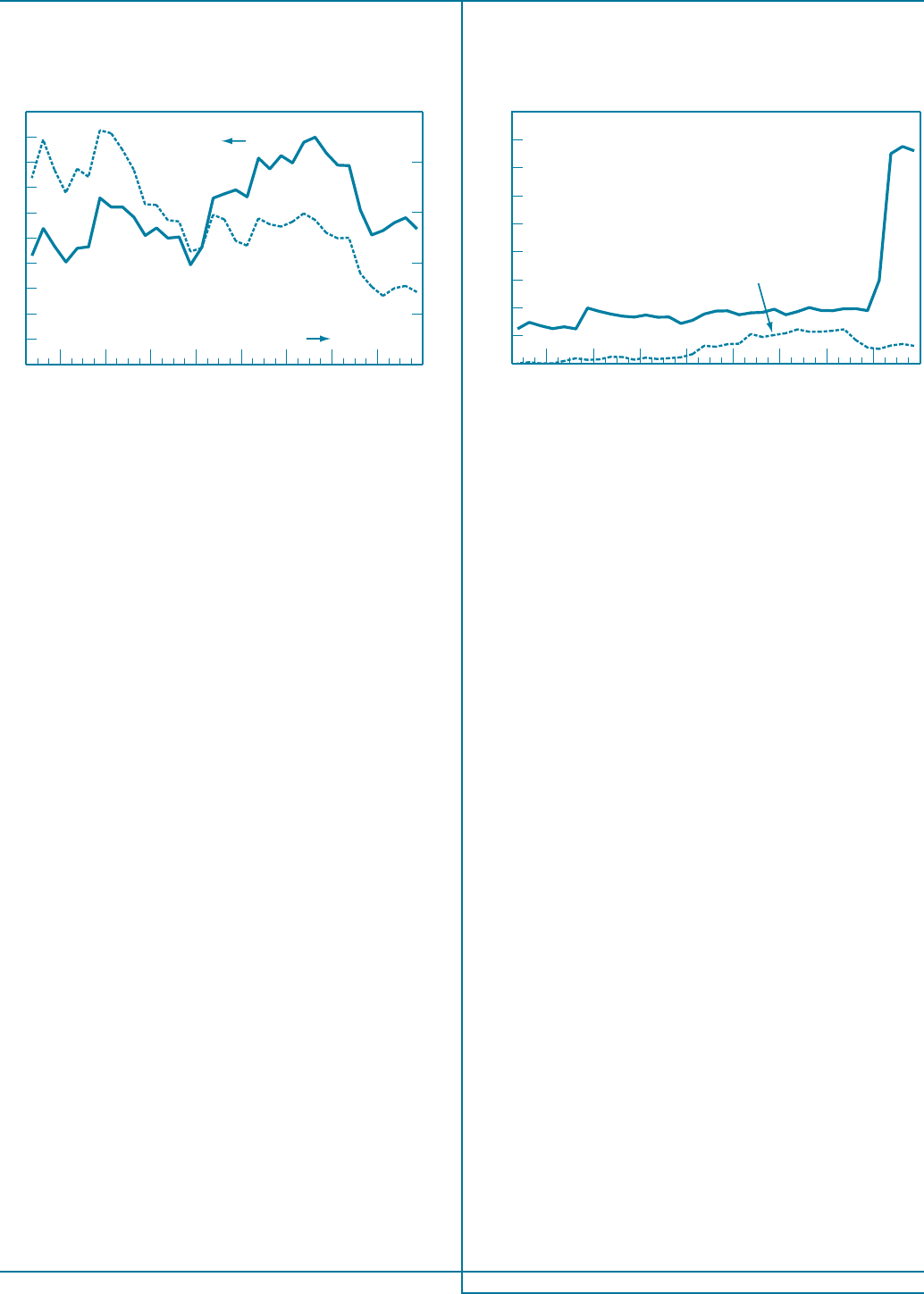

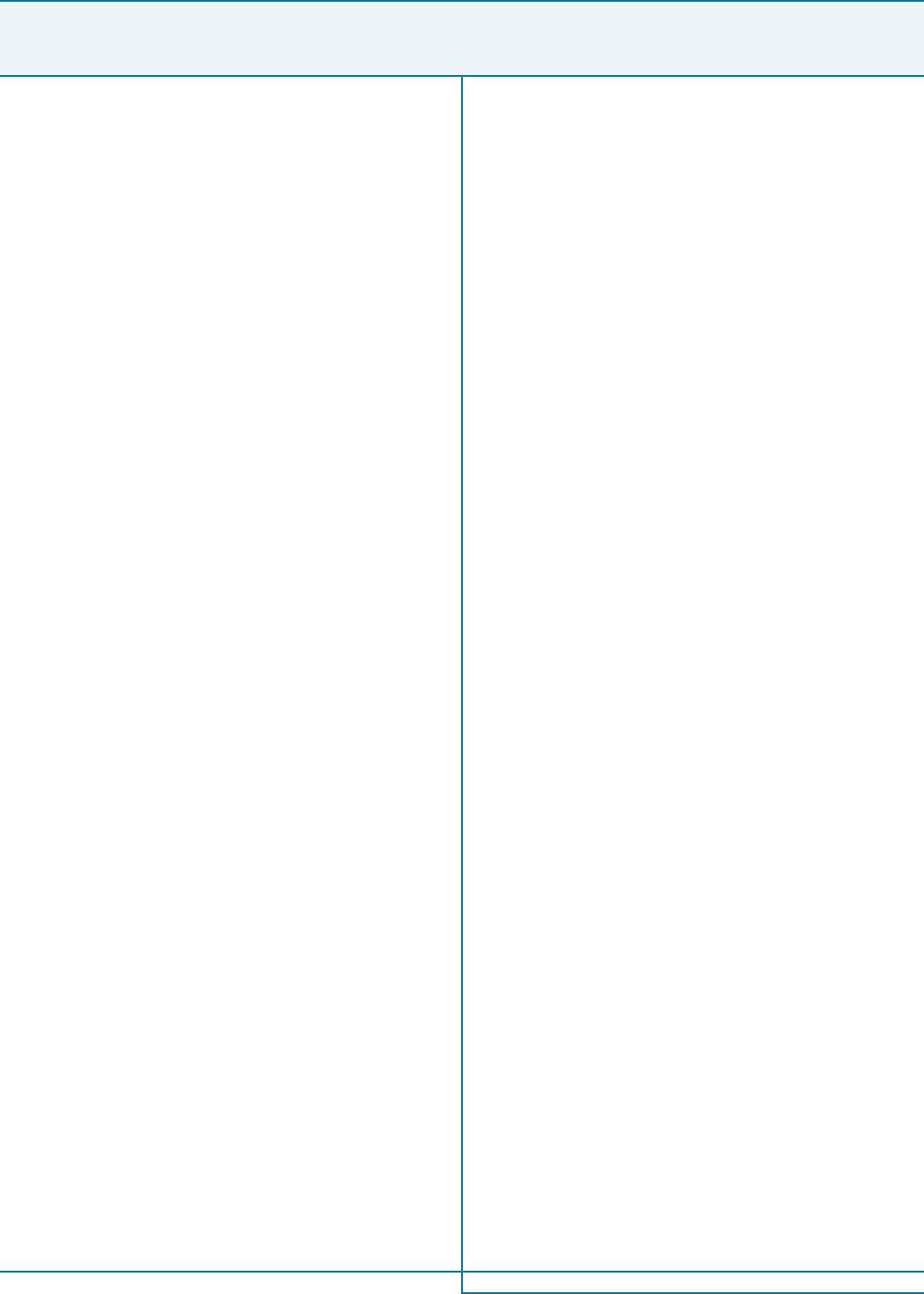

Source: Federal Reserve System, Form FR Y-9C, Schedule HC-S.

Chart 1

Total Credit Enhancements

by Bank Holding Companies

Billions of U.S. dollars Percent

Enhancements as share

of outstanding securitizations

Scale

Total enhancements

Scale

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

09080706050403022001

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

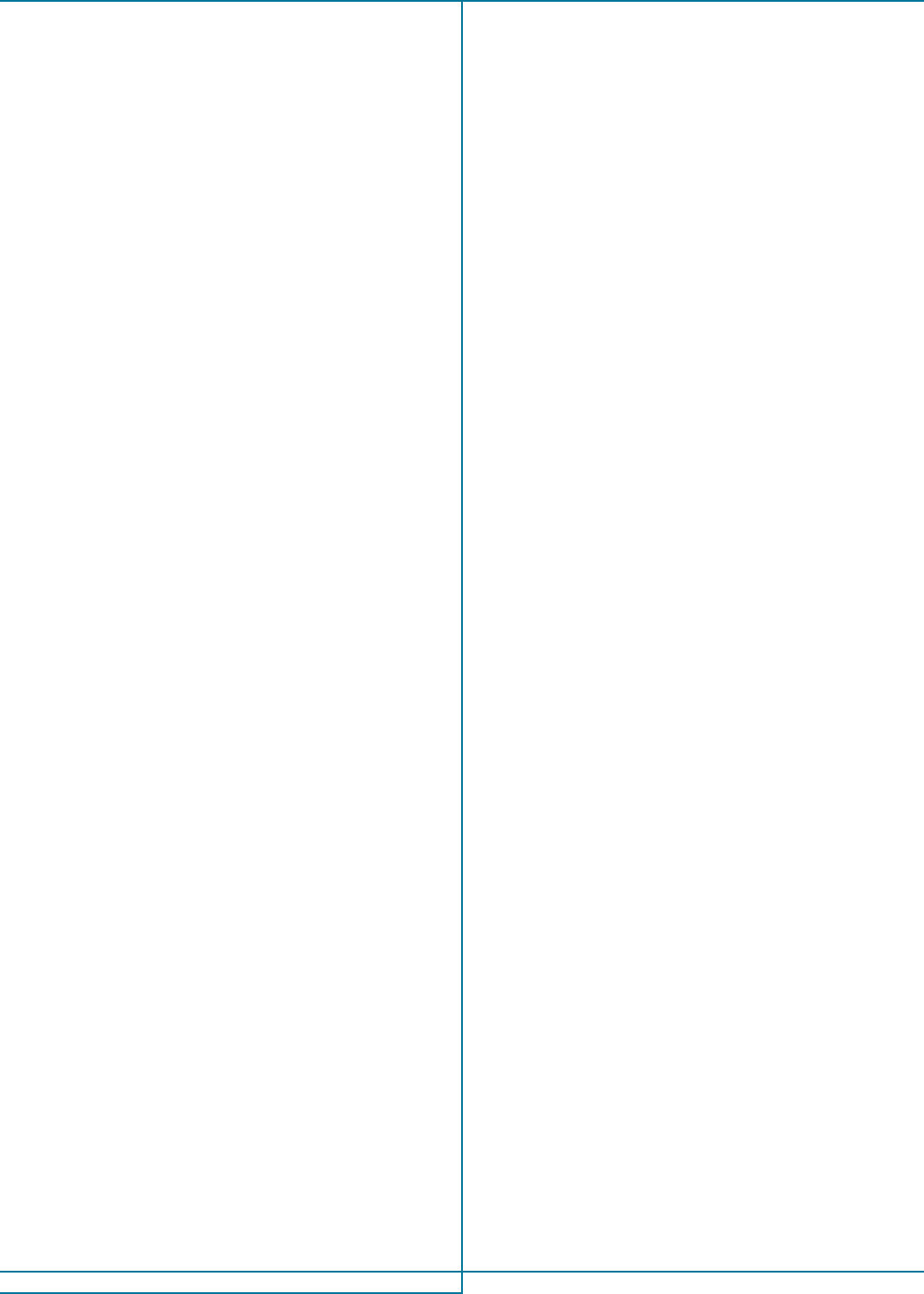

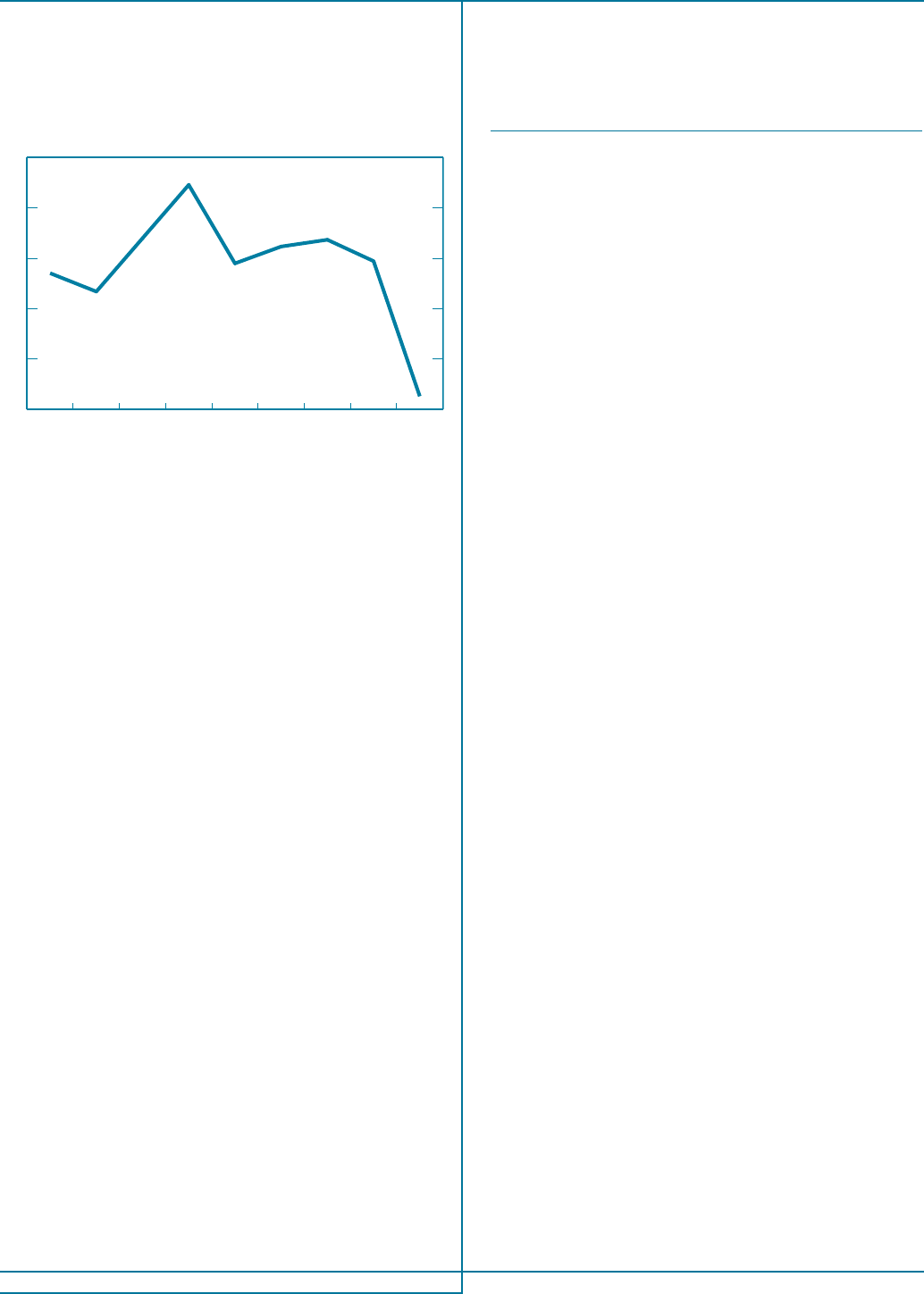

Source: Federal Reserve System, Form FR Y-9C, Schedule HC-S.

Chart 2

Credit Card Enhancements

by Bank Holding Companies

Billions of U.S. dollars Percent

Enhancements as

share of outstanding

credit card securitizations

Scale

Total enhancements

Scale

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

09080706050403022001

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

mandatory retention standards for sponsors of asset-backed

securities, suggesting that some policymakers believe that

enhancements in the form of retentions can ameliorate the

incentive and information problems endemic to securitization.

Because the enhancement data in Schedule HC-S have not,

to our knowledge, been studied publicly before, we briefly

examine the data in graphic form to get a sense of the size,

trends, and volatility of enhancements by BHCs. The data run

from 2001:Q2, when BHCs were first required to disclose

securitization activity, to 2009:Q4, when BHCs were required,

per Financial Accounting Standards Board ruling 167,

9

to bring

securitized assets back on their balance sheets (and thus ceased

to report most enhancements).

Chart 1 plots total enhancements in billions of dollars and

as a percentage of outstanding securitizations. Measured per

securitized asset, enhancements were more or less stable at

between 2 and 3 percent until 2009:Q1, although there is a

slight upward trend in the series to that point. In dollar terms,

total enhancements trended upward from about $25 billion

in 2001:Q2 to about $70 billion in 2009:Q1. In the following

quarter, total enhancements more than doubled, to

$164 billion, and enhancements per securitized asset rose

to about 6 percent.

Chart 2 shows that the abrupt increase in total enhance-

ments in 2009 came about almost entirely because of a rise in

enhancements on securitized credit card loans. The increase

in credit card enhancements, in turn, came about because of

increased enhancements at two BHCs: Bank of America and

9

See http://www.fasb.org/cs/ContentServer?c=FASBContent_C&pagename

=FASB/FASBContent_C/NewsPage&cid=1176156240834.

JPMorgan Chase (JPMC). The increase at Bank of America

followed purchases of new securitization trusts after it acquired

Merrill Lynch in 2009. More interestingly, perhaps, the

increase in enhancements at JPMC in 2009 occurred primarily

because several classes of notes issued by Chase Issuance Trust,

one of its master trusts of securitized credit card assets, were

placed on credit watch and one class of notes was down-

graded.

10

That case illustrates how enhancements are used

to maintain a given rating level, whether by providing

a buffer against collateral losses, a signal of faith in the quality

of the assets, or both.

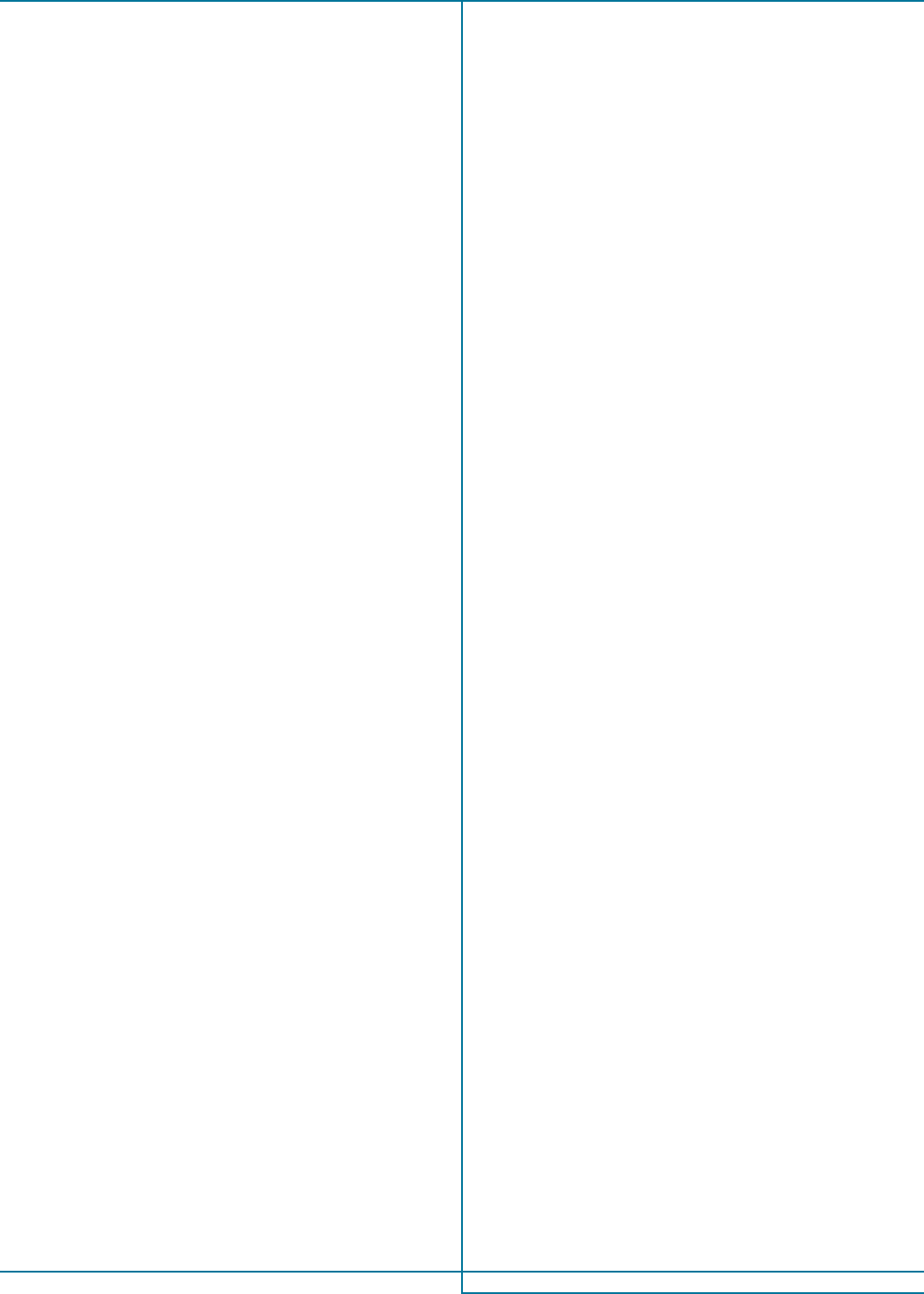

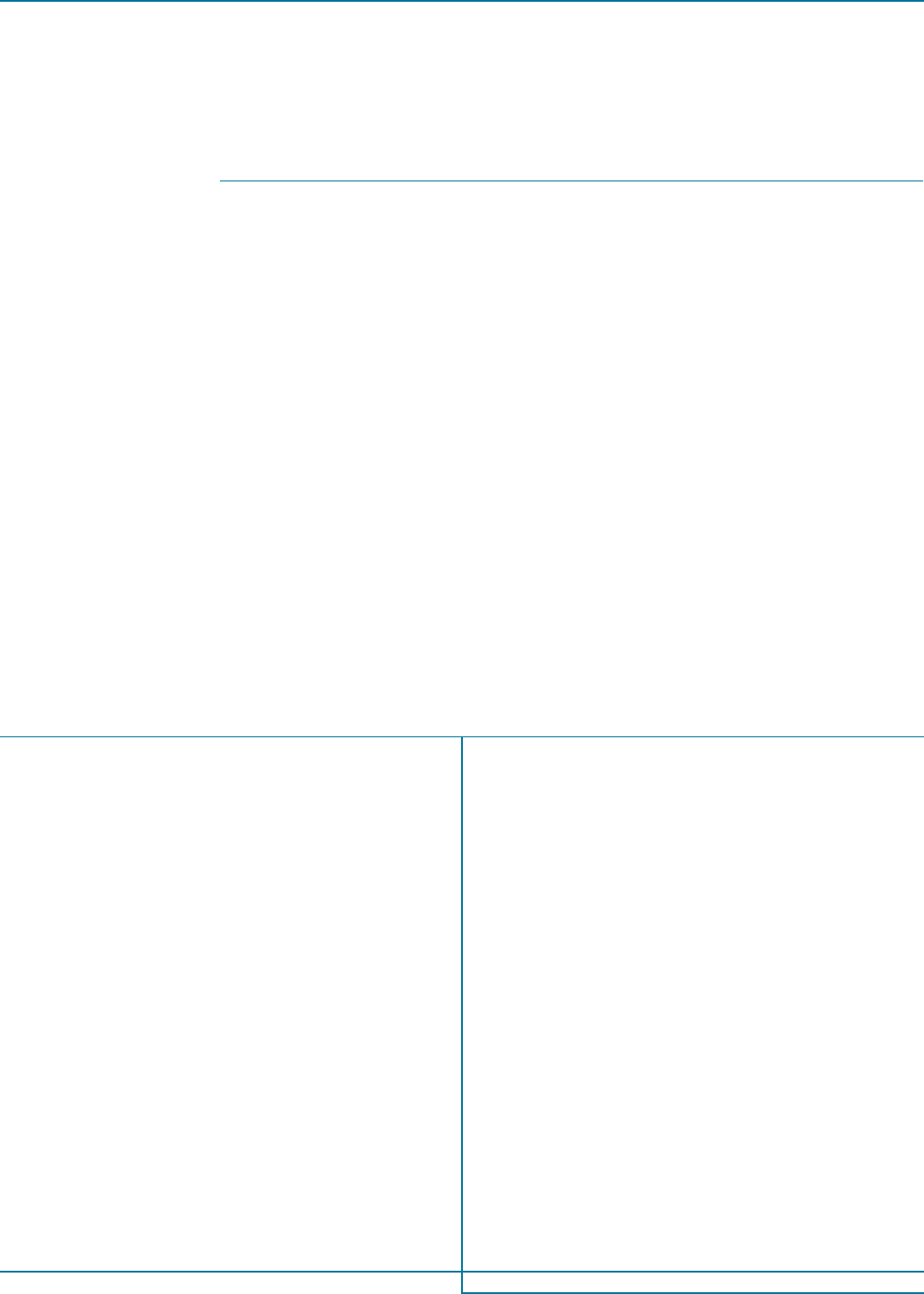

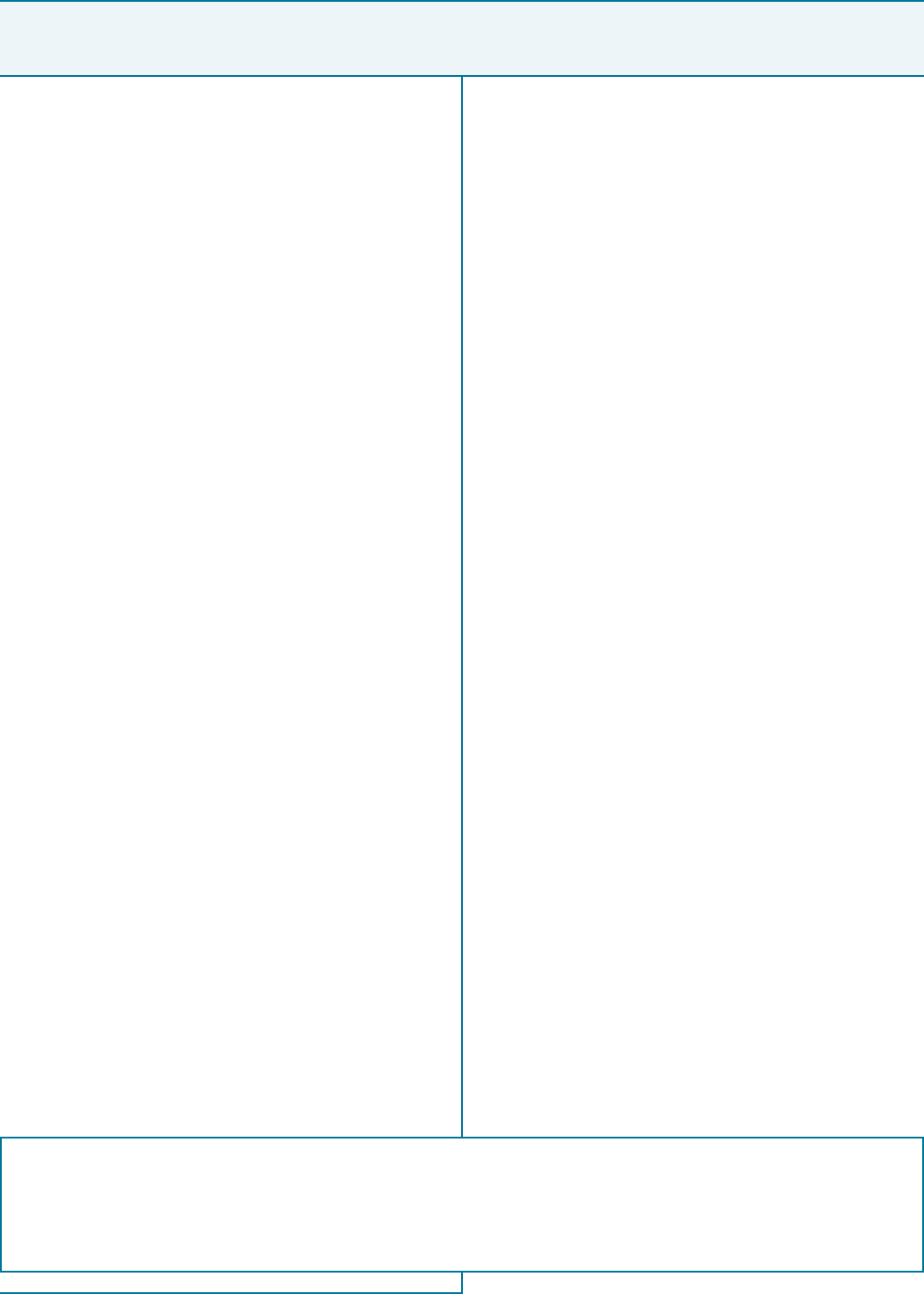

For completeness, Chart 3 plots the enhancements, both

by level and per securitized asset, for non–credit card

enhancements. The only feature of note is the downward trend

in non–credit card enhancements per securitized non–credit

card asset. That finding implies that the upward trend in overall

enhancements per securitized asset evident in Chart 1 results

from the upward trend in credit card enhancements per

securitized asset evident in Chart 2.

Chart 4 breaks out total enhancements into enhancements

of the BHCs’ own securitized assets (“self-enhancements”) and

enhancements provided to third parties (“third-party

enhancements”). Apart from the beginning and the end of the

sample period, self-enhancements were roughly stable at

between $30 billion and $40 billion. By contrast, third-party

enhancements began trending upward in about 2004:Q4 to

reach a peak of about $25 billion in 2008:Q2. Third-party

10

See “Fitch: Chase Increases Credit Enhancement in Credit Card Issuance

Trust (CHAIT),” http://www.reuters.com/article/2009/05/12/

idUS260368+12-May-2009+BW20090512.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 39

Source: Federal Reserve System, Form FR Y-9C, Schedule HC-S.

Chart 3

Non–Credit Card Enhancements

Billions of U.S. dollars Percent

Enhancements as share

of outstanding non–credit

card enhancements

Scale

Total enhancements

Scale

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

0908070605040302

2001

0

5

10

15

20

25

Source: Federal Reserve System, Form FR Y-9C, Schedule HC-S.

Chart 4

Self-Enhancements and Third-Party Enhancements

Billions of U.S. dollars

Third-party

enhancements

Self-enhancements

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

09080706050403022001

enhancements dropped noticeably during the financial crisis,

presumably because BHCs’ own solvency and liquidity came

into question.

While Charts 1-4 tell us something about trends in

enhancements within the banking industry, we were also

interested in how enhancements by bank holding companies

compared with those by financial institutions in the shadow

banking system, namely, insurance companies. Insurance

companies provide enhancements to structured finance

products through guaranties and credit default swaps (CDS).

As there is no central source of data on enhancements provided

by insurance companies, we turned to their 10-K forms for

data. Starting with the nineteen publicly traded insurance

companies, we determined that only six or seven (depending

on the year) provided guaranties for asset-backed securities.

These included firms such as Ambac, MBIA, and Radian.

11

While the companies usually provided a reasonable breakdown

of guarantee coverage—such as residential and consumer loans

and the like—the classifications were not uniform across

companies. Thus, for each company we summed guaranties

across categories and then summed across companies to obtain

the aggregate level of guaranties by publicly traded insurance

companies in a given year.

11

The sample excludes American International Group, Inc. AIG was a

prominent seller of CDS protections on collateralized debt obligations (CDOs)

through one of its subsidiaries, AIG Financial Products. AIG experienced a

severe liquidity crisis due to its rating downgrade in late 2008, and the

subsequent bailout resulted in a substantial decline in outstanding net notional

amount of AIG’s CDS portfolio written on CDO products. Including AIG in

our analysis would therefore cause a more significant downward trend in

insurance companies’ presence in the financial guarantee market for the

sample period. We exclude AIG to make a conservative comparison of the

aggregate volumes of protection provided by banks and insurance firms in the

securitization market.

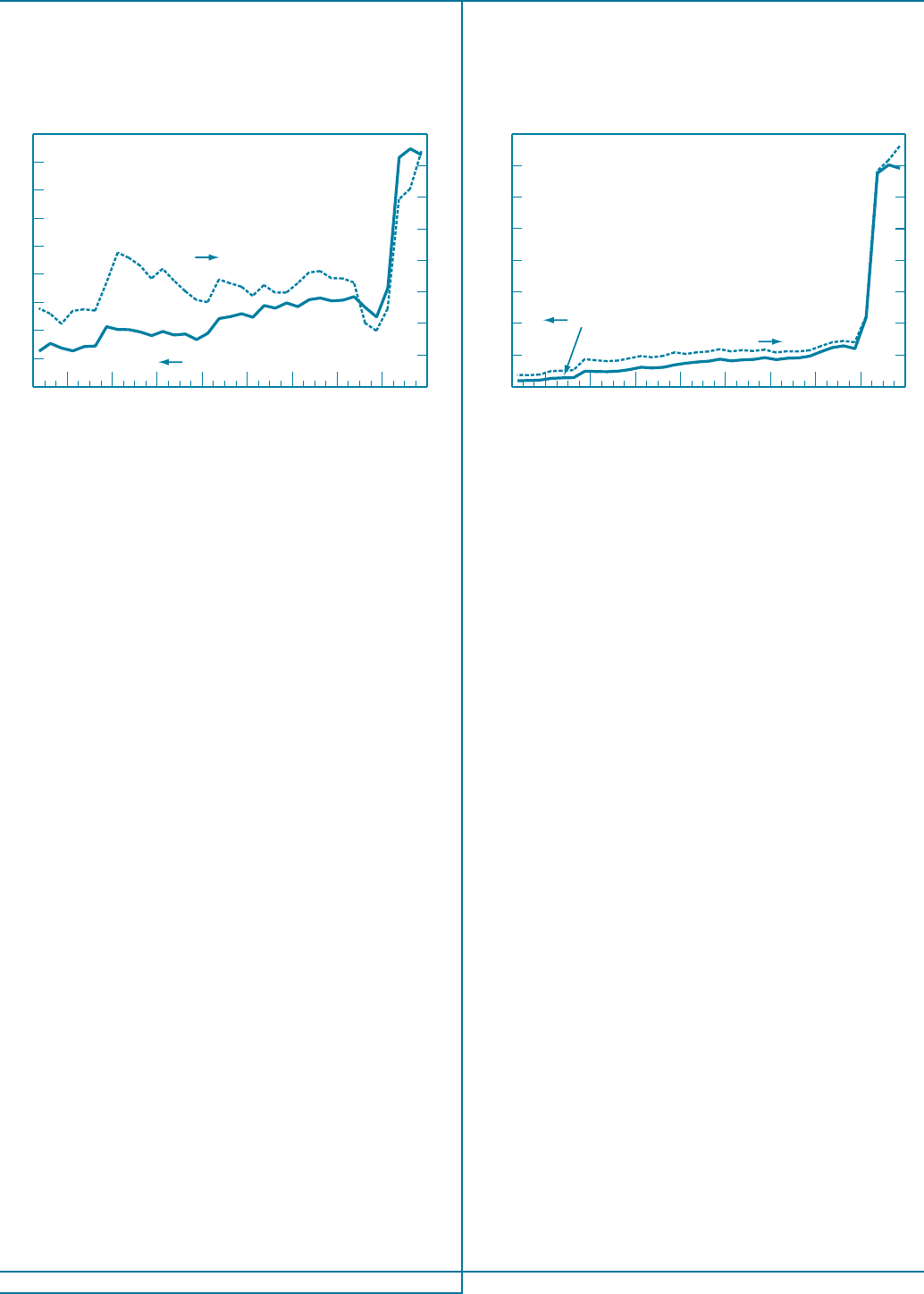

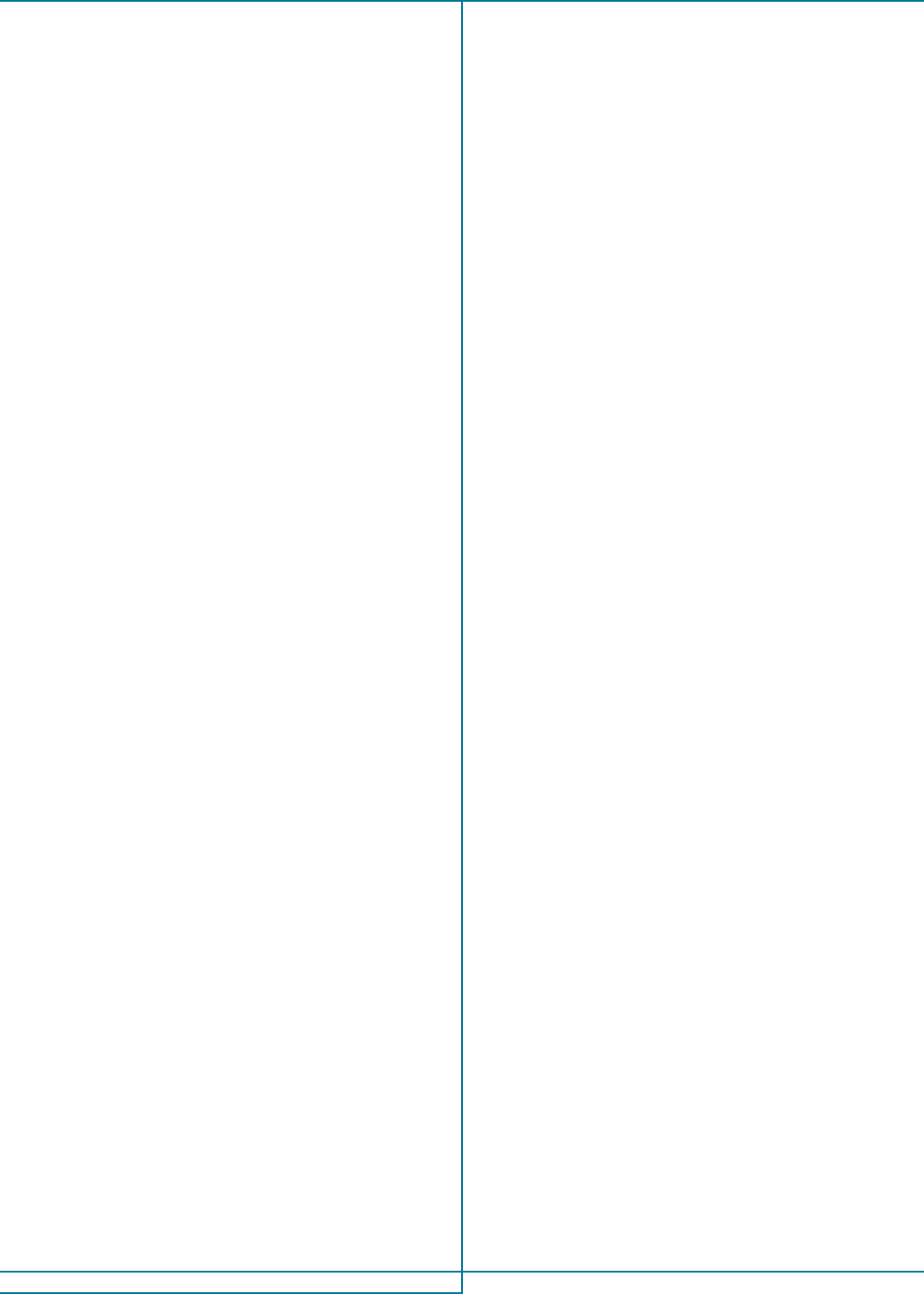

Chart 5 plots the ratio of guaranties by insurance companies

to total enhancements provided by bank holding companies.

The level of guaranties provided by insurance companies

clearly swamps the level of enhancements provided by bank

holding companies; at its peak in 2004:Q4, the ratio was more

than ten to one. However, apart from some notable

fluctuations, including a drop in 2009 because of the increase

in credit card enhancements at JPMC and Bank of America, the

ratio has been fairly trendless, indicating that banks have

maintained (or perhaps increased) their share of the credit

enhancement business.

As noted in the introduction, we found that insurers would

often cite (in their 10-Ks) competition from banks for

enhancement business. Here is another example:

Financial guarantee insurance also competes with other

forms of credit enhancement, including senior-subordinated

structures, credit derivatives, letters of credit and guarantees

(for example, mortgage guarantees where pools of mortgages

secure debt service payments) provided by banks and other

financial institutions, some of which are governmental

agencies. Letters of credit are most often issued for periods

of less than 10 years, although there is no legal restriction

on the issuance of letters of credit having longer terms. Thus,

financial institutions and banks issuing letters of credit

compete directly with our Insurers to guarantee short-term

notes and bonds with a maturity of less than 10 years. To the

extent that banks providing credit enhancement may begin

to issue letters of credit with commitments longer than

10 years, the competitive position of financial guarantee

insurers could be adversely affected (MBIA Inc. 2008,

form 10-K, p. 24).

40 The Role of Bank Credit Enhancements in Securitization

Sources: Federal Reserve System, Form FR Y-9C, Schedule HC-S;

insurance companies’ 10-K forms.

Chart 5

Guaranties to Asset-Backed Securities Provided

by Insurance Companies/Credit Enhancements

Provided by Bank Holding Companies

Ratio

2

4

6

8

10

12

09080706050403022001

3. Panel Regression Results

In this section, we investigate the relationship between the

performance of securitized assets and the extent of credit

enhancements. According to the buffer hypothesis, where

enhancements are a buffer against observable risks, one would

expect a negative relationship between enhancements and

performance. Under the signaling hypothesis, where

enhancements are a signal of unobserved quality, we would

expect a positive relationship between enhancements and

performance.

To investigate that question, we estimate the following

fixed-effect regression models:

(1) Severe Delinquency Rate

it

Total Enhancements

it

Controls .

For each loan category (mortgages, credit card loans, and the

like), the dependent variable is the sum of securitized assets

ninety or more days past due and loans charged off, divided by

total securitized assets outstanding at BHC i in quarter t. The

main independent variable, TotalEnhancements, is the sum of

the three types of credit enhancements discussed earlier scaled

by total outstanding securitizations for each BHC in each

quarter.

12

The controls are unused commitments divided by

total loans in each category, the log of on balance sheet assets,

leverage (total common equity divided by total balance sheet

i

t

++=

+

it

+

assets), ROA (quarterly net income divided by total balance

sheet assets), and risk-weighted assets divided by total balance

sheet assets (a measure of risk). All the variables in this and

subsequent regressions are defined in the appendix. The BHC

and time-fixed (quarter-year) effects control for constant

differences in performance across BHCs and time. We report

Huber-White robust standard errors for all quarter-BHC

observations with nonmissing, nonzero outstanding

securitization. The standard errors are clustered by BHCs. The

equation is estimated from 2001:Q2 to 2007:Q2 , that is, up to

but not including the financial crisis. A BHC is included in the

regression if it had nonzero securitization for a given loan type.

12

Besides the aggregate enhancement, Schedule HC-S reports disaggregated

numbers cross several categories, including retained interest-only strips,

standby letters of credit, subordinated securities, and other enhancements,

as discussed earlier. We focus on the aggregate amount, as discussions with

professionals in this business sector suggest that the overall amount of

enhancements is the most relevant term in the deal-making process.

Table 1

Summary Statistics

Variable Observations Mean

Standard

Deviation

Severe delinquency ratio

a

Residential real estate 3,394 0.006 0.025

Home equity 536 0.012 0.024

Credit card 703 0.012 0.018

Auto 686 0.005 0.011

Other consumer 444 0.027 0.032

Commercial and industrial 717 0.003 0.008

All other 968 0.002 0.008

Total 4,589 0.005 0.017

Total enhancements (ratio)

b

Residential real estate 3,394 0.037 0.150

Home equity 536 0.062 0.108

Credit card 703 0.024 0.071

Auto 686 0.060 0.104

Other consumer 444 0.063 0.095

Commercial and industrial 717 0.037 0.124

All other 968 0.062 0.170

Total 4,589 0.041 0.150

Source: Federal Reserve System, Form FR Y-9C, Schedule HC-S.

a

Severe delinquency ratio = securitized loans ninety days past due plus

charge-offs divided by total loans in that category.

b

Total enhancements = sum of credit-enhancing, interest-only strips

and excess spread accounts, subordinated securities, and other residual

interest; standby letters of credit; and other enhancements divided by

total loans in that category.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 41

Summary statistics are reported in Table 1, and the

regression results are in Table 2. In the regressions, the point

estimates on total enhancements are positive in every loan

category but the residual “all other” and are significantly

different from zero in four of the eight categories: residential

real estate, home equity, auto, and total. Thus, we find no

evidence for the signaling hypothesis and some evidence for

the hypothesis that enhancements serve as a buffer against

observable risk. It is possible that enhancements serve as both

a buffer and a signal but the buffering role dominates.

Although we do not claim that the relationship between

delinquency and enhancements is causal, it is still interesting to

gauge the magnitude of the relationship between the two. To

do so, we calculate how much delinquency rates rise relative to

the average when total enhancements increase by one standard

deviation. Specifically, we calculate the product of the point

estimate for each loan category and the standard deviation

of total enhancements for that category; we then scale that

product by the mean delinquency rate for that category. The

result yields the estimated percentage change in delinquency

(relative to the mean delinquency rate) per standard deviation

change in total enhancements. The results imply a fairly stable

relationship between total enhancements and delinquency

rates in cases where the relationship was statistically significant:

residential real estate (0.43), home equity (0.81), auto (0.56),

and total (0.45).

Table 2

Panel Regression Results

Dependent Variable: Severely Delinquent Loans / Total Securitized Loans

Pre-Crisis (2001:Q2 to 2007:Q2)

Residential

Real Estate

Home

Equity Credit Card Auto

Other

Consumer

Commercial

and Industrial All Other Total

Total enhancements 0.017 0.09 0.044 0.027 0.037 0.003 -0.007 0.015

[2.54]** [4.49]*** [1.07] [2.38]** [1.34] [0.29] [0.86] [2.40]**

Unused commitments -0.083 -0.015 3.714 -0.009 -0.034 -0.004 -0.002 -0.001

[1.85]* [1.22] [1.92]* [1.05] [1.44] 1.05] [0.85] [0.17]

Leverage -0.047 0.015 -0.125 0.001 0.218 0.026 -0.094 -0.04

[1.61] [0.07] [3.35]*** [0.11] [1.18] [0.55] [3.64]*** [1.08]

Return on assets 0.226 -0.11 -0.52 0.011 0.009 0.029 -0.131 -0.042

[1.09] [0.20] [8.58]*** [1.26] [0.03] [0.17] [1.39] [0.49]

Risk-weighted assets/total assets -0.017 0.006 0.01 0.028 -0.003 -0.013 0.002 0.008

[1.75]* [0.20] [0.39] [3.63]*** [0.05] [0.83] [0.24] [0.91]

Log asset size 0.002 0.013 0.009 -0.002 0.022 0.004 -0.002 0.004

[0.92] [1.36] [1.36] [0.88] [1.15] [1.49] [0.71] [1.36]

Observations 3,358 532 703 685 444 706 960 4,543

Number of entities 166 27 34 32 22 35 48 225

R

2

0.04 0.18 0.36 0.2 0.17 0.05 0.06 0.06

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: Robust t-statistics appear in brackets. Time dummies are not reported. Variables are defined in the appendix.

***Statistically significant at the 1 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

42 The Role of Bank Credit Enhancements in Securitization

4. Event Studies: What Do Stock

Price Reactions and Implied

Volatility Tell Us about

the Role of Enhancements?

We next investigate the role of credit enhancements in

securitization by looking at market reactions to the new

disclosure requirement adopted in 2001:Q2 on BHCs’

securitizations. Beginning in that quarter, BHCs started

including in the quarterly “Reports of Condition and Income”

a new schedule that detailed their securitization activities.

The new schedule requires BHCs to disclose comprehensive

information on the volume and performance

13

of seven

categories of securitized assets (the same categories we study

in the panel analysis above). Significantly, BHCs are required

to report the maximum amount of credit exposure they face

through the credit enhancements described above. This new

information first became public after BHCs’ reports for

2001:Q2 were disclosed in August and September 2001. This

event provides a unique opportunity for assessing how banks’

securitization and the associated credit exposure through

enhancements affect shareholders.

We focus on the valuation and risk implications of the newly

disclosed securitization activities. First, we conduct a standard

event study on a sample of 267 BHCs. A one-factor market

model is estimated for each firm using monthly return data

from July 1996 to June 2001, with the S&P 500 index being the

factor. Monthly abnormal returns are calculated for August

and September 2001 and then summed to reach a two-month

cumulative abnormal return (CAR) for each bank.

To see how the newly disclosed securitization activities and

credit enhancements affect valuation, we relate the CARs to

several securitization-related variables through the following

regression:

(2) CAR

i

Securitization

i

Total_Enhancements

i

Total_Enhancements

i

Delinquency

i

Delinquency

i

Unused Commitments

i

Stock Volatility

i

The dependent variable CAR

i

is the two-month cumulative

abnormal return for bank i. All independent variables are

constructed using data from the Federal Reserve Y-9C reports,

which bank holding companies filed as of 2001:Q2 under

the revised reporting rules. Securitization

i

represents the

outstanding principal balance of assets sold and securitized by

bank i, with servicing retained or with recourse or other seller-

provided credit enhancements, and is normalized by the bank’s

total outstanding loans on the balance sheet. This measure

13

The performance metrics include past-due amounts, charge-offs, and

recoveries on assets sold and securitized.

1

+=

2

3

4

5

6

i

reflects the extent to which bank i has moved its loans off the

balance sheet through securitization. Total_Enhancements

i

and Unused Commitments

i

are defined in Section 3 (and the

appendix). While the scale of securitization activities is

captured by Securitization

i

, Total_Enhancements

i

reflects the

extent to which bank i could still be “on the hook” should the

securitized assets perform poorly. We measure performance by

Delinquency

i

, defined as the sum of past-due loan amounts and

year-to-date net charge-offs divided by the total outstanding

securitized assets. Last, to control for a BHC’s risk, we include

the stock volatility estimated using the daily returns in the

252 trading days prior to the disclosure period.

Equation 2 also includes an interaction between

Total_Enhancements

i

and Delinquency

i

. Per our earlier

discussion, we postulated two hypotheses on the role of

enhancements. Under the signaling hypothesis, keeping risk

through enhancements signals bank i’s private knowledge of

good loan quality, implying a positive relationship between

high enhancements and CAR. Under the buffer hypothesis,

banks securitizing riskier collateral need more enhancements

to meet rating agencies’ criteria. In this case, high enhancements

are associated with observably riskier deals, implying a negative

valuation impact. If loan performance is a reasonable proxy

for the observable riskiness of the securitized assets, we expect

the signaling effect to dominate among relatively better-

performing (lower-delinquency) deals, where observable risk

is less a concern, resulting in an overall positive relationship

between Total Enhancements and CAR. When deals are

performing poorly (high delinquency), however, concerns

over “observable risk” would heighten and the buffer role

of enhancements would dominate, leading to a negative

relationship between Total Enhancements and CAR. As a result,

we expect a positive coefficient for Total Enhancements ()

and a negative coefficient for the interaction Total

Enhancements Delinquency ().

Table 3 presents the least-squares regression coefficient

estimates with Huber-White robust standard errors. Each

model estimated includes one of two versions of the

Delinquency

i

variable. Models 1 and 2 use a delinquency

measure based on all past-due loans, while models 3 and 4

use one that includes severe delinquencies only. The cross-

section variation of the CARs appears to be significantly

associated with the securitization-related variables. The

impact of Securitization is significantly positive in all

specifications, suggesting that more favorable market

reactions are associated with larger-scale securitizations as

first disclosed by banks in 2001. This finding is consistent

with the notion that securitization transactions were

generally viewed as positive-NPV (that is, profitable)

projects in 2001 and that the market reacted more favorably

2

3

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 43

when banks reported that a higher portion of their assets

was being securitized.

In columns 1 and 3 of Table 3, Total_Enhancements,

Delinquency, Unused Commitments, and Stock Volatility are all

statistically insignificant. Securitization is the only significant

variable in those models.

Models 2 and 4 suggest that the insignificance of Total

Enhancements in models 1 and 3 is likely due to the omitted

interaction between enhancements and loan performance. In

both models 2 and 4, Total Enhancements alone is significantly

positive and has a strongly negative interaction effect with loan

performance, Total Enhancements Delinquency. A simple

numerical exercise further illustrates the importance of the

interplay between enhancement and loan performance in

determining which of the two hypotheses dominates. Using

model 4 as an example, we can compare the relationship

between the market reaction (CAR) and enhancements at

different levels of severe loan delinquencies off the balance

sheet. For example, with no severe delinquency (Delinquency =

0 percent), the overall effect of Total Enhancements is

0.168 + (-15.567) 0 = 0.168, a positive wealth effect of

enhancements consistent with the signaling hypothesis.

As the severe delinquency ratio rises, however, the effect of

Total Enhancements weakens monotonically but remains

positive until severe delinquency reaches 0.168/15.567 =

1.08 percent.

14

Once the delinquency rate exceeds

1.08 percent, the net effect of Total Enhancements on CAR

becomes increasingly negative as delinquency further rises.

For example, when severe delinquency is 1.18 percent,

15

the net effect of Total Enhancements on CAR becomes

0.168 + (-15.567) 1.18 percent = -1.6 percent. This negative

relationship is consistent with the notion that investors

become increasingly concerned when a bank with poorly

performing securitized assets discloses a high level of credit

enhancements, just as the buffer hypothesis would predict.

We next focus on the risk implications of banks’

securitization activities. Specifically, we examine changes in

option-implied volatilities around the event period. For

fifty-one banks in our sample, we obtained data from the

OptionMetrics Ivy database, which features implied volatilities

calculated using the Cox, Ross, and Rubinstein (1979)

binomial model adjusted for dividends. Because some banks

have numerous exchange-traded options, we impose a number

of widely used sample restrictions.

16

We calculate weighted-

average implied volatilities at the firm level, using each option’s

vega as the weight (Latané and Rendleman 1976). We then run

the following regression:

(3) [log (implied_vol

i

)]

Securitization

i

+ Total_Enhancements

i

+ Total_Enhancements

i

Delinquency

i

Delinquency

i

Unused Commitments

i

Stock Volatility

i

14

This number corresponds to the 90th percentile of the severe delinquency

ratio in our sample.

15

This number corresponds to the 92nd percentile of the severe delinquency

ratio in our sample.

16

Specifically, several studies (see, for example, Patell and Wolfson [1981])

report that implied volatility estimates behave erratically during the last two

to four weeks before expiration and also that options with a very long time to

expiration are less sensitive to volatility changes). We therefore study only

those options with expiration dates between 28 and 100 days away from the

event day, with the latter criterion due to Deng and Julio (2005). Last, we

require each option to have nonzero trading volume in the event window.

1

+=

2

3

4

5

6

i

Table 3

Regression Analysis of Cumulative Abnormal

Equity Returns

Dependent Variable: Cumulative Abnormal Equity Returns,

August 2001-September 2001

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Constant -0.002 -0.0034 -0.0016 -0.0027

[0.34] [0.57] [0.28] [0.0059]

Securitization 0.04 0.032 0.042 0.036

[3.48]*** [2.62]*** [3.88]*** [2.99]***

Total enhancements 0.047 0.295 0.06 0.168

[0.58] [4.40]*** [0.82] [3.45]***

Delinquencies (all) -0.106 0.499

[0.46] [1.59]

Delinquencies (all)

total enhancements

-10.933

[3.06]***

Delinquencies

(severe)

-0.337

[0.78]

0.759

[1.50]

Delinquencies

(severe) total

enhancements

-15.567

[3.32]***

Unused commitments 0.014 -0.122 0.005 -0.041

[0.20] [2.31]** [0.08] [0.83]

Stock volatility -1.498 -1.33 -1.496 -1.374

[1.53] [1.36] [1.53] [1.41]

Observations 267 267 267 267

R

2

(percent) 5757

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: Robust t-statistics appear in brackets. Variables are defined

in the appendix.

***Statistically significant at the 1 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

44 The Role of Bank Credit Enhancements in Securitization

The dependent variable [log(implied_vol

i

)] measures the

change in log(implied_vol

i

) from the beginning of August 2001

to the end of September 2001. All the independent variables

remain the same as in equation 2.

17

Overall, the significantly positive coefficient estimates for

Securitization suggest that higher securitization activities are

associated with higher risk as perceived in the forward-looking

option market (Table 4). This result, coupled with the positive

valuation effect of securitization just noted, suggests that

securitization was generally viewed as increasing both

shareholder value and risk. Unused commitments were also

17

We cannot control for market movement in the current regression setup.

As an alternative, we define excess implied volatility as the difference between

each option’s implied volatility and market volatility and use it to calculate the

dependent variable. The results are quantitatively similar to those in Table 4.

associated with higher risk, despite the lack of valuation

effect (see Table 2). Total Enhancements are always positive

and significant, which is sensible given that enhancements

represent exposure to the securitizing bank. Unlike the analysis

of valuation impact, we do not observe any significant

interaction effect between Total Enhancements and

Delinquency in the risk effect of credit enhancements. Overall,

the evidence suggests that both securitization activities and the

associated credit enhancements are perceived to add risk to the

securitizing bank, even though underlying assets have been

moved off the balance sheet.

5.Conclusion

This article focuses on credit enhancements provided by banks

in the U.S. securitization market. Contrary to the impression

that banks have been surpassed by other financial institutions

in the shadow banking system, we show that banks have held

their own relative to monoline insurance companies in the

business of providing credit enhancements.

Having shown that banks are still important in providing

enhancements, we also investigate the role of bank enhance-

ments in the securitization process. Enhancements obviously

serve as a buffer against observable risk, but we are interested

in the hypothesis, commonly advanced by academics, that

enhancements also serve as a signal of unobservable quality.

By keeping “skin in the game,” banks offering enhancements

may signal to investors or raters that the assets being securitized

are of high quality.

Our event study of banks’ first-time disclosure in 2001 of

their securitization activities finds evidence that the buffer

effect and the signal hypothesis could both be at play, with the

dominant effect depending on the riskiness of the securitized

assets. Specifically, we find that stock prices reacted favorably

to high enhancement provisioning among banks with better-

performing (lower-delinquency) securitizations, consistent

with the signaling hypothesis. Among banks with poorly

performing securitizations (high delinquency), however, stock

prices reacted negatively to higher levels of enhancements,

suggesting that the buffer role of enhancements dominates

under observably risky securitizations.

Evidence from cross-sectional regressions favors the buffer

hypothesis of enhancements. There we find a positive

relationship between delinquency rates on banks’ securitized

assets and credit enhancements, contrary to what the signaling

hypothesis suggests. Of course, it could be that enhancements

do serve a signaling role, but that role is dwarfed by the

buffering role.

Table 4

Regression Analysis of Changes in Implied Volatility

Dependent Variable: [log( Implied Volatility )]

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Constant 0.414 0.404 0.418 0.41

[5.12]*** [4.95]*** [5.37]*** [5.25]***

Securitization 0.045 0.043 0.049 0.047

[2.21]** [1.80]* [2.39]** [2.12]**

Total enhancements 0.279 0.367 0.289 0.316

[2.64]** [2.06]** [2.62]** [2.64]**

Delinquencies (all) -0.137 0.15

[0.27] [0.15]

Delinquencies (all)

total enhancements

-4.744

[0.44]

Delinquencies (severe) -0.538 -0.125

[0.71] [0.08]

Delinquencies (severe)

total enhancements

-5.53

[0.38]

Unused commitments 0.187 0.145 0.177 0.172

[2.32]** [1.53] [2.10]** [1.92]*

One-year lagging

daily stock return

standard deviation

-10.945

[3.46]***

-10.626

[3.39]***

-10.952

[3.55]***

-10.726

[3.48]***

Observations 52 52 52 52

R

2

(percent) 29303030

Source: Authors’ calculations.

Notes: Robust t-statistics appear in brackets. Variables are defined

in the appendix.

***Statistically significant at the 1 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 5 percent level.

***Statistically significant at the 10 percent level.

FRBNY Economic Policy Review / July 2012 45

Delinquencies (All): Securitized loans thirty or more days past

due plus charge-offs divided by total securitized loans in the

category.

Delinquencies (All) (Total Enhancements): Delinquencies

(all) times total credit enhancements.

Delinquencies (Severe): Securitized loans ninety days past due

plus charge-offs divided by total securitized loans in the

category.

Delinquencies (Severe) (Total Enhancements): Delinquencies

(severe) times total credit enhancements.

Leverage: Total common equity divided by total balance sheet

assets.

Log Asset Size: Natural log of total balance sheet assets.

Risk-Weighted Assets/Total Assets: Total risk-weighted assets

divided by total balance sheet assets.

ROA: Quarterly net income divided by total balance sheet

assets.

Securitization: Total securitized loans divided by total balance

sheet loans.

Severely Delinquent Loans/Total Securitized Loans: Securitized

loans ninety days past due plus charge-offs divided by total

securitized loans in the category.

Stock Volatility: One-year lagging daily stock return standard

deviation.

Total (Credit) Enhancements: Sum of interest-only strips,

subordinated securities, and other residual interest; standby

letters of credit; and other enhancements divided by total loans

in the category.

Unused Commitments: Unused commitments to provide

liquidity divided by total loans in the category.

Appendix: Variable Definitions

References

46 The Role of Bank Credit Enhancements in Securitization

Albertazzi, U., G. Eramo, L. Gambacorta, and C. Salleo. 2011.

“Securitization Is Not that Evil after All.” BIS Working Paper

no. 341, March.

Ashcraft, A. B., and T. Schuermann. 2008. “Understanding the

Securitization of Subprime Mortgage Credit.” Federal Reserve

Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 318, March.

Ashcraft, A. B., J. Vickery, and P. Goldsmith-Pinkham. 2010. “MBS

Ratings and the Mortgage Credit Boom.” Federal Reserve Bank

of New York Staff Reports, no. 449, May.

Berger, A. N., and G. F. Udell. 1990. “Collateral, Loan Quality, and

Bank Risk.” Journal of Monetary Economics 25, no. 1

(January): 21-42.

Bernanke, B. S. 2012. “Some Reflections on the Crisis and the Policy

Response.” Remarks delivered at the Russell Sage Foundation

and Century Foundation Conference on “Rethinking Finance,”

New York City, April 13.

Besanko, D., and A. Thakor. 1987. “Collateral and Rationing: Sorting

Equilibria in Monopolistic and Competitive Credit Markets.”

International Economic Review 28, no. 3 (October): 671-89.

Cetorelli, N., and S. Peristiani. 2012. “The Role of Banks in Asset

Securitization.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Economic

Policy Review 18, no. 2 (July): 47-63.

Chan, Y., and G. Kanatas. 1985. “Asymmetric Valuations and the Role

of Collateral in Loan Agreements.” Journal of Money, Credit,

and Banking 17, no. 1 (February): 84-95.

Cox, J. C., S. A. Ross, and M. Rubinstein. 1979. “Option Pricing:

A Simplified Approach.” Journal of Financial Economics 7,

no. 3 (September): 229-63.

Deng, Q., and B. Julio. 2005. “The Informational Content of Implied

Volatility around Stock Splits.” University of Illinois at

Urbana-Champaign working paper, September.

Downing, C., D. Jaffee, and N. Wallace. 2009. “Is the Market for

Mortgage-Backed Securities a Market for Lemons?” Review

of Financial Studies 22, no. 7 (July): 2457-94.

Erel, I., T. D. Nadauld, and R. M. Stulz. 2011. “Why Did U.S. Banks

Invest in Highly Rated Securitization Tranches?” Fisher College

of Business Working Paper no. 2011-03-016, July 25.

James, C. M. 2010. “Mortgage-Backed Securities: How Important Is

‘Skin in the Game’?” Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco

Economic Letter, no. 2010-37, December 13.

Latané, H. A., and R. J. Rendleman, Jr. 1976. “Standard Deviations

of Stock Price Ratios Implied in Option Prices.” Journal

of Finance 31, no. 2 (May): 369-81.

Levitin, A. J. 2011. “Skin in the Game: Risk Retention Lessons from

Credit Card Securitization.” Georgetown Law and Economics

Research Paper no. 11-18, August 9.

Patell, J. M., and M. A. Wolfson. 1981. “The Ex Ante and Ex Post Price

Effects of Quarterly Earnings Announcements Reflected in Option

and Stock Prices.” Journal of Accounting Research 19, no. 2

(autumn): 434-58.

Pozsar, Z., T. Adrian, A. Ashcraft, and H. Boesky. 2010. “Shadow

Banking.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports,

no. 458, July.

Standard and Poor’s. 2008. “The Basics of Credit Enhancement

in Securitizations.” June 24.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York

or the Federal Reserve System. The Federal Reserve Bank of New York provides no warranty, express or implied, as to the

accuracy, timeliness, completeness, merchantability, or fitness for any particular purpose of any information contained in

documents produced and provided by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York in any form or manner whatsoever.